Homoclinic orbit

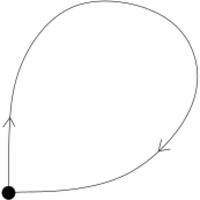

In the study of dynamical systems, a homoclinic orbit is a path through phase space which joins a saddle equilibrium point to itself. More precisely, a homoclinic orbit lies in the intersection of the stable manifold and the unstable manifold of an equilibrium. It is a heteroclinic orbit–a path between any two equilibrium points–in which the endpoints are one and the same.

Consider the continuous dynamical system described by the ordinary differential equation

Suppose there is an equilibrium at , then a solution is a homoclinic orbit if

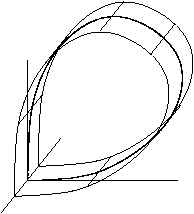

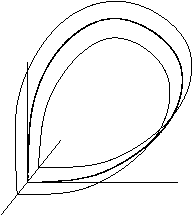

If the phase space has three or more dimensions, then it is important to consider the topology of the unstable manifold of the saddle point. The figures show two cases. First, when the stable manifold is topologically a cylinder, and secondly, when the unstable manifold is topologically a Möbius strip; in this case the homoclinic orbit is called twisted.

Discrete dynamical system

Homoclinic orbits and homoclinic points are defined in the same way for iterated functions, as the intersection of the stable set and unstable set of some fixed point or periodic point of the system.

We also have the notion of homoclinic orbit when considering discrete dynamical systems. In such a case, if is a diffeomorphism of a manifold , we say that is a homoclinic point if it has the same past and future - more specifically, if there exists a fixed (or periodic) point such that

Properties

The existence of one homoclinic point implies the existence of an infinite number of them.[1] This comes from its definition: the intersection of a stable and unstable set. Both sets are invariant by definition, which means that the forward iteration of the homoclinic point is both on the stable and unstable set. By iterating N times, the map approaches the equilibrium point by the stable set, but in every iteration it is on the unstable manifold too, which shows this property.

This property suggests that complicated dynamics arise by the existence of a homoclinic point. Indeed, Smale (1967)[2] showed that these points leads to horseshoe map like dynamics, which is associated with chaos.

Symbolic dynamics

By using the Markov partition, the long-time behaviour of a hyperbolic system can be studied using the techniques of symbolic dynamics. In this case, a homoclinic orbit has a particularly simple and clear representation. Suppose that is a finite set of M symbols. The dynamics of a point x is then represented by a bi-infinite string of symbols

A periodic point of the system is simply a recurring sequence of letters. A heteroclinic orbit is then the joining of two distinct periodic orbits. It may be written as

where is a sequence of symbols of length k, (of course, ), and is another sequence of symbols, of length m (likewise, ). The notation simply denotes the repetition of p an infinite number of times. Thus, a heteroclinic orbit can be understood as the transition from one periodic orbit to another. By contrast, a homoclinic orbit can be written as

with the intermediate sequence being non-empty, and, of course, not being p, as otherwise, the orbit would simply be .

See also

References

- ↑ Ott, Edward (1994). Chaos in Dynamical Systems. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521437998. https://archive.org/details/chaosindynamical0000otte.

- ↑ Smale, Stephen (1967). Differentiable dynamical systems. Bull. Amer. Math. Soc.73, 747–817.

- John Guckenheimer and Philip Holmes, Nonlinear Oscillations, Dynamical Systems, and Bifurcations of Vector Fields (Applied Mathematical Sciences Vol. 42), Springer

External links

- Homoclinic orbits in Henon map with Java applets and comments

|