Place:Duchy of Poland (c. 960–1025)

Duchy of Poland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 960–1025 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

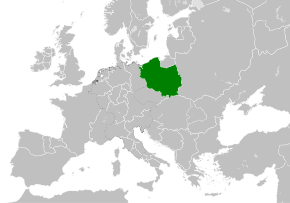

Duchy of Poland within Europe around 1000. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Gniezno | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Polish Latin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (institutional since 966) Slavic paganism (widely practiced) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Polish | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Patrimonial monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duke | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 960–992 (first) | Mieszko I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 992–1025 | Bolesław I the Brave | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | c. 960 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Christianization of Poland | 14 April 966 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Cornotion of Bolesław I the Brave | 1025 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 1000 | from 1 to 2 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Denar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | PL | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Duchy of Poland[lower-alpha 1] was a duchy in Central Europe with its capital being Gniezno. Its government system was patrimonial monarchy. The state was formed around 960. Mieszko I was crowned as the ruler of Polans between 950 and 960. The state took Christianity as its state religion in 966 durimng Christianization of Poland. The state existed until the coronation of Bolesław I the Brave for the king in 1025, who turned the duchy into the Kingdom of Poland.

The size of the state at its peak remains uncertain, but it included Lesser Poland, Greater Poland, Masovia, territories of Lechites as well as areas of land taken from Duchy of Bohemia.[1] The country is considered to be the earliest historic independent Polish state.[1]

History

The regin of Mieszko I

The tribe of the Polans in what is now Greater Poland gave rise to a tribal predecessor of the Polish state in the early part of the 10th century, with the Polans settling in the flatlands around the emerging strongholds of Giecz, Poznań, Gniezno and Ostrów Lednicki. Accelerated rebuilding of old tribal fortified settlements, construction of massive new ones and territorial expansion took place during the period ca. 920–950.[2] The Polish state developed from these tribal roots in the second half of the century. According to the 12th-century chronicler Gallus Anonymus, the Polans were ruled at this time by the Piast dynasty. In existing sources from the 10th century, Piast ruler Mieszko I was first mentioned by Widukind of Corvey in his Res gestae saxonicae, a chronicle of events in Germany. Widukind reported that Mieszko's forces were twice defeated in 963 by the Veleti tribes acting in cooperation with the Saxon exile Wichmann the Younger.[citation needed] Under Mieszko's rule (ca. 960 to 992), his tribal state accepted Christianity and became the Polish state.[3]

The viability of the Mieszko's emerging state was assured by the persistent territorial expansion of the early Piast rulers. Beginning with a very small area around Gniezno (before the town itself existed), the Piast expansion lasted throughout most of the 10th century and resulted in a territory approximating that of present-day Poland. The Polanie tribe conquered and merged with other Slavic tribes and first formed a tribal federation, then later a centralized state. After the addition of Lesser Poland, the country of the Vistulans, and of Silesia (both taken by Mieszko from the Czech state during the later part of the 10th century), Mieszko's state reached its mature form, including the main regions regarded as ethnically Polish.[citation needed] The Piast lands totaled about 250,000 km2 (96,526 sq mi) in area,[4] with an approximate population of under one million.[5]

Initially a pagan, Mieszko I was the first ruler of the Polans tribal union known from contemporary written sources. A detailed account of aspects of Mieszko's early reign was given by Ibrâhîm ibn Ya`qûb, a Jewish traveler, according to whom Mieszko was one of four Slavic "kings" established in central and southern Europe in the 960s.[6][7] In 965, Mieszko, who was allied with Boleslaus I, Duke of Bohemia at the time, married the duke's daughter Doubravka, a Christian princess. Mieszko's conversion to Christianity in its Western Latin Rite followed on 14 April 966,[8] an event known as the Baptism of Poland that is considered to be the founding event of the Polish state. In the aftermath of Mieszko's victory over a force of the Velunzani in 967, which was led by Wichmann, the first missionary bishop was appointed: Jordan, bishop of Poland. The action counteracted the intended eastern expansion of the Magdeburg Archdiocese, which was established at about the same time.[citation needed][9][10]

Mieszko's state had a complex political relationship with the German Holy Roman Empire, as Mieszko was a "friend", ally and vassal of Holy Roman Emperor Otto I and paid him tribute from the western part of his lands. Mieszko fought wars with the Polabian Slavs, the Czechs, Margrave Gero of the Saxon Eastern March in 963–964 and Margrave Odo I of the Saxon Eastern March in 972 in the Battle of Cedynia. The victories over Wichmann and Odo allowed Mieszko to extend his Pomeranian possessions west to the vicinity of the Oder River and its mouth. After the death of Otto I, and then again after the death of Holy Roman Emperor Otto II, Mieszko supported Henry the Quarrelsome, a pretender to the imperial crown. After the death of Doubravka in 977, Mieszko married Oda von Haldensleben, daughter of Dietrich, Margrave of the Northern March, ca. 980. When fighting the Czechs in 990, Mieszko was helped by the Holy Roman Empire. By about the year 990, when Mieszko I officially submitted his country to the authority of the Holy See (Dagome iudex), he had transformed Poland into one of the strongest powers in central-eastern Europe.[citation needed][10]

The reign of Bolesław I the Brave

When Mieszko I died in 992, he was succeeded by his son Bolesław contrary to his wishes. In order to ascend the throne, Bolesław had to contest it with his widowed stepmother Oda, his father's second wife, and her minor sons. Bolesław was Mieszko's oldest son, born to his first wife Doubravka of Bohemia, who died in 977. His father intended to divide the duchy of Poland between his sons, but Bolesław succeeded in displacing his stepmother and stepbrothers to become the sole ruler of Poland. Consistent with the intrigues he pursued at the start of his reign to secure his throne, Bolesław I Chrobry ("the Brave") proved himself to be a man of high ambition and strong personality.

One of the most important concerns of Bolesław's early reign was building up the Polish church. Bolesław cultivated Adalbert of Prague of the Slavník family, a well-connected Czech bishop in exile and missionary who was killed in 997 while on a mission in Prussia. Bolesław skillfully took advantage of his death: his martyrdom led to his elevation as patron saint of Poland and resulted in the creation of an independent Polish province of the Church with Radim Gaudentius as Archbishop of Gniezno. In the year 1000, the young Emperor Otto III came as a pilgrim to visit St. Adalbert's grave and lent his support to Bolesław during the Congress of Gniezno; the Gniezno Archdiocese and several subordinate dioceses were established on this occasion. The Polish ecclesiastical province effectively served as an essential anchor and an institution to fall back on for the Piast state, helping it to survive in the troubled centuries ahead.[11][12]

Bolesław at first chose to continue his father's policy of cooperation with the Holy Roman Empire but when Emperor Otto III died in 1002, Bolesław's relationship with his successor Henry II turned out to be much more difficult, and it resulted in a series of wars (1002–1005, 1007–1013, 1015–1018). From 1003 to 1004, Bolesław intervened militarily in Czech dynastic conflicts. After his forces were removed from Bohemia in 1018,[13] Bolesław retained Moravia.[14] In 1013, the marriage between Bolesław's son Mieszko and Richeza of Lotharingia, the niece of Emperor Otto III and future mother of Casimir I the Restorer, took place. The conflicts with Germany ended in 1018 with the Peace of Bautzen on favorable terms for Bolesław. In the context of the 1018 Kiev expedition, Bolesław took over the western part of Red Ruthenia. In 1025, shortly before his death, Bolesław I finally succeeded in obtaining the papal permission to crown himself, and he became the first king of Poland.[11][12]

Bolesław's expansionist policies were costly to the Polish state and were not always successful. He lost, for example, the economically crucial Farther Pomerania in 1005 together with its new bishopric in Kołobrzeg; the region had previously been conquered with great effort by Mieszko.[11][12]

List of rulers

- Mieszko I (c. 960–992)

- Bolesław I the Brave (992–1025)

See also

- Civitas Schinesghe

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Mieszko, Czcibor i...? Okoliczności śmierci zapomnianego brata pierwszego władcy Polski". https://histmag.org/Mieszko-Czcibor-i...-Okolicznosci-smierci-zapomnianego-brata-pierwszego-wladcy-Polski-21400/.

- ↑ Various authors, ed. Marek Derwich and Adam Żurek, U źródeł Polski (do roku 1038) (Foundations of Poland (until year 1038)), Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie, Wrocław 2002, ISBN:83-7023-954-4, Zofia Kurnatowska, pp. 147–149, Adam Żurek and Wojciech Mrozowicz, p. 226

- ↑ Various authors, ed. Marek Derwich and Adam Żurek, U źródeł Polski (do roku 1038) (Foundations of Poland (until year 1038)), pp. 144–159

- ↑ Francis W. Carter, Trade and urban development in Poland, Cambridge University Press, 1993, ISBN:0-521-41239-0, Google Print, p.47

- ↑ Jerzy Lukowski, Hubert Zawadzki, A Concise History of Poland, Cambridge University Press, 2001, ISBN:0-521-55917-0, Google Print, p.6

- ↑ Jerzy Wyrozumski, Dzieje Polski piastowskiej (VIII w. – 1370) (History of Piast Poland (8th century – 1370)), p. 77, Fogra, Kraków 1999, ISBN:83-85719-38-5

- ↑ Norman Davies, Europe: A History, p. 325, 1998 New York, HarperPerennial, ISBN:0-06-097468-0

- ↑ Kłoczowski, Jerzy (2000). A history of Polish Christianity. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-521-36429-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=ecdye8hk_tgC&pg=PA11. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ↑ Polski mogło nie być (There could have been no Poland) – an interview with the historian Tomasz Jasiński by Piotr Bojarski, Gazeta Wyborcza July 7, 2007

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Jerzy Wyrozumski, Historia Polski do roku 1505 (History of Poland until 1505), Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe (Polish Scientific Publishers PWN), Warszawa 1986, ISBN:83-01-03732-6, pp. 80–88

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Jerzy Wyrozumski, Historia Polski do roku 1505 (History of Poland until 1505), Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe (Polish Scientific Publishers PWN), Warszawa 1986, ISBN:83-01-03732-6, pp. 88–93

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Various authors, ed. Marek Derwich and Adam Żurek, U źródeł Polski (do roku 1038) (Foundations of Poland (until year 1038)), p. 168–183, Andrzej Pleszczyński

- ↑ Makk, Ferenc (1993). Magyar külpolitika (896-1196) ("The Hungarian External Politics (896-1196)"). Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. pp. 48–49. ISBN:963-04-2913-6.

- ↑ Ed. Andrzej Chwalba, Kalendarium dziejów Polski (Chronology of Polish History), p. 33, Krzysztof Stopka. Copyright 1999 Wydawnictwo Literackie Cracow, ISBN:83-08-02855-1.