Finance:Complementary good

In economics, a complementary good is a good whose appeal increases with the popularity of its complement. Technically, it displays a negative cross elasticity of demand and that demand for it increases when the price of another good decreases.[1] If is a complement to , an increase in the price of will result in a negative movement along the demand curve of and cause the demand curve for to shift inward; less of each good will be demanded. Conversely, a decrease in the price of will result in a positive movement along the demand curve of and cause the demand curve of to shift outward; more of each good will be demanded. This is in contrast to a substitute good, whose demand decreases when its substitute's price decreases.[2]

When two goods are complements, they experience joint demand - the demand of one good is linked to the demand for another good. Therefore, if a higher quantity is demanded of one good, a higher quantity will also be demanded of the other, and vice versa. For example, the demand for razor blades may depend on the number of razors in use; this is why razors have sometimes been sold as loss leaders, to increase demand for the associated blades.[3] Another example is that sometimes a toothbrush is packaged free with toothpaste. The toothbrush is a complement to the toothpaste; the cost of producing a toothbrush may be higher than toothpaste, but its sales depends on the demand of toothpaste.

All non-complementary goods can be considered substitutes.[4] If and are rough complements in an everyday sense, then consumers are willing to pay more for each marginal unit of good as they accumulate more . The opposite is true for substitutes: the consumer is willing to pay less for each marginal unit of good "" as it accumulates more of good "".

Complementarity may be driven by psychological processes in which the consumption of one good (e.g., cola) stimulates demand for its complements (e.g., a cheeseburger). Consumption of a food or beverage activates a goal to consume its complements: foods that consumers believe would taste better together. Drinking cola increases consumers' willingness to pay for a cheeseburger. This effect appears to be contingent on consumer perceptions of these relationships rather than their sensory properties.[5]

Examples

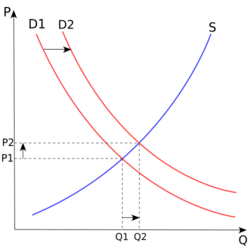

An example of this would be the demand for cars and petrol. The supply and demand for cars is represented by the figure, with the initial demand . Suppose that the initial price of cars is represented by with a quantity demanded of . If the price of petrol were to decrease by some amount, this would result in a higher quantity of cars demanded. This higher quantity demanded would cause the demand curve to shift rightward to a new position . Assuming a constant supply curve of cars, the new increased quantity demanded will be at with a new increased price . Other examples include automobiles and fuel, mobile phones and cellular service, printer and cartridge, among others.

Perfect complement

A perfect complement is a good that must be consumed with another good. The indifference curve of a perfect complement exhibits a right angle, as illustrated by the figure.[6] Such preferences can be represented by a Leontief utility function.

Few goods behave as perfect complements.[6] One example is a left shoe and a right; shoes are naturally sold in pairs, and the ratio between sales of left and right shoes will never shift noticeably from 1:1.

The degree of complementarity, however, does not have to be mutual; it can be measured by the cross price elasticity of demand. In the case of video games, a specific video game (the complement good) has to be consumed with a video game console (the base good). It does not work the other way: a video game console does not have to be consumed with that game.

Example

In marketing, complementary goods give additional market power to the producer. It allows vendor lock-in by increasing switching costs. A few types of pricing strategy exist for a complementary good and its base good:

- Pricing the base good at a relatively low price - this approach allows easy entry by consumers (e.g. low-price consumer printer vs. high-price cartridge)

- Pricing the base good at a relatively high price to the complementary good - this approach creates a barrier to entry and exit (e.g., a costly car vs inexpensive gas)

Gross complements

Sometimes the complement-relationship between two goods is not intuitive and must be verified by inspecting the cross-elasticity of demand using market data.

Mosak's definition states "a good is a gross complement of if is negative, where for denotes the ordinary individual demand for a certain good." In fact, in Mosak's case, is not a gross complement of but is a gross complement of . The elasticity does not need to be symmetrical. Thus, is a gross complement of while can simultaneously be a gross substitutes for .[7]

Proof

The standard Hicks decomposition of the effect on the ordinary demand for a good of a simple price change in a good , utility level and chosen bundle is

If is a gross substitute for , the left-hand side of the equation and the first term of right-hand side are positive. By the symmetry of Mosak's perspective, evaluating the equation with respect to , the first term of right-hand side stays the same while some extreme cases exist where is large enough to make the whole right-hand-side negative. In this case, is a gross complement of . Overall, and are not symmetrical.

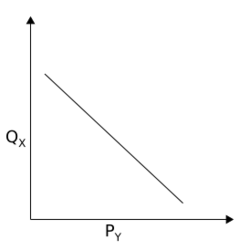

Effect of price change of complementary goods

References

- ↑ Carbaugh, Robert (2006). Contemporary Economics: An Applications Approach. Cengage Learning. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-324-31461-8. https://archive.org/details/contemporaryecon00robe/page/35.

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 88. ISBN 0-13-063085-3. https://archive.org/details/economicsprincip00osul.

- ↑ "Customer in Marketing by David Mercer". Future Observatory. http://futureobservatory.dyndns.org/9432.htm.

- ↑ Newman, Peter (2016-11-30). "Substitutes and Complements". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics: 1–7. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_1821-1. ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_1821-1?page=1. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ↑ Huh, Young Eun; Vosgerau, Joachim; Morewedge, Carey K. (2016-03-14). "Selective Sensitization: Consuming a Food Activates a Goal to Consume its Complements". Journal of Marketing Research 53 (6): 1034–1049. doi:10.1509/jmr.12.0240. ISSN 0022-2437.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mankiw, Gregory (2008). Principle of Economics. Cengage Learning. pp. 463–464. ISBN 978-0-324-58997-9.

- ↑ Mosak, Jacob L. (1944). "General equilibrium theory in international trade". Cowles Commission for Research in Economics, Monograph No. 7 (Principia Press): 33. https://dspace.gipe.ac.in/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10973/38888/GIPE-014030.pdf?sequence=3.

|