History:Kʼicheʼ kingdom of Qʼumarkaj

Qʼumarkaj (Utatlán) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.1225–1524 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Capital | Qʼumarkaj | ||||||

| Common languages | Classical Kʼicheʼ | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Ajpop | |||||||

• ~1225–1250 (first) | Bʼalam Kitze | ||||||

• ~1500–1524 (last) | Oxib Keh | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | c.1225 | ||||||

• Conquered | 1524 | ||||||

| |||||||

The Kʼicheʼ kingdom of Qʼumarkaj was a state in the highlands of modern-day Guatemala which was founded by the Kʼicheʼ (Quiché) Maya in the thirteenth century, and which expanded through the fifteenth century until it was conquered by Spanish and Nahua forces led by Pedro de Alvarado in 1524.

The Kʼicheʼ kingdom reached its height under the king Kʼiqʼab who ruled from the fortified town of Qʼumarkaj (also called by its Nahuatl name Utatlán) near the modern town of Santa Cruz del Quiché. During his rule the Kʼicheʼ ruled large areas of highland Guatemala extending into Mexico, and they subdued other Maya peoples such as the Tzʼutujil, Kaqchikel and Mam, as well as the Nahuan Pipil people.

Historical sources

The history of the Quiché Kingdom is described in a number of documents written in postcolonial times both in Spanish and in indigenous languages such as Classical Kʼicheʼ and Kaqchikel. Important sources include the Popol Vuh which, apart from the well-known mythology, also contains a history and genealogy of the Kaweq lineage such as the Título de Totonicapán. Information from these can be crosschecked with the Annals of the Cakchiquels recounting the history of the Kaqchikel vassals and later enemies of the Kʼicheʼ. A number of other títulos such as those of Sacapulas, the Cʼoyoi, Nijaib and Tamub titles each recount Kʼicheʼ history from the viewpoint of a specific Kʼicheʼ lineage. Other sources include those written by conquistadors and ecclesiastics, and administrative documents of the colonial administration.

History

Origins

The Mayan Kʼicheʼ people had lived in the highlands of Guatemala since 600 BCE but the documented history of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom began when foreigners from the Mexican Gulf coast entered the highlands via the Pasión River around 1200 CE. These invaders are known as the "kʼicheʼ forefathers" in the documental sources, because they founded what would be the three ruling lineages of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom. The invading peoples were composed of seven tribes: the three Kʼicheʼ lineages (the Nima Kʼicheʼ, the Tamub and the Ilokʼab), the forefathers of the Kaqchikel, Rabinal, Tzʼutujil peoples, and a seventh tribe called the Tepew Yaqui. Not much is known about the ethnicity of the invaders: the ethnohistoric sources[which?] state that they were unable to communicate with the indigenous Kʼicheʼ when they arrived, and that they were yaquies, meaning that they spoke Nahuatl. J.E.S. Thompson identified them as Mexicanized Putún merchants. But Carmack (1968) is of the opinion that they were probably bilingual Nahuatl and Chontal Maya speakers who were influenced by Toltec culture and arrived as conquerors rather than merchants. It is well documented that Nahuan influence in the Kʼicheʼ language already occurs in this period, and the names of the "forefathers" are better understandable as coming from Chontal and Nahuatl than from Kʼicheʼ.[1] The Kʼicheʼ forefathers brought with them their tribal Gods: the Patron God of the Kʼicheʼ tribe was the sky god Tohil.

Foundation (c. 1225–1400)

The "forefathers" conquered the indigenous highland peoples and founded a capital at Jakawitz in the Chujuyup valley. During this period the Kaqchikel, Rabinal and Tzjutujil tribes were allies of the Kʼicheʼ and subordinate to Kʼicheʼ rulership. In these days the languages of the four peoples were largely similar but as contact between the groups waned, and finally became enmity, the languages diverged becoming the distinct modern languages.[2]

The Kʼicheʼ people itself was also composed of three separate lineages, the Kʼicheʼ, the Tamubʼ and the Ilokʼabʼ. Each lineage served a different function, the Nima Kʼicheʼ were the ruling class, the Tamub were probably traders and the Ilokʼab warriors. Each lineage was further divided into sublineages which also each had their specific functions: The Kʼicheʼ sublineages were Ajaw Kʼicheʼ, Kaweq, Nijaib and Sakiq. The Tamub sublineages were Ekoamakʼ and Kakoj. The Ilokʼab sublineages were the Siqʼa and Wanija.

After conquering and settling Jakawitz under Balam Kitze, the Kʼicheʼ now ruled by Tzʼikin expanded into Rabinal territory and subdued the Poqomam with the help of the Kaqchikel. Then they went southwest to found Pismachi where a large ritual center was built. At Pismachi, both Kʼoqaib and Kʼonache ruled, but soon internal conflicts between the lineages erupted, and finally the Ilokʼabs left Pismachi and settled in a nearby town called Mukwitz Chilokʼab. During the rule of the ahpop ("man of the mat" – the title of the Kʼiche ruler) Kʼotuja the Ilokʼabs revolted against the leadership of the Nima Kʼicheʼ lineage but were soundly defeated. Kʼotuja expanded the influence of the Kʼicheʼs and tightened the political control over the Kaqchikel and Tzʼutujil peoples by marrying his family members into their ruling lineages.

Quqʼkumatz and Kʼiqʼab (c. 1400–1475)

Under Kʼotujas's son Quqʼkumatz the Nima Kʼiche lineage also left Pismachi and settled nearby at Qʼumarkaj, "place of the rotten cane". Quqʼkumatz became known as the greatest "Nagual" lord of the Kʼicheʼ and is claimed to have been able to magically transform himself into snakes, eagles, jaguars and even blood. He could fly into the sky or visit the underworld, Xibalba. Qʼuqʼumatz greatly expanded the Kʼicheʼ kingdom, first from Pismachiʼ and later from Qʼumarkaj.[3] At this time, the Kʼicheʼ were closely allied with the Kaqchikels.[4] Qʼuqʼumatz sent his daughter to marry the lord of the Kʼoja, a Maya people based in the Cuchumatan mountains, somewhere between Sacapulas and Huehuetenango.[5] Instead of marrying her and submitting to the Kʼicheʼ-Kaqchikel alliance, Tekum Sikʼom, the Kʼoja king, killed the offered bride.[6] This act initiated a war between the Kʼicheʼ-Kaqchikel of Qʼumarkaj and the Kʼoja.[6] Qʼuqʼumatz died in the resulting battle against the Kʼoja.[6]

With the death of his father in battle against the Kʼoja, his son and heir Kʼiqʼab swore vengeance, and two years later he led the Kʼicheʼ-Kaqchikel alliance against his enemies, together with the Ajpop Kʼamha (king-elect).[7] The Kʼicheʼ-led army entered Kʼoja at first light, killed Tekum Sikʼom and captured his son.[7] Kʼiqʼab recovered the bones of his father and returned to Qʼumarkaj with many prisoners and all the jade and metal that the Kʼoja possessed, after conquering various settlements in the Sacapulas area, and the Mam people near Zaculeu.[7] During the reign of Kʼiqʼab, who was particularly warlike, the Kʼicheʼ kingdom expanded to include Rabinal, Cobán, and Quetzaltenango, and extended as far west as the Okos River, near the modern border between the Chiapas coast of Mexico and Guatemalan Pacific coast.[7] With Kaqchikel help, the eastern frontier of the kingdom was pushed as far as the Motagua River and south as far as Escuintla.[8]

In 1470 a rebellion shook Qʼumarkaj during a great celebration that saw a great gathering that included representatives of all the most important highland peoples.[8] Two sons of Kʼiqʼab together with some of his vassals rebelled against their king, killing many high ranking lords, Kaqchikel warriors and members of the Kaweq lineage.[9] The rebels tried to kill Kʼiqʼab himself but he was defended by sons loyal to him in Pakaman, on the outskirts of the city.[9] As a result of the rebellion, Kʼiqʼab was forced to make concessions to the rebelling Kʼicheʼ lords.[10] The newly empowered Kʼicheʼ lords turned against their Kaqchikel allies, who were forced to flee Qʼumarkaj and found their own capital at Iximche.[10]

After the death of king Kʼiqʼab in 1475 the Kʼicheʼ were engaged in warfare against both the Tzʼutujils and the Kaqchikels, perhaps in an attempt to recover the former power of Qʼumarkaj.[11]

Decline and conquest

In the period after the death of Kʼiqʼab the weakened Kʼicheʼ continuously struggled against the Kaqchikel, the Tzʼutujil, the Rabinal, and the Pipil. Under the leadership of Tepepul the Kʼiche tried to launch a sneak attack on Iximché, whose inhabitants were weakened because of a famine, but the Kaqchikel got word of the attack and defeated the Kʼiche army. Constant warfare ensued until 1522 when a peace accord was made between the two peoples. Although the Kʼiche also experienced some military successes in this period, for example in the subordinations of the Rabinal and the peoples on the Pacific coast of Chiapas (Soconusco), the Kʼicheʼ didn't achieve the same level of hegemony as they had experienced in earlier times. From around 1495 the Aztec empire which was then at its height in central Mexico began asserting influence on the Pacific coast and into the Guatemalan highlands. Under the Aztec Tlatoani Ahuitzotl the Soconusco province which was then paying tribute to the Kʼicheʼ was conquered by the Aztecs, and when Aztec pochteca (long-distance traders) later arrived at Qʼumarkaj the Kʼicheʼ ruler 7 Noj was so embittered that he ordered them to leave his kingdom, not to return. However, in 1510 when Aztec emissaries from Moctezuma II arrived in Qʼumarkaj to request tribute from the Kʼiche they saw themselves forced to accept vassalage to the Aztecs. From 1510 to 1521 Aztec influence at Qʼumarkaj increased and the Kʼiche lord 7 Noj also married two daughters of the Aztec ruler, further cementing the Aztec lordship, by becoming his son in-law. During this period Qʼumarkaj also became known as Utatlán, the Nahuatl translation of the placename. When the Aztecs were defeated by the Spanish in 1521 they sent messengers to the Kʼicheʼ ruler that he should prepare for battle.

Before the arrival of the Spanish led army, the Kʼicheʼ were struck by the diseases the Europeans had brought to the Americas. The Kaqchikels allied themselves to the Spaniards in 1520, before they had even arrived in Guatemala, and they also told of their enemies the Kʼiche and asked for assistance against them. Cortés sent messengers to Qʼumarkaj and requested their peaceful submission to Spanish rule and a cessation of hostilities towards the Kaqchikel. The Kʼiche denied and made ready for battle.

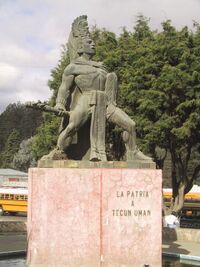

In 1524 conquistador Pedro de Alvarado arrived in Guatemala with 135 horsemen, 120 footsoldiers and 400 Aztec, Tlaxcaltecs and Cholultec allies.[12][13] They were quickly promised military assistance by the Kaqchikels. The Kʼiche knew all about the movements of the Spanish forces through their network of spies. When the army arrived at the Kʼicheʼ town of Xelajú Noj (Quetzaltenango) the Kʼicheʼ steward of the town sent word to Qʼumarkaj. The Kʼicheʼ chose Tecún Umán, a lord from Totonicapán, as their commander against the Spanish, and he was ritually prepared for the battle. He and his 8,400 warriors met the Spanish/Aztec/Kaqchikel army outside of Pinal south of Quetzalteango and were defeated. After several more defeats the Kʼicheʼ offered the Spanish vassalage and invited them to Qʼumarkaj. By way of deceit Alvarado then seized the lords of Qʼumarkaj and burned them alive. He instated two lower Kʼiche leaders as his puppet rulers and continued to subdue the other Kʼicheʼ communities in the area. Qʼumarkaj was razed and levelled to hinder the Kʼicheʼ in reestablishing themselves at the well-fortified site, and the community relocated to the nearby town of Santa Cruz del Quiché.

Social organization

In the Late Postclassic, the greater Qʼumarkaj area is estimated to have had a population of around 15,000.[14] The inhabitants of Qʼumarkaj were divided socially between the nobility and their vassals.[15] The nobles were known as the ajaw, while the vassals were known as the al kʼajol.[16] The nobility were the patrilineal descendants of the founding warlords who appear to have entered as conquerors from the Gulf coast around AD 1200 and who eventually lost their original language and adopted that of their subjects.[15][17] The nobles were regarded as sacred and bore royal imagery.[15] Their vassals served as foot-soldiers and were subject to the laws laid out by the nobility, although they could receive military titles as a result of their battlefield prowess.[15] The social divisions were deep-seated and were equivalent to strictly observed castes.[15] The merchants were a privileged class, although they had to make tributary payments to the nobility.[15] In addition to these classes, the population included rural labourers and artisans.[15] Slaves were also held and included both sentenced criminals and prisoners of war.[15]

There were twenty-four important lineages, or nimja,[16] in Qʼumarkaj, closely linked to the palaces in which the nobility attended to their duties;[18] nimja means "big house" in Kʼicheʼ, after the palace complexes that the lineages occupied.[19] Their duties included marriage negotiations and associated feasting and ceremonial lecturing.[18] These lineages were strongly patrilineal and were grouped into four larger, more powerful nimja[19] that chose the rulers of the city.[16] At the time of the Conquest, the four ruling nimja were the Kaweq, the Nijaib, the Saqik and the Ajaw Kʼicheʼ.[16] The Kaweq and the Nijaib included nine principal lineages each, the Ajaw Kʼicheʼ included four and the Saqik had two.[19] As well as choosing the king and king elect, the ruling Kaweq dynasty also had a lineage that produced the powerful priests of Qʼuqʼumatz, who may have served as stewards of the city.[20]

See also

- Cerro Quiac

- Chitinamit

- Chojolom

- Chutixtiox

Notes

- ↑ Carmack 1981:49

- ↑ Carmack 1981:69.

- ↑ Carmack 2001a, p.158.

- ↑ Carmack 2001a, pp.158–159.

- ↑ Carmack 2001a, pp.160–161.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Carmack 2001a, p.161.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Carmack 2001a, p.162.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Carmack 2001a, p.163.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Carmack 2001a, p.164.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Carmack 2001a, p.165.

- ↑ Carmack 2001a, p.166.

- ↑ Carmack, 1981:144.

- ↑ Bancroft, 1883:625-6.

- ↑ Fox 1989, p.673.n2.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 Coe 1999, p.189.

- ↑ Sharer 2000, p.490.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Coe 1999, p.190.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Carmack & Weeks 1981, p.329.

- ↑ Carmack 2001a, p.367.

References and bibliography

- Akkeren, Ruud van (2003). "Authors of the Popol Vuh". Ancient Mesoamerica 14 (2): 237–256. doi:10.1017/S0956536103142010. ISSN 0956-5361.

- Bancroft, Hubert H. (1883). History of Central America. San Francisco: Bancroft & Co. http://www.1st-hand-history.org/Hhb/06/album1.html.

- Carmack, Robert M. (1981). The Quiché Mayas of Utatlán. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1546-7. https://archive.org/details/quichemayasofuta0000carm.

- Carmack, Robert M. (1973). Quichéan Civilization:The Ethnohistoric, Ethnographic and Archaeological sources. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01963-6. https://archive.org/details/quicheanciviliza0000carm.

- Carmack, Robert M.; John M. Weeks (April 1981). "The Archaeology and Ethnohistory of Utatlan: A Conjunctive Approach". American Antiquity (Society for American Archaeology) 46 (2): 323–341. doi:10.2307/280211.

- Carmack, Robert M. (2001a) (in es). Kikʼulmatajem le Kʼicheʼaabʼ: Evolución del Reino Kʼicheʼ. Guatemala: Iximulew. ISBN 99922-56-22-2. OCLC 253481949.

- Carmack, Robert M. (2001b) (in es). Kikʼaslemaal le Kʼicheʼaabʼ: Historia Social de los Kʼicheʼs. Guatemala: Iximulew. ISBN 99922-56-19-2. OCLC 47220876.

- Carmack, Robert M.; James L. Mondloch (1983). Título de Totonicapán: texto, traducción y comentario. Mexico DF: UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Filologicas, Centro de Estudios Mayas. ISBN 968-837-376-1.

- Coe, Michael D. (1999). The Maya. Ancient peoples and places series (6th edition, fully revised and expanded ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28066-5. OCLC 59432778.

- Christenson, Allen J. (1997). "Prehistory of the Kʼichean People". Texas Notes on Precolumbian Art, Writing, and Culture 75. http://www.utmesoamerica.org/texas_notes.php. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- Edmonson, Munro S., ed (1971). The Book of Counsel: The Popol-Vuh of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. Publ. no. 35. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. OCLC 658606.

- Fox, John W. (September 1989). "On the Rise and Fall of Tuláns and Maya Segmentary States". American Anthropologist. New Series (Oxford/Arlington, Virginia: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the American Anthropological Association) 91 (3): 656–681. doi:10.1525/aa.1989.91.3.02a00080.

- Fox, John W. (1991). "The Lords of Light Versus the Lords of Dark: The Postclassic Highland Maya Ballgame". in Vernon Scarborough. The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 213–238. ISBN 0-8165-1360-0. OCLC 51873028. https://archive.org/details/mesoamericanball0000unse/page/213.

- Fox, John W. (September 1989). "On the Rise and Fall of Tuláns and Maya Segmentary States". American Anthropologist. New Series (Oxford/Arlington, Virginia: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the American Anthropological Association) 91 (3): 656–681. doi:10.1525/aa.1989.91.3.02a00080.

- Popol Vuh: the Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1985. ISBN 0-671-45241-X. OCLC 11467786.

- Sharer, Robert J. (2000). "The Maya Highlands and the Adjacent Pacific Coast". in Richard E.W. Adams. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 449–499. ISBN 0-521-35165-0. OCLC 33359444.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446. https://archive.org/details/ancientmaya0006shar.

- Weeks, John M. (1997). "Las ruinas de Utatlán: 150 años después de la publicación de Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, de John L. Stephens" (in es). Apuntes Arqueologicos 5 (1): 7–26.

[ ⚑ ] 15°1′24.7″N 91°10′19.16″W / 15.023528°N 91.1719889°W

|