Philosophy:Führerprinzip

The Führerprinzip (German: [ˈfyːʀɐpʀɪnˌtsiːp] (![]() listen); German for 'leader principle') prescribed the fundamental basis of political authority in the Government of Nazi Germany. This principle can be most succinctly understood to mean that "the Führer's word is above all written law" and that governmental policies, decisions, and offices ought to work toward the realisation of this end.[1] In actual political usage, it refers mainly to the practice of dictatorship within the ranks of a political party itself, and as such, it has become an earmark of political fascism. Nazi Germany aimed to implement the leader principle at all levels of society, with as many organisations and institutions as possible being run by an individual appointed leader rather than by an elected committee. This included schools,[2] sports associations,[3] factories,[4] and more. A common theme of Nazi propaganda was that of a single heroic leader overcoming the adversity of committees, bureaucrats, and parliaments.[5] German history, from Frederick the Great and Otto von Bismarck, and Nordic sagas were interpreted to emphasise the value of unquestioning obedience to a visionary leader.[6]

listen); German for 'leader principle') prescribed the fundamental basis of political authority in the Government of Nazi Germany. This principle can be most succinctly understood to mean that "the Führer's word is above all written law" and that governmental policies, decisions, and offices ought to work toward the realisation of this end.[1] In actual political usage, it refers mainly to the practice of dictatorship within the ranks of a political party itself, and as such, it has become an earmark of political fascism. Nazi Germany aimed to implement the leader principle at all levels of society, with as many organisations and institutions as possible being run by an individual appointed leader rather than by an elected committee. This included schools,[2] sports associations,[3] factories,[4] and more. A common theme of Nazi propaganda was that of a single heroic leader overcoming the adversity of committees, bureaucrats, and parliaments.[5] German history, from Frederick the Great and Otto von Bismarck, and Nordic sagas were interpreted to emphasise the value of unquestioning obedience to a visionary leader.[6]

Ideology

The Führerprinzip was not invented by the Nazis. Hermann von Keyserling, a Baltic German philosopher from Estonia, was the first to use the term.[7] One of Keyserling's central claims was that certain "gifted individuals" were "born to rule" on the basis of Social Darwinism.

The ideology of the Führerprinzip sees each organisation as a hierarchy of leaders, where every leader (Führer, in German) has absolute responsibility in his own area, demands absolute obedience from those below him, and answers only to his superiors.[8] This required obedience and loyalty even over concerns of right and wrong.[8] The supreme leader, Adolf Hitler, answered to the German nation only. Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben has argued [9] that Hitler saw himself as an incarnation of auctoritas, and as the living law or highest law itself, effectively combining in his person executive power, judicial power, and legislative power. After the Night of the Long Knives, Hitler declared: "in this hour, I was responsible for the fate of the German nation and was therefore the supreme judge of the German people!"[10]

The Führerprinzip paralleled the functionality of military organisations, which continue to use a similar authority structure today, although in democratic countries members are supposed to be restrained by codes of conduct. The Freikorps – German paramilitary organisations made up of men who had fought in World War I and been mustered out after Germany's defeat, but who found it impossible to return to civilian life – were run on the Führer principle. Many of the same men had, earlier in life, been part of various German youth groups in the period from 1904–1913.[11] These groups had also accepted the idea of blind obedience to a leader.[12] The justification for the civil use of the Führerprinzip was that unquestioning obedience to superiors supposedly produced order and prosperity in which those deemed 'worthy' would share.

In the case of the Nazis, the Führerprinzip became integral to the Nazi Party in July 1921, when Adolf Hitler forced a showdown with the original leaders of the party after he learned that they were attempting to merge it with the somewhat larger German Socialist Party. Learning of this, and knowing that any merger would dilute his influence over the group, Hitler quit the Nazis. Realising that the party would be completely ineffective without Hitler as their front man, the founder of the party, Anton Drexler, opened negotiations with Hitler, who delivered an ultimatum: he must be recognised as the sole leader (Führer) of the party, with dictatorial powers. The executive committee gave in to his demands, and Hitler rejoined the party a few days later to become its permanent ruler, with Drexler demoted to honorary chairman for life.[13]

In time, as the party expanded, it fragmented somewhat, with the northern faction led by the Strasser brothers, Otto and Gregor, and including Joseph Goebbels, holding more Third Positionist views than the southern faction controlled by Hitler in Munich. They differed in other ways as well, including on the party's acceptance of the Führer Principle. In another confrontation engineered by Hitler, a party conference was called on 14 February 1926 in Bamberg. At this conference, Hitler won over the leaders of the northern faction with his oratorical skills, and the question of whether the NSDAP would follow the Führerprinzip was put to rest for good.[14]

When Hitler finally came to absolute power, after being appointed Chancellor and assuming the powers of the President when Paul von Hindenburg died, he changed his title to Führer und Reichskanzler ("Leader and Reich Chancellor"), and the Führerprinzip became an integral part of German society. Appointed mayors replaced elected local governments. Schools lost elected parents' councils and faculty advisory boards, with all authority being put in the headmaster's hands.[15] The Nazis suppressed associations and unions with elected leaders, putting in their place mandatory associations with appointed leaders. The authorities allowed private corporations to keep their internal organisation, but with a simple renaming from hierarchy to Führerprinzip. Conflicting associations—e.g., sports associations responsible for the same sport—were coordinated into a single one under the leadership of a single Führer, who appointed the Führer of a regional association, who appointed the sports club Führer, often appointing the person whom the club had previously elected.[3] Shop stewards had their authority carefully circumscribed to prevent their infringing on that of the plant leader.[4] Eventually, virtually no activity or organisation in Germany could exist that was completely independent of party or state leadership.

Carl Schmitt, a Nazi legal theorist and member of the Prussian State Council, published political essays and treatises endorsing Nazi purges and crimes on the basis of the doctrine of "Führerprinzip".[16][17] Portraying the Führerprinzip as the foundation of Nazi Germany's "total state", Schmitt wrote in his book "Staat, Bewegung, Volk " (1933):

"The strength of the National Socialist State lies in the fact that it is from top to bottom and in every atom of its existence ruled and permeated with the concept of leadership [Führertum]. This principle, which made the movement strong, must be carried through systematically both in the administration of the State and in the various spheres of self-government, naturally taking into account the modifications required by the particular area in question. But it would not be permissible for any important area of public life to operate independently from the Führer concept."[17]

Hermann Göring told Nevile Henderson that: "When a decision has to be taken, none of us counts more than the stones on which we are standing. It is the Führer alone who decides".[18] In practice, the selection of unsuitable candidates often led to micromanagement and commonly to an inability to formulate coherent policy. Albert Speer noted that many Nazi officials dreaded making decisions in Hitler's absence. Rules tended to become oral rather than written; leaders with initiative who flouted regulations and carved out their own spheres of influence might receive praise and promotion rather than censure.

Nazi propaganda

Many Nazi propaganda films promoted the importance of the Führerprinzip. Flüchtlinge depicted Volga German refugees saved from communist persecution by a leader demanding unquestioning obedience.[19] Der Herrscher altered its source material to depict its hero, Clausen, as the unwavering leader of his munitions firm, who, faced with his children's machinations, disowns them and bestows the firm on the state, confident that a worker will arise capable of continuing his work and, as a true leader, needing no instruction.[20] Carl Peters shows the title character in firm, decisive action to hold and win African colonies, but brought down by a parliament that does not realize the necessity of Führerprinzip.[21]

In the schools, adolescent boys were presented with Nordic sagas as the illustration of Führerprinzip, which was developed with such heroes as Frederick the Great and Otto von Bismarck.[22]

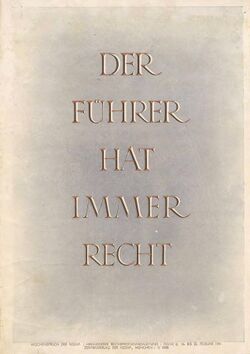

This was combined with the glorification of the one, central Führer, Adolf Hitler. During the Night of the Long Knives, it was claimed that his decisive action saved Germany,[23] though it meant (in Goebbels's description) suffering "tragic loneliness" from being a Siegfried forced to shed blood to preserve Germany.[24] In one speech Robert Ley explicitly proclaimed "The Führer is always right."[25] Booklets given out for the Winter Relief donations included The Führer Makes History,[26][27] a collection of Hitler photographs,[28] and The Führer’s Battle in the East[29] Films such as Der Marsch zum Führer and Triumph of the Will glorified him.

Carl Schmitt – drawn to the Nazi party by his admiration for a decisive leader[30] praised him in his pamphlet State, Volk and Movement because only the ruthless will of such a leader could save Germany and its people from the "asphalt culture" of modernity, to bring about unity and authenticity.[31]

Application

During the post-war Nuremberg Trials, Nazi war criminals – and, later, Adolf Eichmann during his trial in Israel – used the Führerprinzip concept to argue that they were not guilty of war crimes by claiming that they were only following orders. Eichmann may have declared his conscience was inconvenienced by war events in order to "do his job" as best he could.

In Eichmann in Jerusalem, Hannah Arendt concluded that, aside from a desire for improving his career, Eichmann showed no trace of antisemitism or psychological abnormalities whatsoever. She called him the embodiment of the "banality of evil", as he appeared at his trial to have an ordinary and common personality, displaying neither guilt nor hatred, denying any form of responsibility. Eichmann argued he was simply "doing his job" and maintained he had always tried to act in accordance with Immanuel Kant's categorical imperative.[32] Arendt suggested that these statements most strikingly discredit the idea that Nazi criminals were manifestly psychopathic and different from common people, that even the most ordinary of people can commit horrendous crimes if placed in the catalysing situation, and given the correct incentives. However, Arendt disagreed with this interpretation, as Eichmann justified himself with the Führerprinzip. Arendt argued that children obey, whereas adults adhere to an ideology.[citation needed]

See also

- Autocracy

- Charisma

- Cult of personality

- Functionalism versus intentionalism

- General Will

- Gleichschaltung

- Meine Ehre heißt Treue

- Milgram experiment

- Nuremberg Defense

- State of exception

- Supreme leader

- Superior orders

- Unrechtsstaat

References

Notes

- ↑ "Nazi Conspiracy & Aggression Volume I Chapter VII: Means Used by the Nazi Conspiractors in Gaining Control of the German State". A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust. usf.edu. https://fcit.usf.edu/HOLOCAUST/resource/document/DOCNAC3.htm.

- ↑ Nicholas (2006), p. 74

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Krüger, Arnd (1985). "'Heute gehört uns Deutschland und morgen ...?' Das Ringen um den Sinn der Gleichschaltung im Sport in der ersten Jahreshälfte 1933". in Buss, Wolfgang. Sportgeschichte: Traditionspflege und Wertewandel. Festschrift zum 75. Geburtstag von Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Henze. Duderstadt: Mecke. p. 175–196. ISBN 3-923453-03-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Grunberger, Richard (1971). The 12-Year Reich. New York: Henry Holt. p. 193. ISBN 0-03-076435-1.

- ↑ Leiser (1975), pp. 29–30, 104–105

- ↑ Nicholas (2006), p. 78

- ↑ Keyserling, Hermann (1921). Deutschlands wahre politische Mission. University of California Libraries. Darmstadt : O. Reichl. pp. see especially 28-32. http://archive.org/details/deutschlandswahr00keys.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Befehlsnotstand & the Führerprinzip". Shoah Education. http://www.shoaheducation.judahsglory.com/befehl.html.

- ↑ Agamben, Giorgio; Agamben, Giorgio (2008). State of exception (Nachdr. ed.). Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press. pp. eg. 2, 84 et. al. ISBN 978-0-226-00925-4.

- ↑ Sager, Alexander; Winkler, Heinrich August (2007). Germany: The Long Road West: 1933–1990. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926598-5.|page=37

- ↑ Savage, Jon (2007). Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture. New York: Viking. p. 101–112. ISBN 9780670038374.

- ↑ Mitcham (1996), p. 21

- ↑ Mitcham (1996), pp. 78–79

- ↑ Mitcham (1996), pp. 120–121

- ↑ Nicholas (2006), p. 74

- ↑ Griffin, Roger (2000). "11: Revolution from the Right: Fascism". in Parker, David. Revolutions and the Revolutionary Tradition: In the West 1560–1991. London: Routledge. pp. 193. ISBN 0-415-17294-2.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Griffin, Roger (1995). Fascism. Oxford University Press. pp. 138, 139. ISBN 978-0-19-289249-2.

- ↑ Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 19. https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.149663/2015.149663.Inside-Europe#page/n41/mode/2up.

- ↑ Leiser (1975), pp. 29–30

- ↑ Leiser (1975), p. 49

- ↑ Leiser (1975), pp. 104–105

- ↑ Nicholas (2006), p. 78

- ↑ Koonz (2003), p. 96

- ↑ Rhodes, Anthony (1976) Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, New York: Chelsea House. p. 16 ISBN 0877540292

- ↑ Ley, Robert (3 November 1937). "Fate – I Believe!". German Propaganda Archive. Calvin University. https://research.calvin.edu/german-propaganda-archive/ley2.htm.

- ↑ "Winterhilfswerk Booklet for 1933". German Propaganda Archive. Calvin University. https://research.calvin.edu/german-propaganda-archive/booklet2.htm.

- ↑ "Winterhilfswerk Booklet for 1938". German Propaganda Archive. Calvin University. https://research.calvin.edu/german-propaganda-archive/booklet3.htm.

- ↑ "Hitler in the Mountains". German Propaganda Archive. Calvin University. https://research.calvin.edu/german-propaganda-archive/booklet1.htm.

- ↑ "Hitler in the East". German Propaganda Archive. Calvin University. https://research.calvin.edu/german-propaganda-archive/booklet4.htm.

- ↑ Koonz (2003), p. 56

- ↑ Koonz (2003), p. 59

- ↑ Laustsen, Carsten Bagge; Ugilt, Rasmus (2007-01-01). "Eichmann's Kant". The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 21 (3): 166–180. doi:10.2307/jspecphil.21.3.0166. ISSN 0891-625X. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/jspecphil.21.3.0166.

Bibliography

- Koonz, Claudia (2003) The Nazi Conscience, Belknap. ISBN:0-674-01172-4

- Leiser, Erwin (1975) Nazi Cinema, New York: Macmillan. ISBN:0-02-570230-0

- Mitcham, Samuel W. (1996) Why Hitler? The Genesis of the Nazi Reich, Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-95485-4

- Nicholas, Lynn H. (2006) Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web, New York: Vintage. ISBN:0-679-77663-X

External links

|