History:Chola dynasty

| Chola Dynasty | |

|---|---|

| Imperial, and Royal, dynasty | |

Imperial coin of Emperor Rajaraja I (985–1014). Uncertain Tamilnadu mint. Legend "Chola, conqueror of the Gangas" in Tamil, seated tiger with two fish. | |

| Country | List

|

| Etymology | Chola Nadu |

| Founder | Ilamchetchenni (first documented) |

| Final ruler | Rajendra III (main branch) |

| Deposition | 1279 |

| Cadet branches |

|

Template:Chola historyTemplate:TNhistory The Chola dynasty (Tamil: [t͡ʃoːɻɐr]) was a Tamil dynasty originating from southern India. At its height, it ruled over the Chola Empire, an expansive maritime empire. The earliest datable references to the Chola are from inscriptions dated to the 3rd century BCE during the reign of Ashoka of the Maurya empire. The Chola empire was at its peak and achieved imperialism under the Medieval Cholas in the mid-9th century CE. As one of the Three Crowned Kings of Tamilakam, along with the Chera and Pandya, the dynasty continued to govern over varying territories until the 13th century CE.

The heartland of the Cholas was the fertile valley of the Kaveri River. They ruled a significantly larger area at the height of their power from the latter half of the 9th century till the beginning of the 13th century. They unified peninsular India south of the Tungabhadra River, and held the territory as one state for three centuries between 907 and 1215 CE.[1] Under Rajaraja I and his successors Rajendra I, Rajadhiraja I, Rajendra II, Virarajendra, and Kulothunga Chola I, the empire became a military, economic and cultural powerhouse in South Asia and Southeast Asia.[2]

Origins

There is very little written evidence for the Cholas prior to the 7th century CE. The main sources of information about the early Cholas are ancient Tamil literature of the Sangam Period,[lower-alpha 1] oral traditions, religious texts, temple and copperplate inscriptions. Later medieval Cholas also claimed a long and ancient lineage. The Cholas are mentioned in Ashokan Edicts (inscribed 273 BCE–232 BCE) as one of the Mauryan empire's neighbors to the South (Ashoka Major Rock Edict No.13),[4][5] who, thought not subject to Ashoka, were on friendly terms with him.[lower-alpha 2] There are also brief references to the Chola country and its towns, ports and commerce in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (Periplus Maris Erythraei), and in the slightly later work of the geographer Ptolemy. Mahavamsa, a Buddhist text written down during the 5th century CE, recounts a number of conflicts between the inhabitants of Sri Lanka and Cholas in the 1st century BCE.[7]

A commonly held view is that Chola is, like Chera and Pandya, the name of the ruling family or clan of immemorial antiquity. The annotator Parimelazhagar said: "The charity of people with ancient lineage (such as the Cholas, the Pandyas and the Cheras) are forever generous in spite of their reduced means". Other names in common use for the Cholas are Choda,[8] Killi (கிள்ளி), Valavan (வளவன்), Sembiyan (செம்பியன்) and Cenni.[9] Killi perhaps comes from the Tamil kil (கிள்) meaning dig or cleave and conveys the idea of a digger or a worker of the land. This word often forms an integral part of early Chola names like Nedunkilli, Nalankilli and so on, but almost drops out of use in later times. Valavan is most probably connected with "valam" (வளம்) – fertility and means owner or ruler of a fertile country. Sembiyan is generally taken to mean a descendant of Shibi – a legendary hero whose self-sacrifice in saving a dove from the pursuit of a falcon figures among the early Chola legends and forms the subject matter of the Sibi Jataka among the Jataka stories of Buddhism.[10] In Tamil lexicon Chola means Soazhi or Saei denoting a newly formed kingdom, in the lines of Pandya or the old country.[11] Cenni in Tamil means Head.

History

The history of the Cholas falls into four periods: the Early Cholas of the Sangam literature, the interregnum between the fall of the Sangam Cholas and the rise of the Imperial medieval Cholas under Vijayalaya (c. 848), the dynasty of Vijayalaya, and finally the Later Chola dynasty of Kulothunga Chola I from the third quarter of the 11th century.[lower-alpha 3]

Early Cholas

The earliest Chola kings for whom there is tangible evidence are mentioned in the Sangam literature. Scholars generally agree that this literature belongs to the late centuries before the common era and the early centuries of the common era.[13] The internal chronology of this literature is still far from settled, and at present a connected account of the history of the period cannot be derived. It records the names of the kings and the princes, and of the poets who extolled them.[14]

The Sangam literature also records legends about mythical Chola kings.[15] These myths speak of the Chola king Kantaman, a supposed contemporary of the sage Agastya, whose devotion brought the river Kaveri into existence.[citation needed] Two names are prominent among those Chola kings who feature in Sangam literature: Karikala and Kocengannan.[16][17][18][19] There are no sure means of settling the order of succession, of fixing their relations with one another and with many other princelings of around the same period.[20][lower-alpha 4] Urayur (now a part of Thiruchirapalli) was their oldest capital.[15] Kaveripattinam also served as an early Chola capital.[21] The Mahavamsa mentions that a Chola prince known as Ellalan, invaded the Rajarata kingdom of Sri Lanka and conquered it in 235 BCE with the help of a Mysore army.[15][22]

Interregnum

There is not much information about the transition period of around three centuries from the end of the Sangam age (c. 300) to that in which the Pandyas and Pallavas dominated the Tamil country. An obscure dynasty, the Kalabhras invaded Tamil country, displaced the existing kingdoms and ruled during that time.[23][24][25] They were displaced by the Pallava dynasty and the Pandyan dynasty in the 6th century.[17][26] Little is known of the fate of the Cholas in Tamil land during the succeeding three centuries. The Cholas disappeared from the Tamil land almost completely in this debacle, though a branch of them can be traced towards the close of the fifth century CE in Rayalaseema—the Telugu-Cholas, whose kingdom is mentioned by Yuan Chwang in the seventh century CE.[27] Due to Kalabhra invasion and growing power of Pallavas, Cholas migrated from their native land Uraiyur to Telugu country and ruled from there as chieftains of Pallavas at least since 540 CE. Several Telugu Chola families like Renati Cholas, Pottapi Cholas, Nellore Cholas, Velanati Cholas, Nannuru Cholas, Kondidela Cholas existed and claimed descent from ancient Tamil king Karikala Chola.[28] The Cholas had to wait for another three centuries until the accession of Vijayalaya Chola belonging to Pottapi Chola family in the second quarter of the ninth century to re-establish their dynasty as independent rulers by overthrowing Pallavas and Pandyas.[29] As per inscriptions found in and around Thanjavur, Thanjavur kingdom was ruled by Mutharaiyars / Muthurajas for three centuries. Their reign was ended by Vijayalaya chola who captured Thanjavur from Ilango Mutharaiyar between 848 and 851 CE.

Epigraphy and literature provide few glimpses of the transformations that came over this line of kings during this long interval. It is certain that when the power of the Cholas fell to its lowest ebb and that of the Pandyas and Pallavas rose to the north and south of them,[18][30] this dynasty was compelled to seek refuge and patronage under their more successful rivals.[31][lower-alpha 5] In spite of their reduced powers, the Pandyas and Pallavas accepted Chola princesses in marriage, possibly out of regard for their reputation.[lower-alpha 6] Numerous Pallava inscriptions of this period mention their having fought rulers of the Chola country.[lower-alpha 7]

Imperial Cholas

The Chola Empire was founded in 848 CE by Vijayalaya, the successor of Pottapi Chola king Srikantha Chola. [35]

The Chola dynasty was at the peak of its influence and power during the 11th Century [36] Through their leadership and vision, Chola kings expanded their territory and influence. The second Chola King, Aditya I, defeated the Pallava dynasty Pandyan dynasty Parantaka I also defeated the Rashtrakuta dynasty in the battle of Vallala.[37]

Rajaraja I and Rajendra I would expand the dynasty to its imperial state, creating an influential empire in the Bay of Bengal. The Brihadeeswarar Temple was also built in this era.[38]

Rajendra I conquered Odisha and Pala dynasty of Bengal and reached the Ganges river in north India.[39] Rajendra Chola I built a new capital called Gangaikonda Cholapuram to celebrate his victories in northern India.[40] Rajendra Chola I successfully invaded the Srivijaya kingdom in Southeast Asia which led to the decline of the empire there.[41][42][43][44] He also completed the conquest of the Rajarata kingdom of Sri Lanka and sent Three diplomatic missions were sent to China in 1016, 1033, and 1077.[45][46]

The Western Chalukya empire under Satyashraya and Someshvara I tried to wriggle out of Chola domination from time to time, primarily due to the Chola influence in the Vengi kingdom.[47] The Western Chalukyas mounted several unsuccessful attempts to engage the Chola emperors in war, and except for a brief occupation of Vengi territories between 1118 and 1126 and made an alliance with Prince Vikramaditya VI.[48] Cholas always successfully controlled the Chalukyas in the western Deccan by defeating them in war and levying tribute on them.[49] With the occupation of Dharwar in North Central Karnataka by the Hoysalas under Vishnuvardhana, where he based himself with his son Narasimha I in-charge at the Hoysala capital Dwarasamudra around 1149, and with the Kalachuris occupying the Chalukyan capital for over 35 years from around 1150–1151, the Chalukya kingdom was already starting to dissolve.[50]

The Cholas under Kulothunga Chola III collaborated to the herald the dissolution of the Chalukyas by aiding Hoysalas under Veera Ballala II, the son-in-law of the Chola monarch, and defeated the Western Chalukyas in a series of wars with Someshvara IV between 1185 and 1190. The last Chalukya king's territories did not even include the erstwhile Chalukyan capitals Badami, Manyakheta or Kalyani. That was the final dissolution of Chalukyan power though the Chalukyas existed only in name since 1135–1140. But the Cholas remained stable until 1215, were absorbed by the Pandyan empire and ceased to exist by 1279.[51]

On the other hand, from 1150 CE to 1280 CE, Pandya became the staunchest opponents of the Cholas and tried to win independence for their traditional territories. Thus, this period saw constant warfare between the Cholas and the Pandyas. Besides, Cholas regularly fought with the Eastern Gangas of Kalinga. Moreover, under Chola's protection, Vengi remained largely independent. Cholas also dominated the entire eastern coast with their feudatories, the Telugu Cholas of Velanati, Nellore etc. These feudatories always aided the Cholas in their successful campaigns against the Chalukyas and levying tribute on the Kannada kingdoms. Furthermore, Cholas fought constantly with the Sinhala kings from the Rohana kingdom of Sri Lanka, who repeatedly attempted to overthrow the Chola occupation of Rajarata and unify the island. But until the later Chola king Kulottunga I, the Cholas had firm control over the area. In one such instance, the Chola king, Rajadhiraja Chola II, was able to defeat the Sinhalese, aided by their traditional ally, a confederation of five Pandya princes, and kept the control of Rajarata under Chola rule. His successor, the last great Chola monarch Kulottunga Chola III reinforced the hold of the Chola territories by quelling further rebellions and disturbances in the Rajarata area of Sri Lanka and Madurai. He also defeated Hoysala generals fought under Veera Ballala II at Karuvur. Furthermore, he also continued holding on to traditional territories in Tamil country, Eastern Gangavadi, Draksharama, Vengi, and Kalinga. However, after defeating Veera Ballala II, Kulottunga Chola III entered into a marital alliance with him through Ballala's marriage to a Chola princess, which improved the Kulottunga Chola III relationship with Hoysalas.[52][lower-alpha 8]

Overseas conquests

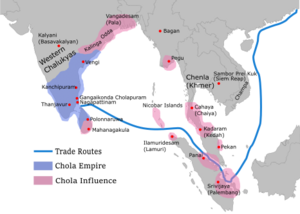

During the reign of Rajaraja Chola I and his successors Rajendra Chola I, Virarajendra Chola and Kulothunga Chola I the Chola armies invaded Sri Lanka, the Maldives and parts of Southeast Asia like Malaysia, Indonesia and Southern Thailand[54] of the Srivijaya Empire in the 11th century. Rajaraja Chola I launched several naval campaigns that resulted in the capture of Sri Lanka, Maldives and the Malabar Coast.[55] In 1025, Rajendra Chola launched naval raids on ports of Srivijaya and against the Burmese kingdom of Pegu.[56] A Chola inscription states that he captured or plundered 14 places, which have been identified with Palembang, Tambralinga and Kedah among others.[57] A second invasion was led by Virarajendra Chola, who conquered Kedah in Malaysia of Srivijaya in the late 11th century.[58] Chola invasion ultimately failed to install direct administration over Srivijaya, since the invasion was short and only meant to plunder the wealth of Srivijaya. However, this invasion gravely weakened the Srivijayan hegemony and enabled the formation of regional kingdoms. Although the invasion was not followed by direct Cholan occupation and the region was unchanged geographically, there were huge consequences in trade. Tamil traders encroached on the Srivijayan realm traditionally controlled by Malay traders and the Tamil guilds' influence increased on the Malay Peninsula and north coast of Sumatra.

Later Cholas (1070–1279)

Marital and political alliances between the Eastern Chalukyas began during the reign of Rajaraja following his invasion of Vengi. Rajaraja Chola's daughter married Chalukya prince Vimaladitya[59] and Rajendra Chola's daughter Ammanga Devi was married to the Eastern Chalukya prince Rajaraja Narendra.[60] Virarajendra Chola's son, Athirajendra Chola, was assassinated in a civil disturbance in 1070, and Kulothunga Chola I, the son of Ammanga Devi and Rajaraja Narendra, ascended the Chola throne. Thus began the Later Chola dynasty.[61]

The Later Chola dynasty was led by capable rulers such as Kulothunga Chola I, his son Vikrama Chola, other successors like Rajaraja Chola II, Rajadhiraja Chola II, and Kulothunga Chola III, who conquered Kalinga, Ilam, and Kataha. However, the rule of the later Cholas between 1218, starting with Rajaraja Chola II, to the last emperor Rajendra Chola III was not as strong as those of the emperors between 850 and 1215. Around 1118, they lost control of Vengi to the Western Chalukya and Gangavadi (southern Mysore districts) to the Hoysala Empire. However, these were only temporary setbacks, because immediately following the accession of king Vikrama Chola, the son and successor of Kulothunga Chola I, the Cholas lost no time in recovering the province of Vengi by defeating Chalukya Someshvara III and also recovering Gangavadi from the Hoysalas. The Chola empire, though not as strong as between 850 and 1150, was still largely territorially intact under Rajaraja Chola II (1146–1175) a fact attested by the construction and completion of the third grand Chola architectural marvel, the chariot-shaped Airavatesvara Temple at Dharasuram on the outskirts of modern Kumbakonam. Chola administration and territorial integrity until the rule of Kulothunga Chola III was stable and very prosperous up to 1215, but during his rule itself, the decline of the Chola power started following his defeat by Maravarman Sundara Pandiyan II in 1215–16.[62] Subsequently, the Cholas also lost control of the island of Lanka and were driven out by the revival of Sinhala power.[citation needed]

In continuation of the decline, also marked by the resurgence of the Pandyan dynasty as the most powerful rulers in South India, a lack of a controlling central administration in its erstwhile-Pandyan territories prompted a number of claimants to the Pandya throne to cause a civil war in which the Sinhalas and the Cholas were involved by proxy. Details of the Pandyan civil war and the role played by the Cholas and Sinhalas, are present in the Mahavamsa as well as the Pallavarayanpettai Inscriptions.[63][64]

Decline

The setbacks suffered during the final years of Kulothunga I left a somewhat diminished empire. Kulothunga's successors Vikrama Chola (1118–1135 CE) and Kulothunga Chola II (1133–1150 CE) were capable and compassionate leaders who took care not to involve their subjects in unnecessary and unwinnable wars.[65] Rajaraja II (1146–1173 CE), Rajadhiraja II (1166–1178 CE) and Kulothunga Chola III (1178–1218 CE) took active roles in the politics of the emerging revival of the Pandyas.[66] Meanwhile, the Chola succession was getting murkier and murkier with disputes and intrigues during the periods of Rajadhiraja II and Kulothunga III.[67]

The Cholas under Kulothunga Chola III collaborated to the herald the dissolution of the Chalukyas by aiding Hoysalas under Veera Ballala II, the son-in-law of the Chola monarch, and defeated the Western Chalukyas in a series of wars with Someshvara IV between 1185 and 1190. The last Chalukya king's territories did not even include the erstwhile Chalukyan capitals Badami, Manyakheta or Kalyani. That was the final dissolution of Chalukyan power though the Chalukyas existed only in name since 1135–1140. But the Cholas remained stable until 1215, were absorbed by the Pandyan empire and ceased to exist by 1279.[51]

His successor, the last great Chola monarch Kulottunga Chola III reinforced the hold of the Chola territories by quelling further rebellions and disturbances in the Rajarata area of Sri Lanka and Madurai. He also defeated Hoysala generals fought under Veera Ballala II at Karuvur. Eastern Gangavadi, Draksharama, Vengi, and Kalinga. However, after defeating Veera Ballala II, Kulottunga Chola III entered into a marital alliance with him through Ballala's marriage to a Chola princess, which improved the Kulottunga Chola III relationship with Hoysalas.[52]

Administration and society

Chola territory

According to Tamil tradition, the Chola country comprised the region that includes the modern-day Tiruchirapalli District, Tiruvarur District, Nagapattinam District, Ariyalur District, Perambalur district, Pudukkottai district, Thanjavur District in Tamil Nadu and Karaikal District. The river Kaveri and its tributaries dominate this landscape of generally flat country that gradually slopes towards the sea, unbroken by major hills or valleys. The river, which is also known as the Ponni (Golden) river, had a special place in the culture of Cholas. The annual floods in the Kaveri marked an occasion for celebration, known as Adiperukku, in which the whole nation took part.[citation needed]

Kaveripoompattinam on the coast near the Kaveri delta was a major port town.[15] Ptolemy knew of this, which he called Khaberis, and the other port town of Nagappattinam as the most important centres of Cholas.[68] These two towns became hubs of trade and commerce and attracted many religious faiths, including Buddhism.[lower-alpha 9] Roman ships found their way into these ports. Roman coins dating from the early centuries of the common era have been found near the Kaveri delta.[70][page needed][71]

The other major towns were Thanjavur, Uraiyur and Kudanthai, now known as Kumbakonam.[15] After Rajendra Chola moved his capital to Gangaikonda Cholapuram, Thanjavur lost its importance.[72]

Cultural contributions

Under the Cholas, the Tamil country reached new heights of excellence in art, religion, music and literature.[73] In all of these spheres, the Chola period marked the culmination of movements that had begun in an earlier age under the Pallavas.[74] Monumental architecture in the form of majestic temples and sculpture in stone and bronze reached a finesse never before achieved in India.[75]

The Chola conquest of Kadaram (Kedah) and Srivijaya, and their continued commercial contacts with the Chinese Empire, enabled them to influence the local cultures.[76] Examples of the Hindu cultural influence found today throughout Southeast Asia owe much to the legacy of the Cholas. For example, the great temple complex at Prambanan in Indonesia exhibit a number of similarities with the South Indian architecture.[77][78]

According to the Malay chronicle Sejarah Melayu, the rulers of the Malacca sultanate claimed to be descendants of the kings of the Chola empire.[79][full citation needed] Chola rule is remembered in Malaysia today as many princes there have names ending with Cholan or Chulan, one such being Raja Chulan, the Raja of Perak.[80][full citation needed][81][full citation needed]

Literature

The Imperial Chola era was the golden age of Tamil culture, marked by the importance of literature. Chola records cite many works, including the Rajarajesvara Natakam, Viranukkaviyam and Kannivana Puranam.[82]

The revival of Hinduism from its nadir during the Kalabhras spurred the construction of numerous temples and these in turn generated Shaiva and Vaishnava devotional literature.[83] Jain and Buddhist authors flourished as well, although in fewer numbers than in previous centuries.[84] Jivaka-chintamani by Tirutakkatevar and Sulamani by Tolamoli are among notable works by non-Hindu authors.[85][86][87] The grammarian Buddhamitra wrote a text on Tamil grammar called Virasoliyam.[88] Commentaries were written on the great text Tolkāppiyam which deals with grammar but which also mentions ethics of warfare.[89][90][91] Periapuranam was another remarkable literary piece of this period. This work is in a sense a national epic of the Tamil people because it treats of the lives of the saints who lived in all parts of Tamil Nadu and belonged to all classes of society, men and women, high and low, educated and uneducated.[92]

Kamban flourished during the reign of Kulothunga III. Jayamkondar's Kalingattuparani, draws a clear boundary between history and fictitious conventions.[93][94] The Tamil poet Ottakuttan was a contemporary of Kulothunga I and served at the courts of three of Kulothunga's successors.[95][96]

Nannul is a Chola era work on Tamil grammar. It discusses all five branches of grammar and, according to Berthold Spuler, is still relevant today and is one of the most distinguished normative grammars of literary Tamil.[97]

The Telugu Choda period was in particular significant for the development of Telugu literature under the patronage of the rulers. It was the age in which the great Telugu poets Tikkana, Ketana, Marana and Somana enriched the literature with their contributions. Tikkana Somayaji wrote Nirvachanottara Ramayanamu and Andhra Mahabharatamu. Abhinava Dandi Ketana wrote Dasakumaracharitramu, Vijnaneswaramu and Andhra Bhashabhushanamu. Marana wrote Markandeya Purana in Telugu. Somana wrote Basava Purana. Tikkana is one of the kavitrayam who translated Mahabharata into Telugu language.[98]

Of the devotional literature, the arrangement of the Shaivite canon into eleven books was the work of Nambi Andar Nambi, who lived close to the end of the 10th century.[99][100] However, relatively few Vaishnavite works were composed during the Later Chola period, possibly because of the rulers' apparent animosity towards them.[101]

Religion

In general, Cholas were followers of Hinduism. They were not swayed by the rise of Buddhism and Jainism as were the kings of the Pallava and Pandya dynasties. Kocengannan, an Early Chola, was celebrated in both Sangam literature and in the Shaivite canon as a Hindu saint.[19]

In popular culture

The Chola dynasty has inspired many Tamil authors.[102] The most important work of this genre is the popular Ponniyin Selvan (The son of Ponni), a historical novel in Tamil written by Kalki Krishnamurthy.[103] Written in five volumes, this narrates the story of Rajaraja Chola, dealing with the events leading up to the ascension of Uttama Chola to the Chola throne. Kalki had used the confusion in the succession to the Chola throne after the demise of Parantaka Chola II.[104] The book was serialised in the Tamil periodical Kalki during the mid-1950s.[105] The serialisation lasted for nearly five years and every week its publication was awaited with great interest.[106]

Kalki's earlier historical romance, Parthiban Kanavu, deals with the fortunes of the imaginary Chola prince Vikraman, who was supposed to have lived as a feudatory of the Pallava king Narasimhavarman I during the 7th century. The period of the story lies within the interregnum during which the Cholas were in decline before Vijayalaya Chola revived their fortunes.[107] Parthiban Kanavu was also serialised in the Kalki weekly during the early 1950s.[citation needed]

Sandilyan, another popular Tamil novelist, wrote Kadal Pura in the 1960s. It was serialised in the Tamil weekly Kumudam. Kadal Pura is set during the period when Kulothunga Chola I was in exile from the Vengi kingdom after he was denied the throne. It speculates the whereabouts of Kulothunga during this period. Sandilyan's earlier work, Yavana Rani, written in the early 1960s, is based on the life of Karikala Chola.[108] More recently, Balakumaran wrote the novel Udaiyar, which is based on the circumstances surrounding Rajaraja Chola's construction of the Brihadisvara Temple in Thanjavur.[109]

There were stage productions based on the life of Rajaraja Chola during the 1950s and in 1973 Sivaji Ganesan acted in a screen adaptation of a play titled Rajaraja Cholan. The Cholas are featured in the History of the World board game, produced by Avalon Hill.[citation needed]

The Cholas were the subject of the 2010 Tamil-language film Aayirathil Oruvan, the 2022 film Ponniyin Selvan: I and the 2023 film Ponniyin Selvan: II. The 2022 and 2023 movies were based on the novel of the same name.

See also

- Chola Empire

- Telugu Cholas of Andhra

- Chodagangas of Kalinga

- Nidugal Cholas of Karnataka

- Rajahnate of Cebu

- Rajahnate of Sanmalan

- History of Tamil Nadu

- Karungalakudi

- List of Tamil monarchs

- Tamil inscriptions in Malaysia

- Mutharaiyar dynasty

References

Notes

- ↑ The age of Sangam is established through the correlation between the evidence on foreign trade found in the poems and the writings by ancient Greek and Romans such as Periplus. K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, A History of Cyril and Lulu Charles, p 106. It is likely to extend not longer than five or six generations.[3]

- ↑ The Ashokan inscriptions speak of the Cholas in plural, implying that, in his time, there were more than one Chola.[6]

- ↑ The direct line of Cholas of the Vijayalaya dynasty came to an end with the death of Virarajendra Chola and the assassination of his son Athirajendra Chola. Kulothunga Chola I, ascended the throne in 1070.[12]

- ↑ The only evidence for the approximate period of these early kings is the Sangam literature and synchronisms with the history of Sri Lanka as given in the Mahavamsa. Gajabahu I who is said to be the contemporary of the Chera Senguttuvan, belonged to the 2nd century and this means the poems mentioning Senguttuvan and his contemporaries date to that period.[citation needed]

- ↑ Pandya Kadungon and Pallava Simhavishnu overthrew the Kalabhras. Acchchutakalaba is likely the last Kalabhra king.[30]

- ↑ Periyapuranam, a Shaivite religious work of 12th century tells us of the Pandya king Nindrasirnedumaran, who had for his queen a Chola princess.[32]

- ↑ Copperplate grants of the Pallava Buddhavarman (late 4th century) mention that the king as the "underwater fire that destroyed the ocean of the Chola army".[33] Simhavishnu (575–600) is also stated to have seized the Chola country. Mahendravarman I was called the "crown of the Chola country" in his inscriptions.[citation needed]

- ↑ "After the second Pandya War, Kulottunga undertook a campaign to check to the growth of Hoysala power in that quarter. He re-established Chola suzerainty over the Adigaimans of Tagadur, defeated a Chera ruler in battle and performed a vijayabhisheka in Karuvur (1193). His relations with the Hoysala Ballala II seem to have become friendly afterwards, for Ballala married a Chola princess".[53]

- ↑ The Buddhist work Milinda Panha dated to the early Christian era, mentions Kolapttna among the best-known sea ports on the Chola coast.[69]

Citations

- ↑ K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India, p 157

- ↑ Keay 2011, p. 215.

- ↑ Sastri (1984), p. 3

- ↑ "KING ASHOKA: His Edicts and His Times". http://www.cs.colostate.edu/~malaiya/ashoka.html.

- ↑ Ma. Ile Taṅkappā, Ā. Irā Vēṅkaṭācalapati. Red Lilies and Frightened Birds. Penguin Books India, 2011. p. xii.

- ↑ Sastri (1984), p. 20

- ↑ John Bowman,Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture, p.401

- ↑ Prasad (1988), p. 120

- ↑ Kalidos, Raju. History and Culture of the Tamils: From Prehistoric Times to the President's Rule. Vijay Publications, 1976. p. 43.

- ↑ Sastri (1984), pp. 19–20

- ↑ Archaeological News A. L. Frothingham, Jr. The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Mar., 1998), pp. 69–125

- ↑ Sastri (2002), pp. 170–172

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamil (1973) (in en). The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-03591-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=degUAAAAIAAJ&q=info:3mNeiVqlnhoJ:scholar.google.com/&pg=PR9.

- ↑ Sastri (2002), pp. 19–20, 104–106

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Tripathi (1967), p. 457

- ↑ Majumdar (1987), p. 137

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Kulke & Rothermund (2001), p. 104

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Tripathi (1967), p. 458

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Sastri (2002), p. 116

- ↑ Sastri (2002), pp. 105–106

- ↑ Sastri (2002), p. 113

- ↑ R, Narasimhacharya (1942). History of the Kannada Language. Asian Educational Services. pp. 48. ISBN 978-81-206-0559-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=yhXRDSgBuL0C.

- ↑ Sastri (2002), pp. 130, 135, 137

- ↑ Majumdar (1987), p. 139

- ↑ Thapar (1995), p. 268

- ↑ Sastri (2002), p. 135

- ↑ K.A., Nilakanta Sastri (1955) (in English). A History of South India from Prehistoric to the Fall of Vijayanagar. Oxford University Press. pp. Page=139–140.

- ↑ Hultzsch, Eugene (1911–1912). "Epigraphia Indica". Epigraphia Indica 11: 339.

- ↑ K.A., Nilakanta Sastri (1955) (in English). A History of South India from Prehistoric to the Fall of Vijayanagar. Oxford University Press. pp. Page=139–140.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Sastri (1984), p. 102

- ↑ Kulke & Rothermund (2001), p. 115

- ↑ Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 95

- ↑ Sastri (1984), pp. 104–105

- ↑ Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 31

- ↑ Sen (1999), pp. 477–478

- ↑ Sastri (2002), p. 157

- ↑ Sen (1999), pp. 373

- ↑ "Endowments to the Temple". Archaeological Survey of India. http://asi.nic.in/asi_monu_whs_cholabt_endowments.asp.

- ↑ The Dancing Girl: A History of Early India by Balaji Sadasivan p.133

- ↑ A Comprehensive History of Medieval India, by Farooqui Salma Ahmed, Salma Ahmed Farooqui p.25

- ↑ Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium by Ronald Findlay, Kevin H. O'Rourke p.67

- ↑ History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000-1800 by Geoffrey C. Gunn p.43

- ↑ Sen (2009), p. 91

- ↑ Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations by Tansen Sen p.226

- ↑ Dehejia (1990), p. xiv

- ↑ Majumdar (1987), p. 407

- ↑ Sastri (2002), p. 158

- ↑ Ancient India: Collected Essays on the Literary and Political History of Southern India by Sakkottai Krishnaswami Aiyangar p.233

- ↑ ndia: The Most Dangerous Decades by Selig S. Harrison p.31

- ↑ Sastri (2002), p. 184

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Mukund (2012), p. xlii

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), pp. 107–109

- ↑ Sastri (2002), p. 178

- ↑ Between 2 Oceans (2nd Edn): A Military History of Singapore from 1275 to 1971 by Malcolm H. Murfett, John Miksic, Brian Farell, Chiang Ming Shun p.16

- ↑ South India by Stuart Butler, Jealous p.38

- ↑ Asia: A Concise History by Arthur Cotterell p.190

- ↑ Paine (2014), p. 281

- ↑ History of Asia by B.V. Rao p.211

- ↑ Majumdar (1987), p. 405

- ↑ Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 120

- ↑ Majumdar (1987), p. 408

- ↑ Tripathi (1967), p. 471

- ↑ South Indian Inscriptions, Vol. 12

- ↑ Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), pp. 128–129

- ↑ Rajeshwari Ghose (1996). The Tyagaraja Cult in Tamilnadu: A Study in Conflict and Accommodation. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited. pp. 323–324.

- ↑ Sastri (2002), pp. 195–196

- ↑ Tripathi (1967), p. 472

- ↑ Proceedings, American Philosophical Society (1978), vol. 122, No. 6, p 414

- ↑ Sastri (1984), p. 23

- ↑ Nagasamy (1981)

- ↑ Sastri (2002), p. 107

- ↑ Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 106

- ↑ Mitter (2001), p. 2

- ↑ Sastri (2002), p. 418

- ↑ Thapar (1995), p. 403Quote: "It was, however, in bronze sculptures that the Chola craftsmen excelled, producing images rivalling the best anywhere."

- ↑ Kulke & Rothermund (2001), p. 159

- ↑ Sastri (1984), p. 789

- ↑ Kulke & Rothermund (2001), pp. 159–160

- ↑ A History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal Development by Kenneth R. Hall

- ↑ Aryatarangini, the Saga of the Indo-Aryans, by A. Kalyanaraman p.158

- ↑ India and Malaya Through the Ages: by S. Durai Raja Singam

- ↑ Sastri (1984), pp. 663–664

- ↑ Sastri (2002), p. 333

- ↑ Sastri (2002), p. 339

- ↑ Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 188

- ↑ Sastri (2002), pp. 339–340

- ↑ Ismail (1988), p. 1195

- ↑ Ancient India: Collected Essays on the Literary and Political History of southern India by Sakkottai Krishnaswami Aiyangar p.127

- ↑ The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics by Roland Greene, Stephen Cushman, Clare Cavanagh, Jahan Ramazani, Paul F. Rouzer, Harris Feinsod, David Marno, Alexandra Slessarev p.1410

- ↑ Singh (2008), p. 27

- ↑ Portraits of a Nation: History of Ancient India, by Kamlesh Kapur p.617

- ↑ Concise Encyclopaedia Of India by Kulwant Rai Gupta, Amita Gupta p.288

- ↑ Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 116

- ↑ Sastri (2002), pp. 20, 340–341

- ↑ Sastri (2002), pp. 184, 340

- ↑ Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 20

- ↑ Spuler (1975), p. 194

- ↑ www.wisdomlib.org (2018-06-23). "The Telugu Cholas of Konidena (A.D. 1050-1300) [Part 1"]. https://www.wisdomlib.org/south-asia/book/the-history-of-andhra-country/d/doc220044.html.

- ↑ Sastri (2002), pp. 342–343

- ↑ Chopra, Ravindran & Subrahmanian (2003), p. 115

- ↑ Sastri (1984), p. 681

- ↑ Das (1995), p. 108

- ↑ "Versatile writer and patriot". The Hindu. http://www.hinduonnet.com/2001/03/20/stories/13200178.htm.

- ↑ Das (1995), pp. 108–109

- ↑ "English translation of Ponniyin Selvan". The Hindu. http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/lr/2003/01/05/stories/2003010500100100.htm.

- ↑ "Lines that Speak". The Hindu. http://www.hinduonnet.com/2001/07/23/stories/13230766.htm.

- ↑ Das (1995), p. 109

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature, vol. 1, pp 631–632

- ↑ "Book review of Udaiyar". The Hindu (Chennai, India). 2005-02-22. http://www.hindu.com/br/2005/02/22/stories/2005022200101501.htm.

General sources

- Barua, Pradeep (2005), The State at War in South Asia, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-80321-344-9

- Chopra, P. N.; Ravindran, T. K.; Subrahmanian, N. (2003), History of South India: Ancient, Medieval and Modern, S. Chand & Company Ltd, ISBN 978-81-219-0153-6

- Das, Sisir Kumar (1995), History of Indian Literature (1911–1956): Struggle for Freedom – Triumph and Tragedy, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 978-81-7201-798-9

- Dehejia, Vidya (1990), The Art of the Imperial Cholas, Columbia University Press

- Devare, Hema (2009), "Cultural Implications of the Chola Maritime Fabric Trade with Southeast Asia", in Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay, Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-9-81230-937-2

- Eraly, Abraham (2011), The First Spring: The Golden Age of India, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-67008-478-4

- Gough, Kathleen (2008), Rural Society in Southeast India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52104-019-8

- Harle, J. C. (1994), The art and architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5, https://archive.org/details/artarchitectureo00harl

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (2004), "From Differences to Ethnic Solidarity Among the Tamils", in Hasbullah, S. H.; Morrison, Barrie M., Sri Lankan Society in an Era of Globalization: Struggling To Create A New Social Order, SAGE, ISBN 978-8-13210-320-2

- Ismail, M. M. (1988), "Epic - Tamil", Encyclopaedia of Indian literature, 2, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 81-260-1194-7

- Jermsawatdi, Promsak (1979), Thai Art with Indian Influences, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-8-17017-090-7

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2001), A History of India, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0

- Keay, John (12 April 2011), India: A History, Open Road + Grove/Atlantic, ISBN 978-0-8021-9550-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=0IquM4BrJ4YC

- Lucassen, Jan; Lucassen, Leo (2014), Globalising Migration History: The Eurasian Experience, BRILL, ISBN 978-9-00427-136-4

- Majumdar, R. C. (1987), Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass Publications, ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4

- Miksic, John N. (2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300_1800. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-558-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=8NJ3BgAAQBAJ&pg=PA79.

- Mitter, Partha (2001), Indian art, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-284221-3, https://archive.org/details/indianart0000mitt

- Mukherjee, Rila (2011), Pelagic Passageways: The Northern Bay of Bengal Before Colonialism, Primus Books, ISBN 978-9-38060-720-7

- Mukund, Kanakalatha (1999), The Trading World of the Tamil Merchant: Evolution of Merchant Capitalism in the Coromandel, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-8-12501-661-8

- Mukund, Kanakalatha (2012), Merchants of Tamilakam: Pioneers of International Trade, Penguin Books India, ISBN 978-0-67008-521-7

- Nagasamy, R. (1970), Gangaikondacholapuram, State Department of Archaeology, Government of Tamil Nadu

- Nagasamy, R. (1981), Tamil Coins – A study, Institute of Epigraphy, Tamil Nadu State Dept. of Archaeology

- Paine, Lincoln (2014), The Sea and Civilization: A Maritime History of the World, Atlantic Books, ISBN 978-1-78239-357-3

- Prasad, G. Durga (1988), History of the Andhras up to 1565 A. D., P. G. Publishers

- Rajasuriar, G. K. (1998), The history of the Tamils and the Sinhalese of Sri Lanka

- Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007), Historical Dictionary of the Tamils, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-81086-445-0

- Rothermund, Dietmar (1993), An Economic History of India: From Pre-colonial Times to 1991 (Reprinted ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-41508-871-8, https://archive.org/details/economichistoryo00roth

- Sadarangani, Neeti M. (2004), Bhakti Poetry in Medieval India: Its Inception, Cultural Encounter and Impact, Sarup & Sons, ISBN 978-8-17625-436-6

- Sakhuja, Vijay; Sakhuja, Sangeeta (2009), "Rajendra Chola I's Naval Expedition to South-East Asia: A Nautical Perspective", in Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay, Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-9-81230-937-2

- Sastri, K. A. N. (1984), The CōĻas, University of Madras

- Sastri, K. A. N. (2002), A History of South India: From Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar, Oxford University Press

- Scharfe, Hartmut (2002), Education in Ancient India, Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-12556-8

- Schmidt, Karl J. (1995), An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-0-76563-757-4

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999), Ancient Indian History and Civilization, New Age International, ISBN 978-8-12241-198-0

- Sen, Tansen (2009), "The Military Campaigns of Rajendra Chola and the Chola-Srivija-China Triangle", in Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay, Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-9-81230-937-2

- Singh, Upinder (2008), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-8-13171-120-0

- "South Indian Inscriptions", Archaeological Survey of India (What Is India Publishers (P) Ltd), http://www.whatisindia.com/inscriptions/, retrieved 2008-05-30

- Spuler, Bertold (1975), Handbook of Oriental Studies, Part 2, BRILL, ISBN 978-9-00404-190-5

- Stein, Burton (1980), Peasant state and society in medieval South India, Oxford University Press

- Stein, Burton (1998), A history of India, Blackwell Publishers, ISBN 978-0-631-20546-3

- Subbarayalu, Y. (2009), "A Note on the Navy of the Chola State", in Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay, Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-9-81230-937-2

- Thapar, Romila (1995), Recent Perspectives of Early Indian History, South Asia Books, ISBN 978-81-7154-556-8

- Tripathi, Rama Sankar (1967), History of Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0018-2

- Talbot, Austin Cynthia (2001), Pre-colonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19803-123-9

- Vasudevan, Geeta (2003), Royal Temple of Rajaraja: An Instrument of Imperial Cola Power, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-383-0

- Wolpert, Stanley A (1999), India, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-22172-7

External links

- UNESCO World Heritage sites – Chola temples

- Art of Cholas (archived 24 September 2015)

- Chola coins of Sri Lanka. .