PaX

PaX is a patch for the Linux kernel that implements least privilege protections for memory pages. The least-privilege approach allows computer programs to be able to restrict the set of operations they are allowed to perform–in the case of PaX, the ability to execute data as code, which is generally not applicable outside of certain kinds of programs (such as just-in-time compilers) but is often used for exploitation. PaX was first released in 2000.

PaX flags data memory as non-executable and program memory as non-writable. This can help prevent some security exploits, such as those stemming from certain kinds of buffer overflows, by preventing the execution of unintended code. PaX also features address space randomization features to make return-to-libc (ret2libc) attacks statistically difficult to exploit. However, these features do not protect against attacks overwriting variables and pointers.

PaX is maintained by The PaX Team, whose principal coder is anonymous. The grsecurity project includes PaX, along with other Linux kernel patches unique to grsecurity. All newer versions of PaX starting with 2014 are only found as a part of the grsecurity patchset.

Significance

This section may contain excessive or inappropriate references to self-published sources. (August 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Various types of computer insecurities are caused by errors in programs that make it possible to alter their function, effectively allowing them to be "rewritten" while running. The first 44 security notices issued by Ubuntu can be categorized[1] to show that 41% of vulnerabilities stem from buffer overflows, 11% from integer overflows, and 16% from other bad handling of malformed data. These types of bugs often open the possibility to inject and execute foreign code, or execute existing code out of order, and make up 61% of the sample group, discarding overlap. (This is a crude analysis; a more comprehensive analysis of individual vulnerabilities would be likely to give very different numbers.) Many worms, viruses, and attempts to take over a machine rely on changing the contents of memory so that the malware code is executed; or on executing "data" contents by misdirection. If execution of such malware could be blocked, it could do little or even no damage even after being installed on a computer; many, such as the Sasser worm, could be prevented from being installed at all.

PaX was designed to do just that for a large number of possible attacks, and to do so in a very generally applicable way. It prevents execution of improper code by controlling access to memory (read, write, or execute access; or combinations thereof) and is designed to do so without interfering with execution of proper code. At the cost of a small amount of overhead, PaX reduces many security exploits to a denial of service (DoS) or a remote code-flow control; exploits which would normally give attackers root access, allow access to important information on a hard drive, or cause other damage that will instead cause the affected program or process to crash with little effect on the rest of the system.

A DoS attack (or its equivalent) is generally an annoyance, and may in some situations cause loss of time or resources (e.g. lost sales for a business whose website is affected); however, no data should be compromised when PaX intervenes, as no information will be improperly copied elsewhere. Nevertheless, the equivalent of a DoS attack is in some environments unacceptable; some businesses have level of service contracts or other conditions which make successful intruder entry a less costly problem than loss of or reduction in service. The PaX approach is thus not well suited to all circumstances; however, in many cases, it is an acceptable method of protecting confidential information by preventing successful security breaches.

Many, but not all, programming bugs cause memory corruption. Of those that do, and are triggerable by intent, some will make it possible to induce the program to do various things it was not meant to, such as producing a high-privilege shell. The focus of PaX is not on the finding and fixing of such bugs, but rather on prevention and containment of exploit techniques which may stem from such programmer error. A subset of these bugs will be reduced in severity; programs terminate, rather than improperly provide service.

PaX does not directly prevent buffer overflows; instead, it effectively prevents many of these and related programming bugs from being used to gain unauthorized entry into a computer system. Other systems such as Stack-Smashing Protector and StackGuard do attempt to directly detect buffer overflows, and kill the offending program when identified; this approach is called stack-smashing protection, and attempts to block such attacks before they can be made. PaX's more general approach, on the other hand, prevents damage after the attempt begins. Although both approaches can achieve some of the same goals, they are not entirely redundant. Therefore, employing both will, in principle, make an operating system more secure.

As of mid-2004, PaX has not been submitted to the mainline kernel tree because The PaX Team does not find it appropriate yet; although PaX is fully functional on many CPU architectures, including the widely used x86 architecture, it still remains partially or fully unimplemented on some architectures. Those that PaX is effective on include IA-32 (x86), AMD64, IA-64, Alpha, PA-RISC, and 32 and 64 bit MIPS, PowerPC, and SPARC architectures.

Limitations

PaX cannot block fundamental design flaws in either executable programs or in the kernel that allow an exploit to abuse supplied services, as these are in principle undetectable. For example, a script engine which allows file and network access may allow malicious scripts to steal confidential data through privileged users' accounts. PaX also cannot block some format string bug based attacks, which may allow arbitrary reading from and writing to data locations in memory using already existing code; the attacker does not need to know any internal addresses or inject any code into a program to execute these types of attacks.

The PaX documentation,[2] maintained on the PaX Web site, describes three classes of attacks which PaX attempts to protect against. The documentation discusses both attacks for which PaX will be effective in protecting a system and those for which it will not. All assume a full, position-independent executable base with full Executable Space Protections and full Address Space Layout Randomization. Briefly, then, blockable attacks are:

- Those which introduce and execute arbitrary code. These types of attacks frequently involve shellcode.

- Those which attempt to execute existing program code out of the original order intended by the computer programmer(s). This is commonly called a return-to-libc attack, or ret2libc for short.

- Those which attempt to execute existing program code in the intended order with arbitrary data. This issue existed in zlib versions before 1.1.4—a corrupt compressed stream could cause a double-free.

Because PaX is aimed at preventing damage from specific types attacks rather than finding and fixing the bugs that permit them, it cannot protect against all kinds of attacks; indeed, preventing all attacks is impossible.

The first class of attacks is still possible with 100% reliability in spite of using PaX if the attacker does not need advance knowledge of addresses in the attacked task.

The second and third classes of attacks are also possible with 100% reliability, if the attacker needs advance knowledge of address space layout and can derive this knowledge by reading the attacked task's address space. This is possible if the target has a bug which leaks information, e.g., if the attacker has access to /proc/(pid)/maps. There is an obscurity patch which NULLs out the values for the address ranges and inodes in every information source accessible from userland to close most of these holes; however, it is not currently included in PaX.

The second and third classes of attacks are possible with a small probability if the attacker needs advance knowledge of address space layout, but cannot derive this knowledge without resorting to guessing or to a brute force search. The ASLR documentation[3] describes how one can further quantify the "small probability" these attacks have of success.

The first class of attacks is possible if the attacker can have the attacked task create, write to, and mmap() a file. This in turn requires the second attack method to be possible, so an analysis of that applies here as well. Although not part of PaX, it is recommended—among other things—that production systems use an access control system that prevents this type of attack.

Responsible system administration is still required even on PaXified systems. PaX prevents or blocks attacks which exploit memory corruption bugs, such as those leading to shellcode and ret2libc attacks. Most attacks that PaX can prevent are related to buffer overflow bugs. This group includes the most common schemes used to exploit memory management problems. Still, PaX cannot prevent all of such attacks.

Features

PaX offers executable space protection, using (or emulating in operating system software) the functionality of an NX bit (i.e., built-in CPU and MMU support for memory contents execution privilege tagging). It also provides address space layout randomization to defeat ret2libc attacks and all other attacks relying on known structure of a program's virtual memory.

Executable space protections

The major feature of PaX is the executable space protection it offers. These protections take advantage of the NX bit on certain processors to prevent the execution of arbitrary code. This staves off attacks involving code injection or shellcode. On IA-32 CPUs where there is no NX bit, PaX can emulate the functionality of one in various ways.

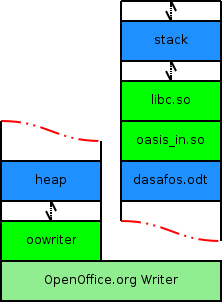

Many operating systems, Linux included, take advantage of existing NX functionality in hardware to apply proper restrictions to memory. Fig. 1 shows a simple set of memory segments in a program with one loaded library; green segments are data and blue are code. In normal cases, the address space on AMD64 and other such processors will by default look more like Fig. 1, with clearly defined data and code. Unfortunately, Linux by default does not prohibit an application from changing any of its memory protections; any program may create data-code confusion, marking areas of code as writable and areas of data as executable. PaX prevents such changes, as well as guaranteeing the most restrictive default set suitable for typical operation.

When the Executable Space Protections are enabled, including the mprotect() restrictions, PaX guarantees that no memory mappings will be marked in any way in which they may be executed as program code after it has been possible to alter them from their original state. The effect of this is that it becomes impossible to execute memory during and after it has been possible to write to it, until that memory is destroyed; and thus, that code cannot be injected into the application, malicious or otherwise, from an internal or external source.

The fact that programs cannot themselves execute data they originated as program code poses an impassable problem for applications that need to generate code at runtime as a basic function, such as just-in-time compilers for Java; however, most programs that have difficulty functioning properly under these restrictions can be debugged by the programmer and fixed so that they do not rely on this functionality. For those that simply need this functionality, or those that haven't yet been fixed, the program's executable file can be marked by the system administrator so that it does not have these restrictions applied to it.

The PaX team had to make some design decisions about how to handle the mmap() system call. This function is used to either map shared memory, or to load shared libraries. Because of this, it needs to supply writable or executable RAM, depending on the conditions it is used under.

The current implementation of PaX supplies writable anonymous memory mappings by default; file backed memory mappings are made writable only if the mmap() call specifies the write permission. The mmap() function will never return mappings that are both writable and executable, even if those permissions are explicitly requested in the call.

Enforced non-executable pages

By default, Linux does not supply the most secure usage of non-executable memory pages, via the NX bit. Furthermore, some architectures do not even explicitly supply a way of marking memory pages non-executable. PaX supplies a policy to take advantage of non-executable pages in the most secure way possible.

In addition, if the CPU does not provide an explicit NX bit, PaX can emulate (supply) an NX bit by one of several methods. This degrades performance of the system, but increases security greatly. Furthermore, the performance loss in some methods may be low enough to be ignored.

PAGEEXEC

PAGEEXEC uses or emulates an NX bit. On processors which do not support a hardware NX, each page is given an emulated NX bit. The method used to do this is based on the architecture of the CPU. If a hardware NX bit is available, PAGEEXEC will use it instead of emulating one, incurring no performance costs.

On IA-32 architectures, NX bit emulation is done by changing the permission level of non-executable pages. The Supervisor bit is overloaded to represent NX. This causes a protection fault when access occurs to the page and it is not yet cached in the translation lookaside buffer. In this case, the memory management unit alerts the operating system; on IA-32, the MMU typically has separate TLB caches for execution (ITLB) and read/write (DTLB), so this fault also allows Linux and PaX to determine whether the program was trying to execute the page as code. If an ITLB fault is caught, the process is terminated[clarify]; otherwise Linux forces a DTLB load to be allowed, and execution continues as normal.

PAGEEXEC has the advantage of not dividing the memory address space in half; tasks still each get a 3 GB virtual ramspace rather than a 1.5/1.5 split. However, for emulation, it is slower than SEGMEXEC and caused a severe performance detriment in some cases.

Since May 2004, the newer PAGEEXEC code for IA-32 in PaX tracks the highest executable page in virtual memory, and marks all higher pages as user pages. This allows data pages above this limit—such as the stack—to be handled as normal, with no performance loss. Everything below this area is still handled as before. This change is similar to the Exec Shield NX implementation, and the OpenBSD W^X implementation; except that PaX uses the Supervisor bit overloading method to handle NX pages in the code segment as well.

SEGMEXEC

SEGMEXEC emulates the functionality of an NX bit on IA-32 (x86) CPUs by splitting the address space in half and mirroring the code mappings across the address space. When there is an instruction fetch, the fetch is translated across the split. If the code is not mapped there, then the program is killed.

SEGMEXEC cuts the task's virtual memory space in half. Under normal circumstances, programs get a VM space 3GiB wide, which has physical memory mapped into it. Under SEGMEXEC, this becomes a 1.5/1.5 GiB split, with the top half used for the mirroring. Despite this, it does increase performance if emulation must be done on IA-32 (x86) architectures. The mapping in the upper and lower half of the memory space is to the same physical memory page, and so does not double RAM usage.

Restricted mprotect()

PaX is supposed to guarantee that no RAM is both writable and executable. One function, the mprotect() function, changes the permissions on a memory area. The Single UNIX Specification defines mprotect() with the following note in its description:

- If an implementation cannot support the combination of access types specified by prot, the call to mprotect() shall fail.

The PaX implementation does not allow a memory page to have permissions PROT_WRITE and PROT_EXEC both enabled when mprotect() restrictions are enabled for the task; any call to mprotect() to set both (PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC) at the same time will fail due to EACCESS (Permission Denied). This guarantees that pages will not become both writable and executable, and thus fertile ground for simple code injection attacks.

Similar failure occurs if mprotect(...|PROT_EXEC) occurs on a page that does not have the PROT_EXEC restriction already on. The failure here is justified; if a PROT_WRITE page has code injected into it, and then is made PROT_EXEC, a later retriggering of the exploit allowing code injection will allow the code to be executed. Without this restriction, a three-step exploit is possible: Inject code, ret2libc::ret2mprotect(), execute code.

With mprotect() restrictions enabled, a program can no longer violate the non-executable pages policy that PaX initially sets down on all memory allocations; thus, restricted mprotect() could be considered to be strict enforcement of the security policy, whereas the "Enforced non-executable pages" without these restrictions could be considered to be a looser form of enforcement.

Trampoline emulation

Trampolines are usually implemented by gcc as small pieces of code generated at runtime on the stack. Thus, they require executing memory on the stack, which triggers PaX to kill the program.

Because trampolines are runtime generated code, they trigger PaX and cause the program using them to be killed. PaX is capable of identifying the setup of trampolines and allowing their execution. This is, however, considered to produce a situation of weakened security.

Address space layout randomization

Address space layout randomization, or ASLR, is a technique of countering arbitrary execution of code, or ret2libc attacks. These attacks involve executing already existing code out of the order intended by the programmer.

ASLR as provided in PaX shuffles the stack base and heap base around in virtual memory when enabled. It also optionally randomizes the mmap() base and the executable base of programs. This substantially lowers the probability of a successful attack by requiring the attacking code to guess the locations of these areas.

Fig. 2 shows qualitative views of process' address spaces with address space layout randomization. The half-head arrows indicate a random gap between various areas of virtual memory. At any point when the kernel initializes the process, the length of these arrows can be considered to grow longer or shorter from this template independent of each other.

During the course of a program's life, the heap, also called the data segment or .bss, will grow up; the heap expands towards the highest memory address available. Conversely, the stack grows down, towards the lowest memory address, 0.

It is extremely uncommon for a program to require a large percent of the address space for either of these. When program libraries are dynamically loaded at the start of a program by the operating system, they are placed before the heap; however, there are cases where the program will load other libraries, such as those commonly referred to as plugins, during run. The operating system or program must choose an acceptable offset to place these libraries at.

PaX leaves a portion of the addresses, the MSBs, out of the randomization calculations. This helps assure that the stack and heap are placed so that they do not collide with each other, and that libraries are placed so that the stack and heap do not collide with them.

The effect of the randomization depends on the CPU. 32-bit CPUs will have 32 bits of virtual address space, allowing access to 4GiB of memory. Because Linux uses the top 1 GB for the kernel, this is shortened to 3GiB. SEGMEXEC supplies a split down the middle of this 3GiB address space, restricting randomization down to 1.5GiB. Pages are 4KiB in size, and randomizations are page aligned. The top four MSBs are discarded in the randomization, so that the heap exists at the beginning and the stack at the end of the program. This computes down to having the stack and heap exist at one of several million positions (23 and 24 bit randomization), and all libraries existing in any of approximately 65,000 positions.

On 64-bit CPUs, the virtual address space supplied by the MMU may be larger, allowing access to more memory. The randomization will be more entropic in such situations, further reducing the probability of a successful attack in the lack of an information leak.

Randomized stack base

PaX randomly offsets the base of the stack in increments of 16 bytes, combining random placement of the actual virtual memory segment with a sub-page stack gap. The total magnitude of the randomization depends on the size of virtual memory space; for example, the stack base is somewhere in a 256MiB range on 32-bit architectures, giving 16 million possible positions or 24 bits of entropy.

The randomization of the stack base has an effect on payload delivery during shellcode and return-to-libc attacks. Those kind of attacks modify the return pointer field to the address of the payload. Provided that the address of the stack is not leaked and thus unknown to the adversary, the probability of success is diminished significantly; the position of the stack is unpredictable, and missing the payload likely causes the program to crash.

In the case of shellcode, a series of instructions called a NOP slide or NOP sled can be prepended to the payload. This will add one more success case per 16 bytes of NOP slide. 16 bytes of NOP slide increase the success rate from 1/16M to 2/16M; 128 bytes of NOP slide increase this to 9/16M. The increase in success rate is directly proportional to the size of the NOP slide; doubling the length of any given NOP slide doubles the chances of a successful attack.

Return-to-libc attacks do not use code, but rather inject fixed width stack frames. Because of this, stack frames have to repeat exactly aligned to 16 bytes. Often a stack frame will be bigger than this, giving repeated stack frame payloads of the same length as a given NOP sled less of an impact on the success rate of attacks.

Randomized mmap() base

In POSIX systems, the mmap() system call allows for memory to be allocated at offsets specified by the process or selected by the kernel. This can be anonymous memory with nothing in it; or file backed memory mappings, which simulate a portion of a file or a copy of said portion to be in memory at that point. Program libraries are loaded in by using mmap() to map their code and data private—the files are copied to memory if they are changed, rather than rewritten on disk.

Any mmap() call may or may not specify an offset in virtual memory to allocate the mapping at. If an offset is not specified, it is up to the operating system to select one. Linux does this by calculating an offset in a predictable manner, starting from a predefined virtual address called the mmap() base. Because of this, every run of a process loads initial libraries such as the C standard library or libc in the same place.

When Randomized mmap() base is enabled, PaX randomly shifts the mmap() base, affecting the positioning of all libraries and other non-specific mmap() calls. This causes all dynamically linked code, i.e. shared objects, to be mapped at a different, randomly selected offset every time. Attackers requiring a function in a certain library must guess where that library is loaded in virtual memory space to call it. This makes return-to-libc attacks difficult; although shellcode injections can still look up the address of any function in the global offset table.

PaX does not change the load order of libraries. This means if an attacker knows the address of one library, he can derive the locations of all other libraries; however, it is notable that there are more serious problems if the attacker can derive the location of a library in the first place, and extra randomization will not likely help that. Further, typical attacks only require finding one library or function; other interesting elements such as the heap and stack are separately randomized and are not derivable from the mmap() base.

When ET_DYN executables—that is, executables compiled with position-independent code in the same way as shared libraries—are loaded, their base is also randomly chosen, as they are mmap()ed into RAM just like regular shared objects.

When combining a non-executable stack with mmap() base randomization, the difficulty in exploiting bugs protected against by PaX is greatly increased due to the forced use of return-to-libc attacks. On 32-bit systems, this amounts to 16 orders of magnitude; that is, the chances of success are recursively halved 16 times. Combined with stack randomization, the effect can be quite astounding; if every person in the world (assuming 6 billion total) attacks the system once, roughly 1 to 2 should succeed on a 32-bit system. 64-bit systems of course benefit from greater randomization.

Randomized ET_EXEC base

PaX is able to map non-position-independent code randomly into RAM; however, this poses a few problems. First, it incurs some extra performance overhead. Second, on rare occasions it causes false alarms, bringing PaX to kill the process for no reason. It is strongly recommended that executables be compiled ET_DYN, so that they are 100% position-independent code.

The randomization of the executable load base for ET_EXEC fixed position executables was affected by a security flaw in the VM mirroring code in PaX. For those that hadn't upgraded, the flaw could be worked around by disabling SEGMEXEC NX bit emulation and RANDEXEC randomization of the executable base.

Binary markings

PaX allows executable files in the Executable and Linkable Format to be marked with reduced restrictions via the chpax and paxctl tools. These markings exist in the ELF header, and thus are both filesystem-independent and part of the file object itself. This means that the markings are retained through packaging, copying, archiving, encrypting, and moving of the objects. The chpax tool is deprecated in favor of paxctl.

PaX allows individual markings for both PAGEEXEC and SEGMEXEC; randomizing the mmap(), stack, and heap base; randomizing the executable base for ET_EXEC binaries; restricting mprotect(); and emulating trampolines.

In the case of chpax, certain tools such as strip may lose the markings; using paxctl to set the PT_PAX_FLAGS is the only reliable method. The paxctl tool uses a new ELF program header specifically created for PaX flags. These markings can be explicitly on, off, or unset. When unset, the decision on which setting to use is made by the PaX code in the kernel, and is influenced by the system-wide PaX softmode setting.

History

This is an incomplete history of PaX to be updated as more information is located.

- October, 2000: PaX first released with basic PAGEEXEC method

- November, 2000: first incarnation of MPROTECT released

- June, 2001: ASLR (mmap randomization) implemented, not released

- July, 2001: ASLR released

- August, 2001: ASLR with additional stack and PIE randomization released

- July, 2002: VMA Mirroring and RANDEXEC released

- October, 2002: SEGMEXEC released

- October, 2002: ASLR with additional kernel stack randomization released

- February, 2003: EI_PAX ELF marking method introduced

- April, 2003: KERNEXEC (non-executable kernel pages) released

- July, 2003: ASLR with additional brk randomization released

- February, 2004: PT_PAX_FLAGS ELF marking method introduced

- May, 2004: PAGEEXEC augmented with code segment limit tracking for enhanced performance

- March 4, 2005: VMA Mirroring vulnerability announced, new versions of PaX and grsecurity released, all prior versions utilizing SEGMEXEC and RANDEXEC have a privilege escalation vulnerability

- April 1, 2005: Due to that vulnerability, the PaX project was scheduled to be taken over by a new developer, but, since no candidate showed up, the old developer has continued maintenance ever since.

See also

- Exec Shield

- Hardening (computing)

- Intrusion detection system

- Intrusion prevention system

- Security-Enhanced Linux

- RSBAC

References

Further reading

External links

- PaX homepage

- Future of PaX 2003

- Presentation on PaX 2003-10-14

- Trampolines for Nested Functions

- Exploit Mitigation Techniques 2004

- Ubuntu Linux USN Analysis

- PaX privilege elevation security bug March 9, 2005

- PaX privilege elevation proof-of-concept code 2005