Matroid representation

In the mathematical theory of matroids, a matroid representation is a family of vectors whose linear independence relation is the same as that of a given matroid. Matroid representations are analogous to group representations; both types of representation provide abstract algebraic structures (matroids and groups respectively) with concrete descriptions in terms of linear algebra.

A linear matroid is a matroid that has a representation, and an F-linear matroid (for a field F) is a matroid that has a representation using a vector space over F. Matroid representation theory studies the existence of representations and the properties of linear matroids.

Definitions

A (finite) matroid is defined by a finite set (the elements of the matroid) and a non-empty family of the subsets of , called the independent sets of the matroid. It is required to satisfy the properties that every subset of an independent set is itself independent, and that if one independent set is larger than a second independent set then there exists an element that can be added to to form a larger independent set. One of the key motivating examples in the formulation of matroids was the notion of linear independence of vectors in a vector space: if is a finite set or multiset of vectors, and is the family of linearly independent subsets of , then is a matroid.[1][2]

More generally, if is any matroid, then a representation of may be defined as a function that maps to a vector space , with the property that a subset of is independent if and only if is injective and is linearly independent. A matroid with a representation is called a linear matroid, and if is a vector space over field F then the matroid is called an F-linear matroid. Thus, the linear matroids are exactly the matroids that are isomorphic to the matroids defined from sets or multisets of vectors. The function will be one-to-one if and only if the underlying matroid is simple (having no two-element dependent sets). Matroid representations may also be described more concretely using matrices over a field F, with one column per matroid element and with a set of elements being independent in the matroid if and only if the corresponding set of matrix columns is linearly independent. The rank function of a linear matroid is given by the matrix rank of submatrices of this matrix, or equivalently by the dimension of the linear span of subsets of vectors.[3]

Characterization of linear matroids

Not every matroid is linear; the eight-element Vámos matroid is one of the smallest matroids that is unrepresentable over all fields.[4] If a matroid is linear, it may be representable over some but not all fields. For instance, the nine-element rank-three matroid defined by the Perles configuration is representable over the real numbers but not over the rational numbers.

Binary matroids are the matroids that can be represented over the finite field GF(2); they are exactly the matroids that do not have the uniform matroid as a minor.[5] The unimodular or regular matroids are the matroids that can be represented over all fields;[6] they can be characterized as the matroids that have none of , the Fano plane (a binary matroid with seven elements), or the dual matroid of the Fano plane as minors.[5][7] Alternatively, a matroid is regular if and only if it can be represented by a totally unimodular matrix.[8]

Rota's conjecture states that, for every finite field F, the F-linear matroids can be characterized by a finite set of forbidden minors, similar to the characterizations described above for the binary and regular matroids.[9] As of 2012, it has been proven only for fields of four or fewer elements.[5][10][11][12] For infinite fields (such as the field of the real numbers) no such characterization is possible.[13]

Field of definition

For every algebraic number field and every finite field F there is a matroid M for which F is the minimal subfield of its algebraic closure over which M can be represented: M can be taken to be of rank 3.[14]

Characteristic set

The characteristic set of a linear matroid is defined as the set of characteristics of the fields over which it is linear.[15] For every prime number p there exist infinitely many matroids whose characteristic set is the singleton set {p},[16] and for every finite set of prime numbers there exists a matroid whose characteristic set is the given finite set.[17]

If the characteristic set of a matroid is infinite, it contains zero; and if it contains zero then it contains all but finitely many primes.[18] Hence the only possible characteristic sets are finite sets not containing zero, and cofinite sets containing zero.[19] Indeed, all such sets do occur.[20]

Related classes of matroids

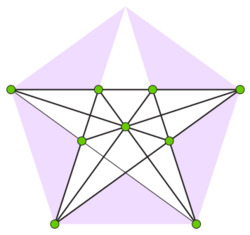

A uniform matroid has elements, and its independent sets consist of all subsets of up to of the elements. Uniform matroids may be represented by sets of vectors in general position in an -dimensional vector space. The field of representation must be large enough for there to exist vectors in general position in this vector space, so uniform matroids are F-linear for all but finitely many fields F.[21] The same is true for the partition matroids, the direct sums of the uniform matroids, as the direct sum of any two F-linear matroids is itself F-linear.

A graphic matroid is the matroid defined from the edges of an undirected graph by defining a set of edges to be independent if and only if it does not contain a cycle. Every graphic matroid is regular, and thus is F-linear for every field F.[8]

The rigidity matroids describe the degrees of freedom of mechanical linkages formed by rigid bars connected at their ends by flexible hinges. A linkage of this type may be described as a graph, with an edge for each bar and a vertex for each hinge, and for one-dimensional linkages the rigidity matroids are exactly the graphic matroids. Higher-dimensional rigidity matroids may be defined using matrices of real numbers with a structure similar to that of the incidence matrix of the underlying graph, and hence are -linear.[22][23]

Like uniform matroids and partition matroids, the gammoids, matroids representing reachability in directed graphs, are linear over every sufficiently large field. More specifically, a gammoid with elements may be represented over every field that has at least elements.[24]

The algebraic matroids are matroids defined from sets of elements of a field extension using the notion of algebraic independence. Every linear matroid is algebraic, and for fields of characteristic zero (such as the real numbers) linear and algebraic matroids coincide, but for other fields there may exist algebraic matroids that are not linear.[25]

References

- ↑ Matroid Theory, Oxford Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 3, Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 8, ISBN 9780199202508. For the rank function, see p. 26.

- ↑ Matroid Theory, Courier Dover Publications, 2010, p. 10, ISBN 9780486474397.

- ↑ (Oxley 2006), p. 12.

- ↑ (Oxley 2006), pp. 170–172, 196.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "A homotopy theorem for matroids. I, II", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 88: 144–174, 1958, doi:10.2307/1993244.

- ↑ White (1987) p.2

- ↑ White (1987) p.12

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Tutte, W. T. (1965), "Lectures on matroids", Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards 69B: 1–47, doi:10.6028/jres.069b.001, http://cdm16009.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p13011coll6/id/66650.

- ↑ "Combinatorial theory, old and new", Actes du Congrès International des Mathématiciens (Nice, 1970), Tome 3, Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1971, pp. 229–233.

- ↑ Bixby, Robert E. (1979), "On Reid's characterization of the ternary matroids", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 26 (2): 174–204, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(79)90056-X.

- ↑ "Matroid representation over GF(3)", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 26 (2): 159–173, 1979, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(79)90055-8.

- ↑ Geelen, J. F.; Gerards, A. M. H.; Kapoor, A. (2000), "The excluded minors for GF(4)-representable matroids", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 79 (2): 247–299, doi:10.1006/jctb.2000.1963, archived from the original on 2010-09-24, https://web.archive.org/web/20100924110912/http://www.math.uwaterloo.ca/~jfgeelen/publications/gf4.pdf.

- ↑ Vámos, P. (1978), "The missing axiom of matroid theory is lost forever", Journal of the London Mathematical Society, Second Series 18 (3): 403–408, doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-18.3.403.

- ↑ White, Neil, ed. (1987), Combinatorial geometries, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, 29, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 18, ISBN 0-521-33339-3, https://archive.org/details/combinatorialgeo0000unse/page/18

- ↑ Ingleton, A.W. (1971), "Representation of matroids", in Welsh, D.J.A., Combinatorial mathematics and its applications. Proceedings, Oxford, 1969, Academic Press, pp. 149–167, ISBN 0-12-743350-3

- ↑ Oxley, James; Semple, Charles; Vertigan, Dirk; Whittle, Geoff (2002), "Infinite antichains of matroids with characteristic set {p}", Discrete Mathematics 242 (1-3): 175–185, doi:10.1016/S0012-365X(00)00466-0.

- ↑ Kahn, Jeff (1982), "Characteristic sets of matroids", Journal of the London Mathematical Society, Second Series 26 (2): 207–217, doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-26.2.207.

- ↑ (Oxley 2006), p. 225.

- ↑ (Oxley 2006), p. 226.

- ↑ (Oxley 2006), p. 228.

- ↑ (Oxley 2006), p. 100.

- ↑ Graver, Jack E. (1991), "Rigidity matroids", SIAM Journal on Discrete Mathematics 4 (3): 355–368, doi:10.1137/0404032.

- ↑ "Some matroids from discrete applied geometry", Matroid theory (Seattle, WA, 1995), Contemporary Mathematics, 197, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, 1996, pp. 171–311, doi:10.1090/conm/197/02540.

- ↑ Lindström, Bernt (1973), "On the vector representations of induced matroids", The Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society 5: 85–90, doi:10.1112/blms/5.1.85.

- ↑ Ingleton, A. W. (1971), "Representation of matroids", Combinatorial Mathematics and its Applications (Proc. Conf., Oxford, 1969), London: Academic Press, pp. 149–167.

|