Medicine:Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis

| Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Carpometacarpal (CMC) osteoarthritis (OA) of the thumb, osteoarthritis at the base of the thumb, basilar (or basal) joint arthritis,[1] rhizarthrosis [2] |

| |

| Osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint | |

| Specialty | Plastic surgery |

Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis (TMC OA) is, also known as osteoarthritis at the base of the thumb, thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis, basilar (or basal) joint arthritis, or as rhizarthrosis.[3][1][2] This joint is formed by the trapezium bone of the wrist and the metacarpal bone of the thumb. This is one of the joints where most humans develop osteoarthritis with age.[4] Osteoarthritis is age-related loss of the smooth surface of the bone where it moves against another bone (cartilage of the joint).[3][5] In reaction to the loss of cartilage, the bones thicken at the joint surface, resulting in subchondral sclerosis. Also, bony outgrowths, called osteophytes (also known as “bone spurs”), are formed at the joint margins.[6]

The main symptom is pain, particularly with gripping and pinching.[7][8] This pain is often described as weakness, but true weakness is not a part of this disease. People may also note a change in shape of the thumb.[7][8] Some people choose surgery, but most people find they can accommodate trapeziometacarpal arthrthis.[9][10][11]

Signs and symptoms

The symptom that brings people with TMC OA to the doctor is pain.[8] Pain is typically experienced with gripping and pinching. People experiencing pain may describe it as weakness.

There may be enlargement at the TMC joint.[8] This area may be tender, meaning it is painful when pressed. There may also be hyperextension of the metacarpophalangeal joint. The thumb metacarpal deviates towards the middle of the hand (adduction).[12] Also a grinding sound, known as crepitus, can be heard when the TMC joint is moved, more so when axial pressure is applied.[13]

Etiology and Epidemiology

TMC OA is an expected part of aging in men and women equally.[4] A population-based study of radiographic signs of pathophysiology in 3595 people assessed in a research-related comprehensive health examination found no association with physical workload.[9] A study of people seeing a hand specialist for symptoms unrelated to TMC OA demonstrated no relationship of radiographic TMC OA to hand activity.[14]

Studies that compare people presenting with TMC symptoms to people without symptoms are sometimes interpreted as indicating that activities can contribute to the development of TMC OA.[15] A more accurate conclusion may be that hand use is associated with seeking care for symptoms related to TMC OA. Ligamentous laxity is often associated with TMC OA, but this is based on rationale rather than experimental evidence.[16] Obesity may be related to TMC OA.[9]

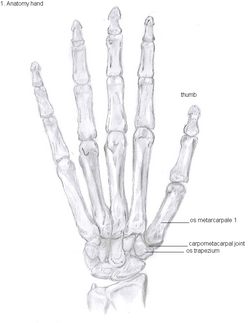

Anatomy

The TMC joint is a synovial joint between the trapezium bone of the wrist and the metacarpal bone at the base of the thumb. This joint is a so-called saddle joint (articulatio sellaris), unlike the CMC joints of the other four fingers which are ellipsoid joints.[17] This means that the surfaces of the TMC joint are both concave and convex.

This shape provides the TMC joint a wide range of motion. Movements include:[18]

- Flexion

- Extension

- Abduction

- Adduction

- Opposition

- Reposition

- Circumduction

The TMC joint is stabilized by 16 ligaments.[19] Of these ligaments, the deep anterior oblique ligament, also known as the palmar beak ligament, is considered to be the most important stabilizing ligament.[20]

Diagnosis

TMC OA is diagnosed based on symptoms and signs.[8] Radiographs can confirm the diagnosis and the severity of TMC OA. Other diagnoses in this region include scaphotrapezial trapezoid arthritis and first dorsal compartment tendinopathy (De Quervain syndrome) although these are usually easy to distinguish.

Classification

TMC OA severity was classified by Eaton and Littler which can be simplified as follows:[21][22]

Stage 1:

- slight widening of the joint space

- < 1/3 subluxation of the joint (in any projection)

Stage 2:

- Osteophytes, < 2 mm in diameter, are present. (usually adjacent to the volar or dorsal facets of the trapezium)

Stage 3:

- Osteophytes, > 2 mm in diameter, are present (usually adjacent to the volar and dorsal facets of the trapezium)

- Slight joint space narrowing

Stage 4:

- Narrow joint space

- Concomitant scaphotrapezial arthritis

A simpler classification is no arthritis, some arthritis, and severe arthritis.[23] This simpler classification system omits the potentially contradictory details of the Eaton/Littler classification and keeps scaphotrapezial arthrosis separate.

Treatment

There are no treatments proved to slow or relieve TMC OA. In other words, there are no disease-modifying treatments. All treatments are symptom alleviating (palliative). Most surgery is reconstructive—it removes the TMC joint. Metacarpal osteotomy was proposed as a potentially disease modifying surgery for more limited arthrosis,[24] but there is no experimental support for this theory.[25]

There is limited and limited quality evidence regarding splints, corticosteroid injections, manual therapy and other palliative measures. Studies with adequate randomization, blinding, and independent assessment are lacking.

Arthrodesis fuses the TMC joint. It is uncommonly used.[26] Arthroplasty surgery for TMC OA removes part or all of the trapezium.[27] Surgery may also support the metacarpal by reconstructing a ligament using a tendon graft or weave. Surgery may also place something in the space where the trapeziometacarpal joint was, either a tendon wrapped up into a ball or a prosthesis.

The best available evidence suggests no difference in symptom alleviation with these variations of TMC arthroplasty.[28]

In one randomized trial comparing trapeziectomy alone with trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction and trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition, patients evaluated 5 to 18 years after surgery had similar pain intensity, grip strength and key and tip pinch strengths after each procedure.[29] Trapeziectomy alone is associated with fewer complications than the other procedures.

Trapeziectomy

During trapeziectomy,[30] the trapezium bone is removed without any further surgical adjustments.The trapezium bone is removed through an approximately three centimeter long incision along the lateral side of the thumb. To preserve surrounding structures, the trapezium bone is removed "by splitting" it into pieces.

An empty gap is left by the trapeziectomy and the wound is closed with sutures. Despite this gap, no significant changes in function of the thumb are reported.[27] After the surgery, the thumb will be immobilized with a cast.

Trapeziectomy with Tendon Interposition

Some physicians still believe that it is better to fill the gap left by the trapeziectomy. They assume that filling the gap with a part of a tendon is preferable in terms of function, stability and position of the thumb. This is based on the assumption that interposition can help maintain the space between the metacarpal and the scaphoid, which will improve comfort and capability. Neither of these assumptions is supported by experimental evidence.

During trapeziectomy with TI, a longitudinal strip of the palmaris longus tendon is collected. [31] If this tendon is absent (which is the case in 13% of the population), half of the flexor carpi radialis tendon (FCR) can be used.

The tendon is then formed into a circular shape and placed in the gap, where it is stabilized by sutures.[12]

Trapeziectomy with Ligament Reconstruction

Another technique is used to reconstruct the volar beak ligament after trapeziectomy. The rationale is that ligament reconstruction(LR) helps maintain the gap between the metacarpal and the scaphoid, and that a larger gap is associated with greater comfort and capability.[32] Again these possibilities are not supported by experimental evidence.

During this procedure the anterior oblique ligament is reconstructed using the FCR tendon. There is a wide variety in techniques to perform this LR, but they all have a similar goal.

Trapeziectomy with LRTI

Some physicians believe that combining LR with TI will help maintain gap between the metacarpal and the scaphoid.[33] And that doing so will improve comfort and capability. Keep in mind that these aspects of the rationale are not supported by experimental evidence. The evidence suggests that all of these procedures have comparable long-term results.

Arthrodesis

Arthrodesis of the TMC joint is a surgical procedure in which the trapezium bone and the metacarpal bone of the thumb are secured together. They are held together by K-wires or a plate and screws until the bone will heal.

Disadvantages include inability to flatten the hand.[27] Additionally, the stress on the CMC joint is now spread over the adjacent joints, those joints are more likely to develop osteoarthritis.[34]

Nevertheless, this procedure can be used in patients with stage II and III CMC OA as well as in young people with posttraumatic osteoarthritis.[27]

Joint Replacement

The joint can be replaced with artificial material. An artificial joint is also referred to as a prosthesis. Prostheses are more problematic at the trapeziometacarpal joint compared joints like the knee or the hips.

[27]Prostheses come in many varieties, such as spacers or resurfacing prostheses.

It’s not clear within the current literature that a prosthesis has any advantage over trapeziectomy.[27]

Overall, joint replacements are related to long-term complications such as subluxation, fractures, synovitis (due to the material used) and nerve damaging.[35] In many cases revision surgery is needed to either remove or repair the prosthesis. Also note that usage of a joint replacement is heavy in costs.

The quality of the prostheses is improving and there is reason to believe this will have a positive effect on outcome in the years to follow.[27]

Metacarpal osteotomy

The aim of metacarpal osteotomy is to change the pressure distribution on the TMC joint. The hope is that this will slow the pace of development of osteoarthritis. There is no evidence that this procedure can modify the natural course of TMC OA. Osteotomy may be considered for people with mild arthritis.[24]

During osteotomy, the metacarpal is cut and a wedge shape bone fragment is removed to move the bone away from the hand.[36] Postoperative, the thumb of the patient is immobilized using a thumb-cast.

Possible complications are non-union of the bone, persistent pain related to unrecognized CMC or pantrapezial disease and radial sensory nerve injury.[24]

Complications

The most common complication after surgery is pain persisting in the thumb. Over long term, there is pain relief, but on short term, patients experience pain from the surgery itself. The main complaint is a burning sensation or hypersensitivity over the incision. Some patients develop a complex regional pain syndrome. This is a syndrome of chronic pain with changes of temperature and colour of the skin.

Other general complications include superficial radial nerve damage and postoperative wound infection.

After arthrodesis, non-union, in which fusion of the trapezium bone with the metacarpal bone fails, occurs in 8% to 21% of the cases.[27]

Subluxation of a prosthesis is a complication where the prosthesis is mobile and is partially dislocated. When the prosthesis is fully dislocated it is called a luxation. Both are painful and need revision surgery so the prosthesis can be repaired or removed.[37] When using a prosthesis over a longer period of time, there is a chance of breaking the prosthesis itself. This is due to mechanical wear.

Prostheses might also cause a reaction of the body against the artificial material they are made of, resulting in local inflammation.

Epidemiology

CMC OA is the most common form of OA affecting the hand.[38] Dahaghin et al. showed that about 15% of women and 7% of men between 50 and 60 years of age develop CMC OA of the thumb.[39] However, in about 65% of people older than 55 years, radiologic evidence of OA was present without any symptoms.[39] Armstrong et al. reported a prevalence of 33% in postmenopausal women, of which one third was symptomatic, compared to 11% in men older than 55 years.[38] This shows CMC OA of the thumb is significantly more prevalent in women, especially in postmenopausal women, compared to men.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Patel, Tejas J.; Beredjiklian, Pedro K.; Matzon, Jonas L. (2012-12-16). "Trapeziometacarpal joint arthritis". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 6 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1007/s12178-012-9147-6. ISSN 1935-973X. PMID 23242976.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 TACCARDO, GIUSEPPE; DE VITIS, ROCCO; PARRONE, GIUSEPPE; MILANO, GIUSEPPE; FANFANI, FRANCESCO (2014-01-08). "Surgical treatment of trapeziometacarpal joint osteoarthritis". Joints 1 (3): 138–144. ISSN 2512-9090. PMID 25606524.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint: the pathophysiology of articular cartilage degeneration. II. Articular wear patterns in the osteoarthritic joint". J Hand Surg Am 16 (6): 975–82. November 1991. doi:10.1016/S0363-5023(10)80055-3. PMID 1748768.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Becker, Stéphanie J. E.; Briet, Jan Paul; Hageman, Michiel G. J. S.; Ring, David (December 2013). "Death, taxes, and trapeziometacarpal arthrosis". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 471 (12): 3738–3744. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3243-9. ISSN 1528-1132. PMID 23959907.

- ↑ "[Anatomical study of the normal and degenerative articular surfaces on the first carpometacarpal joint]" (in ja). Nippon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi 66 (4): 228–39. April 1992. PMID 1593195.

- ↑ "Degenerative joint disease of the trapezium: a comparative radiographic and anatomic study". J Hand Surg Am 8 (2): 160–6. March 1983. doi:10.1016/s0363-5023(83)80008-2. PMID 6833724.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Burton R. I. (1973). "Basal joint arthrosis of the thumb". Orthop. Clin. North Am. 4 (347): 331–8. doi:10.1016/S0030-5898(20)30797-5. PMID 4707436.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Clinical assessment of the thumb trapeziometacarpal joint". Hand Clin 17 (2): 185–95. May 2001. doi:10.1016/S0749-0712(21)00239-0. PMID 11478041.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Haara, Mikko M.; Heliövaara, Markku; Kröger, Heikki; Arokoski, Jari P. A.; Manninen, Pirjo; Kärkkäinen, Alpo; Knekt, Paul; Impivaara, Olli et al. (July 2004). "Osteoarthritis in the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. Prevalence and associations with disability and mortality". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume 86 (7): 1452–1457. doi:10.2106/00004623-200407000-00013. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 15252092. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15252092/.

- ↑ Wilkens, Suzanne C.; Ring, David; Teunis, Teun; Lee, Sang-Gil P.; Chen, Neal C. (March 2019). "Decision Aid for Trapeziometacarpal Arthritis: A Randomized Controlled Trial". The Journal of Hand Surgery 44 (3): 247.e1–247.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.06.004. ISSN 1531-6564. PMID 30031600. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30031600/.

- ↑ Becker, Stéphanie J. E.; Teunis, Teun; Blauth, Johann; Kortlever, Joost T. P.; Dyer, George S. M.; Ring, David (March 2015). "Medical services and associated costs vary widely among surgeons treating patients with hand osteoarthritis". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 473 (3): 1111–1117. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3912-3. ISSN 1528-1132. PMID 25171936.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Thumb trapeziometacarpal arthritis: treatment with ligament reconstruction tendon interposition arthroplasty". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 117 (6): 116e–128e. May 2006. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000214652.31293.23. PMID 16651933.

- ↑ Carr M. M., Freiberg A. (1994). "Osteoarthritis of the thumb: Clinical aspects and management". Am. Fam. Physician 50 (995): 995–1000. PMID 7942418.

- ↑ Wilkens, Suzanne C.; Tarabochia, Matthew A.; Ring, David; Chen, Neal C. (May 2019). "Factors Associated With Radiographic Trapeziometacarpal Arthrosis in Patients Not Seeking Care for This Condition". Hand (New York, N.Y.) 14 (3): 364–370. doi:10.1177/1558944717732064. ISSN 1558-9447. PMID 28918660.

- ↑ Fontana, Luc; Neel, Stéphanie; Claise, Jean-Marc; Ughetto, Sylvie; Catilina, Pierre (April 2007). "Osteoarthritis of the thumb carpometacarpal joint in women and occupational risk factors: a case-control study". The Journal of Hand Surgery 32 (4): 459–465. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.01.014. ISSN 0363-5023. PMID 17398355. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17398355/.

- ↑ "Histopathology of the palmar beak ligament in trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis". J Hand Surg Am 24 (3): 496–504. May 1999. doi:10.1053/jhsu.1999.0496. PMID 10357527.

- ↑ Sobotta Anatomy, 14th ed., Elsevier, ISBN:9780702034831

- ↑ Gray's Anatomy for Students, second edition, Elsevier, ISBN:9780443069529

- ↑ "An anatomic study of the stabilizing ligaments of the trapezium and trapeziometacarpal joint". J Hand Surg Am 24 (4): 786–798. 1999. doi:10.1053/jhsu.1999.0786. PMID 10447171.

- ↑ "Contact patterns in the trapeziometacarpal joint: the role of the palmar beak ligament". J Hand Surg Am 18 (2): 238–44. March 1993. doi:10.1016/0363-5023(93)90354-6. PMID 8463587.

- ↑ Tomaino, M. M. Thumb basal joint arthritis. In D. P. Green et al. (Eds.), Green's Operative Hand Surgery, 5th Ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2005. Pp. 461–485.

- ↑ "Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Staging as a rationale for treatment". Hand Clin 3 (4): 455–71. November 1987. doi:10.1016/S0749-0712(21)00761-7. PMID 3693416.

- ↑ Sodha, Samir; Ring, David; Zurakowski, David; Jupiter, Jesse B. (December 2005). "Prevalence of osteoarthrosis of the trapeziometacarpal joint". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume 87 (12): 2614–2618. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00104. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 16322609. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16322609/.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "Osteotomy versus tendon arthroplasty in trapeziometacarpal arthrosis: 17 patients followed for 1 year". Acta Orthop Scand 69 (3): 287–90. June 1998. doi:10.3109/17453679809000932. PMID 9703405.

- ↑ Bachoura, Abdo; Yakish, Eric J.; Lubahn, John D. (August 2018). "Survival and Long-Term Outcomes of Thumb Metacarpal Extension Osteotomy for Symptomatic Carpometacarpal Laxity and Early Basal Joint Arthritis". The Journal of Hand Surgery 43 (8): 772.e1–772.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.01.005. ISSN 1531-6564. PMID 29503049.

- ↑ Wolf, Jennifer Moriatis; Delaronde, Steven (January 2012). "Current trends in nonoperative and operative treatment of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a survey of US hand surgeons". The Journal of Hand Surgery 37 (1): 77–82. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.10.010. ISSN 1531-6564. PMID 22119601. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22119601/.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 27.7 Vermeulen, Guus M.; Slijper, Harm; Feitz, Reinier; Hovius, Steven E.R.; Moojen, Thybout M.; Selles, Ruud W. (2011). "Surgical Management of Primary Thumb Carpometacarpal Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review". The Journal of Hand Surgery 36 (1): 157–169. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.10.028. ISSN 0363-5023. PMID 21193136.

- ↑ Wajon, Anne; Vinycomb, Toby; Carr, Emma; Edmunds, Ian; Ada, Louise (2015-02-23). "Surgery for thumb (trapeziometacarpal joint) osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 (2): CD004631. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004631.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25702783.

- ↑ "Five- to 18-year follow-up for treatment of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a prospective comparison of excision, tendon interposition, and ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition". J Hand Surg Am 37 (3): 411–7. March 2012. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.11.027. PMID 22305824.

- ↑ Gervis W.H. (1949). "Excision of the trapezium for osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint". J Bone Joint Surg 31B (4): 537–539. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.31B4.537. PMID 15397137.

- ↑ Weilby A (1988). "Tendon interposition arthroplasty of the first carpo-metacarpal joint". J Hand Surg Br 13 (4): 421–425. doi:10.1016/0266-7681(88)90171-4. PMID 3249143.

- ↑ Blank J, Feldon P (1997). "Thumb metacarpophalangeal joint stabilization during carpometacarpal joint surgery". Atlas Hand Clin 2: 217–225.

- ↑ "Surgical management of basal joint arthritis of the thumb. Part II. Ligament reconstruction with tendon interposition arthroplasty". J Hand Surg Am 11 (3): 324–32. May 1986. doi:10.1016/s0363-5023(86)80137-x. PMID 3711604.

- ↑ "Tendon interposition arthroplasty versus arthrodesis for the treatment of trapeziometacarpal arthritis: a retrospective comparative follow-up study". J Hand Surg Am 26 (5): 869–76. September 2001. doi:10.1053/jhsu.2001.26659. PMID 11561240.

- ↑ Wajon, Anne, ed (February 2015). "Surgery for thumb (trapeziometacarpal joint) osteoarthritis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015 (2): CD004631. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004631.pub4. PMID 25702783. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004631.pub5. If this is an intentional citation to a retracted paper, please replace

{{Retracted}}with{{Retracted|intentional=yes}}.) - ↑ "First metacarpal osteotomy for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis". J Bone Joint Surg Br 80 (3): 508–12. May 1998. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.80b3.8199. PMID 9619947.

- ↑ "Results following removal of silicone trapezium metacarpal implants". J Hand Surg Am 3 (2): 154–6. March 1978. doi:10.1016/s0363-5023(78)80064-1. PMID 632545.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "The prevalence of reparative arthritis of the base of the thumb in post-menopausal women". J Hand Surg 19B (3): 340–341. 1994. doi:10.1016/0266-7681(94)90085-X. PMID 8077824.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Prevalence and pattern of radiographic hand osteoarthritis and association with pain and disability (the Rotterdam study)". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64 (5): 682–7. May 2005. doi:10.1136/ard.2004.023564. PMID 15374852.

|