Medicine:Pediatric Early Warning Signs

Pediatric Early Warning Signs (PEWS) are clinical manifestations that indicate rapid deterioration in pediatric patients, infancy to adolescence. PEWS Score or PEWS System are objective assessment tools that incorporate the clinical manifestations that have the greatest impact on patient outcome.

Pediatric intensive care is a subspecialty designed for the unique parameters of pediatric patients that need critical care. The first PICU was opened in Europe by Goran Haglund. Over the past few decades, research has proven that adult care and pediatric care vary in parameters, approach, technique, etc. PEWS is used to help determine if a child that is in the Emergency Department should be admitted to the PICU or if a child admitted to the floor should be transferred to the PICU.

It was developed based on the success of MEWS in adult patients to fit the vital parameters and manifestations seen in children. The goal of PEWS is to provide an assessment tool that can be used by multiple specialties and units to objectively determine the overall status of the patient. The purpose of this is to improve communication within teams and across fields, recognition time and patient care, and morbidity and mortality rates. Monaghan created the first PEWS based on MEWS, interviews with pediatric nurses, and observation of pediatric patients.

Currently, multiple PEWS systems are in circulation. They are similar in nature, measuring the same domains, but vary in the parameters used to measure the domains. Therefore, some have been proven more effective than others, however, all of them have been statistically significant in improving patient care times and outcomes.

History of pediatric critical care

Pediatric intensive care has been established as a sub-specialty of medicine over the past two decades. It grew out of a need for increasingly complex pediatric care, long-term management of disease, and advancements in medical and surgical sub-specialties, as well as, life-sustaining therapies.[1] The development of pediatric critical care followed the establishment of pediatric intensive care units or PICUs. The first PICU was opened in Europe by Goran Haglund in 1955 at Children's Hospital of Goteburg in Sweden.[2] Advancements in Neonatology and neonatal intensive care, pediatric general surgery, pediatric cardiac surgery, pediatric anesthesiology lead to its opening because of the need to care for critically ill infants and children. Over the next forty years, hundreds of PICUs were established in academic institutions, children's hospitals, and community hospitals. In 1981, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, SCCM, which express guidelines and standards for adult critical care, recognized pediatric critical care as unique from adults and created a separate section within the SSCM for their care.[2] Other institutes followed throughout the 80's, by 1990 there were multiple training programs, certification available, and sub-board on pediatric critical care.[2] Pediatric critical care is now seen as a multidisciplinary field that includes a team of nurse specialists, respiratory therapists, nutritionists, pharmacists, social workers, physical therapists, occupational therapist, and other medical professionals.[citation needed]

Development of Pediatric Early Warning Score (PEWS)

To reduce the occurrence of second-rate care, improve outcomes, and enhance quality of life, systems to identify adult patients at risk for rapid clinical deterioration were established based on "early warning signs". These signs brought attention to key clinical parameters that, when affected, encouraged emergent intervention. Modified Early Warning System (MEWS) is a tool for nurses to help monitor their patients and improve how quickly a rapidly deteriorating client receives the needed care developed from early warning signs. MEWS helps increase objectivity and communication within hospitals.[3]

Patients with progressing critical illness can be predicted and prevented, but failure to identify the signs and lack of prompt intervention for patients developing acute and critical illness remain a problem. Care for them is challenging because children may be asymptomatic until critically ill. Pediatric patients have unique characteristics and different clinical parameters for each age group; adult parameters and concepts cannot be applied to the pediatric patient. Children have greater compensatory mechanisms than adults and can maintain a normal blood pressure despite considerable loss of fluid. For example, a child with sepsis or severe dehydration may seem unaffected and the acute condition is often identified only by the affected vital parameters.[4] However, their condition deteriorates quickly once compensation mechanisms are overwhelmed. In one review, sixty-one percent of pediatric cardiac arrests were caused by respiratory failure and twenty-nine percent by shock, which are both preventable and potentially reversible causes.[5] Thus, to ensure timely care for pediatric patients and improve outcomes, systemic assessment of key symptoms and their severity is essential.

Early recognition and appropriate intervention are equally important in children and may prevent the need for admission to intensive care. Since children seem relatively unaffected until shortly before respiratory failure and cardiac arrest, Monaghan and a group of associates were interested in developing an early warning score system to help nurses assess pediatric patients objectively and improve mortality rates with timely recognition and treatment. They interviewed staff, reviewed MEWS, and conducted research regarding pediatric clinical conditions and markers used to judge severity. Clinical parameters had to be carefully considered due to the uniqueness of the population. For instance, adult systems use blood pressure as one of the main predictors of decline, however, as described, in children hypotension is considered a late sign of shock and multi-system organ failure. Low blood pressure then is a pre-morbid sign and potentially too late for optimum outcomes.[5] The goal was to create an easy-to-use and impartial system that improved outcomes.

Monaghan and his multidisciplinary team created what is referred to as PEWS, Pediatric Early Warning Signs. Although still in its early years of use, it is now a standard practice in most hospitals and has already shown to identify children who need a higher level of care, decrease code blue incidents, and improve staff communication and patient safety. In other words, children showing signs of clinical decline are assessed by appropriate medical and nursing staff and receive optimum care during their acute episode.[6]

Pediatric assessment

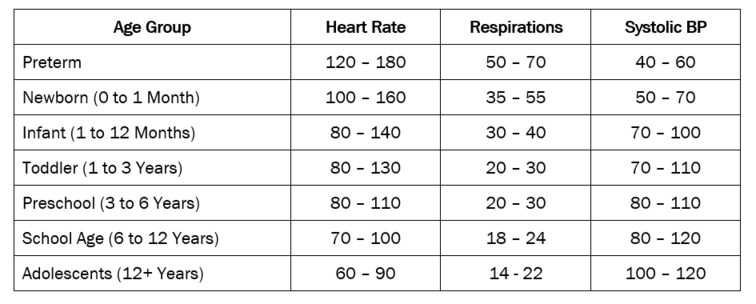

Normal Vital Range

Pediatric patients' -- infancy to adolescence—vital parameters vary by each age group and are different than an adult's healthy range. When reviewing vital signs in each of the age groups, be alert for significant changes and compare with normal values for each of the signs. For best results, when taking vital signs of infants, respirations are counted first before the infant is disturbed, the pulse next, temperature, and then blood pressure last. [citation needed]

Temperature

Temperature should be taken via rectum if the child is under the age of three, for the greatest accuracy, and then orally, unless they are unable to use the oral thermometer properly. Axillary is the least accurate method, but is commonly used when the child is older than three months and the situation is non-concerning or when an accurate oral temperature can't be obtained.[7] Currently, the use of temporal thermometers, that scan the temporal artery, is gaining popularity and is considered accurate for children three months and older.[8]

Heart Rate

There are various pulse sites on the body: the carotid, brachial, radial, femoral, and dorsalis pedis. In children, heart rate is preferably taken apically. To count the rate, place stethoscope on the anterior chest at the fifth intercostal space in a midclavicular position.[8] Each “lub-dub” sound is one beat. It should be taken for one full minute, as well as, determined if the rhythm is regular or irregular.

Respirations

The procedure for measuring a child’s respiratory rate is essentially the same as for an adult. Respiration rate may be taken by observing rise and fall, placing your hand and feeling the rise and fall, or using a stethoscope.[9] Since a child’s respiration rate is diaphragmatic, abdominal movement is observed or felt to count the respirations.[8] Like heart rate, respirations should be counted for one full minute.

Blood Pressure

The size of the blood pressure cuff is determined by the size of the child’s arm or leg. The width of the bladder cuff is two thirds of the length of the long bone of the extremity on which the blood pressure is taken and the length of the bladder cuff should be about three-fourths the circumference and should not overlap.[8] If the bladder of the cuff is too small, the pressure will be falsely high, and if it is too large, falsely low.

Abnormal Findings

Vitals outside of the above parameters are considered abnormal findings. However, before determining additional medical attention is needed, vitals should be repeated to confirm and compared with an individual's baseline assessment. A temperature between 101–102 is considered a mild fever, 102–103 a moderate, and 104 or above a high fever, and delirium or convulsions may occur. From birth until adolescence, temperature between 99.8–100.8 is considered a low-grade fever. If the temperature is taken rectally, it is not considered a fever until it is above 100.4. Once adolescence is reached, it is not considered a fever until 100.4 and if taken rectally, 101.[7] Fever in 3 months and younger is significant and medical referral is needed. Assess the patient to determine if other signs and symptoms are present: flushed face, hot, dry skin, low output, concentrated urine, anorexia, constipation, diarrhea, or vomiting. Older children may complain of sore throat, headaches, aching, and nausea, as well as, other symptoms.[7] Pulse should be checked at distal and proximal sites. Evaluate whether it is normal, bounding, or thready, as well as, compare strength symmetry. Bounding is a stronger than normal pulse and thread a weaker. Unequal pulse is an abnormal finding and indicates a cardiovascular issue.[8] Assess the patient to determine if other signs or symptoms of respiratory – retractions, wheezing, nasal flaring, grunting, etc. -- or cardiac – cyanosis, irritability, edema, etc. -- distress are present. If a child has any acute distress immediate medical intervention is needed.[8]

PEWS models

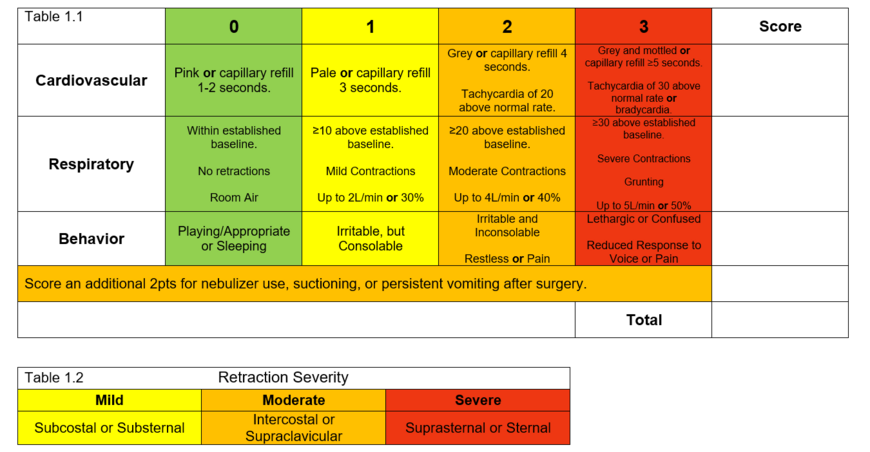

Pediatrician specialists and others who provide care in this field adapted early warning tools from those in practice with adults with the distinct characteristics of the pediatric population; anatomy, physiology, and clinical manifestations are different in pediatric patients than adult. The goal of pediatric early warning systems is to alert staff to deterioration in pediatric patients at the earliest possibility to quickly intervene and improve mortality rates.[10] It is based on the idea that using objective clinical indicators and risk assessment tools will improve communication and improve patient care, however, there is yet to be a standardized model. A variety of PEWS tools exist with multiple parameters, but all models have three domains in common: cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurological.[11]

Domains

The domains in PEWS represent major body systems that are sensitive to changes in the body and thus create the criteria to be evaluated in a patient to help identify if they are at risk for further deterioration. Parameters on how to measure, such as the importance of including blood pressure, temperature, or nebulizer treatments, change with almost each model.[12] The three domains, cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurological, though are consistently seen throughout each model and have been clinically proven to help identify patients in the Emergency Department, ED, who require admission to the PICU, as well as, assess in advance the need to adapt a care plan to avoid rapid response.[13]

Cardiovascular

Heart rate is commonly used in PEWS, as well as, capillary refill. However, only few use blood pressure because it is not considered as reliable of a measure as the other two. As stated previously, children can maintain a stable blood pressure for much longer than adults. Anatomy and physiology is different in infants and children than adults and vary with age, which produces normal ranges for electrocardiograms.[14] Capillary refill is used across the lifespan as a cardiovascular assessment parameter because it is a non-invasive, quick test to help determine blood flow to the tissues. Heart rate is a crucial piece of assessment in acutely ill pediatric patients because bradycardia may be a sign of conductive tissue dysfunction and lead to sudden death.[15]

Respiratory

Methods in determining a patient's needs related to a respiratory system often requires an accurate health history and a thorough physical examination. Respiratory assessment's are done as part of a comprehensive physical examination or as a focused examination. The judgment in determining whether all or part of the history and physical examination is often completed based on a chief complaint of the patient. Respiratory can be measured by rate, rhythm, characteristics of breathing, and supplemental oxygen use. Different characteristics of breathing are lung sounds, retractions, accessory muscle use, tracheal tug, etc. PEWS uses highly visible and easily monitored characteristics are used, such as retractions, that way there is little variation based on in interpretation. Retractions are a sucking in of the skin around the bones of the chest and illustrate the additional use of muscle to breath, indicated the increased work needed to breath. Similarly, the more supplemental oxygen needed, the less the lungs are providing adequate oxygenation. All of these symptoms indicate respiratory failure, a condition where there is inadequate oxygenation to the body's tissues and organs or inadequate removal of carbon monoxide from the body by the lungs. Left untreated, it is life-threatening.[citation needed]

Neurological

Behavior is typically measured by playing, sleeping, irritable, and confused or reduced response to pain.[16] This is due to the fact it is an age-based assessment and pediatric patients have some form of "playing" as their age appropriate norm. Whether it be gurgling and cooing, coloring, or video games, it is age-specific behavior to a younger population. Irritability in children is often a cue that something is wrong, especially in those unable to communicate verbally due to age or disorder.[8] Other scales simply use level of consciousness as they're neurological assessment, instead of behavior.[17]

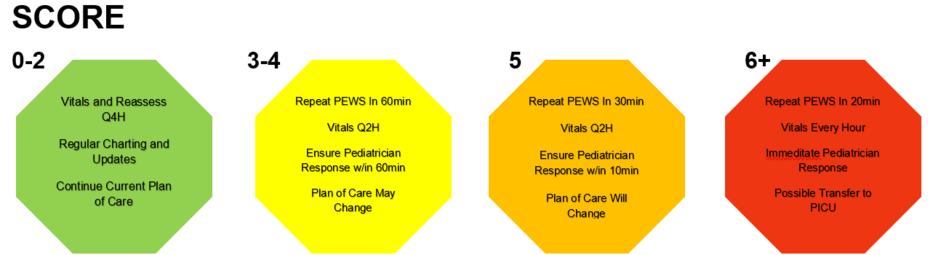

Scoring

Numbers or color are used in scoring of PEWS. The numbers represent the total score added from the domains (pictured in the above table of Monaghan's design) and the colors are easily understandable "cautions" recognized by most people to help facilitate urgency and in some care settings, communication with patients correlated with numeric scores.

0-2: A score of 0-2 indicates no change in a child's status and regular rounding is acceptable. The plan of care will be continued as is.

3-4: Indicates that a child's care is worsening, but they do not need immediate assistance. The plan of care may change or continued close monitoring will be initiated.

5: The child's status is deteriorating and a change in the plan of care is needed to improve outcomes. This is an urgent situation that requires close monitoring and the involvement of other disciplines.

6+: There are severe consequences if quick intervention is not established, including possible permanent damage or death. A child with a PEWS score of 6+ will mostly be transferred to a PICU to receive the level of critical care they need to improve outcomes with a staff trained to do so.

Application in practice

When implemented, PEWS has had statistically significant impact on multiple units and the care of children. It can identify children admitted to the ED who require admission to the PICU, as well as, help staff assessment of their needs and accurate interventions.[13] It has helped identify more than 75% of code blues within one hour of warning and has the ability to assess more than ten hours earlier the need to adapt a care plan to avoid rapid response.[13] Bedside PEWS, an adopted method for bedside care, can help staff identify when a child is at risk for decline and/or rapidly deteriorating.[18] Also, it has proven to improve staff communication and patient safety.[13]

Limitations

One limitation in the use of PEWS is that there is not a standard model in practice. Doctors and nurses have access to too many variations of how to use the PEWS assessment tool and there is no defined standard. There is over 30 different variations of the assessment tool available to the medical staff to help diagnose PEWS.[11] PEWS provides an easy, objective way to measure a deviation from normal, however, with variation in model, the score is not completely transferable.[11] Another limitation is since this is relatively new, there is little research done on the implementation of PEWS and the effectiveness of its usage.

Citations

- ↑ (Epstein and Brill, 2005, p.987)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 (Epstein and Brill, 2005, p.988)

- ↑ "Early Warning Systems: Scorecards That Save Lives" (in en-US). http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/ImprovementStories/EarlyWarningSystemsScorecardsThatSaveLives.aspx.

- ↑ (Jensen, Aagaard, Olesen, and Kirkegaard, 2017, p.2)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 (Monaghan, 2005, p.33)

- ↑ (Monaghan, 2005, p.35)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 (Agrawal, 2009, p.2)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 (Honckenberry and Wilson, 2015)

- ↑ (Agrawal, 2009, p.1)

- ↑ (Murray, Williams, Pignatarao, and Volpe, 2015, p.166; Fuijkschot et al., 2015, p.15)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 (Murray, Williams, Pignataro, and Volpe, 2015, p.171)

- ↑ (Murray, Williams, Pignataro, and Volpe, 2015, p.171; Jensen, Aagaard, Olesen, and Kirkegaard, 2017, p.2)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 (Murray, Williams, Pignataro, and Volpe, 2015, p.168-170)

- ↑ (Baruteau et al., 2016, p.151)

- ↑ (Baruteau et al., 2016, p.152)

- ↑ (Murray, Williams, Pignataro, and Volpe, 2015, p.170)

- ↑ (Jensen, Aagaard, Olesen, and Kirkegaard, 2017, p.3)

- ↑ (Arke et al., 2010, p.e767)

References

- Agrawal, S. (2009). Normal vital signs in children: heart rate, respirations, temperature, and blood pressure. Complex Child E-Magazine, 1-4.

- Akre, M., Frinkelstein, M., Erickson, M., Liu, M., Vanderbilt, L., and Billman, G. (2010). Sensitivity of the pediatric early warning score to identify patient deterioration. Pediatrics, 125(4), e763-e769. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0338

- Baruteau, A., Perry, J. C., Sanatani, S., Horie, M., and Dubin, A. M. (2016). Evaluation and management of bradycardia in neonates and children. European Journal of Pediatrics, 175, 151-161. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2689-z

- Epstein, D. and Brill, J. E. (2005). A history of pediatric critical care of medicine. Pediatric Research, 58(5), 987-996. doi: 0031-3998/05/5805-0987

- Hockenberry, M. and Wilson, D. (2015). Wong’s nursing care of infants and children (10th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, Mosby.

- Jensen, C. S., Aagaard, H., Olesen, H. V., and Kirkegaard, H. (2017). A multicenter, randomized intervention study of the paediatric early warning score: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 18(267), 1-9. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2011-7

- Fuijkschot, J., Verhout, B., Lemson, J., Draaisma, M. T., and Loeffen, L. C. (2015). Validation of a paediatric early warning score: first results and implications of usage. European Journal of Pediatrics, 174, 15-21. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2357-8

- Monaghan, A. (2005). Detecting and managing deterioration in children. Paediatric Nursing, 17(1), 32-35.

- Murray, J. S., Williams, L. A., Pignataro, S., and Volpe, D. (2015). An integrative review of pediatric early warning system scores. Pediatric Nursing, 41(4), 165-174.

- Parshuram, C. S., Dryden-Palmer, K., Farrell, C., Gottesman, R., Gray, M., Hutchison, J. S., Helfaer, M., Hunt, E., Joffee, A., Lacroix, J., Nadkarni, V., Parkin, P, Wensley, D., and Willan, A. R. (2015). Evaluating processes of care and outcomes of children in hospital (EPOCH): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 16(245), 1-12. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0712-3