Medicine:Dopamine dysregulation syndrome

| Dopamine dysregulation syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

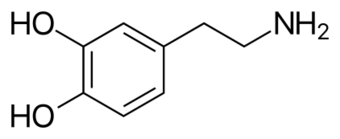

| Two-dimensional skeletal formula of the dopamine molecule. Dopamine receptor agonists mediate the development of DDS. |

Dopamine dysregulation syndrome (DDS) is a dysfunction of the reward system observed in some individuals taking dopaminergic medications for an extended length of time. It typically occurs in people with Parkinson's disease (PD) who have taken dopamine agonist medications for an extended period of time. It is characterized by problems such as addiction to medication, gambling, or sexual behavior.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The most common symptom is craving for dopaminergic medication. However other behavioral symptoms can appear independently of craving or co-occur with it.[2] Craving is an intense impulse of the subject to obtain medication even in the absence of symptoms that indicate its intake.[2] To fulfill this need the person will self-administer extra doses. When self-administration is not possible, aggressive outbursts or the use of strategies such as symptom simulation or bribery to access additional medication can also appear.[2]

Hypomania, manifesting with feelings of euphoria, omnipotence, or grandiosity, are prone to appear in those moments when medication effects are maximum; dysphoria, characterized by sadness, psychomotor slowing, fatigue or apathy are typical with dopamine replacement therapy (DRT) withdrawal.[2] Different impulse control disorders have been described including gambling, compulsive shopping, eating disorders and hypersexuality.[2] Behavioral disturbances, most commonly aggressive tendencies, are the norm. Psychosis is also common.[2]

Causes

Parkinson's disease is a common neurological disorder characterized by a degeneration of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra and a loss of dopamine in the putamen. It is described as a motor disease, but it also produces cognitive and behavioral symptoms. The most common treatment is dopamine replacement therapy, which consists in the administration of levodopa (L-Dopa) or dopamine agonists (such as pramipexole or ropinirole) to patients. Dopamine replacement therapy is well known to improve motor symptoms but its effects in cognitive and behavioral symptoms are more complex.[3] Dopamine has been related to the normal learning of stimuli with behavioral and motivational significance, attention, and most importantly the reward system.[4] In accordance with the role of dopamine in reward processing, addictive drugs stimulate dopamine release.[4] Although the exact mechanism has yet to be elucidated, the role of dopamine in the reward system and addiction has been proposed as the origin of DDS.[4] Models of addiction have been used to explain how dopamine replacement therapy produces DDS.[2] One of these models of addiction proposes that over the usage course of a drug there is a habituation to the rewarding effects that it produces at the initial stages. This habituation is thought to be dopamine mediated. With long-term administration of L-dopa the reward system gets used to it and needs higher quantities. As the user increases drug intake there is a loss of dopaminergic receptors in the striatum which acts in addition to an impairment in goal-direction mental functions to produce an enhancement of sensitization to dopamine therapy. The behavioral and mood symptoms of the syndrome are produced by the dopamine overdose.[4]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of the syndrome is clinical since there are no laboratory tests to confirm it. For diagnosis a person with documented responsiveness to medication has to increase medication intake beyond dosage needed to relieve their parkinsonian symptoms in a pathological addiction-like pattern. A current mood disorder (depression, anxiety, hypomanic state or euphoria), behavioral disorder (excessive gambling, shopping or sexual tendency, aggression, or social isolation) or an altered perception about the effect of medication also have to be present.[5] A questionnaire on the typical symptoms of DDS has also been developed and can help in the diagnosis process.[6]

Prevention

The main prevention measure proposed is the prescription of the lowest possible dose of dopamine replacement therapy to individuals at risk.[4] The minimization of the use of dopamine agonists, and of short duration formulations of L-Dopa can also decrease risk of the syndrome.[4]

Management

First choice management measure consists in the enforcement of a dopaminergic drug dosage reduction. If this decrease is maintained, dysregulation syndrome features soon decrease.[4] Cessation of dopamine agonists therapy may also be of use.[7] Some behavioral characteristics may respond to psychotherapy; and social support is important to control risk factors. In some cases antipsychotic drugs may also be of use in the presence of psychosis, aggression, gambling or hypersexuality.[4]

Based upon five case reports,[8][9] valproic acid may have efficacy in controlling the symptoms of levodopa-induced DDS that arise from the use of levodopa for the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[10][11][12]

Epidemiology

DDS is not common among PD patients. Prevalence may be around 4%.[1][5] Its prevalence is higher among males with an early onset of the disease.[2] Previous substance abuse such as heavy drinking or drug intake seems to be the main risk factor along with a history of affective disorder.[2]

History

PD was first formally described in 1817;[13] however, L-dopa did not enter clinical practice until almost 1970.[14][15] In these initial works there were already reports of neuropsychiatric complications.[15] During the following decades cases featuring DDS symptoms in relation to dopamine therapy such as hypersexuality, gambling or punding, appeared.[16][17][18] DDS was first described as a syndrome in the year 2000.[19] Three years later the first review articles on the syndrome were written, showing an increasing awareness of the DDS importance.[1][4][2] Diagnostic criteria were proposed in 2005.[5]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Dopamine dysregulation syndrome, addiction and behavioral changes in Parkinson's disease". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 14 (4): 273–80. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.09.007. PMID 17988927.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 "Compulsive use of dopamine replacement therapy in Parkinson's disease: reward systems gone awry?". Lancet Neurol 2 (10): 595–604. October 2003. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00529-5. PMID 14505581.

- ↑ Cools R (2006). "Dopaminergic modulation of cognitive function-implications for L-DOPA treatment in Parkinson's disease". Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.024. PMID 15935475.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 "Dopamine dysregulation syndrome in Parkinson's disease". Curr. Opin. Neurol. 17 (4): 393–8. August 2004. doi:10.1097/01.wco.0000137528.23126.41. PMID 15247533.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Prevalence and clinical features of hedonistic homeostatic dysregulation in Parkinson's disease". Mov. Disord. 20 (1): 77–81. January 2005. doi:10.1002/mds.20288. PMID 15390130.

- ↑ "Hedonistic homeostatic dysregulation in Parkinson's disease: a short screening questionnaire". Neurol. Sci. 24 (3): 205–6. October 2003. doi:10.1007/s10072-003-0132-0. PMID 14598089.

- ↑ "Resolution of dopamine dysregulation syndrome following cessation of dopamine agonist therapy in Parkinson's disease". J Clin Neurosci 15 (2): 205–8. February 2008. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2006.04.019. PMID 18068992.

- ↑ "Valproate as a treatment for dopamine dysregulation syndrome (DDS) in Parkinson's disease". Journal of Neurology 260 (2): 521–517. February 2013. doi:10.1007/s00415-012-6669-1. PMID 23007193.

- ↑ "Successful treatment of dopamine dysregulation syndrome with valproic acid". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 26 (3): E3. 2014. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13060126. PMID 25093777.

- ↑ "Gambling disorder during dopamine replacement treatment in Parkinson's disease: a comprehensive review". Biomed Res Int 2014: 1–9. 2014. doi:10.1155/2014/728038. PMID 25114917.

- ↑ "Treatment of cognitive, psychiatric, and affective disorders associated with Parkinson's disease". Neurotherapeutics 11 (1): 78–91. 2014. doi:10.1007/s13311-013-0238-x. PMID 24288035.

- ↑ "Impulsive and compulsive behaviors in Parkinson's disease". Annu Rev Clin Psychol 10: 553–80. 2014. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153705. PMID 24313567.

- ↑ Parkinson J (2002). "An essay on the shaking palsy". J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 14 (2): 223–36; discussion 222. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.14.2.223. PMID 11983801.

- ↑ Cotzias GC (March 1968). "L-Dopa for Parkinsonism". N. Engl. J. Med. 278 (11): 630. doi:10.1056/NEJM196803142781127. PMID 5637779.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Treatment of parkinsonism with levodopa". Arch. Neurol. 21 (4): 343–54. October 1969. doi:10.1001/archneur.1969.00480160015001. PMID 5820999.

- ↑ "Punding on L-dopa". Mov. Disord. 14 (5): 836–8. September 1999. doi:10.1002/1531-8257(199909)14:5<836::AID-MDS1018>3.0.CO;2-0. PMID 10495047.

- ↑ "Hypersexuality--a complication of dopaminergic therapy in Parkinson's disease". Pharmacopsychiatria 16 (4): 107–10. July 1983. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017459. PMID 6685318.

- ↑ "Pathological gambling behaviour: emergence secondary to treatment of Parkinson's disease with dopaminergic agents". Depress Anxiety 11 (4): 185–6. 2000. doi:10.1002/1520-6394(2000)11:4<185::AID-DA8>3.0.CO;2-H. PMID 10945141.

- ↑ "Hedonistic homeostatic dysregulation in patients with Parkinson's disease on dopamine replacement therapies". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 68 (4): 423–8. April 2000. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.4.423. PMID 10727476.

|