Engineering:Veena

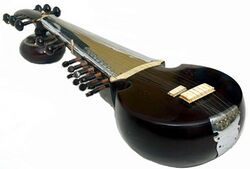

A Saraswati Veena | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Vina[1] |

| Classification | String instruments |

| Developed | Veena has applied to stringed instruments in Indian written records since at least 1000 BCE. Instruments using the name have included forms of arched harp and musical bow, lutes, medieval stick zithers and tube zithers, bowed chordophones, fretless lutes, the Hindustani bīn and Sarasvati veena.[2] |

| Related instruments | |

| Chitra veena, Harp-style veena, Mohan veena, Rudra veena, Saraswati veena, Vichitra veena, Sarod, Sitar, Surbahar, Sursingar, Tambouras, Tambura, | |

The veena, also spelled vina (Sanskrit: वीणा IAST: vīṇā), is any of various chordophone instruments from the Indian subcontinent.[3] Ancient musical instruments evolved into many variations, such as lutes, zithers and arched harps.[1] The many regional designs have different names such as the Rudra veena, the Saraswati veena, the Vichitra veena and others.[4][5]

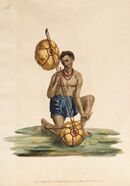

The North Indian rudra veena, used in Hindustani classical music, is a stick zither.[1] About 3.5 to 4 feet (1 to 1.2 meters) long to fit the measurements of the musician, it has a hollow body and two large resonating gourds under each end.[5] It has four main strings which are melodic, and three auxiliary drone strings.[1] To play, the musician plucks the melody strings downward with a plectrum worn on the first and second fingers, while the drone strings are strummed with the little finger of the playing hand. The musician stops the resonating strings, when so desired, with the fingers of the free hand. In modern times the veena has been generally replaced with the sitar in North Indian performances.[1][3]

The South Indian Saraswati veena, used in Carnatic classical music, is a lute. It is a long-necked, pear-shaped lute, but instead of the lower gourd of the North Indian design, it has a pear-shaped wooden piece. However it, too, has 24 frets, four melody strings, and three drone strings, and is played similarly. It remains an important and popular string instrument in classical Carnatic music.[1][6][7]

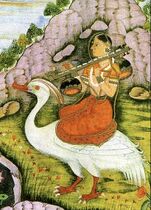

As a fretted, plucked lute, the veena can produce pitches in a full three-octave range.[3] The long, hollow neck design of these Indian instruments allow portamento effects and legato ornaments found in Indian ragas.[7] It has been a popular instrument in Indian classical music, and one revered in the Indian culture by its inclusion in the iconography of Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of arts and learning.[6]

File:Kiravani-L Ramakrishnan.ogg File:Shri Nilotpala Nayike, rendered on the Veena by L Ramakishnan.ogg

Etymology and history

- See: Ancient veena :See: History of lute-family instruments

The Sanskrit word veena (वीणा) in ancient and medieval Indian literature is a generic term for plucked string musical instruments. It is mentioned in the Rigveda, Samaveda and other Vedic literature such as the Shatapatha Brahmana and Taittiriya Samhita.[9][10] In the ancient texts, Narada is credited with inventing the Tampura, and is described as a seven-string instrument with frets.[9][11] According to Suneera Kasliwal, a professor of music, in the ancient texts such as the Rigveda and Atharvaveda (both pre-1000 BCE), as well as the Upanishads (c. 800–300 BCE), a string instrument is called vana, a term that evolved to become veena. The early Sanskrit texts call any stringed instrument vana; these include bowed, plucked, one string, many strings, fretted, non-fretted, zither, lute or harp lyre-style string instruments.[12][13][14]

A person who plays a veena is called a vainika.[16]

The Natya Shastra by Bharata Muni, the oldest surviving ancient Hindu text on classical music and performance arts, discusses the veena.[17] This Sanskrit text, probably complete between 200 BCE and 200 CE,[18] begins its discussion by stating that "the human throat is a sareer veena, or a body's musical string instrument" when it is perfected, and that the source of gandharva music is such a throat, a string instrument and flute.[17] The same metaphor of human voice organ being a form of veena, is also found in more ancient texts of Hinduism, such as in verse 3.2.5 of the Aitareya Aranyaka, verse 8.9 of the Shankhayana Aranyaka and others.[10][14][19] The ancient epic Mahabharata describes the sage Narada as a Vedic sage famed as a "vina player".[20]

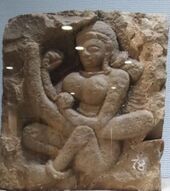

The Natya Shastra describes a seven-string instrument and other string instruments in 35 verses,[21] and then explains how the instrument should be played.[11][22] The technique of performance suggests that the veena in Bharata Muni's time was quite different than the zither or the lute that became popular after the Natya Shastra was complete. The ancient veena, according to Allyn Miner and other scholars, was closer to an arched harp. The earliest lute and zither style veena playing musicians are evidenced in Hindu and Buddhist cave temple reliefs in the early centuries of the common era. Similarly, Indian sculptures from the mid-1st millennium CE depict musicians playing string instruments.[11] By about the 6th century CE, the goddess Saraswati sculptures are predominantly with veena of the zither-style, similar to modern styles.[23]

The early Gupta veena: depiction and playing technique

One of the early veenas used in India from early times until the Gupta period was an instrument of the harp type, and more precisely of the arched harp. It was played with the strings kept parallel to the body of the player, with both hands plucking the strings, as shown on Samudragupta's gold coins.[24] The Veena Cave at Udayagiri has one of the earliest visual depictions of a veena player, considered to be Samudragupta.

Construction

At a first glance, the difference between the North and South Indian design is the presence of two resonant gourds in the North, while in the South, instead of the lower gourd there is a pear-shaped wooden body attached. However, there are other differences, and many similarities.[1] Modern designs use fiberglass or other materials instead of hollowed jackwood and gourds.[25] The construction is personalized to the musician's body proportions so that she can hold and play it comfortably. It ranges from about 3.5 to 4 feet (1 to 1.2 meters). The body is made of special wood and is hollow. Both designs have four melody strings, three drone strings and twenty-four frets.[1][3][5] The instrument's end is generally tastefully shaped such as a swan and the external surfaces colorfully decorated with traditional Indian designs.[25]

The melody strings are tuned in c' g c G (the tonic, the fifth, the octave and the fourth[26]), from which sarani (chanterelle) is frequently used.[7] The drone strings are tuned in c" g' c' (the double octave, the tonic and the octave[26]). The drones are typically used to create rhythmic tanams of Indian classical music and to express harmony with clapped tala of the piece.[7]

The main string is called Nāyakī Tār (नायकी तार), and in the Sarasvati veena it is on the onlooked's left side.[27] The instrument is played with three fingers of the right (dominant) hand, struck inwards or outwards with a bent-wire plectrum (a "mizrab"). The index and second fingers strike inwards on the melody string, alternating between notes, and the little finger strikes outward on the sympathetic strings.

The bola alphabets struck in the North Indian veena are da, ga, ra on the main strings, and many others by a combination of fingers and other strings.[28][29] The veena settings and tuning may be fixed or adjusted by loosening the pegs, to perform Dhruva from fixed and Cala with loosened pegs such that the second string and first string coincide.[30]

One of the earliest description of the terminology currently used for veena construction, modification and operation appears in Sangita Cudamani by Govinda.[31]

Types

thumb |200px|Mayuri veena, 1903

Being a generic name for any string instrument, there are numerous types of veena.[32] Some significant ones are:

- Rudra veena is a fretted veena, with two large equal size tumba (resonators) below a stick zither.[33] This instrument is played by laying it slanting with one gourd on a knee and other above the shoulder.[26][34] The mythology states that this instrument was created by god Shiva[33] It may be a post-6th century medieval era invention.[34] According to Alain Daniélou, this instrument is more ancient, and its older known versions from 6th to 10th century had just one resonator with the seven strings made from different metals.[26]

- Saraswati veena is another fretted veena, and one highly revered in Indian traditions, particularly Hinduism. This is often pictured, shown as two resonators of different size. Previously known as Raghunatha veena, during the period of King Raghunatha Nayaka. This is played by holding it at about a 45 degree angle across one's body, and the smaller gourd over the musician's left thigh. This instrument is related to an ancient instrument of South India, around the region now called Kerala, where the ancient version is called Nanthuni or Nanduruni.[35]

- Vichitra veena and Chitra veena or gottuvadhyam do not have frets. It sounds close to humming human singer. The Vichitra veena is played with a piece of ovoid or round glass, which is used to stop the strings to create delicate musical ornaments and slides during a performance.[33]

- Sitar is a Persian word meaning three strings.[36] Legends state that Amir Khusro of Delhi Sultanate renamed the Tritantri veena to sitar, but this is unlikely because the list of musical instruments created by Akbar historians makes no mention of sitar or sitariya.[37] The sitar has been popular with Indian Muslim musicians.[38]

- Surbahar the base tuned version of the Sitar, created due to the fact that Sitar players wanted to play a base tune like that of the Saraswati veena.

- Ālāpiṇī vīṇā. Historical. A one string stick-zither style veena, shorter than the one string Eka-tantri vina. It had one half-gourd resonator, which was pressed into the player's chest while plucking the string.

- Bobbili Veena, a specialized Saraswati veena, carved from a single piece of wood. Named for Bobbili in Andhra Pradesh, where the instrument originated.

- Chitra veena, a modern 21-string fretless lute, also called Gottuvadhyam or Kotuvadya.

- Chitra veena, a 7-string arched harp, mainstream from ancient times until about the 5th century CE.

- Kachapi veena, now called Kachua sitar, built with a wooden model of a turtle or tortoise as a resonator.[36]

- Kinnari veena, one of three veena types mentioned in the Sangita Ratnakara (written 1210–1247 CE) by Śārṅgadeva. The other two mentioned were the Ālāpiṇī vīṇā and the Eka-tantri vina. Tube zither with multiple gourds for resonators.[2] In surviving museum examples, the center gourd is open where it presses against the player's chest, like the Kse diev or Ālāpiṇī vīṇā.

- Pinaki veena, related to Sarangi.[39] Historical. A bowed Veena, resembling the rudra veena. The notes were picked by moving a stick or coconut shell along the string.

- Pulluva veena, used by the Pulluvan tribe of Kerala in religious ceremonies and Pulluvan pāttu.

- Mattakokila vīṇā (meaning "intoxicated cuckoo"), a 21-string instrument, mentioned in literature, type unproven. Possibly an ancient veena (arched harp) or a board zither.[2][40][41]

- Mohan veena, A modified sarod, created by sarod player Radhika Mohan Maitra in the 1940s. Made out of a modified Hawaiian guitar and a sarod.

- Mayuri veena, Also called Taus (derived from Arabic tawwus meaning, peacock), an instrument with the carving of a peacock as a resonator, decorated with genuine peacock feathers.

- Mukha veena, A blowing instrument.

- Naga veena, An instrument with the carving of a snake for decoration.

- Nagula veena, An instrument with no resonator.

- Shatatantri veena (Santoor),

- Gayatri veena (with one string only)

- Saptatantri veena

- Ranjan veena

- Sagar veena, a Pakistani instrument, created in 1970 by prominent Pakistani lawyer Raza Kazim.

- Saradiya veena, now called Sarod.[42]

- Thanjavur veena, a specialized Saraswati veena, carved from a single piece of wood. Named for Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu, where the instrument originated.

- Triveni veena

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Vina: Musical Instrument, Encyclopædia Britannica (2010)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Alastair Dick; Gordon Geekie; Richard Widdess (1984). Sadie, Stanley. ed. The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. pp. 729–730. Volume 3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Dorothea E. Hast; James R. Cowdery; Stanley Arnold Scott (1999). Exploring the World of Music: An Introduction to Music from a World Music Perspective. Kendall & Hunt. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-7872-7154-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=00CwGRwv6XQC&pg=PA151.

- ↑ Tutut Herawan; Rozaida Ghazali; Mustafa Mat Deris (2014). Recent Advances on Soft Computing and Data Mining. Springer. p. 512. ISBN 978-3-319-07692-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=VdYlBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA512.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Ritwik Sanyal; Richard Widdess (2004). Dhrupad: Tradition and Performance in Indian Music. Ashgate. pp. 23–25. ISBN 978-0-7546-0379-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=7o8HAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lochtefeld 2002, pp. 753–754.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Randel 2003, pp. 819–820.

- ↑ Subramanian Swaminathan. "Paintings". https://www.saigan.com/heritage/painting/ajanta/ajanta15.html. "Kinnara playing Kachchapa Vina, Padmapani Panel, Cave 1"

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Monier Monier-Williams, वीणा, Sanskrit-English Dictionary with Etymology, Oxford University Press, page 1005

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Rowell 2015, pp. 33, 86–87, 115–116.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Allyn Miner (2004). Sitar and Sarod in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-81-208-1493-6. https://archive.org/details/sitarsarodin18th00mine.

- ↑ Suneera Kasliwal (2004). Classical musical instruments. Rupa. pp. 70–72, 102–114. ISBN 978-81-291-0425-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=GVsUAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Te Nijenhuis 1974, pp. 17–22.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Beck 1993, pp. 108–112.

- ↑ லலிதாராம் (translation from Tamil: Lalitaram) (February 15 – March 14, 2005). "யாழ் என்னும் இசைக்கருவி - ஒரு பார்வை (translation from Tamil: Jaffna Musical Instrument - A View)". Varalaaru.com (8). http://www.varalaaru.com/design/article.aspx?ArticleID=109.

- ↑ Gabe Hiemstra (22 February 2019). "Vainika, Vaiṇika: 6 definitions". https://www.wisdomlib.org/definition/vainika. "Cologne Digital Sanskrit Dictionaries: Benfey Sanskrit-English Dictionary...Vaiṇika (वैणिक).—i. e. vīṇā + ika, m. A lutist."

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 A Madhavan (2016). Siyuan Liu. ed. Routledge Handbook of Asian Theatre. Routledge. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-1-317-27886-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=H1iFCwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Lidova 2014.

- ↑ Bettina Bäumer; Kapila Vatsyayan (1988). Kalatattvakosa: A Lexicon of Fundamental Concepts of the Indian Arts. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-81-208-1402-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=uPoIZaGGtiMC&pg=PA135.

- ↑ Dalal 2014, pp. 272–273.

- ↑ Rowell 2015, pp. 114–116.

- ↑ Rowell 2015, pp. 98–104.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Catherine Ludvík (2007). Sarasvatī, Riverine Goddess of Knowledge: From the Manuscript-carrying Vīṇā-player to the Weapon-wielding Defender of the Dharma. BRILL Academic. pp. 227–229. ISBN 978-90-04-15814-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=4lsYKIXBOK0C&pg=PA227.

- ↑ ""The Coin Galleries: Gupta: Samudragupta"". http://coinindia.com/galleries-samudragupta.html.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Nettl et al. 1998, pp. 352–355.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Rudra Veena, Alain Danielou, Smithsonian Folkways and UNESCO (1987)

- ↑ Caudhurī 2000, p. 79.

- ↑ Caudhurī 2000, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Rowell 2015, pp. 153–164.

- ↑ Caudhurī 2000, pp. 111–113.

- ↑ Gautam 1993, p. 9.

- ↑ Martinez 2001, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Sorrell & Narayan 1980, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Suneera Kasliwal (2004). Classical musical instruments. Rupa. pp. 116–124. ISBN 978-81-291-0425-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=GVsUAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Suneera Kasliwal (2004). Classical musical instruments. Rupa. pp. 117–118, 123. ISBN 978-81-291-0425-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=GVsUAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Caudhurī 2000, p. 179.

- ↑ Caudhurī 2000, p. 65.

- ↑ Caudhurī 2000, p. 66.

- ↑ Caudhurī 2000, p. 177.

- ↑ Sadie, Stanley, ed (1984). The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. p. 623. Volume 2.

- ↑ Sadie, Stanley, ed (1984). The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. p. 477. Volume 3. "in...Sangītaratnākara, a chordophone with 21 strings...is mentioned...does not make it clear whether this was a board zither or even whether the author had actually seen one...may have been a...harp-vīnā...".

- ↑ Caudhurī 2000, p. 176.

Bibliography

- Beck, Guy (1993). Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-87249-855-6.

- Caudhurī, Vimalakānta Rôya (2000). The Dictionary of Hindustani Classical Music. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1708-1. https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofhind00roya.

- Dalal, Roshen (2014). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-81-8475-277-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=zrk0AwAAQBAJ.

- Daniélou, Alain (1949). Northern Indian Music, Volume 1. Theory & technique; Volume 2. The main rāgǎs. London: C. Johnson. OCLC 851080.

- Gautam, M.R. (1993). Evolution of Raga and Tala in Indian Music. Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 81-215-0442-2.

- Kaufmann, Walter (1968). The Ragas of North India. Oxford & Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34780-0. OCLC 11369. https://archive.org/details/ragasofnorthindi00kauf.

- Lal, Ananda (2004). The Oxford Companion to Indian Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-564446-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=DftkAAAAMAAJ.

- Lidova, Natalia (2014). Natyashastra. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780195399318-0071.

- Lochtefeld, James G. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, 2 Volume Set. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-2287-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=5kl0DYIjUPgC.

- Martinez, José Luiz (2001). Semiosis in Hindustani Music. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1801-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=OwJRnFIcM4cC.

- Nettl, Bruno; Ruth M. Stone; James Porter; Timothy Rice (1998), The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia : the Indian subcontinent, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-8240-4946-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=ZOlNv8MAXIEC

- Randel, Don Michael (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music (fourth ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01163-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=02rFSecPhEsC.

- Rowell, Lewis (2015). Music and Musical Thought in Early India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73034-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=h5_UCgAAQBAJ.

- Sorrell, Neil; Narayan, Ram (1980). Indian Music in Performance: A Practical Introduction. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-0756-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=jNhRAQAAIAAJ.

- Te Nijenhuis, Emmie (1974). Indian Music: History and Structure. BRILL Academic. ISBN 90-04-03978-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=NrgfAAAAIAAJ.

- Vatsyayan, Kapila (1977). Classical Indian dance in literature and the arts. Sangeet Natak Akademi. OCLC 233639306., Table of Contents

- Vatsyayan, Kapila (2008). Aesthetic theories and forms in Indian tradition. Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 978-81-87586-35-7. OCLC 286469807.

- Wilke, Annette; Moebus, Oliver (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=9wmYz_OtZ_gC.

External links

- Rudra Veena, Vichitra Veena, Sarod and Shahnai, Alain Danielou, Smithsonian Folkways and UNESCO

- Music of India Ensemble: Veena, Department of Ethnomusicology, UCLA

|