Morrie's law

Morrie's law is a special trigonometric identity. Its name is due to the physicist Richard Feynman, who used to refer to the identity under that name. Feynman picked that name because he learned it during his childhood from a boy with the name Morrie Jacobs and afterwards remembered it for all of his life.[1]

Identity and generalisation

- [math]\displaystyle{ \cos(20^\circ) \cdot \cos(40^\circ) \cdot \cos(80^\circ) = \frac{1}{8}. }[/math]

It is a special case of the more general identity

- [math]\displaystyle{ 2^n \cdot \prod_{k=0}^{n-1} \cos(2^k \alpha) = \frac{\sin(2^n \alpha)}{\sin(\alpha)} }[/math]

with n = 3 and α = 20° and the fact that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\sin(160^\circ)}{\sin(20^\circ)} = \frac{\sin(180^\circ-20^\circ)}{\sin(20^\circ)} = 1, }[/math]

since

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sin(180^\circ-x) = \sin(x). }[/math]

Similar identities

A similar identity for the sine function also holds:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sin(20^\circ) \cdot \sin(40^\circ) \cdot \sin(80^\circ) = \frac{\sqrt 3}{8}. }[/math]

Moreover, dividing the second identity by the first, the following identity is evident:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tan(20^\circ) \cdot \tan(40^\circ) \cdot \tan(80^\circ) = \sqrt 3 = \tan(60^\circ). }[/math]

Proof

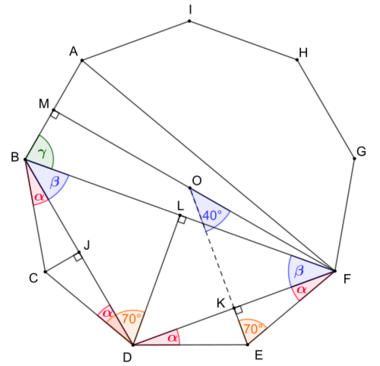

Geometric proof of Morrie's law

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} 40^\circ&=\frac{360^\circ}{9} \\70^\circ&=\frac{180^\circ-40^\circ}{2}\\ \alpha&=180^\circ-90^\circ-70^\circ =20^\circ \\ \beta&=180^\circ -90^\circ-(70^\circ-\alpha)=40^\circ \\ \gamma&=140^\circ -\beta -\alpha=80^\circ \end{align} }[/math]

Consider a regular nonagon [math]\displaystyle{ ABCDEFGHI }[/math] with side length [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] and let [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] be the midpoint of [math]\displaystyle{ AB }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] the midpoint [math]\displaystyle{ BF }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ J }[/math] the midpoint of [math]\displaystyle{ BD }[/math]. The inner angles of the nonagon equal [math]\displaystyle{ 140^\circ }[/math] and furthermore [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma=\angle FBM=80^\circ }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \beta=\angle DBF=40^\circ }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha=\angle CBD=20^\circ }[/math] (see graphic). Applying the cosinus definition in the right angle triangles [math]\displaystyle{ \triangle BFM }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \triangle BDL }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \triangle BCJ }[/math] then yields the proof for Morrie's law:[2]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} 1&=|AB|\\ &=2\cdot|MB|\\ &=2\cdot|BF|\cdot\cos(\gamma)\\ &=2^2|BL|\cos(\gamma)\\ &=2^2\cdot|BD|\cdot\cos(\gamma)\cdot\cos(\beta)\\ &=2^3\cdot|BJ|\cdot\cos(\gamma)\cdot\cos(\beta) \\ &=2^3\cdot|BC|\cdot\cos(\gamma)\cdot\cos(\beta)\cdot\cos(\alpha) \\ &=2^3\cdot 1 \cdot\cos(\gamma)\cdot\cos(\beta)\cdot\cos(\alpha) \\ &=8\cdot\cos(80^\circ)\cdot\cos(40^\circ)\cdot\cos(20^\circ) \end{align} }[/math]

Algebraic proof of the generalised identity

Recall the double angle formula for the sine function

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sin(2 \alpha) = 2 \sin(\alpha) \cos(\alpha). }[/math]

Solve for [math]\displaystyle{ \cos(\alpha) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \cos(\alpha)=\frac{\sin(2 \alpha)}{2 \sin(\alpha)}. }[/math]

It follows that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \cos(2 \alpha) & = \frac{\sin(4 \alpha)}{2 \sin(2 \alpha)} \\[6pt] \cos(4 \alpha) & = \frac{\sin(8 \alpha)}{2 \sin(4 \alpha)} \\ & \,\,\,\vdots \\ \cos\left(2^{n-1} \alpha\right) & = \frac{\sin\left(2^n \alpha\right)}{2 \sin\left(2^{n-1} \alpha\right)}. \end{align} }[/math]

Multiplying all of these expressions together yields:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \cos(\alpha) \cos(2 \alpha) \cos(4 \alpha) \cdots \cos\left(2^{n-1} \alpha\right) = \frac{\sin(2 \alpha)}{2 \sin(\alpha)} \cdot \frac{\sin(4 \alpha)}{2 \sin(2 \alpha)} \cdot \frac{\sin(8 \alpha)}{2 \sin(4 \alpha)} \cdots \frac{\sin\left(2^n \alpha\right)}{2 \sin\left(2^{n-1} \alpha\right)}. }[/math]

The intermediate numerators and denominators cancel leaving only the first denominator, a power of 2 and the final numerator. Note that there are n terms in both sides of the expression. Thus,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \prod_{k=0}^{n-1} \cos\left(2^k \alpha\right) = \frac{\sin\left(2^n \alpha\right)}{2^n \sin(\alpha)}, }[/math]

which is equivalent to the generalization of Morrie's law.

References

- ↑ W. A. Beyer, J. D. Louck, and D. Zeilberger, A Generalization of a Curiosity that Feynman Remembered All His Life, Math. Mag. 69, 43–44, 1996. (JSTOR)

- ↑ Samuel G. Moreno, Esther M. García-Caballero: "'A Geometric Proof of Morrie's Law". In: American Mathematical Monthly, vol. 122, no. 2 (February 2015), p. 168 (JSTOR)

Further reading

- Glen Van Brummelen: Trigonometry: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2020, ISBN:9780192545466, pp. 79–83

- Ernest C. Anderson: Morrie's Law and Experimental Mathematics. In: Journal of recreational mathematics, 1998

External links

|