Moser–de Bruijn sequence

In number theory, the Moser–de Bruijn sequence is an integer sequence named after Leo Moser and Nicolaas Govert de Bruijn, consisting of the sums of distinct powers of 4. Equivalently, they are the numbers whose binary representations are nonzero only in even positions.

The Moser–de Bruijn numbers in this sequence grow in proportion to the square numbers. They are the squares for a modified form of arithmetic without carrying. The difference of two Moser–de Bruijn numbers, multiplied by two, is never square. Every natural number can be formed in a unique way as the sum of a Moser–de Bruijn number and twice a Moser–de Bruijn number. This representation as a sum defines a one-to-one correspondence between integers and pairs of integers, listed in order of their positions on a Z-order curve.

The Moser–de Bruijn sequence can be used to construct pairs of transcendental numbers that are multiplicative inverses of each other and both have simple decimal representations. A simple recurrence relation allows values of the Moser–de Bruijn sequence to be calculated from earlier values, and can be used to prove that the Moser–de Bruijn sequence is a 2-regular sequence.

Definition and examples

The numbers in the Moser–de Bruijn sequence are formed by adding distinct powers of four. The sequence lists these numbers in sorted order; it begins[1]

For instance, 69 belongs to this sequence because it equals 64 + 4 + 1, a sum of three distinct powers of 4.

Another definition of the Moser–de Bruijn sequence is that it is the ordered sequence of numbers whose binary representation has nonzero digits only in the even positions. For instance, 69 belongs to the sequence, because its binary representation 10001012 has nonzero digits in the positions for 26, 22, and 20, all of which have even exponents. The numbers in the sequence can also be described as the numbers whose base-4 representation uses only the digits 0 or 1.[1] For a number in this sequence, the base-4 representation can be found from the binary representation by skipping the binary digits in odd positions, which should all be zero. The hexadecimal representation of these numbers contains only the digits 0, 1, 4, 5. For instance, 69 = 10114 = 4516. Equivalently, they are the numbers whose binary and negabinary representations are equal.[1][2] Because there are no two consecutive nonzeros in their binary representations, the Moser–de Bruijn sequence forms a subsequence of the fibbinary numbers.

Growth rate and differences

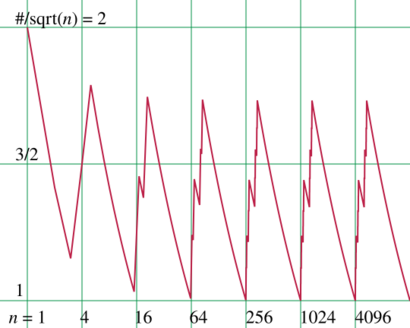

It follows from either the binary or base-4 definitions of these numbers that they grow roughly in proportion to the square numbers. The number of elements in the Moser–de Bruijn sequence that are below any given threshold [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] is proportional to [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt n }[/math],[3] a fact which is also true of the square numbers. More precisely, the number oscillates between [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt n }[/math] (for numbers of the form [math]\displaystyle{ n=4^k }[/math]) and [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{3n} }[/math] (for [math]\displaystyle{ n\sim4^k/3 }[/math]). In fact the numbers in the Moser–de Bruijn sequence are the squares for a version of arithmetic without carrying on binary numbers, in which the addition and multiplication of single bits are respectively the exclusive or and logical conjunction operations.[4]

In connection with the Furstenberg–Sárközy theorem on sequences of numbers with no square difference, Imre Z. Ruzsa found a construction for large square-difference-free sets that, like the binary definition of the Moser–de Bruijn sequence, restricts the digits in alternating positions in the base-[math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] numbers.[5] When applied to the base [math]\displaystyle{ b=2 }[/math], Ruzsa's construction generates the Moser–de Bruijn sequence multiplied by two, a set that is again square-difference-free. However, this set is too sparse to provide nontrivial lower bounds for the Furstenberg–Sárközy theorem.

Unique representation as sums

The Moser–de Bruijn sequence obeys a property similar to that of a Sidon sequence: the sums [math]\displaystyle{ x+2y }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] both belong to the Moser–de Bruijn sequence, are all unique. No two of these sums have the same value. Moreover, every integer [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] can be represented as a sum [math]\displaystyle{ x+2y }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] both belong to the Moser–de Bruijn sequence. To find the sum that represents [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math], compute [math]\displaystyle{ x=n\ \&\ \mathrm{0x55555555} }[/math], the bitwise Boolean and of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] with a binary value (expressed here in hexadecimal) that has ones in all of its even positions, and set [math]\displaystyle{ y=(n-x)/2 }[/math].[1][6]

The Moser–de Bruijn sequence is the only sequence with this property, that all integers have a unique expression as [math]\displaystyle{ x+2y }[/math]. It is for this reason that the sequence was originally studied by (Moser 1962).[7] Extending the property, (De Bruijn 1964) found infinitely many other linear expressions like [math]\displaystyle{ x+2y }[/math] that, when [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] both belong to the Moser–de Bruijn sequence, uniquely represent all integers.[8][9]

Z-order curve and successor formula

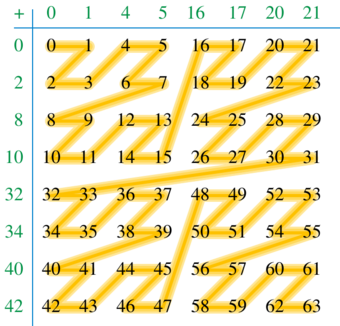

Decomposing a number [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] into [math]\displaystyle{ n=x+2y }[/math], and then applying to [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] an order-preserving map from the Moser–de Bruijn sequence to the integers (by replacing the powers of four in each number by the corresponding powers of two) gives a bijection from non-negative integers to ordered pairs of non-negative integers. The inverse of this bijection gives a linear ordering on the points in the plane with non-negative integer coordinates, which may be used to define the Z-order curve.[1][10]

In connection with this application, it is convenient to have a formula to generate each successive element of the Moser–de Bruijn sequence from its predecessor. This can be done as follows. If [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] is an element of the sequence, then the next member after [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] can be obtained by filling in the bits in odd positions of the binary representation of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] by ones, adding one to the result, and then masking off the filled-in bits. Filling the bits and adding one can be combined into a single addition operation. That is, the next member is the number given by the formula[1][6][10] [math]\displaystyle{ \displaystyle (x + \textrm{0xaaaaaaab})\ \&\ \textrm{0x55555555}. }[/math] The two hexadecimal constants appearing in this formula can be interpreted as the 2-adic numbers [math]\displaystyle{ 1/3 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ -1/3 }[/math], respectively.[1]

Subtraction game

(Golomb 1966) investigated a subtraction game, analogous to subtract a square, based on this sequence. In Golomb's game, two players take turns removing coins from a pile of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] coins. In each move, a player may remove any number of coins that belongs to the Moser–de Bruijn sequence. Removing any other number of coins is not allowed. The winner is the player who removes the last coin. As Golomb observes, the "cold" positions of this game (the ones in which the player who is about to move is losing) are exactly the positions of the form [math]\displaystyle{ 2y }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] belongs to the Moser–de Bruijn sequence. A winning strategy for playing this game is to decompose the current number of coins, [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math], into [math]\displaystyle{ x+2y }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] both belong to the Moser–de Bruijn sequence, and then (if [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] is nonzero) to remove [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] coins, leaving a cold position to the other player. If [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] is zero, this strategy is not possible, and there is no winning move.[3]

Decimal reciprocals

The Moser–de Bruijn sequence forms the basis of an example of an irrational number [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] with the unusual property that the decimal representations of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ 1/x }[/math] can both be written simply and explicitly. Let [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] denote the Moser–de Bruijn sequence itself. Then for [math]\displaystyle{ x = 3\sum_{n\in E} 10^{-n} = 3.300330000000000330033\dots, }[/math] a decimal number whose nonzero digits are in the positions given by the Moser–de Bruijn sequence, it follows that the nonzero digits of its reciprocal are located in positions 1, 3, 9, 11, ..., given by doubling the numbers in [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] and adding one to all of them:[11][12] [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{x}=3\sum_{n\in E} 10^{-2n-1} = 0.30300000303\dots\ . }[/math]

Alternatively, one can write: [math]\displaystyle{ \displaystyle\left(\sum_{n\in E}10^{-n}\right)\left(\sum_{n\in E}10^{-2n}\right)=\frac{10}{9}. }[/math]

Similar examples also work in other bases. For instance, the two binary numbers whose nonzero bits are in the same positions as the nonzero digits of the two decimal numbers above are also irrational reciprocals.[13] These binary and decimal numbers, and the numbers defined in the same way for any other base by repeating a single nonzero digit in the positions given by the Moser–de Bruijn sequence, are transcendental numbers. Their transcendence can be proven from the fact that the long strings of zeros in their digits allow them to be approximated more accurately by rational numbers than would be allowed by Roth's theorem if they were algebraic numbers, having irrationality measure no less than 3.[12]

Generating function

The generating function [math]\displaystyle{ F(x)=\prod_{i=0}^{\infty}(1+x^{4^i})=1+x+x^4+x^5+x^{16}+x^{17}+\cdots, }[/math] whose exponents in the expanded form are given by the Moser–de Bruijn sequence, obeys the functional equations[1][2] [math]\displaystyle{ F(x)F(x^2)=\frac{1}{1-x} }[/math] and[14] [math]\displaystyle{ F(x)=(1+x)F(x^4). }[/math] For example, this function can be used to describe the two decimal reciprocals given above: one is [math]\displaystyle{ 3 F(1/10) }[/math] and the other is [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac{3}{10} F(1/100) }[/math]. The fact that they are reciprocals is an instance of the first of the two functional equations. The partial products of the product form of the generating function can be used to generate the convergents of the continued fraction expansion of these numbers themselves, as well as multiples of them.[11]

Recurrence and regularity

The Moser–de Bruijn sequence obeys a recurrence relation that allows the nth value of the sequence, [math]\displaystyle{ S(n) }[/math] (starting at [math]\displaystyle{ S(0)=0 }[/math]) to be determined from the value at position [math]\displaystyle{ \lfloor n/2\rfloor }[/math]: [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S(2n)&=4S(n)\\ S(2n+1)&=4S(n)+1 \end{align} }[/math] Iterating this recurrence allows any subsequence of the form [math]\displaystyle{ S(2^i n + j) }[/math] to be expressed as a linear function of the original sequence, meaning that the Moser–de Bruijn sequence is a 2-regular sequence.[15]

See also

- Stanley sequence and Cantor set, sets defined similarly using the base-3 representations of their elements

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Sloane, N. J. A., ed. "Sequence A000695 (Moser–De Bruijn sequence)". OEIS Foundation. https://oeis.org/A000695.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Arndt, Jörg (2011), Matters Computational: Ideas, Algorithms, Source Code, Springer, pp. 59, 750, http://jjj.de/fxt/fxtbook.pdf.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "A mathematical investigation of games of "take-away"", Journal of Combinatorial Theory 1 (4): 443–458, 1966, doi:10.1016/S0021-9800(66)80016-9.

- ↑ "Dismal arithmetic", Journal of Integer Sequences 14 (9): Article 11.9.8, 34, 2011, Bibcode: 2011arXiv1107.1130A, http://emis.de/journals/JIS/VOL14/Sloane/carry2.pdf.

- ↑ "Difference sets without squares", Periodica Mathematica Hungarica 15 (3): 205–209, 1984, doi:10.1007/BF02454169.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The constants in this formula are expressed in hexadecimal and based on a 32-bit word size. The same bit pattern should be extended or reduced in the obvious way to handle other word sizes.

- ↑ "An application of generating series", Mathematics Magazine 35 (1): 37–38, 1962, doi:10.1080/0025570X.1962.11975291.

- ↑ "Some direct decompositions of the set of integers", Mathematics of Computation 18 (88): 537–546, 1964, doi:10.2307/2002940.

- ↑ Eigen, S. J.; Ito, Y.; Prasad, V. S. (2004), "Universally bad integers and the 2-adics", Journal of Number Theory 107 (2): 322–334, doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2004.04.001.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Thiyagalingam, Jeyarajan; Beckmann, Olav; Kelly, Paul H. J. (September 2006), "Is Morton layout competitive for large two-dimensional arrays yet?", Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 18 (11): 1509–1539, doi:10.1002/cpe.v18:11, http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~ob3/Publications/CandCPEMorton2004.pdf, retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Continued fractions of formal power series", Advances in number theory (Kingston, ON, 1991), Oxford Sci. Publ., Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 1993, pp. 453–466, http://web.williams.edu/Mathematics/sjmiller/public_html/book/papers/vdp/Poorten_ContFracsOfFormalPowerSeries.pdf.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Blanchard, André; Mendès France, Michel (1982), "Symétrie et transcendance", Bulletin des Sciences Mathématiques 106 (3): 325–335. As cited by (van der Poorten 1993).

- ↑ "On the binary expansions of algebraic numbers", Journal de Théorie des Nombres de Bordeaux 16 (3): 487–518, 2004, doi:10.5802/jtnb.457, http://jtnb.cedram.org/item?id=JTNB_2004__16_3_487_0. See in particular the discussion following Theorem 4.2.

- ↑ "Integers with digits 0 or 1", Mathematics of Computation 46 (174): 683–689, 1986, doi:10.2307/2008006.

- ↑ Allouche, Jean-Paul (1992), "The ring of k-regular sequences", Theoretical Computer Science 98 (2): 163–197, doi:10.1016/0304-3975(92)90001-V. Example 13, p. 188.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Moser–De Bruijn Sequence". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Moser-deBruijnSequence.html.

|