Physics:Space-time adaptive processing

Space-time adaptive processing (STAP) is a signal processing technique most commonly used in radar systems. It involves adaptive array processing algorithms to aid in target detection. Radar signal processing benefits from STAP in areas where interference is a problem (i.e. ground clutter, jamming, etc.). Through careful application of STAP, it is possible to achieve order-of-magnitude sensitivity improvements in target detection.

STAP involves a two-dimensional filtering technique using a phased-array antenna with multiple spatial channels. Coupling multiple spatial channels with pulse-Doppler waveforms lends to the name "space-time." Applying the statistics of the interference environment, an adaptive STAP weight vector is formed. This weight vector is applied to the coherent samples received by the radar.

History

The theory of STAP was first published by Lawrence E. Brennan and Irving S. Reed in the early 1970s. At the time of publication, both Brennan and Reed were at Technology Service Corporation (TSC). While it was formally introduced in 1973,[1] it has theoretical roots dating back to 1959.[2]

Motivation and applications

For ground-based radar, cluttered returns tend to be at DC, making them easily discriminated by Moving Target Indication (MTI).[3] Thus, a notch filter at the zero-Doppler bin can be used.[2] Airborne platforms with ownship motion experience relative ground clutter motion dependent on the angle, resulting in angle-Doppler coupling at the input.[2] In this case, 1D filtering is not sufficient, since clutter can overlap the desired target's Doppler from multiple directions.[2] The resulting interference is typically called a "clutter ridge," since it forms a line in the angle-Doppler domain.[2] Narrowband jamming signals are also a source of interference, and exhibit significant spatial correlation.[4] Thus receiver noise and interference must be considered, and detection processors must attempt to maximize the signal-to-interference and noise ratio (SINR).

While primarily developed for radar, STAP techniques have applications for communications systems.[5]

Basic theory

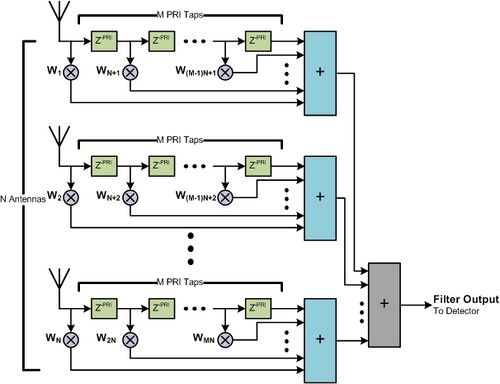

STAP is essentially filtering in the space-time domain.[2] This means that we are filtering over multiple dimensions, and multi-dimensional signal processing techniques must be employed.[6] The goal is to find the optimal space-time weights in -dimensional space, where is the number of antenna elements (our spatial degrees of freedom) and is the number of pulse-repetition interval (PRI) taps (our time degrees of freedom), to maximize the signal-to-interference and noise ratio (SINR).[2] Thus, the goal is to suppress noise, clutter, jammers, etc., while keeping the desired radar return. It can be thought of as a 2-D finite-impulse response (FIR) filter, with a standard 1-D FIR filter for each channel (steered spatial channels from an electronically steered array or individual elements), and the taps of these 1-D FIR filters corresponding to multiple returns (spaced at PRI time).[1] Having degrees of freedom in both the spatial domain and time domain is crucial, as clutter can be correlated in time and space, while jammers tend to be correlated spatially (along a specific bearing).[1]

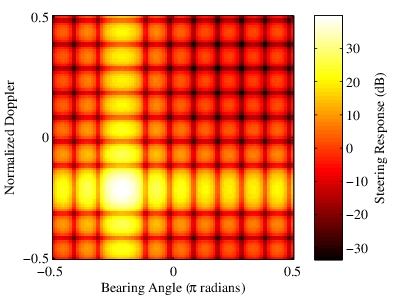

A simple, trivial example of STAP is shown in the first figure, for . This is an idealized example of a steering pattern, where the response of the array has been steered to the ideal target response, .[2] Unfortunately, in practice, this is oversimplified, as the interference to be overcome by steering the nulls shown is not deterministic, but statistical in nature.[2] This is what requires STAP to be an adaptive technique. Note that even in this idealized example, in general, we must steer over the 2-D angle-Doppler plane at discrete points to detect potential targets (moving the location of the 2-D sinc main lobe shown in the figure), and do so for each of the range bins in our system.

The basic functional diagram is shown to the right. For each antenna, a down conversion and analog-to-digital conversion step is typically completed. Then, a 1-D FIR filter with PRI length delay elements is used for each steered antenna channel. The lexicographically ordered weights to are the degrees of freedom to be solved in the STAP problem. That is, STAP aims to find the optimal weights for the antenna array. It can be shown, that for a given interference covariance matrix, , the optimal weights maximizing the SINR are calculated as

where is a scalar that does not affect the SINR.[2] The optimal detector input is given by:

where is a space-time snap-shot of the input data. The main difficulty of STAP is solving for and inverting the typically unknown interference covariance matrix, .[1] Other difficulties arise when the interference covariance matrix is ill-conditioned, making the inversion numerically unstable.[5] In general, this adaptive filtering must be performed for each of the unambiguous range bins in the system, for each target of interest (angle-Doppler coordinates), making for a massive computational burden.[4] Steering losses can occur when true target returns do not fall exactly on one of the points in our 2-D angle-Doppler plane that we've sampled with our steering vector .[1]

Approaches

The various approaches can be broken down by processing taxonomy,[7] or by simplifying the data space / data sources.[2]

Direct methods

The optimum solution is using all degrees of freedom by processing the adaptive filter on the antenna elements. For adaptive direct methods, Sample Matrix Inversion (SMI) uses the estimated (sample) interference covariance matrix in place of the actual interference covariance matrix.[8] This is because the actual interference covariance matrix is not known in practice.[1] If it is known by some means, then it need not be estimated, and the optimal weights are fixed. This is sometimes called the data-independent variation. The data-dependent variation estimates the interference covariance matrix from the data. In MIMO communications systems, this can be done via a training sequence.[5] The clairvoyant detector is given when the covariance matrix is known perfectly and defined as:

where is the space-time snapshot statistic for the range cell under the interference only hypothesis, .[1] For SMI, the interference covariance matrix for the range cell consisting of the statistics from interfering noise, clutter, and jammers is estimated as follows:[4]

where is the training data obtained from the input processor for the range cell. Therefore, space-time snapshots surrounding the desired range cell are averaged. Note that the desired range cell space-time snapshot is typically excluded (as well as a number of additional cells, or "guard cells") to prevent whitening of the statistics.[1]

The main problem with direct methods is the great computational complexity associated with the estimation and inversion of matrices formed from many degrees of freedom (large number of elements and or pulses).[1] In addition, for methods where must be estimated using data samples, the number of samples required to achieve a particular error is heavily dependent on the dimensionality of the interference covariance matrix.[4] As a result, for high dimensional systems, this may require an unachievable number of unambiguous range cells.[1] Further, these adjacent data cells must contain stationary statistics as a function of range which is rarely a good assumption for the large number of cells required ( for 3 dB SINR degradation from optimal, clairvoyant STAP).[2][1]

Reduced rank methods

Reduced rank methods aim to overcome the computational burdens of the direct method by reducing the dimensionality of the data or the rank of the interference covariance matrix.[2] This can be accomplished by forming beams and performing STAP on the beamspace.[7] Both pre and post Doppler methods can be used in the beamspace. Post Doppler methods may also be used on the full antenna element input as well to reduce the data in this dimension only. A popular example is displaced phase center antenna (DPCA), which is a form of data-independent STAP in the beamspace, pre-Doppler.[7] The goal is to perform beamforming such that the beam appears stationary as the airborne radar is in motion over discrete time periods so the clutter appears without Doppler.[2] However, phase errors can cause significant degradation since the algorithm is not adaptive to the returned data.[2] Many other methods may be used to reduce the rank of the interference covariance matrix, and so all methods in the reduced rank category can be thought of as simplifying the covariance matrix to be inverted:

Post-Doppler methods decompose the STAP problem from an adaptive filtering problem to individual adaptive filters of length (an adaptive filter problem).[2] By performing fixed Doppler processing, the adaptive filters become spatial only.[2] Since the target response is already steered to a specified angle-Doppler location, the dimensionality can be reduced by pre-processing multiple Doppler bins and angles surrounding this point.[4] In addition to reducing the dimensionality of the adaptive processor, this in turn reduces the number of required training data frames when estimating the interference covariance matrix since this quantity is dimension dependent.[2]

Since these methods reduce the data dimensionality, they are inherently sub-optimal.[1] There are a number of techniques to compare the performance of reduced-rank methods and estimated direct methods to clairvoyant STAP (direct with perfect knowledge of interference covariance matrix and target steering vector), mostly based around SINR loss.[1] One such example is

where we've taken the ratio of the SINR evaluated with the sub-optimal weights and the SINR evaluated with the optimal weights .[1] Note in general this quantity is statistical and the expectation must be taken to find the average SINR loss. The clairvoyant SINR loss may also be calculated by taking the ratio of the optimal SINR to the system SNR, indicating the loss due to interference.[1]

Model based methods

There are also model based methods that attempt to force or exploit the structure of the covariance interference matrix. The more generally applicable of these methods is the covariance taper matrix structure.[2] The goal is to compactly model the interference, at which point it can then be processed using principal component techniques or diagonal-loading SMI (where a small magnitude, random diagonal matrix is added to attempt to stabilize the matrix prior to inverting).[2] This modeling has an added benefit of decorrelating interference subspace leakage (ISL), and is resistant to internal clutter motion (ICM).[2] The principal component method firsts applies principal component analysis to estimate the dominant eigenvalues and eigenvectors, and then applies a covariance taper and adds an estimated noise floor:

where is the eigenvalue estimated using PCA, is the associated eigenvector estimated using PCA, implies element-by-element multiplication of matrices and , is the estimated covariance matrix taper, and is the estimated noise floor.[2] The estimation of the covariance taper can be complicated, depending on the complexity of the underlying model attempting to emulate the interference environment. The reader is encouraged to see [2] for more information on this particular subject. Once this taper is sufficiently modeled, it may also be applied to the more simple SMI adaptation of CMT as follows:

where is the typical SMI estimated matrix seen in the approximate direct method, is the diagonal loading factor, and is the identity matrix of the appropriate size. It should be seen that this is meant to improve the standard SMI method where SMI uses a smaller number of range bins in its average than the standard SMI technique. Since fewer samples are used in the training data, the matrix often requires stabilization in the form of diagonal loading.[2]

More restrictive examples involve modeling the interference to force Toeplitz structures, and can greatly reduce the computational complexity associated with the processing by exploiting this structure.[2] However, these methods can suffer due to model-mismatch, or the computational savings may be undone by the problem of model fitting (such as the nonlinear problem of fitting to a Toeplitz or block-Toeplitz matrix) and order estimation.[2]

Modern applications

Despite nearly 40 years of existence, STAP has modern applications.

MIMO communications

For dispersive channels, multiple-input multiple-output communications can formulate STAP solutions. Frequency-selective channel compensation can be used to extend traditional equalization techniques for SISO systems using STAP.[5] To estimate the transmitted signal at a MIMO receiver, we can linearly weight our space-time input with weighting matrix as follows

to minimize the mean squared error (MSE).[5] Using STAP with a training sequence , the estimated optimal weighting matrix (STAP coefficients) is given by:[5]

MIMO radar

STAP has been extended for MIMO radar to improve spatial resolution for clutter, using modified SIMO radar STAP techniques.[9] New algorithms and formulations are required that depart from the standard technique due to the large rank of the jammer-clutter subspace created by MIMO radar virtual arrays,[9] which typically involves exploiting the block diagonal structure of the MIMO interference covariance matrix to break the large matrix inversion problem into smaller ones. In comparison with SIMO radar systems, which will have transmit degrees of freedom, and receive degrees of freedom, for a total of , MIMO radar systems have degrees of freedom, allowing for much greater adaptive spatial resolution for clutter mitigation.[9]

See also

- Array processing

- Beamforming

- MIMO

- Multistatic radar

- Phased array

- Synthetic aperture radar

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Melvin, W.L., A STAP Overview, IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine – Special Tutorials Issue, Vol. 19, No. 1, January 2004, pp. 19–35.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 Guerci, J.R., Space-Time Adaptive Processing for Radar, Artech House Publishers, 2003. ISBN 1-58053-377-9.

- ↑ Richards, M.A., Scheer, J.A., and Holm, W.A., Principles of Modern Radar, SciTech Publishing, 2010. ISBN 1-89112-152-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Richards, M.A., Fundamentals of Radar Signal Processing, McGraw-Hill Education, 2014. ISBN 0-07179-832-3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Bliss, D.W. and Govindasamy, S., Adaptive Wireless Communications: MIMO Channels and Networks, Cambridge University Press, 2013. ISBN 1-10703-320-9.

- ↑ Dudgeon, D.E. and Mersereau, R.M., Multidimensional Digital Signal Processing, Prentice-Hall Signal Processing Series, 1984. ISBN 0-13604-959-1.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Ward, J., Space-Time Adaptive Processing for Airborne Radar, IEE Colloquium on Space-Time Adaptive Processing (Ref. No. 1998/241), April 1998, pp. 2/1–2/6.

- ↑ Van Trees, H. L., Optimum Array Processing, Wiley, NY, 2002.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Li, J. and Stoica, P., MIMO Radar Signal Processing, John Wiley & Sons, 2009. ISBN 0-47017-898-1.

Further reading

- Brennan, L.E. and I.S. Reed, Theory of Adaptive Radar, IEEE AES-9, pp. 237–252, 1973

- Guerci, J.R., Space-Time Adaptive Processing for Radar, Artech House Publishers, 2003. ISBN 1-58053-377-9.

- Klemm, Richard, Principles of Space-Time Adaptive Processing, IEE Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0-85296-172-3.

- Klemm, Richard, Applications of Space-Time Adaptive Processing, IEE Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-85296-924-4.

- Melvin, W.L., A STAP Overview, IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine – Special Tutorials Issue, Vol. 19, No. 1, January 2004, pp. 19–35.

- Michael Parker, Radar Basics – Part 4: Space-time adaptive processing, EETimes, 6/28/2011

|