History:Basque prehistory

The greater Basque Country comprises the Autonomous Communities of the Basque Country and Navarre in Spain and the Northern Basque Country in France. The Prehistory of the region begins with the arrival of the first hominin settlers during the Paleolithic and lasts until the conquest and colonisation of Hispania by the Romans after the Second Punic War, who introduced comprehensive administration, writing and regular recordings.[1]

Basque people are the only Western Europeans that speak a non-Indo-European language - Euskera - without having any known contemporary European ethnic or linguistic relatives.[2] A 2015 DNA study supports the idea that the Basques descend from Neolithic farmers who mixed with local hunters and were subsequently isolated for millennia.[3][4]

Lower and Middle Paleolithic

The earliest Homo erectus migration events into Western Europe and the Basque Country had very little impact on history, culture and settlement forms. Notable is nonetheless the Atapuerca Mountains complex in northern Spain, that was inhabited in sizable communities by Homo antecessor (or Homo erectus antecessor), Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals for many generations.[5] The first substantial settler groups have arrived during the Riss-Würm interglacial period, between 150,000 and 75,000 BP, who left traces of Acheulean culture and technology. These groups usually settled in the riverine lowlands, near the rivers Ebro and Adour in the regions of Araba, Navarre, Labourd and Lower Navarre.[6]

Homo neanderthalensis Mousterian culture is introduced during the Middle Paleolithic. Neanderthals left a rather rich and long cultural sequence in northern Spain, who in the Basque Country populated the high coastal lands of Biscay and Gipuzkoa. Neanderthal remains have also been found in the Lezetxiki and Axlor caves.[7]

Upper Paleolithic

Homo sapiens first arrived on the Iberian peninsula during the Upper Paleolithic period that starts the process of replacement of Mousterian industries by the Aurignacian culture. A number of researchers suggest that the Ebro river functioned for extended periods of time as a major biological/cultural frontier that separated the anatomically modern humans in the Franco-Cantabrian region to the north from the rest of the Iberian peninsula which is occupied by Neandertals for several thousand years longer. As modern humans settled in the northern territories from around 40,000 years BCE, earliest evidence from the south dates to between 34,000 and 32,000 years BCE.[8][7] The term Vasco-Cantabrian is now often used for the coastal area of the modern Basque Country and neighbouring Cantabria.

Châtelperronian culture

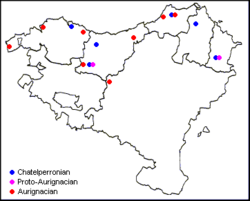

Whether Homo sapiens or Neanderthal are to be attributed to the Châtelperronian (also called Lower Périgordian) culture is debated among specialists. Nonetheless, there are Châtelperronian remains (deposited between 33,000 and 29,000 BCE) that were found in the Basque Country in caves such as Santimamiñe (Biscay), Labeko Koba, Ekain (Gipuzkoa), Isturitz (Lower Navarre) and Gatzarria (Soule) as well as the open-air site of Le Basté (Labourd).

Aurignacian culture

Artefacts of the Aurignacian culture, in particular Proto-Aurignacian objects have been found in Gatzarria and Labeko Koba.

The Aurignacian II is found in a few sites in Labourd: Le Basté and Bidart.

The Evolved Aurignacian is found mainly in Biscay and Gipuzkoa, at the sites of Lezetxiki, Aiztbitaterte IV, Koskobilo, Benta-Laperra, Kurtzia and Lumentxa.

Gravettian culture

The Gravettian period (also known as Périgordian) according to the classical French sequence, assimilates Chatelperronian and Gravettian in one single cultural complex.

Most of the findings belong to the upper and final Périgordian (V and VI): Santimamiñe, Atxurra, Bolinkoba, Amalda, Aitzbitarte III, Lezia, Isturitz and Gatzarria. The final phase of Périgordian VII is only found in Amalda (Gipuzkoa).

Solutrean culture

The Solutrean culture spans between around 18,000 to 15,000 BCE and only exists in the European south west, being coincident with the Last glacial maximum, a specially dry and cold period. Studies suggest that the higher regions of the western Pyrenees and massifs of the eastern Cantabrian Cordillera were only sparsely populated as glaciers descended to very low elevations and maximum sea level regression exposed another 5 to 12 km (3.1 to 7.5 mi) of the surrounding continental shelf. In fact Human population seems to have increased in these areas of Cantabria/Asturias, the result of a gradual influx of people, forced to abandon territories in north-western Europe that have become off limits due to maximum glacial conditions. ″The Solutrean represents technological developments in weaponry, presumably for increased efficiency and effectiveness in hunting in the face of worsening environmental conditions and increased regional human population density. In the Basque Country, Solutrean points were added onto an extant lithic technology usually characterizable as Gravettian with Noailles burins.″[9] The Basque Solutrean facies is intermediate between the Cantabrian and Pyrenean ones and is found specially in Aitzbitarte IV, Bolinkoba, Santimamiñe, Koskobilo, Isturitz, Hareguy, Ermittia and Amalda.[9][10]

Magdalenian culture

The Magdalenian culture can be found between around 15,000 and 8500 BCE and is widespread in Western - and later, Central Europe. Modern humans recolonize territories lost during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and push into northern Europe for the first time, coming from the comparatively warmer Franco-Cantabrian region, where the Magdalenian originated.[11]

Magdelenian culture and its characteristic fine art is widespread in the Basque Country. Some of the most representative sites are Santimamiñe, Lumentxa, Aitzbitarte IV, Urtiaga, Ermittia, Erralla, Ekain and Berroberria. Researchers have argued, that the original Basque people have their genetic and ethnic origins in the Magdalenian paleo-human population.[12][13]

Paleolithic art

The oldest expression of cave art in the Basque country could be in Venta La Perra (Biscay) showing animals like bear and bison, as well as abstract signs.

Nevertheless, most of the artistic expressions belong to the Magdalenian period. The most important sites are:

- Arenaza (Biscay): deer.

- Santimamiñe (Biscay): bison, horse, goat and deer.

- Ekain (Gipuzkoa) is one of the most outstanding, with 33 horses dominating the gallery. Also has bisons, deer, goats, fish, bears and some abstract signs.

- Altxerri (Gipuzkoa): bison, aurochs, goat, ibex, reindeer, deer, horse, carnivores, birds, fish and a serpent-like drawing.

- Isturitz (Low Navarre): dominated again by the horse, also includes bison, deer, goat, reindeer, a feline and negative hand impressions.

Additionally 13 sites have yielded portable art, being most notable that of Isturitz.[14][15]

Epipaleolithic

In the Epipaleolithic period, as the Last Ice Age came to an end, Magdalenian culture experienced a regionalization all around Europe, producing new localized cultural complexes. In the case of the Basque Country and the Franco-Cantabrian region as a whole, this product was Azilian, that in alter period would incorporate the geometric microliths associated with Tardenoisian and related cultures.[16]

As the climate improved gradually, population increased and colonized areas that before were out of reach. The regions of Araba and most of Navarre were hence colonized in this period.[17]

The period shows two phases, related to climatic conditions:

- The first one, of cold climate is largely a continuation of Magdalenian, with same sites and same hunt (deer mostly, but also bison, horse, goat, etc.).

- The second period, of warmer climate is that of the colonization of the South and the vanishing of reindeer. While deer were still the main capture, wild boar became more and more important. It also very noticeable the relevance acquired by seafood, with a most noticeable case in Santimamiñe, where more than 18,000 shells have been found, fish and even terrestrial snails.

As in other post-Magdalenian areas, the disappearance of realistic cave art is quite noticeable. Instead the typical Azilian decorated pebbles have been found, as well as some geometrically decorated bones and plates. Additionally personal ornaments, made up of teeth or shells, are common as well.[18]

Neolithic

The Neolithic is characterized by agriculture and animal husbandry. In the Basque Country it was a late arrival, leaving its inhabitants in a subneolithic situation almost until the beginning of metallurgy in most of the territory.

The earliest evidence of contact with Neolithic peoples is in Zatoia, northern Navarre, with pottery remains dated to c. 6000 BP. The first evidence of domestication appears in Marizulo (Gipuzkoa) c. 5300 BP. These innovations gradually expanded, though hunter-gathering activities remained being important.

Overall the vast majority of important Neolithic sites are placed in the southern part of the country (Ebro valley): Fuente Hoz, Peña Larga, Berniollo and La Renke in Araba; Zatoia, Abauntz, Peña, Padre Areso and Urbasa 11 in Navarre; Herriko Barra in Gipuzkoa.

In the early phases there is only evidence of domestication of dogs. In the advanced Neolithic, remains of ovis and capra are found in sites like Fuente Hoz (Araba) and Abauntz (Navarre). In the late phase, oxen and pig are found as well. Seafood gathering remained being an important source of food in the coast.

Lithic industry shows total continuity with the Epipaleolithic (geometric microliths) but some new elements, like sickles and hand mills, begin to appear as well. Stone polishing makes in this period its first appearance, becoming more frequent at later dates.

Pottery was initially scarce, yet it became more common and variegated at the end of Neolithic (c. 3000 BCE).

Burial customs became more defined in this period, using specific burial spots like dolmens, mounds or caves. A remarkable case is the massive burial site under rock of San Juan Ante Porta Latinam (Araba) that included 8,000 bone remains, belonging to at least 100 individuals.

The human type is sometimes defined as Western Pyrenean.[19]

Chalcolithic

The Chalcolithic (Copper and Stone) period, also known as Eneolithic or Copper Age, lasts in the Basque Country from c. 2500 to c. 1700 BCE.

While hunting was still of some importance, especially in mountain areas, food production became finally dominant.

Lithic industry persists but some tools were already made of copper (axes, knives, etc.). Gold is also used for ornaments.

An important phenomenon in the late Chalcolithic is the Bell Beaker phenomenon of pan-European extension. Also through all the period Megalithism, specially in the form of burials in dolmens, was widespread.

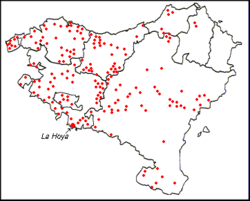

Megalithism

The Basque Country has multitude of megaliths, described as dolmens or mounds, sometimes confusingly. They are in any case burials of collective nature, placed in spots of great visibility, often on top of mountain ridges. The materials used are always of local origin.

Dolmens are the most typical, being formed by a chamber delimited by flat stones, often quite large, covered by another stone as roof. The monument was then covered by stones and earth, making up a mound.

The chambers are of two types: simple or with corridor. The first are more common, while the latter are limited to the Ebro valley area. Dolmens are also classified by their size, normally the largest ones being in lowland areas and the smaller ones in mountain zones. This was probably a function of the number of people available to build the monument.

The burial classified as mounds lack of chamber but were otherwise used like dolmens for collective burials. There are around 800 dolmens known in The Basque Country and c. 500 mounds, though some of these could be dolmens as well, in wait of excavation.

Only a few Basque dolmens have clear stratigraphies, due to the usage of removing older remains to make room for new burials. In spite of this difficulty, it's known that megalithic burial customs arrived to the Basque Country in the late Neolithic being very frequently used in the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, and, in the case of some mounds, as late as the Iron Age.

Other megalithic structures, such as standing stones (menhirs) and stone circles (cromlechs) seem to belong to later periods, specifically the Iron Age.

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age spanned from c. 1700 to c. 700 BCE. It is largely a continuity of the previous period. Gradually bronze tools replaced stone and copper ones and we can find the first fortifications, that would become very common in the last centuries of this period.

This age is divided in three subperiods:

- Early Bronze Age (c. 1700-1500 BCE): occasional use of bronze, larger pots.

- Middle Bronze Age (c. 1500-1300 BCE): generalization of bronze tools, first fortifications, first decoration of pottery (cordons).

- Late Bronze Age (c. 1300-700 BCE): bronze arrow points, variety of pottery decoration, spread of fortifications.

Megalithism continued for most of the period, yet external influences became increasingly noticeable since the Middle Bronze Age. In Araba the influence of Cogotas I is quite remarkable, while in the copper mine of Urbiola (Navarre) brachicephallic types, surely original from continental Europe, make up 30% of all remains.[19]

Iron Age

During the Iron Age in the 1st millennium BCE, with the arrival of Urnfield culture (proto-Celts) to the southern edge of the Basque Country (Ebro valley), there are some findings of iron tools and weapons. In the rest of the country it seems, from the few remains found, that the people remained in the cultural context of the Atlantic Bronze Age for some time.

Urnfield influence is limited to the Ebro valley, penetrating the Basque Country specially in Araba, where a peculiar facies of this culture, influenced as well by pre-Indo-European cultures of Aquitaine and the Iberian plateau (Cogotas I), exists.[20]

Since c. 400 BCE, there is a noticeable Iberian influence in the Ebro valley and central Navarre. Iron then became widespread, along with other advances such as the potter's wheel and an increase of production of cereal agriculture, that would allow for a larger population. Urbanization became more elaborated as well, with reticular street design in sites like La Hoya (Biasteri, Araba).

The Atlantic basin remains less developed and purely rural but there are many coincidences with the south. There are many sites, especially in the Northern Basque Country, that are awaiting archaeological excavation.

The economy became more and more centered in agriculture, specially cereals, with less importance of cattle and a marginal role for hunt. There is evidence of growing importance of bovine cattle (oxen).

Burial customs also changed, with a clear dominance of cremation in the Iron Age. The treatment of the ashes varies instead with burials in stone circles (cromlechs), mounds, caves, cists or urn fields.

The individual burial in cromlech is the most aboundant but limited to the Pyrenean region, where 851 of these funerary monuments are documented. These cromlechs have diameters of 3–7 meters, with the burial located in the middle. Corpses were not cremated inside the cromlech but in a nearby spot, with only a handful of ashes being carried to the monument in fact.

Cave, cist and urn field burials were rare, the latter are only found in two sites at the Ebro valley. Cist burials, surely related to Iberian customs, have been found at La Hoya. Additionally many young children have been found buried inside homes.

Art was mostly limited to decorative purposes, especially in pottery. Some cases of painted geometric decorations in homes, with an occasional human figure as well, have been found in the prolific sites of southern Araba (La Hoya, Alto de la Cruz). Some alleged idols and carved wooden boxes are also known of. Schematic mural painting, in caves or exposed rocky walls, dates, according to some authors, from this period as well.

On this substrate, an irregular Romanization would take place at the beginning of our age. Some towns like La Custodia (Biana, Navarre) would become clearly romanized, while others not far away, like La Hoya, would retain their original native character fully.

Sources

- ↑ "Conquest of Hispania". Heritage History. http://www.heritage-history.com/index.php?c=resources&s=war-dir&f=wars_hispania.

- ↑ "Ancient DNA cracks puzzle of Basque origins". BBC. September 7, 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-34175224.

- ↑ Günther, Torsten; Valdiosera, Cristina; Malmström, Helena; Ureña, Irene; Rodriguez-Varela, Ricardo; Sverrisdóttir, Óddny Osk; Daskalaki, Evangelia A.; Skoglund, Pontus et al. (July 29, 2015). "Ancient genomes link early farmers from Atapuerca in Spain to modern-day Basques". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (National Academy of Sciences.) 112 (38): 11917–11922. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509851112. PMID 26351665.

- ↑ Ellen Levy-Coffman. "We Are Not Our Ancestors: Evidence for Discontinuity between Prehistoric and Modern Europeans - The Basque: Reflections of a Paleolithic Past?". Journal of Genetic Genealogy. http://www.jogg.info/pages/22/Coffman.pdf.

- ↑ "Fossils Reveal Clues on Human Ancestor". The New York Times. 20 September 2007. https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E05E2D9113BF933A1575AC0A9619C8B63&scp=1&sq=dmanisi%201.8%20million&st=cse.

- ↑ "HISTORY OF THE BASQUE COUNTRY - PREHISTORY". Kondaira. http://www.kondaira.net/eng/Historia0002.html.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 João Zilhão (22 December 1998). "The Extinction of Iberian Neandertals and Its Implications for the Origins of Modern Humans in Europe". Studentski klub arheologa. Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. http://www.ffzg.unizg.hr/arheo/ska/tekstovi/extinction.pdf.

- ↑ "When did the first 'modern' human beings appear in the Iberian Peninsula?". Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona. March 15, 2010. https://phys.org/news/2010-03-modern-human-iberian-peninsula.html.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lawrence Guy STRAUS. "Human occupation of Euskalerria during the Last Glacial Maximum: the Basque Solutrean". Aranzadi - Zientzia Elkartea · Society of Sciences · Sociedad de Ciencias · Societé de Sciences. http://www.aranzadi.eus/fileadmin/docs/Munibe/1990033040AA.pdf.

- ↑ "Postglacial Coast & Inland: The Epipaleolithic-Mesolithic-Neolithic Transitions in the Vasco-Cantabrian Region". S. C. Aranzadi. Z. E. Donostia/San Sebastián. December 12, 2002. http://www.aranzadi.eus/fileadmin/docs/Munibe/2004061078AA.pdf.

- ↑ "History of the Magdalenian". Les Eyzies Tourist. http://leseyzies-tourist.info/the-magdalenian.

- ↑ John R. Bopp (2016-10-15). "The discovery of prehistory etchings in Armintxe has become a global headline". About Basque Country. https://aboutbasquecountry.eus/en/2016/10/15/the-discovery-of-prehistory-etchings-in-armintxe-has-become-a-global-headline/.

- ↑ Behar, Doron M.; Harmant, Christine; Manry, Jeremy; Van Oven, Mannis; Haak, Wolfgang; Martinez-Cruz, Begoña; Salaberria, Jasone; Oyharçabal, Bernard et al. (March 9, 2012). "The Basque Paradigm: Genetic Evidence of a Maternal Continuity in the Franco-Cantabrian Region since Pre-Neolithic Times". The American Journal of Human Genetics (ScienceDirect) 90 (3): 486–493. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.002. PMID 22365151.

- ↑ Andrew Howley (May 13, 2011). "Prehistoric Cave Art Discovered in Basque Country". National Geographic Society. https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2011/05/13/prehistoric-cave-art-discovered-in-basque-country/.

- ↑ "PREHISTORY". BASQUE COUNTRY MAGAZINE. http://www.basquecountrymagazine.com/en/prehistory.

- ↑ Alfonso Alday (2015). "Epipalaeolithic assemblages in the Western Ebro Basin (Spain): The difficult identification of cultural entities". Quaternary International (Academia Edu) 364: 144–152. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.05.041. https://www.academia.edu/28671207. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ↑ Straus, Lawrence Guy (1991). "Epipaleolithic and Mesolithic adaptations in Cantabrian Spain and Pyrenean France". Journal of World Prehistory 5: 83–104. doi:10.1007/BF00974733.

- ↑ Straus, Lawrence Guy; Eriksen, Berit Valentin; Erlandson, Jon M.; Yesner, David R. (2012-12-06). Humans at the End of the Ice Age: The Archaeology of the Pleistocene. ISBN 9781461311454. https://books.google.com/books?id=W_bxBwAAQBAJ&q=Basque+Epipaleolithic&pg=PA93. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Xabier Peñalver, Euskal Herria en la Prehistoria, 1996. ISBN:84-89077-58-4

- ↑ F. Jordá Cerdá et al., Historia de España I: Prehistoria, 1989. ISBN:84-249-1015-X

See also

- Praileaitz Cave

- Basque language

|