Finance:Geography and wealth

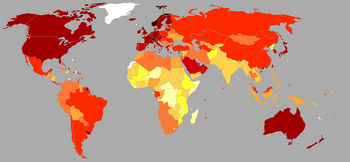

Geography and wealth have long been perceived as correlated attributes of nations.[1] Scholars such as Jeffrey D. Sachs argue that geography has a key role in the development of a nation's economic growth.[2] For instance, nations that reside along coastal regions, or those who have access to a nearby water source, are more plentiful and able to trade with neighboring nations. In addition, countries that have a tropical climate face a significant amount of difficulties such as disease, intense weather patterns, and lower agricultural productivity. This thesis is supported by the fact that the volumes of UV radiation have a negative impact on economic activity.[3] There are a number of studies confirming that spatial development in countries with higher levels of economic development differs from countries with lower levels of development.[4] The correlation between geography and a nation's wealth can be observed by examining a country's GDP (gross national product) per capita, which takes into account a nation's economic output and population.[5]

The wealthiest nations of the world with the highest standard of living tend to be those at the northern extreme of areas open to human habitation—including Northern Europe, the United States, and Canada. Within prosperous nations, wealth often increases with distance from the equator; for example, the Northeast United States has long been wealthier than its southern counterpart and northern Italy wealthier than southern regions of the country. Even within Africa this effect can be seen, as the nations farthest from the equator are wealthier. In Africa, the wealthiest nations are the three on the southern tip of the continent, South Africa , Botswana, and Namibia, and the countries of North Africa. Similarly, in South America, Argentina , Southern Brazil, Chile , and Uruguay have long been the wealthiest. Within Asia, Indonesia, located on the equator, is among the poorest. Within Central Asia, Kazakhstan is wealthier than other former Soviet Republics which border it to the south, like Uzbekistan.[6] Very often such differences in economic development are linked to the North-South issue.[7] This approach assumes an empirical division of the world into rich northern countries and poor southern countries.

In addition, the problem of heterogeneous economic development (between the industrialised north and the agrarian south) also exists within the following countries:[8]

- South and North Kazakhstan

- Southern (Osh, Batken) and northern (Bishkek city and Chui) oblasts in Kyrgyzstan.

- Southern Italy and Padania.

- Flanders and Wallonia.

- Catalonia, Basque Country and the rest of Spain .

- New England and the south-eastern states of the USA.

- Poland A and B

Researchers at Harvard's Center for International Development found in 2001 that only two tropical economies — Singapore and Hong Kong — are classified as high-income by the World Bank, while all countries within regions zoned as temperate had either middle- or high-income economies.[9]

Measurement

Most of the recent studies use national gross domestic product per person, as measured by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as the unit of comparison. Intra-national comparisons use their own data, and political divisions such as states or provinces then delineate the study areas.

Explanations

Historic

One of the first to describe and assess the phenomenon was the France philosopher Montesquieu, who asserted in the 18th century that "cold air constringes (sic) the extremities of the external fibres of the body; this increases their elasticity, and favours the return of the blood from the extreme parts to the heart. It contracts those very fibres; consequently it also increases their force. On the contrary, warm air relaxes and lengthens the extremes of the fibres; of course it diminishes their force and elasticity. People are therefore more vigorous in cold climates."[10]

The 19th century historian Henry Thomas Buckle wrote that "climate, soil, food, and the aspects of nature are the primary causes of intellectual progress—the first three indirectly, through determining the accumulation and distribution of wealth, and the last by directly influencing the accumulation and distribution of thought, the imagination being stimulated and the understanding subdued when the phenomena of the external world are sublime and terrible, the understanding being emboldened and the imagination curbed when they are small and feeble."

The first industrial revolution marked the beginning of the divergence of different nations. Alex Trew introduces a spatial take-off model that uses data on occupations in 18th century England . The model predicts changes in the spatial distribution of agricultural and manufacturing employment, which are consistent with the 1817 and 1861 data.[11] Thus, one of the historical factors influencing the geographical unevenness of wealth distribution is the degree of industrial development, catalysed by the Industrial Revolution.[12]

Climatic differences

Physiologist Jared Diamond was inspired to write his Pulitzer Prize-winning work Guns, Germs, and Steel by a question posed by Yali, a New Guinean politician: why were Europeans so much wealthier than his people? [13] In this book, Diamond argues that the Europe-Asia (Eurasia) land mass is particularly favorable for the transition of societies from hunter-gatherer to farming communities. This continent stretches much farther along the same lines of latitude than any of the other continents. Since it is much easier to transfer a domesticated species along the same latitude than it is to move it to a warmer or colder climate, any species developed at a particular latitude will be transferred across the continent in a relatively short amount of time. Thus the inhabitants of the Eurasian continent have had a built-in advantage in terms of earlier development of farming, and a greater range of plants and animals from which to choose. Oded Galor, and Ömer Özak examine existing differences in time preference across countries and regions, using pre-industrial agro-climatic characteristics.[14] The authors conclude that agro-climatic characteristics have a significant impact through culture on economic behaviour, the degree of technology adoption and human capital.

Cultural differences

One important determinant of unequal wealth in spatial contexts is significant cultural differences, including issues of attitudes to women and the slave trade. Existing research finds that the descendants of societies that traditionally practised plough farming now have less equal gender norms. The evidence is strong and persistent across countries, areas within countries and ethnic groups within areas.[15] This research is particularly relevant in terms of the division of labour and equality as a basic mechanism that contributes to economic development. Part of the work is devoted to the analysis of the slave trade as a cultural element of spatial development. Nathan Nunn, and Leonard Wantchekon explore the differences in levels of donorisation in Africa.[16] The authors find that people whose ancestors were heavily raided during the slave trade are less trusting today. The authors used several strategies to determine trust and found that the link is causal. Furthermore, it is noted that the rugged terrain in Africa provided protection to those who were raided during the slave trade. Given that the slave trade inhibited subsequent economic development, the rugged terrain in Africa has also had a historically indirect positive effect on income.[17] Another factor determining spatial development is the distance to pre-industrial technological frontiers. It has been noted that it can contribute to the emergence of a culture conducive to innovation, knowledge creation and entrepreneurship.[18]

Unequal technology development

Diamond notes that modern technologies and institutions were designed primarily in a small area of northwestern Europe, which is also supported by Galor`s book "The journey of humanity: the origins of wealth and inequality".[19] After the Scientific Revolution in Europe in the 16th century, the quality of life increased and wealth began to spread to the middle class. This included agricultural techniques, machines, and medicines. These technologies and models readily spread to areas colonized by Europe which happened to be of similar climate, such as North America and Australia. As these areas also became centres of innovation, this bias was further enhanced. Technologies from automobiles to power lines are more often designed for colder and drier regions, since most of their customers are from these regions.

The book Guns, Germs, and Steel goes on to document a feedback effect of technologies being designed for the wealthy, which makes them more wealthy and thus more able to fund technological development. He notes that the far north has not always been the wealthiest latitude; until only a few centuries ago, the wealthiest belt stretched from Southern Europe through the Middle East, northern India and southern China , which was also highlighted in the book of Mokyr "The lever of riches: Technological creativity and economic progress".[20] A dramatic shift in technologies, beginning with ocean-going ships and culminating in the Industrial Revolution, saw the most developed belt move north into northern Europe, China, and the Americas. Northern Russia became a superpower, while southern India became impoverished and colonized. Diamond argues that such dramatic changes demonstrate that the current distribution of wealth is not only due to immutable factors such as climate or race, citing the early emergence of agriculture in ancient Mesopotamia as evidence.

Diamond also notes the feedback effect in the growth of medical technology, stating that more research money goes into curing the ailments of northerners.

Disease

Ticks, mosquitos, and rats, which continue to be important disease vectors, benefit from warmer temperatures and higher humidities.[21] There has long been a malarial belt spanning the equatorial portions of the globe; the disease is especially deadly to children under the age of five.[22] Notably it has been almost impossible for most forms of northern livestock to thrive due to the endemic presence of the tsetse fly.[23] Bleakley finds empirical evidence that ankylostomosis eradication in the American South contributed to a significant increase in income that coincided with eradication activities.[24]

Jared Diamond has linked domestication of animals in Europe and Asia to the development of diseases that enabled these countries to conquer the inhabitants of other continents. The close association of people in Eurasia with their domesticated animals provided a vector for the rapid transmission of diseases. Inhabitants of lands with few domesticated species were never exposed to the same range of diseases, and so, at least on the American continents, succumbed to diseases introduced from Eurasia. These effects were exhaustively discussed in William McNeill's book Plagues and Peoples.[25] Besides, Ola Olsson, and Douglas A. Hibbs argue that geographical and initial biogeographical conditions had a decisive influence on the location and timing of the transition to sedentary agriculture, complex social organisation and, ultimately, to modern industrial production.[26]

The 2001 Harvard study mentions high infant mortality as another factor; since birth rates usually increase in compensation, women may delay their entry into the workforce to care for their younger children. The education of the surviving children then becomes difficult, perpetuating a cycle of poverty. Bloom, Canning and Fink argue that health in childhood affects productivity in adulthood.[27]

Other

- In "Climate and Scale in Economic Growth," William A. Masters and Margaret S. McMillan of Purdue University and Tufts University hypothesize that the disparity is partially due to the effects of frost in increasing soil fertility.[28]

- Hernando Zuleta, of the Universidad del Rosario, has proposed that where output fluctuations are more profound, i.e. areas that experience winter, saving is more pronounced, which leads to the adoption or creation of capital-intensive technologies.[29]

- Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson of MIT argued in 2001 that in places where Europeans faced high mortality rates, they could not settle and were more likely to set up exploitative institutions. These institutions offered no protection for private property or checks and balances against government expropriation.[30] They assert that after controlling for the effect of institutions, countries in Africa or those closer to the equator do not have lower incomes. This work has been disputed by David Albouy, who argues that European mortality rates in the study were badly mismeasured, falsely supporting its conclusion.[31]

- The authors of "Brain size, cranial morphology, climate, and time machines" assert that colder climates increase brain size, resulting in an intelligence differential.[32]

- Dao, N.T. and Davila, J. argue that when a number of geographical factors coincide, the economy may become locked in Malthusian stagnation and never develop.[33]

Impact of global warming on wealth

In a 2006 paper discussing the potential impact of global warming on wealth, John K. Horowitz of the University of Maryland predicted that a 2-degree Fahrenheit (1 °C) temperature increase across all countries would cause a decrease of 2 to 6 percent in world GDP, with a best estimate of around 3.5 percent.[34] The former United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon had expressed concern that global warming will exacerbate the existing poverty in Africa.[35] There is growing evidence that the inequality between rich and poor people's emissions within countries now exceeds the inequality between countries. High-emitting countries have more in common across international borders, regardless of where they live. It is noted that personal wealth explains more than national wealth the sources of emissions.[36]

Singapore

In a 2009 interview for New Perspective's Quarterly, Singapore's founding father Lee Kuan Yew attributed two things to the country's incredible success. One being ethnic tolerance, and the other being air conditioning, which he described as an extremely important invention that made civilization possible in the tropics.[37] Lee argued air conditioning allowed people to work during midday, previously difficult due to the tropical climate, and installed them where civil servants worked.

See also

- North-South divide

- Land (economics)

- List of countries by GDP (nominal)

- Development geography

- Measures of national income and output

- Tropical disease

References

- ↑ The Income-Temperature Relationship in a Cross-Section of Countries and its Implications for Global Warming

- ↑ Gallup, John Luke; Sachs, Jeffrey D.; Mellinger, Andrew D. (August 1999). "Geography and Economic Development". International Regional Science Review 22 (2): 179–232. doi:10.1177/016001799761012334. ISSN 0160-0176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/016001799761012334.

- ↑ Andersen, Thomas Barnebeck; Dalgaard, Carl-Johan; Selaya, Pablo (2016-02-23). "Climate and the Emergence of Global Income Differences". The Review of Economic Studies 83 (4): 1334–1363. doi:10.1093/restud/rdw006. ISSN 0034-6527. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdw006.

- ↑ Henderson, J Vernon; Squires, Tim; Storeygard, Adam; Weil, David (2017-09-11). "The Global Distribution of Economic Activity: Nature, History, and the Role of Trade1". The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133 (1): 357–406. doi:10.1093/qje/qjx030. ISSN 0033-5533. PMID 31798191. PMC 6889963. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx030.

- ↑ Sachs, Jeffrey D. (2001). "The Geography of Poverty and Wealth". Scientific American 284 (3): 70–5. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0301-70. PMID 11234509. Bibcode: 2001SciAm.284c..70S.

- ↑ Gross domestic product based on purchasing-power-parity (PPP) per capita GDP in 2005

- ↑ "North-South Problem". https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/other/bluebook/1971/1971-1-15.htm.

- ↑ Alesina, Alberto; Devleeschauwer, Arnaud; Easterly, William; Kurlat, Sergio; Wacziarg, Romain (January 2003). "Fractionalization". NBER Working Paper Series (Cambridge, MA). doi:10.3386/w9411. http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w9411.

- ↑ Sachs, Jeffrey (February 2001). "Tropical Underdevelopment". NBER Working Paper Series (Cambridge, MA). doi:10.3386/w8119. http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w8119.

- ↑ KRIESEL, KARL MARCUS (September 1968). "Montesquieu: Possibilistic Political Geographer". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 58 (3): 557–574. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1968.tb01652.x. ISSN 0004-5608. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1968.tb01652.x.

- ↑ Trew, Alex (October 2014). "Spatial takeoff in the first industrial revolution". Review of Economic Dynamics 17 (4): 707–725. doi:10.1016/j.red.2014.01.002. ISSN 1094-2025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2014.01.002.

- ↑ Oddy, Nicholas (2016). "Industrial Revolution". The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design. doi:10.5040/9781472596161-bed-online-042. ISBN 9781472596161. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472596161-bed-online-042.

- ↑ King, Arthur B. (July 2001). "Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared Diamond". The Guthrie Journal 70 (3): 119. doi:10.3138/guthrie.70.3.119. ISSN 0882-696X. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/guthrie.70.3.119.

- ↑ Galor, Oded; Özak, Ömer (2016-10-01). "The Agricultural Origins of Time Preference". American Economic Review 106 (10): 3064–3103. doi:10.1257/aer.20150020. ISSN 0002-8282. PMID 28781375. PMC 5541952. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150020.

- ↑ Alesina, Alberto; Giuliano, Paola; Nunn, Nathan (2013-05-01). "On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough". The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128 (2): 469–530. doi:10.1093/qje/qjt005. ISSN 0033-5533. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt005.

- ↑ Nunn, Nathan; Wantchekon, Leonard (2011-12-01). "The Slave Trade and the Origins of Mistrust in Africa". American Economic Review 101 (7): 3221–3252. doi:10.1257/aer.101.7.3221. ISSN 0002-8282. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.7.3221.

- ↑ Nunn, Nathan; Puga, Diego (February 2012). "Ruggedness: The Blessing of Bad Geography in Africa". Review of Economics and Statistics 94 (1): 20–36. doi:10.1162/rest_a_00161. ISSN 0034-6535. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00161.

- ↑ Özak, Ömer (2018-03-14). "Distance to the pre-industrial technological frontier and economic development". Journal of Economic Growth 23 (2): 175–221. doi:10.1007/s10887-018-9154-6. ISSN 1381-4338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10887-018-9154-6.

- ↑ Galor, Oded (2022-03-22) (in en). The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-593-18601-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=oWQ0EAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ "Joel Mokyr. <italic>The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress</italic>. New York: Oxford University Press. 1990. Pp. ix, 349. $24.95". The American Historical Review. October 1991. doi:10.1086/ahr/96.4.1164. ISSN 1937-5239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/ahr/96.4.1164.

- ↑ Prillaman, McKenzie (2022-08-12). "Climate change is making hundreds of diseases much worse" (in en). Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-02167-z. PMID 35962039. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-02167-z.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control: Statistics and Malaria's Public Health Impact

- ↑ The Impact and Implementation of Theileriosis and Trypanosomyasis on Livestock Production in Africa

- ↑ Bleakley, H. (2007-02-01). "Disease and Development: Evidence from Hookworm Eradication in the American South". The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122 (1): 73–117. doi:10.1162/qjec.121.1.73. ISSN 0033-5533. PMID 24146438. PMC 3800113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/qjec.121.1.73.

- ↑ World History Connected: Review of Plagues and Peoples

- ↑ Olsson, Ola; Hibbs, Douglas A. (May 2005). "Biogeography and long-run economic development". European Economic Review 49 (4): 909–938. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2003.08.010. ISSN 0014-2921. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2003.08.010.

- ↑ Bloom, David; Canning, David; Fink, Günther (July 2009). Disease and Development Revisited. Cambridge, MA. doi:10.3386/w15137. http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w15137.

- ↑ Climate and Scale in Economic Growth

- ↑ Seasons, Savings, and Gdp

- ↑ The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation

- ↑ The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Investigation of the Settler Mortality Data

- ↑ Brain size, cranial morphology, climate, and time machines (and Comments and Reply)

- ↑ Dao, Nguyen Thang; Dávila, Julio (September 2013). "Can geography lock a society in stagnation?". Economics Letters 120 (3): 442–446. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2013.05.031. ISSN 0165-1765. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.05.031.

- ↑ The Income-Temperature Relationship in a Cross-Section of Countries and its Implications for Global Warming

- ↑ Poor countries will suffer most from global warming, Ban Ki-moon warns

- ↑ Roston, Eric; Kaufman, Leslie; Warren, Hayley (2022-03-24). "How the World's Richest People Are Driving Global Warming" (in en). Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2022-wealth-carbon-emissions-inequality-powers-world-climate/.

- ↑ Lee, Katy (2015-03-23). "Singapore’s founding father thought air conditioning was the secret to success" (in en). https://www.vox.com/2015/3/23/8278085/singapore-lee-kuan-yew-air-conditioning.

Further reading

- Jared Diamond: Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W.W. Norton & Company, March 1997. ISBN 0-393-03891-2

- Iain Hay: Geographies of the Super-rich. Edward Elgar. 2013 ISBN 978-0-85793-568-7

- Iain Hay and Jonathan Beaverstock: Handbook on Wealth and the Super-rich. Edward Elgar ISBN 978-1-78347-403-5

- Theil, Henri, and Dongling Chen, "The Equatorial Grand Canyon," De Economist (1995). Abstract at [1]

- University of Texas at El Paso. Economic Geography: Lecture 21

- Sachs, Jeffrey D., Andrew D. Mellinger, and John L. Gallup. 2001. The Geography of Poverty and Wealth. Scientific American. March 2001.

- McNeill, William H. Plagues and People. New York: Anchor Books, 1976. ISBN 0-385-12122-9. Reprinted with new preface 1998.

|