Medicine:Scleral reinforcement surgery

| Scleral reinforcement surgery | |

|---|---|

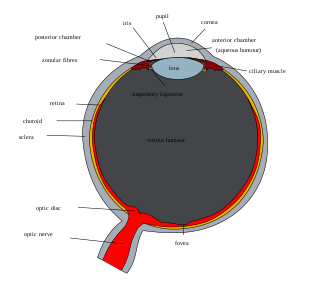

Schematic diagram of the human eye. (Sclera labeled on left.) | |

| Specialty | ophthalmology |

Scleral reinforcement is a surgical procedure used to reduce or stop further macular damage caused by high myopia, which can be degenerative.

High myopia

Myopia is one of the leading causes of blindness in the world.[1][2] It is caused by both genetic [3] and environmental factors,[4] such as mechanical stretching, excessive eye work and accommodation, as well as an elevated intraocular pressure. It affects both children and adults. In many cases, myopia will stabilize once the growth process has been completed, but in more severe chronic cases, loss of vision can occur.

Degenerative myopia, also known as malignant, pathological, or progressive myopia, is characterized by posterior sclera elongation and thinning (at least 25.5 mm to 26.5 mm) and high refractive errors of at least -5 to -7.5 diopters with an increase per year.[1] There may also be changes in the fundus, including posterior staphyloma, caused by the eye growing posteriorly and losing its spherical shape.[2] Since enlargement of the eye does not progress at a uniform rate, abnormal protrusions of uveal tissue may occur through weak points in the eye. Staphyloma is marked by a thinning of sclera collagen bundles and decreased number of collagen striations. It correlates with a large posterior temporal bulge. Curtin described five varieties, based on size, shape, and change in appearance of the optic nerve and retinal vessels, but the posterior pole type is the most common.[5] As the posterior staphyloma enlarges, choroidal tissue becomes thin and Bruch's membrane begins to break, creating lesions called lacquer cracks. Neovascularization may occur, causing blood vessels to protrude through the cracks and leak in the space underneath the photoreceptor cell layer. This hemorrhaging can lead to scarring and macular degeneration, causing vision to gradually deteriorate.[2] If left untreated, high myopia can cause retinal detachment, glaucoma, and a higher risk of cataracts.

History

The condition of posterior staphyloma in high myopia was first described by Scarpa in the 1800s.[6] Speculation about reinforcement of the eye began in the 19th century, when Rubin noted that sclera reinforcement “is probably the only one of all the surgical techniques [for myopia] which attempts to correct a cause, rather than an effect”.[7] Procedures in early literature aimed at shortening the length of the eyeball by resecting a ring of sclera from the equator of the eye.[2] Later procedures focused on modifying the axial length of the eye, by preventing elongation and staphyloma progression by placing grafts over the posterior part of the eye. In 1930, Shevelev proposed the idea of transplantation of fascia lata for sclera reinforcement.[8] Curtin promoted the use of donor-sclera grafting for reinforcement.[9] In 1976, Momose first introduced Lyodura, a material derived from processed cadaver dura mater.[10] At this point, many different surgeons made alterations to existing techniques. Snyder and Thompson modified reinforcement techniques and had positive outcomes,[11] while others, like Curtin and Whitmore, expressed dissatisfaction with their negative conclusions.[12]

Purpose

The surgery aims to cover the thinning posterior pole with a supportive material to withstand intraocular pressure and prevent further progression of the posterior staphyloma. The strain is reduced, although damage from the pathological process cannot be reversed. By stopping the progression of the disease, vision may be maintained or improved.

Methods of surgery

There are three basic techniques, referred to as X-shaped, Y-shaped, and single strip support.[10] In X-shaped and Y-shaped, the arms run the risk of the being pulled medially, which would press on the optic nerve and could result in optic nerve atrophy. In single strip support, the material covers the posterior pole vertically between the optic nerve and insertion of the inferior oblique muscle. Often, this method is preferred, since it is the easiest method for placement, provides the widest area of support, and reduces the risk of optic nerve interference.[2]

Materials

Many different materials have been used in the past, including fascia lata,[8] Lyodura (lyophilized human dura),[10] Gore-Tex,[2] Zenoderm (porcine skin dermis),[13] animal tendons, and donor's or cadaver’s sclera.[9][14][15] Human sclera is thought to offer the best support, as well as Lyodura, which is biologically compatible with the eyeball and has sufficient tensile strength. Artificial materials, such as nylon or silicone, are not suggested.[10][clarification needed] Sclera from cadaver’s or animal tendons run the risk of being rejected.

Procedure

While there have been many modifications, Thompson’s procedure has often been used as a basis.[16] First, the conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule are incised about 6 mm from the corneal limbus. The lateral, superior, and inferior recti muscles are separated using a strabismus hook. The connecting tissue is then separated from the posterior pole, as well as the inferior oblique muscle. The strip of material is passed under the separated muscles, and pushed down deeply towards the posterior pole. Both ends of the material strip are crossed over the medial rectus muscle and sutured to the sclera on the medial side of the superior and inferior recti muscles. The conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule are then closed together.

Complications

Long-term complication rates are usually low, but short-term complications may include chemosis, choroidal edema or hemorrhage, damage to the vortex vein, and transient motility problems.[16]

Controversy

Scleral reinforcement surgery is not presently popular in the United States, and there has been a scarcity of published clinical studies. Donor sclera material is also difficult to acquire and store, and artificial materials are still being tested. This procedure is much more popular in other countries, such as the former Soviet Union and Japan.[2] There is also controversy regarding in what developmental stage this procedure should be performed.[2] Some feel efforts should be made as soon as possible to arrest progression in children. Others feel that the procedure should only be done in cases where high myopia is indicated with macular changes. Furthermore, different surgeons have particular criteria that must be met by patients in order to receive surgery.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Grossniklaus, H.E. and W.R. Green, Pathologic findings in pathologic myopia. Retina, 1992. 12(2): p. 127-33.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Bores, L.D., Scleral Reinforcement, in Refractive Eye Surgery. 2001, Blackwell Science, Inc.: USA. p. 466-491.

- ↑ Curtin, B.J., The nature of pathological myopia, in The Myopias. 1985, Harper & Row: Philadelphia. p. 237-239.

- ↑ Saw, S., et al., Myopia: gene-environment interaction. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 2000. 29(3): p. 290.

- ↑ Curtin, B.J., The posterior staphyloma of pathologic myopia. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc, 1977. 75: p. 67-86.

- ↑ Scarpa, A. A. (1818). A Treatise on the Principal Diseases of the Eye. London.

- ↑ Rubin, M.L., Surgical procedures available for influencing refractive error., in Refractive Anomalies of the Eye. 1966, US Government Printing Office: Washington.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Shevelev, M.M., Operation against high myopia and scleralectasia with aid of the transplantation of fascia lata on thinned sclera. Russian Oftalmol J, 1930. 11(1): p. 107-110.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Curtin, B.J., Surgical support of the posterior sclera: Part II. Clinical results. Am J Ophthalmol, 1961. 52: p. 253.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Momose, A., Surgical treatment of myopia.... with special references to posterior scleral support operation and radial keratotomy. Vol. 31. 1983. 759-767.

- ↑ Snyder, A. and F. Thompson, A simplified technique for surgical treatment of degenerative myopia. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 1972. 74(2): p. 273.

- ↑ Curtin, B. and W. Whitmore, Long-term results of scleral reinforcement surgery. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 1987. 103(4): p. 544.

- ↑ Gerinec, A., & Slezakova, G. (2001). Posterior scleroplasty in children with severe myopia. Bratisl Lek Listy, 102(2), 73-78.

- ↑ Balashova, N., Ghaffariyeh, A., & Honarpisheh, N. (2010). Scleroplasty in progressive myopia. Eye.

- ↑ Ward, B., Tarutta, E., & Mayer, M. (2009). The efficacy and safety of posterior pole buckles in the control of progressive high myopia. Eye, 23(12), 2169-2174.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Thompson, F., Scleral Reinforcement. Chapter 10., in Myopia Surgery. 1990, Macmillan: New York. p. 267-297.

|