Philosophy:Victorian morality

Victorian morality is a distillation of the moral views of the middle class in 19th-century Britain, the Victorian era.

Victorian values emerged in all social classes and reached all facets of Victorian living. The values of the period—which can be classed as religion, morality, Evangelicalism, industrial work ethic, and personal improvement—took root in Victorian morality. Contemporary plays and all literature—including old classics, like William Shakespeare's works—were cleansed of content considered to be inappropriate for children, or "bowdlerized".

Historians have generally come to regard the Victorian era as a time of many conflicts, such as the widespread cultivation of an outward appearance of dignity and restraint, together with serious debates about exactly how the new morality should be implemented. The international slave trade was abolished, and this ban was enforced by the Royal Navy. Slavery was ended in all the British colonies, child labour was ended in British factories, and a long debate ensued regarding whether prostitution should be totally abolished or tightly regulated. Male homosexuality was made illegal by the Labouchere Amendment.

Personal conduct

Victorian morality was a surprising new reality. The changes in moral standards and actual behaviour across the British were profound. Historian Harold Perkin wrote:

Between 1780 and 1850 the English ceased to be one of the most aggressive, brutal, rowdy, outspoken, riotous, cruel and bloodthirsty nations in the world and became one of the most inhibited, polite, orderly, tender-minded, prudish and hypocritical.[1]

Historians continue to debate the various causes of this dramatic change. Asa Briggs emphasizes the strong reaction against the French Revolution, and the need to focus British efforts on its defeat and not be diverged by pleasurable sins. Briggs also stresses the powerful role of the evangelical movement among the Nonconformists, as well as the evangelical faction inside the established Church of England. The religious and political reformers set up organizations that monitored behaviour, and pushed for government action.[2]

Among the higher social classes, there was a marked decline in gambling, horse races, and obscene theatres; there was much less heavy gambling or patronage of upscale houses of prostitution. The highly visible debauchery characteristic of aristocratic England in the early 19th century simply disappeared.[3]

Historians agree that the middle classes not only professed high personal moral standards, but actually followed them. There is a debate whether the working classes followed suit. Moralists in the late 19th century such as Henry Mayhew decried the slums for their supposed high levels of cohabitation without marriage and illegitimate births. However new research using computerized matching of data files shows that the rates of cohabitation were quite low—under 5%—for the working class and the poor. By contrast, in 21st-century Britain nearly half of all children are born outside marriage, and nine in ten newlyweds have been cohabitating.[4]

Slavery

Opposition to slavery was the main evangelical cause from the late 18th century, led by William Wilberforce (1759–1833). The cause organized very thoroughly, and developed propaganda campaigns that made readers cringe at the horrors of slavery. The same moral fervor and organizational skills carried over into most of the other reform movements.[5] Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837, only four years after the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire. The anti-slavery movement had campaigned for years to achieve the ban, succeeding with a partial abolition in 1807 and the full ban on slave trading, but not slave ownership, which only happened in 1833. It took so long because the anti-slavery morality was pitted against powerful economic interests which claimed their businesses would be destroyed if they were not permitted to exploit slave labour. Eventually, plantation owners in the Caribbean received £20 million in cash compensation, which reflected the average market price of slaves. William E. Gladstone, later a famous reformer, handled the large payments to his father for their hundreds of slaves. The Royal Navy patrolled the Atlantic Ocean, stopping any ships that it suspected of trading African slaves to the Americas and freeing any slaves found. The British had set up a Crown Colony in West Africa—Sierra Leone—and transported freed slaves there. Freed slaves from Nova Scotia founded and named the capital of Sierra Leone "Freetown".[6]

Abolishing cruelty

Cruelty to animals

William Wilberforce, Thomas Fowell Buxton and Richard Martin[7] introduced the first legislation to prevent cruelty to animals, the Cruel Treatment of Cattle Act 1822; it pertained only to cattle and it passed easily in 1822.[8]

In the Metropolitan Police Act 1839, "fighting or baiting Lions, Bears, Badgers, Cocks, Dogs, or other Animals" was made a criminal offence. The law laid numerous restrictions on how, when, and where animals could be used. It prohibited owners from letting mad dogs run loose and gave police the right to destroy any dog suspected of being rabid. It prohibited the use of dogs for drawing carts.[9] The law was extended to the rest of England and Wales in 1854. Dog-pulled carts were often used by very poor self-employed men as a cheap means to deliver milk, human foods, animal foods (the cat's-meat man), and for collecting refuse (the rag-and-bone man). The dogs were susceptible to rabies; cases of the disease among humans had been on the rise. They also bothered the horses, which were economically much more vital to the city. Evangelicals and utilitarians in the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals persuaded Parliament it was cruel and should be illegal; the Utilitarian element added government inspectors to provide enforcement. The owners had no more use for their dogs, and killed them.[10][11] Cart dogs were replaced by people with handcarts.[12]

Historian Harold Perkin writes:

Between 1780 and 1850 the English ceased to be one of the most aggressive, brutal, rowdy, outspoken, riotous, cruel and bloodthirsty nations in the world and became one of the most inhibited, polite, orderly, tender-minded, prudish and hypocritical. The transformation diminished cruelty to animals, criminals, lunatics, and children (in that order); suppressed many cruel sports and games, such as bull-baiting and cock-fighting, as well as innocent amusements, including many fairs and wakes; rid the penal code of about two hundred capital offences, abolished transportation [of criminals to Australia], and cleaned up the prisons; turned Sunday into a day of prayer for some and mortification for all.[13]

Child labour

Evangelical religious forces took the lead in identifying the evils of child labour, and legislating against them. Their anger at the contradiction between the conditions on the ground for children of the poor and the middle-class notion of childhood as a time of innocence led to the first campaigns for the imposition of legal protection for children. Reformers attacked child labour from the 1830s onward. The campaign that led to the Factory Acts was spearheaded by rich philanthropists of the era, especially Lord Shaftesbury, who introduced bills in Parliament to mitigate the exploitation of children at the workplace. In 1833, he introduced the Ten Hours Act 1833, which provided that children working in the cotton and woollen mills must be aged nine or above; no person under the age of eighteen was to work more than ten hours a day or eight hours on a Saturday; and no one under twenty-five was to work nights.[14] The Factories Act 1844 said children 9–13 years could work for at most 9 hours a day with a lunch break.[15] Additional legal interventions throughout the century increased the level of childhood protection, despite the resistance from the laissez-faire attitudes against government interference by factory owners. Parliament respected laissez-faire in the case of adult men, and there was minimal interference in the Victorian era.[16]

Unemployed street children suffered too, as novelist Charles Dickens revealed to a large middle class audience the horrors of London street life.[17]

Sexuality

Historians Peter Gay and Michael Mason both point out that modern society often confuses Victorian etiquette for a lack of knowledge. For example, people going for a bath in the sea or at the beach would use a bathing machine. Despite the use of the bathing machine, it was still possible to see people bathing nude. Contrary to popular conception, however, Victorian society recognised that both men and women enjoyed copulation.[18]

Regular sex was seen as important to male health. Married women were expected to agree to sex whenever their husbands wished for it, though it was seen as immoral for men to ask for sex in certain situations, such as when their wife was sick. Too much sex was seen as unhealthy, which led to a moral panic about masturbation, especially its perceived prevalence among middle class adolescent boys. Women were expected to be faithful to their husbands, or if unmarried, to refrain from sexual activity. There was more tolerance for men employing prostitutes or engaging in extramarital affairs. In the early Victorian period, a traditional idea that married women had an intense sex drive which needed to be controlled by their husband was still common. As the period progressed, this changed, with wives expected to control the sexual behaviour of men.[19]

Victorians also wrote explicit erotica, perhaps the most famous being the racy tell-all My Secret Life by the pseudonym Walter (allegedly Henry Spencer Ashbee), and the magazine The Pearl, which was published for several years and reprinted as a paperback book in the 1960s. Victorian erotica also survives in private letters archived in museums and even in a study of women's orgasms. Some current historians[who?] now believe that the myth of Victorian repression can be traced back to early 20th-century views, such as those of Lytton Strachey, a homosexual member of the Bloomsbury Group, who wrote Eminent Victorians.[citation needed]

Homosexuality

The enormous expansion of police forces, especially in London, produced a sharp rise in prosecutions for illegal sodomy at midcentury.[20] Male sexuality became a favorite subject of study especially by medical researchers whose case studies explored the progression and symptoms of institutionalized subjects. Henry Maudsley shaped late Victorian views about aberrant sexuality. George Savage and Charles Arthur Mercier wrote about homosexuals living in society. Daniel Hack Tuke's Dictionary of Psychological Medicine covered sexual perversion. All these works show awareness of continental insights, as well as moral disdain for the sexual practices described.[21]

Simeon Solomon and poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, as they contemplated their own sexual identities in the 1860s, fastened on the Greek lesbian poet Sappho. They made Victorian intellectuals aware of Sappho, and their writings helped to shape the modern image of lesbianism.[22]

The Labouchere Amendment to the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, for the first time, made all male homosexual acts illegal. It provided for two years' imprisonment for males convicted of committing, or being a party to public or private acts of homosexuality. Lesbian acts—still scarcely known—were ignored.[23] When Oscar Wilde was convicted of violating the statute, and imprisoned for such violations, in 1895, he became the iconic victim of English puritanical repression.[24]

Prostitution

During Victorian England, prostitution was seen as a "great social evil" by clergymen and major news organizations, but many feminists viewed prostitution as a means of economic independence for women. Estimates of the number of prostitutes in London in the 1850s vary widely, but in his landmark study, Prostitution, William Acton reported an estimation of 8,600 prostitutes in London alone in 1857.[25] The differing views on prostitution have made it difficult to understand its history.[citation needed]

Judith Walkowitz, a professor emerita at the department of history of the Johns Hopkins University, has multiple works focusing on the feminist point of view on the topic of prostitution. Many sources blame economic disparities as leading factors in the rise of prostitution, and Walkowitz writes that the demographic within prostitution varied greatly. However, women who struggled financially were much more likely to be prostitutes than those with a secure source of income. Orphaned or half-orphaned women were more likely to turn to prostitution as a means of income.[26] While overcrowding in urban cities and the amount of job opportunities for females were limited, Walkowitz argues that there were other variables that lead women to prostitution. Walkowitz acknowledges that prostitution allowed for women to feel a sense of independence and self-respect.[26] Although many assume that pimps controlled and exploited these prostitutes, some women managed their own clientele and pricing. It is evident that women were exploited by this system, yet Walkowitz says that prostitution was often their opportunity to gain social and economic independence.[26] Prostitution at this time was regarded by women in the profession to be a short-term position, and once they earned enough money, there were hopes that they would move on to a different profession.[27]

The arguments for and against prostitution varied greatly from it being perceived as a mortal sin or desperate decision to an independent choice. While there were plenty of people publicly denouncing prostitution in England, there were also others who took opposition to them. One event that sparked a lot of controversy was the implementation of the Contagious Diseases Acts. This was a series of three acts in 1864, 1866 and 1869 that allowed police officers to stop women whom they believed to be prostitutes and force them to be examined.[26] If the suspected woman was found with a venereal disease, they placed the woman into a lock hospital. Arguments made against the Acts claimed that the regulations were unconstitutional and that they only targeted women.[28] In 1869, a National Association in opposition of the acts was created. Because women were excluded from the first National Association, the Ladies National Association was formed. The leader of that organization was Josephine Butler.[26] Butler was an outspoken feminist during this time who fought for many social reforms. Her book Personal Reminiscences of a Great Crusade describes her oppositions to the Contagious Diseases Acts.[29] Along with the publication of her book, she also went on tours condemning the acts throughout the 1870s.[30] Other supporters of reforming the acts included Quakers, Methodists and many doctors.[28] Eventually the acts were fully repealed in 1886.[28]

Prostitutes were often presented as victims in sentimental literature such as Thomas Hood's poem The Bridge of Sighs, Elizabeth Gaskell's novel Mary Barton, and Dickens' novel Oliver Twist. The emphasis on the purity of women found in such works as Coventry Patmore's The Angel in the House led to the portrayal of the prostitute and fallen woman as soiled, corrupted, and in need of cleansing.[31]

This emphasis on female purity was allied to the stress on the homemaking role of women, who helped to create a space free from the pollution and corruption of the city. In this respect, the prostitute came to have symbolic significance as the embodiment of the violation of that divide. The double standard remained in force. The Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 allowed for a man to divorce his wife for adultery, but a woman could only divorce for adultery combined with other offences such as incest, cruelty, bigamy, desertion, etc., or based on cruelty alone.[32]

The anonymity of the city led to a large increase in prostitution and unsanctioned sexual relationships. Dickens and other writers associated prostitution with the mechanisation and industrialisation of modern life, portraying prostitutes as human commodities consumed and thrown away like refuse when they were used up. Moral reform movements attempted to close down brothels, something that has sometimes been argued to have been a factor in the concentration of street-prostitution.[33]

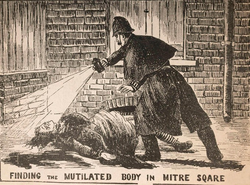

The extent of prostitution in London in the 1880s gained national and global prominence through the highly publicised murders attributed to Whitechapel-based serial killer Jack the Ripper, whose victims were exclusively prostitutes living destitute in the East End.[34] Given that many prostitutes were living in poverty as late as the 1880s and 1890s, offering sex services was a source of desperate necessity to fund their meals and temporary lodging accommodation from the cold, and as a result prostitutes represented easy prey for criminals as they could do little to personally protect themselves from harm.

Crime and police

After 1815, there was widespread fear of growing crimes, burglaries, mob action, and threats of large-scale disorder. Crime had been handled on an ad-hoc basis by poorly organized local parish constables and private watchmen, supported by very stiff penalties, including hundreds of causes for execution or deportation to Australia. London, with 1.5 million people—more than the next 15 cities combined—over the decades had worked out informal arrangements to develop a uniform policing system in its many boroughs. The Metropolitan Police Act 1829 (10 Geo. 4. c. 44), championed by Home Secretary Robert Peel, was not so much a startling innovation, as a systemization with expanded funding of established informal practices.[35] It created the Metropolitan Police Service, headquartered at Scotland Yard.[36] London now had the world's first modern police force. The 3,000 policemen were called "bobbies" (after Peel's first name). They were well-organized, centrally directed, and wore standard blue uniforms. Legally they had the historic status of constable, with authority to make arrests of suspicious persons and book offenders before a magistrate court. They were assigned in teams to specified beats, especially at night. Gas lighting was installed on major streets, making their task of surveillance much easier. Crime rates went down. An 1835 law required all incorporated boroughs in England and Wales to establish police forces. Scotland, with its separate legal system, was soon added. By 1857 every jurisdiction in Great Britain had an organized police force, for which the Treasury paid a subsidy. The police had steady pay, were selected by merit rather than by political influence, and were rarely used for partisan purposes. The pay scale was not high (one guinea a week in 1833), but the prestige was especially high for Irish Catholics, who were disproportionately represented in every city where they had a large presence.[37][38]

By the Victorian era, penal transportation to Australia was falling out of use since it did not reduce crime rates.[39] The British penal system underwent a transition from harsh punishment to reform, education, and training for post-prison livelihoods. The reforms were controversial and contested. In 1877–1914 era a series of major legislative reforms enabled significant improvement in the penal system. In 1877, the previously localized prisons were nationalized in the Home Office under a Prison Commission. The Prison Act 1898 (61 & 62 Vict. c. 41) enabled the Home Secretary to impose multiple reforms on his own initiative, without going through the politicized process of Parliament. The Probation of Offenders Act 1907 (7 Edw. 7. c. 17) introduced a new probation system that drastically cut down the prison population, while providing a mechanism for transition back to normal life. The Criminal Justice Administration Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5. c. 58) required courts to allow a reasonable time before imprisonment was ordered for people who did not pay their fines. Previously tens of thousands of prisoners had been sentenced solely for that reason. The Borstal system after 1908 was organized to reclaim young offenders, and the Children Act 1908 (8 Edw. 7. c. 67) prohibited imprisonment under age 14, and strictly limited that of ages 14 to 16. The principal reformer was Sir Evelyn Ruggles-Brise, the chair of the Prison Commission.[40][41]

Causation

Intellectual historians searching for causes of the new morality often point to the ideas by Hannah More, William Wilberforce, and the Clapham Sect. Perkin argues this exaggerates the influence of a small group of individuals, who were "as much an effect of the revolution as a cause." It also has a timing problem, for many predecessors had failed. The intellectual approach tends to minimize the importance of Nonconformists and Evangelicals—the Methodists, for example, played a powerful role among the upper tier of the working class. Finally, it misses a key ingredient: instead of trying to improve an old society, the reformers were trying to lead Britain into a new society of the future.[42]

Victorian era movements for justice, freedom, and other strong moral values made greed, and exploitation into public evils. The writings of Charles Dickens, in particular, observed and recorded these conditions.[43] Peter Shapely examined 100 charity leaders in Victorian Manchester. They brought significant cultural capital, such as wealth, education and social standing. Besides the actual reforms for the city they achieved for themselves a form of symbolic capital, a legitimate form of social domination and civic leadership. The utility of charity as a means of boosting one's social leadership was socially determined and would take a person only so far.[44]

The Marxist intellectual Walter Benjamin connected Victorian morality to the rise of the bourgeoisie. Benjamin alleged that the shopping culture of the petite bourgeoisie established the sitting room as the centre of personal and family life; as such, the English bourgeois culture is a sitting-room culture of prestige through conspicuous consumption. This acquisition of prestige is then reinforced by the repression of emotion and of sexual desire, and by the construction of a regulated social-space where propriety is the key personality trait desired in men and women.[45]

See also

- Religion in Victorian England

- Victorian Era

- The New Life (2022 historical fiction) by Tom Crewe

References

- ↑ Harold Perkin, The Origins of Modern English Society (1969) p. 280.

- ↑ Asa Briggs, The Age of Improvement: 1783–1867 (1959), pp. 66–74, 286–87, 436

- ↑ Ian C. Bradley, The Call to Seriousness: The Evangelical Impact on the Victorians (1976) pp. 106–109

- ↑ Rebecca Probert, "Living in Sin", BBC History Magazine (September 2012); G. Frost, Living in Sin: Cohabiting as Husband and Wife in Nineteenth-Century England (Manchester U.P. 2008)

- ↑ Seymour Drescher, Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery (2009) pp 205–44.

- ↑ Howard Temperley, British antislavery, 1833–1870 (1972).

- ↑ Wise, Steven M.. "Animal rights". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. https://www.britannica.com/topic/animal-rights#ref287259. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ↑ James C. Turner, Reckoning with the Beast: Animals, Pain, and Humanity in the Victorian Mind (2000) p 39.

- ↑ "London Police Act 1839, Great Britain Parliament. Section XXXI, XXXIV, XXXV, XLII". http://www.animalrightshistory.org/animal-rights-law/victorian-legislation/1839-uk-act-london-police.htm.

- ↑ M. B. McMullan, "The Day the Dogs Died in London" The London Journal: A Review of Metropolitan Society Past and Present (1998) 23#1 pp 32–40 https://doi.org/10.1179/ldn.1998.23.1.32

- ↑ Rothfels, Nigel (2002), Representing Animals, Indiana University Press, p. 12, ISBN 978-0-253-34154-9. Chapter: 'A Left-handed Blow: Writing the History of Animals' by Erica Fudge

- ↑ "igg.org.uk". http://www.igg.org.uk/gansg/00-app1/rthdbike.htm.

- ↑ Harold Perkin, The Origins of Modern English Society (1969) p 280.

- ↑ Georgina Battiscombe, Shaftesbury: A Biography of the Seventh Earl 1801–1885 (1988) pp. 88–91.

- ↑ Kelly, David (2014). Business Law. Routledge. p. 548. ISBN 9781317935124. https://books.google.com/books?id=wMhwAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA548.

- ↑ C. J. Litzenberger; Eileen Groth Lyon (2006). The Human Tradition in Modern Britain. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 142–43. ISBN 978-0-7425-3735-4.

- ↑ Amberyl Malkovich, Charles Dickens and the Victorian Child: Romanticizing and Socializing the Imperfect Child (2011)

- ↑ Draznin, Yaffa Claire (2001). Victorian London's Middle-Class Housewife: What She Did All Day (#179). Contributions in Women's Studies. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-313-31399-8.

- ↑ Goodman, Ruth (27 June 2013). "Chapter 15: Behind the bedroom door". How to be a Victorian. Penguin.

- ↑ Sean Brady, Masculinity and Male Homosexuality in Britain, 1861–1913 (2005).

- ↑ Crozier, Ivan (2008). "Nineteenth-century British psychiatric writing about homosexuality before Havelock Ellis: The missing story". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 63 (1): 65–102. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrm046. PMID 18184695.

- ↑ Prettejohn, Elizabeth (2008). "Solomon, Swinburne, Sappho". Victorian Review 34 (2): 103–128. doi:10.1353/vcr.2008.0034.

- ↑ Smith, F. Barry (1976). "Labouchere's amendment to the Criminal Law Amendment bill". Australian Historical Studies 17 (67): 165–173. doi:10.1080/10314617608595545.

- ↑ Adut, Ari (2005). "A theory of scandal: Victorians, homosexuality, and the fall of Oscar Wilde". American Journal of Sociology 111 (1): 213–248. doi:10.1086/428816. PMID 16240549. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7525127.

- ↑ Acton, William (1857). Prostitution Considered in its Moral, Social, and Sanitary Aspects (Reprint of the Second Edition with new biographical note ed.). London: Frank Cass (published 1972). ISBN 0-7146-2414-4.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Walkowitz, Judith (1980). Prostitution and Victorian Society. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Flanders, Judith (2014). "Prostitution". https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/report-on-prostitution.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Hamilton, Margaret (1978). "Opposition to the Contagious Diseases Acts 1864–1886". Albion (The North American Conference on British Studies) 10 (1): 14–27. doi:10.2307/4048453.

- ↑ Butler, Josephine (1976). Personal Reminiscences of a Great Crusade (Hyperion Reprint ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Hyperion Reprint Press. ISBN 0-88355-257-4.

- ↑ Nield, Keith (1973). "Introduction". Prostitution in the Victorian Age – Debates on the Issue From 19th Century Critical Journals. England: Gregg International Publishers Limited. ISBN 0576532517.

- ↑ George Watt, The fallen woman in the nineteenth-century English novel (1984)

- ↑ Nelson, Horace (1889). Selected cases, statutes and orders. London: Stevens and Sons Limited. p. 114. ISBN 9785877307049. https://archive.org/details/selectedcasesst00horagoog.

- ↑ Judith R. Walkowitz, "Male vice and feminist virtue: feminism and the politics of prostitution in nineteenth-century Britain." History Workshop (1982) 13:79–93. in JSTOR

- ↑ "Jack the Ripper | English Murderer". Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jack-the-Ripper.

- ↑ Gash, Norman (1961). Mr. Secretary Peel: The Life of Sir Robert Peel to 1830. Harvard University Press. pp. 487–98. ISBN 978-7-230-01232-4.

- ↑ Lyman, J. L. (1964). "The Metropolitan Police Act of 1829: An Analysis of Certain Events Influencing the Passage and Character of the Metropolitan Police Act in England". Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science 55 (1): 141–154. doi:10.2307/1140471. https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol55/iss1/18/.

- ↑ Clive Emsley, "Police" in James Eli Adams, ed., Encyclopedia of the Victorian Era (2004) 3:221–24.

- ↑ Clive Emsley, Crime and Society in England, 1750–1900 (5th ed. 2018) pp 216-61.

- ↑ Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, "Transportation from Britain and Ireland 1615–1870", History Compass 8#11 (2010): 1221–42.

- ↑ R. C. K. Ensor. England 1870–1914 (1937) pp 520–21.

- ↑ J. W. Fox, "The Modern English Prison" (1934).

- ↑ Perkin, The Origins of Modern English Society, pp 280–81.

- ↑ Daniel Bivona, "Poverty, pity, and community: Urban poverty and the threat to social bonds in the victorian age." Nineteenth-Century Studies 21 (2007): 67–83.

- ↑ Shapely, Peter (1998). "Charity, Status and Leadership: Charitable Image and the Manchester Man". Journal of Social History 32 (1): 157–177. doi:10.1353/jsh/32.1.157.

- ↑ Walter Benjamin, The Halles Project.

Further reading

- Adams, James Eli, ed. Encyclopedia of the Victorian Era (4 vol. 2004). articles by scholars

- Bartley, Paula. Prostitution: Prevention and reform in England, 1860–1914 (Routledge, 2012)

- Boddice, Rob. The Science of Sympathy: Morality, Evolution, and Victorian Civilization (2016)

- Bull, Sarah (2025). Selling Sexual Knowledge: Medical Publishing and Obscenity in Victorian Britain. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781009578103. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009578103.

- Churchill, David. Crime control and everyday life in the Victorian city: the police and the public (2017).

- Churchill, David C. (2014). "Rethinking the state monopolisation thesis: the historiography of policing and criminal justice in nineteenth-century England". Crime, Histoire & Sociétés/Crime, History & Societies 18 (1): 131–152. doi:10.4000/chs.1471. https://journals.openedition.org/chs/1471.

- Emsley, Clive.Crime and Society in England, 1750–1900 (5th ed. 2018)

- Fraser, Derek. The evolution of the British welfare state: a history of social policy since the Industrial Revolution (Springer, 1973).

- Gay, Peter. The Bourgeois Experience: Victoria to Freud

- Harrison, Brian (1955). "Philanthropy and the Victorians". Victorian Studies 9 (4): 353–374.

- Merriman, J (2004). A History of Modern Europe; From the French Revolution to the Present New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Perkin, Harold James (1969). The Origins of Modern English Society: 1780-1880. Routledge. ISBN 0-7100-4567-0. https://archive.org/details/originsofmoderne00haro/page/n6.

- Searle, G. R. Morality and the Market in Victorian Britain (1998)

- Woodward, E. L. The Age of Reform, 1815–1870 (1938); 692 pages; wide-ranging scholarly survey

Template:Victorian eraTemplate:Queen Victoria

|