Finance:Servicescape

Servicescape is a model developed by Booms and Bitner[1] to emphasize the impact of the physical environment in which a service process takes place. The aim of the servicescapes model is to explain behavior of people within the service environment with a view to designing environments that does not accomplish organisational goals in terms of achieving desired behavioural responses. For consumers visiting a service or retail store, the service environment is the first aspect of the service that is perceived by the customer and it is at this stage that consumers are likely to form impressions of the level of service they will receive.[2]

Booms and Bitner defined a servicescape as "the environment in which the service is assembled and in which the seller and customer interact, combined with tangible commodities that facilitate performance or communication of the service".[1] In other words, the servicescape refers to the non-human elements of the environment in which service encounters occur. The servicescape does not include: processes (e.g. methods of payment, billing, cooking, cleaning); external promotions (e.g. advertising, PR, social media, web-sites) or back-of-house (kitchen, cellars, store-rooms, housekeeping, staff change rooms), that is; spaces where customers do not normally visit.

The servicescape includes the facility's exterior (landscape, exterior design, signage, parking, surrounding environment) and interior (interior design and decor, equipment, signage, layout) and ambient conditions (air quality, temperature and lighting). In addition to its effects on customer's individual behaviors, the servicescape influences the nature and quality of customer and employee interactions, most directly in interpersonal services.[3] Companies design their servicescapes to add an atmosphere that enhances the customer experience and that will affect buyers' behavior during the service encounter.[4]

Origins, importance and influences

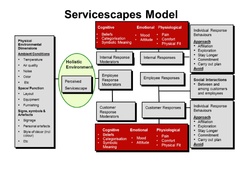

The servicescapes model is an applied stimulus-response model where the application is specific to the service sector. The model was developed by US academic, Mary Jo Bitner in 1990. It is heavily influenced by a branch of social science known as environmental psychology. In services marketing, the servicescapes model has become the dominant framework for studying and evaluating the physical environment in which service encounters occur. A service encounter can be defined as "the duration in which a customer interacts with a service. The customer's interactions with a service provider typically involve face-to-face contact with service personnel, in addition to interactions with the physical elements of the service environment including the facilities and equipment."[5]

According to Lusch and Vargo, the servicescape is an important resource that enables the firm to "channel consumer realities in certain ways".[6] Empirical studies have demonstrated that the servicescape affects both the customer's emotional and behavioural responses in service settings.[7] The servicescapes model seeks to describe all the customer interactions that occur during a service encounter and to understand how environmental elements impact on the customer's service experience.

The stimulus-response model

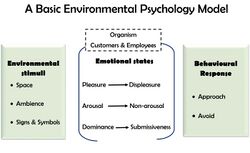

The SOR model (stimulus→organism→response model) describes the way that organisms, including customers and employees, respond to environmental stimuli (e.g. lighting, music, interior-design). In essence, the model proposes that people's responses exhibit three broad types of responses to stimuli in the external environment - physiological, emotional (affective) and behavioural responses.

- A simple stimulus-organism-response model

- Stimulus (physical environment) → Organism (customers & employees) → Response (comfort, pleasure, etc)

Environmental psychology

Environmental psychologists investigate the impact of spatial environments on behaviour. Emotional responses to environmental stimuli fall into three dimensions; pleasure, arousal and dominance. The individual's emotional state is thought to mediate the behavioural response, namely approach or avoidance behaviour towards the environment. Architects and designers can use insights from environmental psychology to design environments that promote desired emotional or behavioural outcomes.[8]

Three emotional responses are suggested in the model. These responses should be understood as a continuum, rather than a discrete emotion, and customers can be visualised as falling anywhere along the continuum as shown in the diagram.[9]

- Pleasure–displeasure refers to the emotional state reflecting the degree to which consumers and employees are satisfied with the service experience.

- Arousal–non-arousal refers to the emotional state that reflects the degree to which consumers and employees feel excited and stimulated.

- Dominance–submissiveness refers to the emotional state that reflects the degree to which consumers and employees feel in control and able to act freely within the service environment.

The individual's emotional response mediate the individual's behavioural response of Approach→ Avoidance. Approach refers to the act of physically moving towards something while avoidance interferes with people's ability to interact. In a service environment, approach behaviours might be characterised by a desire to explore an unfamiliar environment, remain in the service environment, interact with the environment and with other persons in the environment and a willingness to perform tasks within that environment. Avoid behaviours are characterised by a desire to leave the establishment, ignore the service environment, and feelings disappointment with the service experience. Environments in which people feel they lack control are unattractive. Customers often understand the concept of approach intuitively when they comment that a particular place "looks inviting" or "gives off good vibes".

The desired level of emotional arousal depends on the situation. For example, at a gym arousal might be more important than pleasure (No Pain; No gain). In a leisure setting, pleasure might be more important. If the environment pleases, then the customer will be induced to stay longer and explore all that the service has to offer. Too much arousal, however, can be counter-productive. For instance, a romantic couple might feel out of place in a busy, noisy and cluttered restaurant. Obviously, some level of arousal is necessary as a motivation to buy. The longer a customer stays in an environment, the greater the opportunities to cross-sell a range of service offerings.

Mehrabian and Russell identified two types of environment based on the degree of information processing and stimulation:[10]

- High load: Environments that are unfamiliar, novel, complex, unpredictable or crowded are high load. Such environments tend to make people feel alert and stimulated.

- Low load: Environments that are familiar, simple, unsurprising and well organised are low load. Such environments tend to make people feel relaxed, calm and even sleepy.

Activities or tasks that are low load require a more stimulating environment for optimum performance. If the task to be performed is relatively simple, routine or boring then users benefit from a slightly more stimulating environment. On the other hand, tasks that are complex or difficult may benefit from a low load environment.

The servicescapes model

The servicescapes model is an applied stimulus-organism-response model (SOR model), which treats the physical environment as the stimulus and the response is the behavior of employees and customers within the physical environment.[11] The servicescape performs four important roles - packaging - presents the outward appearance to the public; facilitator - guides the efficient flow of activities; socialiser - conveys expected roles to both employees and customers and differentiator - serves as a point of difference by signalling which segments of the market are served, positioning the organisation and conveying competitive difference.[12]

Physical environment as stimuli

The elements of the physical environment itself make up the inputs (stimuli). Environmental inputs are sensory, spatial and symbolic.[13][14] For convenience, these elements are normally considered as three broad categories including:

- Ambient conditions: Temperature, air quality, ambient noise, lighting, background music, odor, etc.

- Space/Function: Equipment such as cash registers, layout, furnishings and furniture, etc. and the ways that these elements are arranged within the space

- Signs, symbols and artefacts: Directional signage, personal artefacts (e.g. souvenirs, mementos), corporate livery and logos, style of décor (including colour schemes), symbols, etc.

Each element in the physical environment serves multiple purposes. For instance, furnishings may serve a functional role in that they provide seating where patrons can wait for friends or simply enjoy a quiet rest, but the construction materials may also serve a symbolic role in which they communicate meaning through shared understandings. Plush fabrics and generous drapery may signify an elegant, up-market venue, while plastic chairs may signify an inexpensive, family-friendly venue. Signage may provide information, but may also serve to assist customers navigate their way through a complex service environment. When evaluating the servicescape, the combined effect of all the elements must also be taken into consideration.

Ambient conditions

Ambient conditions refer to the controllable, observable stimuli such as air temperature, lighting and noise. Ambient factors, such as music used in servicescapes, have been found to influence consumer behaviors. One study found that "positively valenced music [joyful] will stimulate more thoughts and feeling than negatively valenced [mournful] music ",[15] hence, positively valenced music will make the waiting time feel longer to the customer than negatively valenced music. In a retail store, for example, changing the background music to a quicker tempo may influence the consumer to move through the space at a quicker pace, thereby improving traffic flow.[16] Evidence also suggests that playing music reduces the negative effects of waiting since it serves as a distraction.[17]

Spatial layout

According to Zeithaml et al., layout affects how easy or difficult it is to navigate through a system. Two important aspects of layout are functionality and spatial layout. Functionality refers to extent to which the equipment and layout meet the customer's goals while spatial layout refers to how physical elements are arranged, the size of those objects and the spatial arrangements between them.[18] With respect to functionality of layout, designers consider three key issues; circulation – design for traffic-flow and that encourages customers to traverse the entire store; coordination – design that combines goods and spaces in order to suggest customer needs and convenience – design that arranges items to create a degree of comfort and access for both customers and employees.[19] Spatial layout is closely related to space utilisation. Some research suggests that customers associate more spacious surroundings with higher quality services.[20]

Signs, symbols and artifacts

Signs, symbols and artifacts refer to a broader category of objects that serve multiple purposes. Signs and symbol refer to physical signals that provide cues for directional purposes, provide information about appropriate behavior within a store or servicescape and may also serve a symbolic role. Some signs perform rudimentary roles such as providing directions for navigation through a space while other more complex signs that communicate through shared meaning systems. Physical environment elements not only serve a functional or utilitarian role, but they communicate meaning in very subtle ways through symbolism. In an office environment, a big desk can symbolize the manager's power, and this can have the potential to make those who sit on the opposite side of the desk feel less relaxed and less willing to speak out.[21] The use of color also communicates at a symbolic level in ways that impact on behavior.[22]

Artifacts refer to objects that hold some type of cultural, historical or social interest for customers. They are the tangible reminders of the service experienced by consumers. Artifacts may be purpose-designed objects that serve as souvenirs or mementos of a pleasant experience. Many services, such as museums, galleries, theater's and tourist attractions, manufacture artifacts that form the basis of a merchandise collection, available for sale to visitors and guests. These artifacts, more commonly known as souvenirs, can often be retailed at prices well above market value because of the memory consumers attach to the experiential encounter.[23]

The holistic environment

When consumers enter a servicescape, they process multiple stimuli almost simultaneously. Consumers scan the ambient conditions, layout, furnishings and artefacts and aggregate them to derive an overall impression of the environment. In other words, the holistic environment is the cumulative effect of multiple stimuli, most of which are processed within a split second. These types of global judgments represent the summation of processing multiple stimuli to form a single impression. In the servicescapes model, this type of impression is known as the holistic environment.[24]

Through careful design of the physical environment and ambient conditions, managers are able to communicate the service firm's values and positioning. Ideally, the physical environment will be designed to achieve desired behavioural outcomes. Clever use of space can be used to encourage patrons to stay longer since longer stays result in more opportunities to sell services. At other times, the ambient conditions can be manipulated to encourage avoidance behaviour. For example, at the end of a busy night of trading, a bar manager might turn the air conditioning up, turn up the lights, turn off the background music and start stacking chairs on top of tables. These actions send a signal to patrons that it is closing time.

Customers and employees

The organism dimension refers to the two groups of people that make up the service encounter – customers and employees. Both groups inhabit the same physical environment, yet their perceptions of it may vary because each comes to the space for different reasons. For example, a waiter in a restaurant is likely to be pleased to see a crowded dining room because more customers means more tips. Customers, on the other hand, might be less pleased with a crowded space because the noise and queues have the potential to diminish the service experience.

Internal response moderators and mediators

A moderator is any variable with the potential to change the relationship between a dependent and independent variable. Moderating variables describe what effects will hold in certain conditions. A mediator is an intervening variable that helps to explain the relationship between two variables.[25]

In the servicescape model, a moderator is anything that increases the standard stimulus-response states of pleasure-displeasure, arousal-non-arousal or dominance-submissiveness while the response behaviour is mediated by internal responses including the cognitive, emotional and physiological responses.[26] The consumer's response to an environment depends, at least in part, on situational factors such as the purpose or reason for being in the environment.[27] For instance, a consumer who walks into a slightly chilly room, may shiver and feel a little uncomfortable. Faced with such a situation, the consumer may respond in various ways – some consumers will choose to add another layer of clothing, others will leave the environment as soon as practical, while yet others may simply endure the minor discomfort. If the consumer has a strong motivation for being in the environment, he or she is more likely to suffer the minor inconvenience of an uncomfortable ambient temperature. Thus, the consumer's motivation or reason for being in the servicescape mediates the ultimate behavioural response.

Behavioural responses

The model shows that there are different types of response - individual response (approach and avoid) and interaction responses (e.g.social interactions).

In the context of servicescapes, approach has a special meaning. It refers to how customers use the space, during and after the service encounter. Approach behaviours demonstrated during the encounter include:[28]

- Enter and explore – exhibiting a desire to explore the total service offering, a willingness to do more things, keen to learn about all the company's products and services; showing an interest in cross-selling opportunities as presented

- Stay longer – exhibiting a willingness to remain within the physical environment; longer stays present more opportunities for cross-selling, up-selling or impulse buying. Some studies have shown a correlation between length of stay and the size of average patron expenditure

- Carry out plan – exhibiting a willingness to act on information provided, fully immerse themselves in the experience and a determination to achieve personal goals

Approach behaviours demonstrated at the conclusion of the encounter or after the encounter include:

- Affiliation – A willingness to become a regular user, form intention to revisit

- Commitment – The formation of intention to become brand advocate, to provide positive recommendations, write favourable reviews or give positive word-of-mouth referrals

Avoid behaviours are characterised by a desire to leave the establishment, ignore the service environment, and feelings disappointment with the service experience.

- Social interactions refer to customer-employee interactions as well as customer-customer interactions. In some services, such as clubs, bars and tours, the act of meeting other people and interacting with other customers forms an integral part of the service experience. Managers need to think about design features that can be used to facilitate interactions between patrons. For instance, some cafeterias and casual dining establishments install communal dining tables for the express purpose of encouraging customers to mix and socialise.

Types

Bitner's pioneering work on servicescapes identified two broad types of service environment:[29]

- Lean servicescapes - environments that comprise relatively few spaces, contain few elements and involve few interactions between customers and employees. e.g. kiosks, vending machines, self-service retail outlets, fast food outlets. Designing lean environments is relatively straight-forward

- Elaborate servicescapes- environments that comprise multiple spaces, are rich in physical elements and symbolism, involve high contact services with many interactions between customers and employees. Examples include international hotels and ocean liners with guest accommodation, concierge, bars, restaurants, swimming pools, gymnasiums and other supplementary services where guests interact with multiple personnel during their stay which might extend over multiple days. Designing elaborate environments requires skilled design teams who are fully apprised of the desired behavioural outcomes and the corporate vision.

According to the model's developer, the servicescape acts like a "product's package" - by communicating a total image to customers and providing information about how to use the service.[30]

See also

- Behavioral script

- Classical conditioning

- Sensory cue

- Service blueprint

- Service design

- Services marketing

- Stimulus (psychology)

- Stimulus (physiology)

- Stimulus–response compatibility

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Booms, BH; Bitner, MJ (1981). "Marketing strategies and organisation structures for service firms". in Donnelly, J; George, WR. Marketing of Services. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association.

- ↑ Hooper and Coughlan, Daire and Joseph (2012). "The servicescape as an antecedent to service quality and behavioral intentions". Journal of Services Marketing: 271. http://eprints.maynoothuniversity.ie/6594/1/JC-Servicescape-Antecedent.pdf.

- ↑ Bitner, Mary Jo (2016). Journal of Marketing. American Marketing Association. pp. 61.

- ↑ Hooper, Daire; Coughlan, Joseph; Mullen, Michael R. (2013). "The servicescape as an antecedent to service quality and behavioral intentions". Journal of Services Marketing 27 (4): 271–280. doi:10.1108/08876041311330753. http://eprints.maynoothuniversity.ie/6594/1/JC-Servicescape-Antecedent.pdf.

- ↑ Furnham, A.and Milner, R., "The Impact of Mood on Customer Behavior: Staff Mood and Environmental Factors," Journal of Retail and Consumer Services, Vo. 20, 2013, p. 634

- ↑ Lusch, R.F. and Vargo, S.L., The Service-dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate, and Directions, Oxon, Routledge, 2015, p. 96

- ↑ Mutum, D.S., "Introduction to Service Branding and Servicescapes," in Services Marketing Cases in Emerging Markets: An Asian Perspective, Roy, Sanjit Kumar, Mutum, Dilip S., Nguyen, Bang (eds), Springer, 2015, pp 63-65, ISBN 978-3-319-32970-3

- ↑ Donovan and Rossiter, J., "Store Atmosphere: An Environmental Psychology Approach," Journal of Retailing, Vol;. 58, no. 1, 1982, pp 34-57

- ↑ Ridgway, Dawson and Bloch (1990) "Pleasure and Arousal in the Marketplace: Interpersonal differences in approach-avoidance responses," Marketing Letters, vol 1, no 2, pp139-47

- ↑ Mehrabian, A. and Russell, J.A., An Approach to Environmental Psychology, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press

- ↑ Bitner, M.J., "Evaluating Service Encounters: The Effects of Physical Surroundings and Employee Responses," Journal of Marketing, vol. 54, no. 2, 1990, pp 69-82

- ↑ Bitner, M.J., "The Servicescape," in Handbook of Services Marketing and Management, Swartz, R. and Iacobucci, D. (eds), Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 2000, pp 37-49

- ↑ Bitner, M.J., "Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Surroundings on Customers and Employees," Journal of Marketing, vol. 56, no. 2, 1992, pp 57 -71

- ↑ Katz, K.L. and Rossiter, J., "Store Atmosphere: An Environmental Psychology Approach," in Bateson, J.E.G., Managing Services Marketing: Text, Cases and Readings, Dryden, Orlando, Fl, 1991, pp 227-243

- ↑ Hul, Michael K.; Dube, Laurette; Chebat, Jean-Charles (1997-03-01). "The impact of music on consumers' reactions to waiting for services". Journal of Retailing 73 (1): 87–104. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90016-6.

- ↑ Bitner, M.J. (1992). "Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees". The Journal of Marketing 56 (2): 57–71. doi:10.1177/002224299205600205.

- ↑ Hul, M.K., Dube, L. and Chebat, J-C., " The impact of music on consumers' reactions to waiting for services," Journal of Retailing, Vol. 73, no. 1, 1997, pp 87-104

- ↑ Zeithaml, V. A., Bitner, M. J. and Gremler, D. D., Services Marketing: Integrating Customer Focus Across the Firm, 5th ed., Boston, MA, McGraw Hill, 2009

- ↑ Aghazadeh, S., "Layout Strategies for Retail Operations: A Case Study, " Management Research News, Vol. 28, no. 10, 2005, pp.31-46

- ↑ Lam, L.W., Chan, K.W. and Fong, D., "Does the Look Matter? The Impact of Casino Servicescape on Gaming Customer Satisfaction, Intention to Revisit, and Desire to Stay," International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 30, 2011, pp 558–567

- ↑ Detert, J.R. and Burris, E.R., "Can Your Employees Really Speak Freely?" Harvard Business Review, January–February, 2016 <Online:https://hbr.org/2016/01/can-your-employees-really-speak-freely>

- ↑ Nilsson, E and Ballantyne, D., "Reexamining the Place of Servicescape in Marketing: A Service-Dominant Logic Perspective," Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 28, no. 5, 2014, DOI: 10.1108/JSM-01-2013-0004

- ↑ Ardley, B., Taylor, N., McLintock, E., Martin, F. and Leonard, G., "Marketing a Memory of the World: Magna Carta and the Experiential Servicescape," Marketing Intelligence and Planning, Vol. 30, no. 6, pp.653-665, doi: 10.1108/02634501211262618

- ↑ Hoffman, K. D., Bateson, J. E.G., Elliot, G. and Birch, D., Service Marketing. Concepts, Strategies and Cases, Asia-Pacific Edition, Cengage Learning Australia, 2010, pp 209-215

- ↑ University of Wisconsin, Psychology Department, "Mediator vs Moderator" <Online: http://psych.wisc.edu/henriques/mediator.html>

- ↑ Hoffman, K.D. and Bateson, J.E. G., Services Marketing: Concepts, Strategies, & Cases, Cengage, 2017, p. 215

- ↑ Bitner, M.J., "Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Surroundings on Customers and Employees," Journal of Marketing, vol. 56, no. 2, 1992, pp 64-65

- ↑ Bitner, M.J., "Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Surroundings on Customers and Employees," Journal of Marketing, vol. 56, no. 2, 1992, pp 60-63

- ↑ Bitner, M.J., "Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Surroundings on Customers and Employees," Journal of Marketing, vol. 56, no. 2, 1992, pp 58-59

- ↑ Bitner, M.J., "Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Surroundings on Customers and Employees," Journal of Marketing, vol. 56, no. 2, 1992, p. 67

|