Organization:Mobile Military Health Formation

| Mobile Military Health Formation | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | |

| Branch | South African Military Health Service |

| Type | Special Operations |

| Part of | SANDF |

| Headquarters | Pretoria, Gauteng |

| Nickname(s) | Mobile |

| Patron | St. Michael the Archangel |

| Motto(s) | Fidelis et Fortis |

| Engagements | Ango-Boer War, World War I, World War II, South African Border War, Battle of Bangui |

| Decorations | SAMHS Sword of Peace |

| Website | https://www.mhs.mil.za |

| Commanders | |

| Surgeon General | Lt Gen Ntshavheni Peter Maphaha |

| General Officer Commanding | Brig Gen K.S. Masipa |

The South African Military Health Service Mobile Military Health Formation is the SANDF military special operations health capability. The formation operates two regular force medical battalions, with 7 Medical Battalion Group[1] providing support to the South African Special Forces Brigade and 8 Medical Battalion Group focusing on airborne operations. Three reserve units, 1 Medical Battalion Group, 3 Medical Battalion Group and 6 Medical Battalion Group fall under the command of the formation.

The formation specialises in various types of operations including emergency medicine, disaster response, medical rescue, hostage negotiation and CBRNE warfare defence.

Similar to most special operations units, the Mobile Military Health Formation has a high attrition rate with most candidates failing to meet the strict physical and academic requirements.

The Mobile Military Health Formation's current structure[2] is the result of extensive restructuring [3] that occurred during the transition to democracy[4] in South Africa [5] and military reforms from the Defence Review 1998.[6] Through its designation as the SAMHS primary force preparation entity,[7] the formation has a broad mandate to ensure the delivery of comprehensive medical health services[8] to the SANDF during conventional operations. In light of recent advancements in warfare[9][10] and the ongoing threat of global terrorism,[11][12] the SANDF recognised a need to shift attention towards more mobile and adaptable military operations, specifically with a focus on disaster response.[13][14] The SAMHS has adapted its approach to healthcare delivery in tandem with other SANDF services and divisions.

History

The history [15] of the Mobile Military Health Formation dates back to the Boer Wars[16][17] with ambulance detachments of the Natal Volunteer Medical Corps (NVMC), the Volunteer Staff Corps in the Cape Colony, and the Transvaal Volunteer Staff Corps.

The Corps played a notable role in the Anglo-Boer War, the Rand Strikes, and World War I. In 1939, they were granted the honour of wearing the Mackenzie Tartan. During World War II, the unit formed part of 10 and 11 Field Ambulances [18] and saw service in the Western Desert and Italy.

As of July 1, 1979, the South African Medical Corps (SAMC),[19] previously a part of the Army, transitioned to become the South African Medical Service (SAMS), which became the fourth arm of the South African Defence Force (SADF). During the military exercise Ex Jumbo in 1980, the formation of 11 Medical Battalion tested the newly developed Medical Battalion concept, which involved combining all field ambulances.

1 Field Ambulance merged with 17 Field Ambulance to become 1 Medical Battalion Group in November 1981. The first special operations medical unit, 7 Medical Battalion Group, was conceptualised in the early 1980s when the South African Defence Force was involved in various unconventional operations such as Project Barnacle and Project Coast.

8 Mobile Hospital was disbanded on 5 November 1981, when the majority of the serving and active members were incorporated into 6 Medical Battalion Group. Subsequently, all existing Medical Battalion Groups were re-constituted and re-formed to create the Mobile Medical Brigade’s five Medical Battalion Groups in September 1992.

The disbandment of 8 Mobile Hospital occurred on November 5, 1981, with most of the serving and active members being integrated into 6 Medical Battalion Group. Following this, the South African Medical Service formed five Medical Battalion Groups in September 1992 by re-establishing and re-forming existing Medical Battalion Groups.

The Defence Review 2015 emphasised the need for the SANDF to maintain a core Rapid Deployment capability that will consist of Special Forces and Special Operations Forces. While the Defence Review was later criticised for being difficult to implement[20] due to funding concerns,[21] the SANDF has confirmed its commitment to reform into a lighter mobile force[22] with response capacity for domestic and international operations.

As a result, the SAMHS reviewed its own organisation in order for it to be well established to provide optimal health support for the future defence force. In early 2023 the Surgeon General approved a restructuring of the Mobile Military Health Formation to better underscore its status as the ready multidisciplinary rapid deployment health capability[23] of the SANDF.[24]

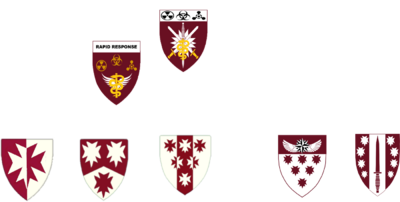

Structure

The Mobile Military Health Formation headquarters consists of command element under a Brigadier General, brigade staff (S1 - S9), and a disaster response/ CBRNE defence Rapid Response Group.

The formation has three subordinate multi-role reserve Battalion Groups and two special operations Battalion Groups.

Reserve Battalions

1 Medical Battalion Group

3 Medical Battalion Group

6 Medical Battalion Group

Regular Force Battalions

7 Medical Battalion Group (South African Special Forces Multidisciplinary Health Support)

8 Medical Battalion Group (South African Army Airborne Force Multidisciplinary Health Support)

World Wars

World War I

The Natal Medical Corps (Hospital London, 1904) was activated in 1914 and served in the South West African Campaign.[25] During this time, they established the 6th Stationary Hospital in Swakupmond and operated the hospital ship 'Ebani'. Another group from the corps participated in the battle for Gideon against German forces. When the SWA Campaign ended, the Field Ambulance joined the 1st Infantry Brigade and travelled on the HMS Kenilworth Castle from Cape Town to receive training at the Royal Army Medical Corps[26] Twezeldown on October 10, 1915.[27] After completing their training, the unit was transported to Egypt on the HMT Corsican and arrived in Alexandria on January 13, 1916.

As part of the Natal Corps of the 1st South African Field Ambulance, the unit actively participated in significant battles such as the Somme, Deville Wood, Ypres, and the Menin Road.

World War II

During the war,[28] the medical units were combined and given new unit numbers starting from 10. The members of the 1st Field Ambulance became the main personnel of the newly formed 10 and 11 Field Ambulances, distinguishing themselves by wearing the Mackenzie Tartan behind their cap badges. These two units provided medical support in the Western Desert and Italy. Another unit, 17 Field Ambulance, was formed during the war and served alongside Australian forces, but unfortunately, it was captured when Tobruk fell in 1942. After the war, the Field Ambulances returned to their original numbering system.

Domestic Operations

During the Civil Disturbances [29] in June 1913 and 1914, 1 Field Ambulance Transvaal (later known as 6 Medical Battalion Group) was mobilised to provide first aid. They operated from the Drill Hall in Johannesburg and later set up a 50-bed hospital in the Wanderers Club building in the same city.

During the Rand Strikes of 1922,[30] the Natal Medical Corps was mobilized alongside other Natal Regiments and deployed to the gold Reef.

Operation DUIKER and Operation LETABA

In 1959/60, Ops DUIKER saw the mobilization of 1 Medical Battalion Group in response to the Cato Manor Riots.[31] Then, during Ops LETABA in 1961 which took place in Voortrekkerhoogte, helicopters were utilized for the first time to evacuate casualties. This marked a significant milestone as members of 1st Field Ambulance were informed that they were at the cutting edge of modern warfare.

Operation JAMBU

Mobile military Health Formation units deployed during Operation JAMBU [32] (stability operations during South Africa’s first democratic election[33] over the period 15 April to 15 May 1994. All medical task teams were responsible for providing medical support to the elements of the SA Army.

Operation BATA

In 2007, during a long civil service strike,[34] the SAMHS was requested to manage hospitals and other public facilities (known as Operation BATA). The Mobile Military Health Formation was responsible for carrying out the operation. As a recognition of their efforts, the participants of the SAMHS were bestowed with the Tshumelo Ikatelaho medal, which was given to all those involved in this operation.

Operation CHARIOT

Mobile Military Health Formation units deployed forces in support of the SANDF and SAPS during the internal unrest [35] in South Africa and provided medical support during the unrest of July 2021.

South African Border War

In the late 1970s, the 17 Field Ambulance [36] performed Border duties and provided support for conventional operations in Angola.[37] The members of 1st Field Ambulance were assigned patrol duties along the Mozambique border in Northern Natal. In 1978, they were fully deployed to test the new Field Ambulance system [38] in Thabazimbi.

7 Medical Battalion Group offered support to the Parachute Battalions[39] operating in Angola and on the South West Africa (Namibia) Border. Throughout the latter stages of the war, the unit played a role in nearly all major operations. During Operation MODULER, Operation HOOPER, and Operation PACKER, it provided support to its various allocated units, regardless of their deployment locations during the conflict.

Wouter Basson, the founder of 7 Medical Battalion Group, was also assigned the responsibility of providing a defensive CBRNE advisory role in some operations.

United Nations Peacekeeping Missions

The Mobile Military Health Formation has been providing support to the South African National Defence Force in its peacekeeping efforts across Africa in recent years. Its main responsibility is to mobilise SAMHS elements and capabilities for UN Peacekeeping Missions. It served as the rear headquarters for SAMHS members deployed on those missions. Notable recent deployments include Operation Fibre in Burundi and Operation Mistral in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Mobile Military Health Formation units were also involved in the SANDF deployment as part of the Force Intervention Brigade to the DRC from 2014.

SADC Missions

Operation BOLEAS

Operation Boleas, a military operation led by South Africa and sanctioned by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), was conducted to restore stability in Lesotho after a coup d'état. The operation commenced on September 22, 1998,[40] at dawn. The medical support for the task force, consisting of around 700 troops from various units like 1 Special Service Battalion, 1 South African Infantry Battalion (Motorised), 1 Parachute Battalion, a pathfinder platoon of 44 Parachute Regiment, and a battalion of the Botswana Defence Force, was provided by 15 to 20 Ops medics and doctors from 7 Medical Battalion Group.

Two members of the unit were killed[41] during intense combat at Katse Dam on September 22, 1998.

SAMIM

Due to the ongoing instability in Cabo Delgado, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has decided that a multinational intervention is required. South Africa has offered its support to the SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM), with the involvement of the South African National Defence Force's special operations units, such as the SA Special Forces and 7 Medical Battalion Group. Additionally, 8 Medical Battalion Group is providing assistance to the landward Combat Teams.[42]

Battle of Bangui

Over the period of March 22, 2013, to March 24, 2013, soldiers from 7 Medical Battalion Group were involved in the Battle of Bangui[43] in the Central African Republic. Military experts have referred to this battle as one of the most challenging engagements for the South African National Defence Force,[44] in recent years. The South African paratroopers, consisting of around 200 troops, supported by a small number of Special Forces, were attacked on the outskirts of Bangui by an estimated rebel force of 3,000 individuals. 13 South African paratroopers were killed during this conflict, with an additional 27 sustaining injuries. The rebels suffered significant losses, estimated to be over 800 casualties. As a result of their bravery, members of the 7 Medical Battalion Group[45] were honoured with various medals.

Honours

In 1935, the Natal Medical Corps changed its name to 1st Field Ambulance and later became known as 1 Medical Battalion Group. In 1939, after receiving approval from various authorities, including the British War Office and the Surgeon General, the unit was allowed to wear the Mackenzie Tartan. This recognition was achieved through the efforts of Colonel G.D. English, with the support of The Countess of Cromach and the Seaforth Highlanders.

On July 6, 1979, 1 Field Ambulance was granted the Freedom of the City of Durban, an esteemed honour. That same year, the unit also served as the Guard of Honour for the inaugural Durban Military Tattoo.

On October 23, 2010, 3 Medical Battalion Group was granted the privilege of freedom of entry into Cape Town. The Volunteer Medical Staff Corps, which preceded this unit, received the King's Colours from King Edward VII for their valuable services during the Anglo-Boer War from 1899-1902. This recognition distinguished them as the only non-combat unit in South Africa to be honoured by the British monarchy in this way.

Additionally, 7 Medical Battalion Group and 8 Medical Battalion Group received battle honours for their involvement in the Battle of Bangui and their participation in United Nations Peacekeeping operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. SANDF unit combat actions in the DRC from 2014, have contributed significantly to the neutralisation of the M23 rebel group.

References

- ↑ Anon., 2008. 7 Medical Battalion Group - a unique unit. The South African Soldier, 15(), p. 38–39.

- ↑ Engelbrecht, Leon (2008-11-26). "Fact file: Capabilities of the SA Military Health Service" (in en-ZA). https://www.defenceweb.co.za/joint/logistics/fact-file-capabilities-of-the-sa-military-health-service/.

- ↑ Le Roux, L., 2005. The post-apartheid South African military: Transforming with the nation. Evolutions and Revolutions: A Contemporary History of Militaries in Southern Africa. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, pp. pp.235-68..

- ↑ Wessels, André. "The South African National Defence Force, 1994–2009: A Historical Perspective" (PDF). humanities.ufs.ac.za/. University of the Free State. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ Charney, C., 1999. Civil Society, Political Violence, and Democratic Transitions: Business and the Peace Process in South Africa, 1990 to 1994. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 41(1), pp. 182-206.

- ↑ Vrey, F., 2012. Paradigm shifts, South African Defence Policy and the South African National Defence Force : from here to where?. Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies, 32(2), pp. 89-118.

- ↑ "SA Military Health Service MTEF Plan; with Minister | PMG" (in en). https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/30884/#:~:text=The%20Mobile%20Military%20Health%20formation,be%20located%20at%20military%20bases.

- ↑ "Military health support programme presentation to the portfolio committee on defence". https://static.pmg.org.za/docs/101117sahms-edit.pdf.

- ↑ Arreguín-Toft, I., . How the weak win wars: A theory of asymmetric conflict. [Online] Available at: http://web.stanford.edu/class/polisci211z/2.2/Arreguin-Toft%20IS%202001.pdf [Accessed 2 7 2023].

- ↑ Allen, M. A., Bell, S. R. & Clay, K. C., . Deadly Triangles: The Implications of Regional Competition on Interactions in Asymmetric Dyads. Foreign Policy Analysis, 14(2), p. 169–190.

- ↑ Forest, J. J. & Giroux, J., 2011. Terrorism and Political Violence in Africa: Contemporary Trends in a Shifting Terrain. Perspectives on terrorism, 5(), p. .

- ↑ Fine, J., . Contrasting Secular and Religious Terrorism., (), p. .

- ↑ Smith, David (2011-01-24). "South Africa flood death toll rises as government declares 33 disaster zones" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jan/24/south-africa-flood-death-toll.

- ↑ Mabogunje, A. L., . The Environmental Challenges In Sub Saharan Africa. [Online] Available at: http://web.mit.edu/africantech/www/articles/EnvChall.htm

- ↑ Coghlan, M., 2002. The Natal volunteers in the Anglo-Boer War, September 1899 to July 1902: reality and perception, Durban: UKZN Press.

- ↑ Anon., . First Anglo-Boer War 1880-1881. [Online] Available at: http://www.sahistory.org.za/south-africa-1806-1899/first-anglo-boer-war-1880-1881 [Accessed 2 7 2023].

- ↑ Anon., . Boer War – Imperial Yeomanry Battalions. [Online] Available at: http://www.roll-of-honour.com/Regiments/ImperialYeomanryCompaniesBoerBn.html [Accessed 2 7 2023].

- ↑ Mohlamme, J., . Botched Orders or Insubordination:The battle of Berea revisited. SA Military History Journal, 10(1), p. .

- ↑ Waag, I. V. d., 2012. MILITARY NURSING IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1914-1994. Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies, 25(2), p. .

- ↑ "South Africa's defence policy in need of a resupply – Africa Portal" (in en-US). https://africaportal.org/feature/south-africas-defence-policy-need-resupply/.

- ↑ "2021 Review of the Military Health Support Programme within the Department of Defence". https://www.gtac.gov.za/pepa/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Military-Health-Spending-Review-Report.pdf.

- ↑ ISSAfrica.org (2023-06-07). "Is South Africa's defence force up for new thinking?" (in en). https://issafrica.org/iss-today/is-south-africas-defence-force-up-for-new-thinking.

- ↑ Goniewicz, Mariusz (2013). Bogucki, Sandy. ed. "Effect of Military Conflicts on the Formation of Emergency Medical Services Systems Worldwide" (in en). Academic Emergency Medicine 20 (5): 507–513. doi:10.1111/acem.12129. PMID 23672366.

- ↑ Alden, Chris; Schoeman, Maxi (2015-02-01). "South Africa's symbolic hegemony in Africa" (in en). International Politics 52 (2): 239–254. doi:10.1057/ip.2014.47. ISSN 1740-3898. https://doi.org/10.1057/ip.2014.47.

- ↑ Park, M., 1916. German South-West African Campaign.. Journal of the Royal African Society, pp. 15(58), pp.113-132..

- ↑ Dunning, F., 1936. Personal reminiscences with a mobile veterinary section in the South-West African campaign, 1915.. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association, 7(1), pp. pp.7-10..

- ↑ Kleynhans, E., 2016. A critical analysis of the impact of water on the South African campaign in German South West Africa, 1914-1915.. Historia, 61(2), pp. pp.29-53..

- ↑ Headrick, R., 1978. African Soldiers in World War II. Armed Forces & Society, 4(3), pp. pp.501-526..

- ↑ Mohlamme, J., . Botched Orders or Insubordination:The battle of Berea revisited. SA Military History Journal, 10(1), p. .

- ↑ "The general strike of 1922". https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive-files3/sloct93.8.pdf.

- ↑ Popke, E., 2000. Violence and memory in the reconstruction of South Africa's Cato Manor.. Growth and Change, 3(12), pp. pp.235-254..

- ↑ Faulkner, D. & Loewald, C., 2008. Policy change and economic growth : a case study of South Africa. [Online] Available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/extpremnet/resources/489960-1338997241035/growth_commission_working_paper_41_policy_change_economic_growth_case_study_south_africa.pdf

- ↑ "State Civil Society Relations in South Africa: Some Lessons from Engagement – Africa Portal" (in en-US). https://africaportal.org/publication/state-civil-society-relations-in-south-africa-some-lessons-from-engagement/.

- ↑ Banjo, A. a. B. S., 2009. A descriptive analysis of the 2007 public sector strike in South Africa: forum section. South African Journal of Labour Relations, 33(2), pp. pp.120-131.

- ↑ to civil turmoil 2021: Socio-economic and environmental consequences. Cities, Volume 124, p. p.103612..

- ↑ Connell, M. O. O. S. U. a. O. S., 2013. Post traumatic stress disorder and resilience in veterans who served in the South African border war: original.. African Journal of Psychiatry, 16(6), pp. pp.430-436..

- ↑ Baines, G. a. V. P., 2008. Beyond the Border War: new perspectives on Southern Africa's late-Cold War conflicts.. 1 ed. Pretoria: Unisa Press.

- ↑ Marius, W., 2006. OPS Medic-operational medical orderlies during the Border War.. Journal for Contemporary History, 3(13), pp. pp.326-348..

- ↑ Scholtz, L., 2012. The lessons of the Border War. Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies, 40(3), pp. pp.318-353..

- ↑ Pherudi, M., 2003. Operation Boleas under microscope, 1998-1999.. Journal for Contemporary History, 28(1), pp. pp.123-137.

- ↑ "Operation Boleas under microscope, 1998-1999". https://journals.ufs.ac.za/index.php/jch/article/download/354/337.

- ↑ Gibson, Erika. "SANDF deploys Combat Team Alpha to fight Mozambique insurgents" (in en-US). https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/sandf-deploys-combat-team-alpha-to-fight-mozambique-insurgents-20220221.

- ↑ Heitman, H. R., . How deadly CAR battle unfolded. [Online] Available at: http://www.iol.co.za/sundayindependent/how-deadly-car-battle-unfolded-1.1493841#.VBkC3_mSwqY

- ↑ Van Rensburg, W. V. F. a. N. T., 2020.. From Boleas to Bangui: parliamentary oversight of South African defence deployments.. Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies, 48(1), pp. pp.1-21.

- ↑ Dickens, Peter (2017-04-12). "Cpl. Ngobese joins a proud legacy of bravery in 7 Medical Battalion Group" (in en). https://samilhistory.com/2017/04/12/cpl-ngobese-joins-a-proud-legacy-of-bravery-in-7-medical-battalion-group/.

Template:Africa Template:South Africa Template:Gauteng Province Template:Pretoria Template:South African National Defence Force

|