Medicine:SLC35A1-CDG

| SLC35A1-CDG | |

|---|---|

| Other names | CDG IIf, CONGENITAL DISORDER OF GLYCOSYLATION, TYPE IIf, CDG2F, CDG syndrome type IIf, CMP-sialic acid transporter deficiency, Carbohydrate deficient glycoprotein syndrome type IIf, Congenital disorder of glycosylation type 2f, Congenital disorder of glycosylation type IIf, CDG-IIf, SLC35A1-CDG[1] |

| |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

| Symptoms | Vascular system abnormalities |

| Complications | Early death |

| Usual onset | Birth-Childhood |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Genetic mutation |

| Prevention | none |

| Prognosis | Medium - Poor |

| Frequency | very rare, only 3 cases have been described in medical literature |

| Deaths | out of the 3 people diagnosed with this condition, 1 is suspected to still be alive, the other 2 died due to surgical complications that were aggravated by their condition. |

SLC35A1-CDG is a rare inherited disorder that mainly affects the vascular systems of the body.[2] It forms part of a large group of disorders called congenital disorders of glycosylation.[3][4] It is caused by mutations in the SLC35A1 gene, located in the sixth chromosome.

Signs and symptoms

The following list comprises the symptoms of this condition (as listed by the HPO):[5]

- Increased susceptibility to bleeding

- Structural abnormalities of the megakaryocytes

- Platelet granule anomalies

- Cellulitis

- Giant platelets (platelets larger than 7 micrometers)

- Low oxygen level in blood

- Neutropenia

- Pneumonia

- Longer time for injured areas on the skin to stop bleeding

- Pulmonary hemorrhage

- Respiratory distress

- Increased susceptibility of getting bruises

- Thrombocytopenia

Complications

There are various complications associated with this condition, all of which are associated with the symptoms listed above.

For example, the hypoxemia (decreased blood oxygen level) can result in hypoxia which will affect the heart and brain more severely if left untreated.[6]

Diagnosis

This condition can be diagnosed by doing whole genome sequencing and by physical examination.

Genetics

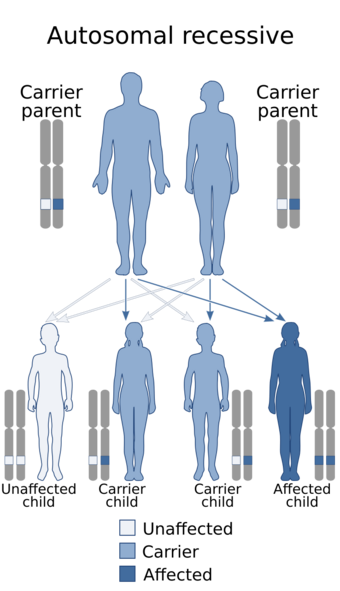

Like the name implies, this condition is caused by mutations in the SLC35A1 gene, located in the long arm of the sixth chromosome.[7] These mutations are inherited following an autosomal recessive manner, meaning that only people who are homozygous for the gene mutation are going to show the traits associated with it.[8]

Treatment

Treatment is symptom-focused:

- Cellulitis can be treated with prescribed oral antibiotics.[9]

- Hypoxemia can be treated with methods such as the use of oxygen tanks.[6]

- Pneumonia treatment varies depending on the severity of said affliction, but generally, mild pneumonia can be treated with antibiotics, drinking liquids regularly, and by taking a rest. Other treatment methods include the use of pain-killers for reducing pain and fever which typically accompany pneumonia cases.[10]

- Pulmonary hemorrhage treatment varies depending on whether or not it's localized, but in these cases (localized bleeding) methods such as bronchostopic therapy and surgery can help treat it.[11]

- Respiratory distress treatment aims for the cause, but generally supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation machines, and medication can help treat it.[12]

Prevalence

Like other congenital disorders of glycosylation, this condition is extremely rare, with (according to OMIM) only 3 un-related patients described in medical literature to date.[13] (August 2022)

Cases

The following list comprises the only 3 cases of SLC35A1 ever reported in history (according to the OMIM page for the condition: #603585 CONGENITAL DISORDER OF GLYCOSYLATION, TYPE IIf; CDG2F)[13]

- 2001: Willig et al. describes the first case of SLC35A1-CDG in medical history, a 4 month old male child who suffered from a spontaneous bleeding incident in the posterior chamber of his right eye which occurred alongside cutaneous hemorrhages, further laboratory studies revealed thrombocytopenia and neutropenia. In the next 30 months (2 years and 6 months) of his life, he suffered from high amounts of episodic multi-systemic bleeding, with one of these episodes including a severe pulmonary hemorrhage. The child also suffered from frequent recurrent bacterial infections, he later died from complications of a bone marrow transparent when he was 37 months (3 years, 1 month) old.[14] In 2005, Martinez-Duncker et al. found two compound heterozygous missense mutations in the SLC35A1 gene of said child, out of those two mutations, one was a pathogenic truncating mutation, while the other was a common single-nucleotide polymorphism.[15]

- 2013: Mohamed et al. describes the case of a 22-year old woman who was the child of consanguineous parents of Turkish origin. She started developing paychomotor delays and generalized tonic-clonic seizures at the age of 7 (even though she was normally developing before this age), and she then developed behavioural problems during puberty. She had microcephaly, a mild case of ataxia, decreased reflexes of the lower distal extremities, hypotonia, intellectual disability, a systolic cardiac murmur associated with aortic insufficiency, hypotelorism, flat occiput, deep-set eyes, shortened philtrum, webbed neck, clinodactyly of the fingers, bunions on both feet, and joint hypermobility by the time she was 20. Further laboratory studies showed macrothrombocytopenia, proteinuria, amino aciduria, and decreased amounts of coagulation factors. She perished when she was 22 years old because of post-surgery complications. Genetic testing of said woman revealed a homozygous missense mutation on the SLC35A1 gene, when genetic testing was performed on her parents, it was revealed that they were heterozygous carriers of the mutation. In vitro functional expression studies showed that this mutation (named Q101H) lead to CMP-Sia transport activity that was reduced by 50% compared to healthy control subjects. Mammalian cells that were deficient of SLC35A1 (due to the Q101H mutation) showed polysialic acid expression restoration that was reduced by 15% compared to the wild type version of the gene.[16]

- 2017: Ng et al. describes a 12 year old girl of German descent, said child was born hypotonic and developed seizures alongside oro-facial tics at the age of 4 months. EEGs from a medically induced partial seizure revealed focal spikes alongside polyspikes. She had severe encephalopathy, severe psychomotor delays, and moderate intellectual disability (she had an IQ of less than 55), speech difficulties, ataxic-dyskinetic movements. Other features included nystagmus and autistic-like symptoms. Laboratory studies showed a serum transferrin CDG type II pattern and a combined defect in N- and O-glycosylation. After the use of whole exome sequencing, she was found to have compound heterozygous missense mutations (which were later termed as T156R and E196K) in the SLC35A1 gene, said mutations were confirmed by doing Sanger sequencing. Studies done on the cells of the child showed lowered amounts of N- and O-glycans which ended up as sialic acid alongside a severe loss of SLC35A1 transport function.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ "SLC35A1-CDG (CDG-IIf)". https://rarediseases.org/gard-rare-disease/slc35a1-cdg-cdg-iif/.

- ↑ RESERVADOS, INSERM US14-- TODOS LOS DERECHOS. "Orphanet: SLC35A1 CDG" (in es). https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?lng=ES&Expert=238459.

- ↑ "SLC35A1-CDG (CDG-IIf) | CDG Hub" (in en). https://www.cdghub.com/cdg/slc35a1-cdg-cdg-iif/.

- ↑ "KEGG DISEASE: Congenital disorders of glycosylation type II". https://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/www_bget?ds:H00119.

- ↑ "SLC35A1-CDG (CDG-IIf) - About the Disease - Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center" (in en). https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/12409/slc35a1-cdg-cdg-iif.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Hypoxemia: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment". https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17727-hypoxemia.

- ↑ "SLC35A1 Gene - GeneCards | S35A1 Protein | S35A1 Antibody". https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=SLC35A1.

- ↑ "Entry - *605634 - SOLUTE CARRIER FAMILY 35 (CMP-SIALIC ACID TRANSPORTER), MEMBER 1; SLC35A1 - OMIM" (in en-us). https://www.omim.org/entry/605634#0003.

- ↑ "Cellulitis - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cellulitis/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20370766.

- ↑ "Pneumonia - Treatment" (in en). 2017-10-23. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pneumonia/treatment/.

- ↑ Ficker, J. H.; Brückl, W. M.; Suc, J.; Geise, A. (2017-03-01). "[Haemoptysis : Intensive care management of pulmonary hemorrhage"]. Der Internist 58 (3): 218–225. doi:10.1007/s00108-017-0190-7. ISSN 1432-1289. PMID 28138763. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28138763/#:~:text=Localized%20pulmonary%20bleeding%20usually%20requires,medical%20treatment%20of%20coagulation%20disorders..

- ↑ "ARDS - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ards/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20355581.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Entry - #603585 - CONGENITAL DISORDER OF GLYCOSYLATION, TYPE IIf; CDG2F - OMIM" (in en-us). https://www.omim.org/entry/603585.

- ↑ Willig, T. B.; Breton-Gorius, J.; Elbim, C.; Mignotte, V.; Kaplan, C.; Mollicone, R.; Pasquier, C.; Filipe, A. et al. (2001-02-01). "Macrothrombocytopenia with abnormal demarcation membranes in megakaryocytes and neutropenia with a complete lack of sialyl-Lewis-X antigen in leukocytes--a new syndrome?". Blood 97 (3): 826–828. doi:10.1182/blood.v97.3.826. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 11157507. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11157507/.

- ↑ Martinez-Duncker, Ivan; Dupré, Thierry; Piller, Véronique; Piller, Friedrich; Candelier, Jean-Jacques; Trichet, Catherine; Tchernia, Gil; Oriol, Rafael et al. (2005-04-01). "Genetic complementation reveals a novel human congenital disorder of glycosylation of type II, due to inactivation of the Golgi CMP-sialic acid transporter". Blood 105 (7): 2671–2676. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-09-3509. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 15576474. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15576474/.

- ↑ Mohamed, Miski; Ashikov, Angel; Guillard, Mailys; Robben, Joris H.; Schmidt, Samuel; van den Heuvel, B.; de Brouwer, Arjan P. M.; Gerardy-Schahn, Rita et al. (2013-08-13). "Intellectual disability and bleeding diathesis due to deficient CMP--sialic acid transport". Neurology 81 (7): 681–687. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a08f53. ISSN 1526-632X. PMID 23873973. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23873973/.

- ↑ Ng, Bobby G.; Asteggiano, Carla G.; Kircher, Martin; Buckingham, Kati J.; Raymond, Kimiyo; Nickerson, Deborah A.; Shendure, Jay; Bamshad, Michael J. et al. (2017-11-01). "Encephalopathy caused by novel mutations in the CMP-sialic acid transporter, SLC35A1". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A 173 (11): 2906–2911. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.38412. ISSN 1552-4833. PMID 28856833.

|