History:Eastern Chalukyas

Eastern Chalukyas Chalukyas of Vengi | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 624–1189 | |||||||||||

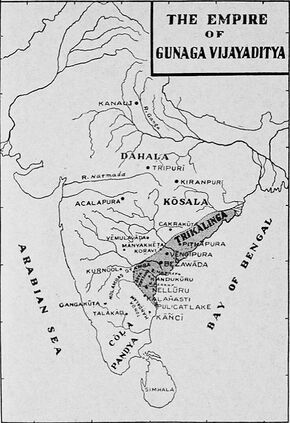

Map of India c. 753 CE. The Eastern Chalukya kingdom is shown on the eastern coast. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Pitapuram Vengi Rajahmundry | ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||||

• 624–641 | Kubja Vishnuvardhana | ||||||||||

• 1018–1061 | Rajaraja Narendra | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 624 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1189 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Eastern Chalukyas, also known as the Chalukyas of Vengi, were a dynasty that ruled parts of South India between the 7th and 12th centuries. They started out as governors of the Chalukyas of Badami in the Deccan region. Subsequently, they became a sovereign power, and ruled the Vengi region of present-day Andhra Pradesh until c. 1001 CE. They continued ruling the region as feudatories of the Medieval Cholas until 1189 CE.

Originally, the capital of the Eastern Chalukyas was located at Pishtapura (modern-day Pitapuram).[2][3][4][5] It was subsequently moved to Vengi (present-day Pedavegi, near Eluru) and then to Rajamahendravaram (now Rajahmundry). Throughout their history, the Eastern Chalukyas were the cause of many wars between the more powerful Cholas and Western Chalukyas over the control of the strategically important Vengi country. The five centuries of the Eastern Chalukya rule of Vengi saw not only the consolidation of this region into a unified whole, but also saw the efflorescence of Telugu culture, literature, poetry and art during the later half of their rule. They had marital relationship with Cholas.[6]

Origin

The Chalukyas of Vengi branched off from the Chalukyas of Badami. The Badami ruler Pulakeshin II (610–642 CE) conquered the Vengi region in eastern Deccan, after defeating the remnants of the Vishnukundina dynasty. He appointed his brother Kubja Vishnuvardhana the governor of this newly acquired territory in 624 A.D.[7] Vishnuvardhana's viceroyalty subsequently developed into an independent kingdom, possibly after Pulakeshin died fighting the Pallavas in the Battle of Vatapi.[8] Thus the Chalukyas were originally of Kannada stock.[9][10][11]

As per the Timmapuram plates of Kubja Vishnuvardhana, the progenitor of the Eastern Chalukyas, they belonged to the Manavya Gotra and were Haritputras (sons of Hariti) just like the Kadambas and Western Chalukyas.[12] From the 11th century onward, the dynasty started claiming legendary lunar dynasty origins. According to this legend, the dynasty descended from the Moon, via Budha, Pururava, the Pandavas, Satanika and Udayana. 59 unnamed descendants of Udayana ruled at Ayodhya. Their descendant Vijayaditya was killed in a battle with Trilochana Pallava, during an expedition in Dakshinapatha (Deccan). His pregnant widow was given shelter by Vishnubhatta Somayaji of Mudivemu (modern Jammalamadugu). She named her son Vishnuvardhana after her benefactor. When the boy grew up, he became the ruler of Dakshinapatha by the grace of the goddess Nanda Bhagavati.[13]

History

Between 641 AD and 705 AD some kings, except Jayasimha I and Mangi Yuvaraja, ruled for very short durations. Then followed a period of unrest characterised by family feuds and weak rulers. Meanwhile, the Rashtrakutas of Malkhed ousted Western Chalukyas of Badami. The weak rulers of Vengi had to meet the challenge of the Rashtrakutas, who overran their kingdom more than once. There was no Eastern Chalukya ruler who could check them until Gunaga Vijayaditya III came to power in 848 AD. The then Rashtrakuta ruler Amoghavarsha treated him as his ally and after Amoghavarsha's death, Vijayaditya proclaimed independence.[14]

Administration

In its early life, the Eastern Chalukya court was essentially a republic of Badami, and as generations passed, local factors gained in strength and the Vengi monarchy developed features of its own. External influences still continued to be present as the Eastern Chalukyas had long and intimate contact, either friendly or hostile, with the Pallavas, the Rashtrakutas, the Cholas and the Chalukyas of Kalyani.[15]

Type of Government

Template:South Asia in 800 CE The Eastern Chalukyan government was a monarchy based on the Hindu philosophy. The inscriptions refer to the traditional seven components of the state (Saptanga), and the eighteen Tirthas (Offices), such as:[16]

- Mantri (Minister)

- Purohita (Chaplain)

- Senapati (Commander)

- Yuvaraja (Heir-apparent)

- Dauvarika (Door keeper)

- Pradhana (Chief)

- Adhyaksha (Head of department) and so on.

No information is available as to how the work of administration was carried out. The Vishaya and Kottam were the administrative subdivisions known from records. The Karmarashtra and the Boya-Kottams are examples of these. The royal edicts (recording gifts of lands or villages) are addressed to all Naiyogi Kavallabhas, a general term containing no indication of their duties, as well as to the Grameyakas, the residents of the village granted. The Manneyas are also occasionally referred in inscriptions. They held assignments of land or revenue in different villages.[17]

Fratricidal wars and foreign invasions frequently disturbed the land. The territory was parcelled out into many small principalities (estates) held by the nobility consisting of collateral branches of the ruling house such as those of Elamanchili, Pithapuram and Mudigonda, and a few other families such as the Kona Haihayas, Kalachuris, Kolanu Saronathas, Chagis, Parichedas, Kota Vamsas, Velanadus and Kondapadamatis, closely connected by marriage ties with the Eastern Chalukyas and families who were raised to high position for their loyal services. When the Vengi ruler was strong, the nobility paid allegiance and tribute to him, but when the weakness was apparent, they were ready to join hands with the enemies against the royal house.[18]

Society

The population in the Vengi country was heterogeneous in character. Xuanzang, who travelled in the Andhra country after the establishment of the Eastern Chalukya kingdom, noted that the people were of a violent character, were of a dark complexion and were fond of arts. The society was based on hereditary caste system. Even the Buddhists and Jains who originally disregarded caste, adopted it. Besides the four traditional castes, minor communities like Boyas and Savaras (Tribal groups) also existed.[19]

The Brahmins were held in high esteem in the society. They were proficient in Vedas and Shastras and were given gifts of land and money. They held lucrative posts such as councillors, ministers and members of civil service. They even entered the army and some of them rose to positions of high command. The Kshatriyas were the ruling class. Their love of intrigue and fighting was responsible for civil war for two centuries. The Komatis (Vaishyas) were a flourishing trading community. Their organisation into a powerful guild (Nakaram) which had its headquarters in Penugonda (West Godavari) and branches in seventeen other centres had its beginnings in this period. It seems there used to be a minister for communal affairs (Samaya Mantri) in the government. The Shudras constituted the bulk of the population and there were several sub-castes among them. The army furnished a career for most of them and some of them acquired the status of Samanta Raju and Mandalika.[20]

Religion

Hinduism was the prominent religion of the Eastern Chalukya kingdom, with Shaivism being more popular than Vaishnavism. The Mahasena temple at Chebrolu became famous for its annual Jatra, which involved a procession of the deity's idol from Chebrolu to Vijayawada and back.[21] Some of the rulers, declared themselves as Parama Maheswaras (Emperors). The Buddhist religious centres eventually attained great celebrity as Siva pilgrim centres. Eastern Chalukya rulers like Vijayaditya II, Yuddhamalla I, Vijayaditya III and Bhima I took active interest in the construction of many temples. The temple establishments like dancers and musicians show that during this period, temples were not only a centre of religious worship but a fostering ground for fine arts.[22]

Buddhism, which was dominant during the Satavahanas was in decline.[21] Its monasteries were practically deserted. Due to their love of sacred relics in stupas, a few might have lingered on, Xuanzang noticed some twenty or more Buddhist monasteries in which more than three thousand monks lived.[19]

Jainism, unlike Buddhism, continued to enjoy some support from the people.[21] This is evident from the several deserted images in ruined villages all over Andhra. The inscriptions also record the construction of Jain temples and grants of land for their support from the monarchs and the people. The rulers like Kubja Vishnuvardhana, Vishnuvardhana III and Amma II patronised Jainism. Vimaladitya even became a declared follower of the doctrine of Mahavira. Vijayawada, Jenupadu, Penugonda (West Godavari) and Munugodu were the famous Jain centres of the period.[20]

Literature

Early Telugu literature was at its zenith during this period. Vipparla Inscription of Jayasimha I and the Lakshmipuram inscription of the Mangi yuvaraja were the earliest Telugu inscriptions of Eastern chalukyas found in 7 century AD.[23]

The copper plate grants of the early Eastern Chalukyas of Vengi are written in Sanskrit, but a few charters like the Aladankaram plates are written partly in Sanskrit and partly in Telugu[23]

Telugu poetry makes its early appearance in the Addanki, Kandukur and Dharmavaram inscriptions of Pandaranga, Army Chief of Vijayaditya III, in the later half of the 9th century. However, literary compositions dating earlier than 11th century CE are not clearly known. Nannaya was the poet-laureate of Rajaraja Narendra in the middle of the 11th century. An erudite scholar, he was well-versed in the Vedas, Shastras and the ancient epics, and undertook the translation of the Mahabharata into Telugu. Narayana Bhatta who was proficient in eight languages assisted him in his endeavour. Though incomplete, his work is acclaimed as a masterpiece of Telugu literature.[24]

Connection between Kannada and Telugu literature

Kubja Vishnuvardhana, the founder of the Eastern Chalukya dynasty, was the brother of the Chalukya king, Pulakeshin II. The Chalukyas therefore governed both the Karnataka and Andhra countries and patronised Telugu as well. This very likely led to a close connection to Kannada literature. A number of Telugu authors of the age also wrote in Kannada Nannaya-Bhatta's Bharata includes the Akkara, a metre considered unique to Kannada works. The same metre is also found in Yudhamalla's Bezwada inscription. Another inscription notes that Narayana-Bhatta, who assisted Nannaya-Bhatta in composing the Bharata, was a Kannada poet and was granted a village by Rajaraja Narendra in 1053 for his contribution. Kannada poets, Adikavi Pampa and Nagavarma I, also hailed from families originally from Vengi.[25]

Architecture

Due to the widely spread Shiva devotional practice in the kingdom, the Eastern Chalukyan kings undertook the construction of temples on a large scale. Vijayaditya II is credited with the construction of 108 temples. Yuddhamalla I erected a temple to Kartikeya at Vijayawada. Bhima I constructed the famous Draksharama and Chalukya Bhimavaram (Samalkot) temples. Rajaraja Narendra erected three memorial shrines at Kalidindi (West Godavari). The Eastern Chalukyas, following the Pallava and Chalukya traditions, developed their own independent style of architecture, which is visible in the Pancharama shrines (especially the Draksharama temple) and Biccavolu temples. The Golingesvara temple at Biccavolu contains some richly carved out sculptures of deities like Ardhanarisvara, Shiva, Vishnu, Agni, Chamundi and Surya.[26]

Ambapuram cave temple is Jain cave temple constructed by Eastern Chalukyas in the 7th century. During the 7th—8th century CE, a total of five Jain caves were constructed in Ambapuram and Adavinekkalam hills.[27][28]

Rulers

- Kubja Vishnuvardhana I (624 – 641 AD)

- Jayasimha I (641 – 673 AD)

- Indra Bhattaraka (673 AD, seven days)

- Vishnuvardhana II (673 – 682 AD)

- Mangi Yuvaraja (682 – 706 AD)

- Jayasimha II (706 – 718 AD)

- Kokkili (718–719 AD, six months)

- Vishnuvardhana III (719 – 755 AD)

- Vijayaditya I Bhattaraka (755 – 772 AD)

- Vishnuvardhana IV Vishnuraja (772 – 808 AD)

- Vijayaditya II (808 – 847 AD)

- Kali Vishnuvardhana V (847– 849 AD)

- Gunaga Vijayaditya III (849 – 892 AD) with his two brothers : Yuvaraja Vikramaditya I and Yuddhamalla I

- Bhima I Dronarjuna (892 – 921 AD)

- Vijayaditya IV Kollabiganda (921 AD, six months)

- Amma I Vishnuvardhana VI (921 – 927 AD)

- Vijayaditya V Beta (927 AD, fifteen days)

- Tadapa (927 AD, one month)

- Vikramaditya II (927 – 928 AD, eleven months)

- Bhima II (928 – 929 AD, eight months)

- Yuddhamalla II (929 – 935 AD)

- Bhima III Vishnuvardhana VII (935 – 947 AD)

- Amma II Vijayaditya VI (947 – 970 AD)

- Danarnava (970 – 973 AD)

- Jata Choda Bhima (973 – 999 AD) (usurp.)

- Shaktivarman I Chalukyacandra (999 – 1011 AD)

- Vimaladitya (1011–1018 AD)

- Rajaraja Narendra I Vishnuvardhana VIII (1018–1061 AD)

- Shaktivarman II (1061–1063 AD)

- Vijayaditya VII (1063–1068 AD, 1072–1075 AD)

- Rajaraja II (1075–1079)

- Virachola Vishnuvardhana IX (1079–1102)

References

- ↑ Nath Sen, Sailendra. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. p. 360. https://books.google.com/books?id=Wk4_ICH_g1EC&dq=Sen+1999+historian&pg=PR7. "They belonged to the Karnataka country and their mother tongue was Kannada"

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) (in en). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 362. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Wk4_ICH_g1EC&dq=Eastern+Chalukyas+pishtapura&pg=PA362.

- ↑ Desikachari, T. (1991) (in en). South Indian Coins. Asian Educational Services. pp. 39. ISBN 978-81-206-0155-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=lNx31XT747wC&dq=Eastern+Chalukyas+Pishtapura&pg=PA39.

- ↑ (in en) Epigraphia Indica. 29. Manager of Publications. 1987. pp. 46. https://books.google.com/books?id=lnBDAAAAYAAJ&q=pishtapura.

- ↑ Nigam, M. L. (1975) (in en). Sculptural Heritage of Andhradesa. Booklinks Corporation. pp. 16. https://books.google.com/books?id=hRtQAAAAMAAJ&q=Pishtapura.

- ↑ Rao 1994, p. 36.

- ↑ K. A. Nilakanta Sastri & N Venkataramanayya 1960, p. 471.

- ↑ N. Ramesan 1975, p. 7.

- ↑ Modali Nāgabhūṣaṇaśarma; Mudigonda Veerabhadra Sastry; Cīmakurti Śēṣagirirāvu (1995). History and culture of the Andhras. Komarraju Venkata Lakshmana Rau Vijnana Sarvaswa Sakha, Telugu University. p. 62. ISBN 81-86073-07-8. OCLC 34752106. https://archive.org/details/HistoryCultureOfTheAndhras/mode/1up.

- ↑ Altekar, A.S. Rashtrakutas And Their Times. Digital Library of India. p. 22. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.57217/page/n37/mode/2up?q=country.

- ↑ Kamat 2002, p. 6.

- ↑ A. Murali. Rattan Lal Hangloo, A. Murali. ed. New themes in Indian history: art, politics, gender, environment, and culture. Black & White, 2007. p. 24.

- ↑ N. Ramesan 1975, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Nagabhusanasarma 2008, p. 62.

- ↑ Yazdani 2009, p. 498.

- ↑ Rao 1994, pp. 53, 54.

- ↑ Kumari 2008, p. 134.

- ↑ Rao 1994, pp. 49, 50.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Rao 1994, p. 55.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Rao 1994, p. 56.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 N. Ramesan 1975, p. 2.

- ↑ Rao 1994, pp. 54, 55.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE EASTERN CHALUKYAN INSCRIPTIONS (April 2019). "SIGNIFICANCE OF THE EASTERN CHALUKYAN INSCRIPTIONS". SIGNIFICANCE OF THE EASTERN CHALUKYAN INSCRIPTIONS by Shodhganga. http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/102833/7/07_chapter-ii.pdf.

- ↑ Rao 1994, p. 48.

- ↑ Narasimhacharya, Ramanujapuram (1988) (in en). History of Kannada Literature: Readership Lectures. Asian Educational Services. pp. 27, 68. ISBN 9788120603035. https://archive.org/details/historyofkannada0000nara/page/27. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Rao 1994, pp. 42, 55.

- ↑ Varma, P. Sujata (1 October 2015). "Ancient Jain temple cries for attention". The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Vijayawada/ancient-jain-temple-cries-for-attention/article7710156.ece.

- ↑ "Jain sculpture of Mahavira at Vijayawada". British Library. 21 August 1815. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/other/019wdz000001066u00027000.html.

Bibliography

- Kamat, Suryanath U (2002). A Concise history of Karnataka from pre-historic times to the present. Bangalore: Jupiter Books. ISBN 81-206-09778.

- K. A. Nilakanta Sastri; N Venkataramanayya (1960). Ghulam Yazdani. ed. The Early History of the Deccan Parts. VII: The Eastern Chāḷukyas. Oxford University Press. OCLC 59001459. http://www.dli.ernet.in/handle/2015/531155. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- N. Ramesan (1975). The Eastern Chalukyas of Vengi. Andhra Pradesh Sahithya Akademi. OCLC 4885004. http://www.dli.ernet.in/handle/2015/175058. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Durga Prasad, History of the Andhras up to 1565 A. D., P. G. Publishers, Guntur (1988)

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. (1955). A History of South India, OUP, New Delhi (Reprinted 2002).

- Rao, P. Raghunatha (1994), History And Culture Of Andhra Pradesh: From The Earliest Times To The Present Day, Sterling Publishers, ISBN 978-81-207-1719-0

- Nagabhusanasarma (2008), History and culture of the Andhras, Komarraju Venkata Lakshmana Rau Vijnana Sarvaswa Sakha, Telugu University, 1995, ISBN 9788186073070, https://books.google.com/books?id=HTluAAAAMAAJ&q=The+then+Rashtrakuta+ruler+%5B%5BAmoghavarsha%5D%5D+treated+him+as+his+ally+and+after+Amoghavarsha%27s+death,+Vijayaditya+proclaimed+independence

- Yazdani, Ghulam (2009), The Early History of the Deccan, Volume 2, Published under the authority of the Government of Andhra Pradesh by the Oxford University Press, 1961, https://books.google.com/books?id=OllDAAAAYAAJ&q=External+influences+still+continued+to+be+present+as+the+Eastern+Chalukyas+had+long+and+intimate+contact,+either+friendly+or+hostile,+with+the+%5B%5BPallavas%5D%5D,+the+%5B%5BRashtrakutas%5D%5D,+the+%5B%5BCholas%5D%5D+and+the+%5B%5BChalukyas%5D%5D+of+kalyani

- Kumari (2008), Rule Of The Chalukya-Cholas In Andhradesa, B.R. Pub. Corp., 1985, ISBN 9788170182542, https://books.google.com/books?id=mUNuAAAAMAAJ&q=The+Manneyas+are+also+occasionally+referred+in+inscriptions.+They+held+assignments+of+land+or+revenue+in+different+villages

External links