Place:Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia

Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia Names in official languages

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1919–1920 | |||||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||||

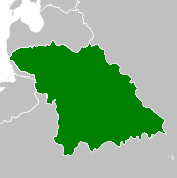

Map of the areas claimed by SSR Lithuania and Belorussia in 1920 (in Green). | |||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||||||

| Capital | Vilnius Minsk | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Belarusian · Lithuanian · Polish · Russian · Yiddish | ||||||||||

| Government | Socialist soviet republic | ||||||||||

• Chairman of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of Soviets | Kazimierz Cichowski | ||||||||||

• Chairman of Council of People's Commissars | Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||||

• Established | 27 February 1919 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 31 July 1920 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Ruble | ||||||||||

The Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia (SSR LiB),[note 1] alternatively referred to as the Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and White Russia or simply Litbel (Lit-Bel), was a Soviet republic that existed within the parts of the territories of modern Belarus and Lithuania for approximately five months during the Lithuanian–Soviet War and the Polish–Soviet War in 1919. The Litbel republic was created in February 1919 formally through the merger of the short-lived Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Socialist Soviet Republic of Belorussia.

Often described as a puppet state of Soviet Russia,[1][2][3] during its brief existence the SSR LiB government had limited authority over the territories it claimed. By August 1919, the SSR LiB had lost control over all of its claimed territories, as the Polish Army and, to a lesser extent, Lithuanian Army advanced.

History

Background

After the end of World War I in November 1918, Soviet Russia began a westward offensive following the retreating German Army. It attempted to spread the global proletarian revolution and sought to establish Soviet republics in Eastern Europe.[4] By the end of December 1918, Bolshevik forces reached Lithuania. The Bolsheviks saw the Baltic states as a barrier or a bridge into Western Europe, where they could join the German and the Hungarian Revolutions.[5]

The Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania was proclaimed on 16 December 1918[6] and the Socialist Soviet Republic of Belorussia (SSRB) was established on 1 January 1919.[7] On 16 January 1919, as the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (bolsheviks) issued two resolutions affecting the two new Soviet republics of the western frontier; one calling for the unification of Soviet Lithuania and Soviet Belorussia and the other calling for the transfer of the Vitebsk Governorate, the Smolensk Governorate and the Mogilev Governorate from the Belorussian Soviet republic to Soviet Russia.[8][9] On 22 January 1919 Adolph Joffe arrived in Minsk, as the representative of the Moscow centre with a mission to bring order among the infighting Bolshevik leadership in Belorussia.[8] The Belorussian Bolshevik leaders rejected the notion of merger with Lithuania and the detachment of the three eastern Belorussian governorates from the SSRB.[8] They protested to the RCP(b) Central Committee and decried that Joffe was incompetent.[8]

Minsk and Vilna congresses

The First All-Belorussian Congress of Soviets (be) was held in Minsk 2–3 February 1919.[9][10] The Central Executive Committee of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic (RSFSR) was represented at the congress by its chairman Yakov Sverdlov.[10] Prior to the opening of the congress the Belorussian Soviet leadership had, under pressure from the RCP(b), agreed to the bifurcation of their republic.[11] At the congress the delegations from Mogilev, Smolensk, Vitebsk withdrew from the proceedings, demanding that their governorates be re-integrated in the RSFSR.[12] The congress subsequently determined that the territory of the SSRB would be limited to the Minsk Governorate and the Grodno Governorate.[11] Effectively, considering the ongoing war, this move left the SSRB government in control of just six uyezds of Minsk Governorate.[12]

Sverdlov held a speech calling for unity between Soviet Belorussia and Soviet Lithuania, which he stated was a necessity to combat the 'White Army-Belorussian-Lithuanian government'.[8] He argued that a united Lithuanian-Belorussian state was a necessity to counter national-chauvinistic tendencies (including within the communist ranks).[8] As Sverdlov's proposal won majority support (especially from grassroot delegates), the congress tasked the Central Executive Committee of the SSRB to work for unification with the Lithuanian soviet republic.[8][11]

In a similar vein, the First Congress of Soviets of Lithuania, which met in Vilna (Vilnius, Wilno) from 18 to 20 February 1919 and was attended by 220 delegates, examined the report of the Lithuanian Provisional Worker-Peasant Government on the question of union with Belorussia. The congress agreed on union of the Lithuanian and Belorussian soviet republics and their federation with the Russian Soviet republic. The resolution of the Vilna congress read "[k]eenly conscious of our inseparable bond with all the Soviet Socialist Republics, the congress instructs the Workers' and Peasants' Government of the Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia to inaugurate negotiations forthwith with the workers' and peasants' governments of the R.S.F.S.R., Latvia, the Ukraine and Estonia with a view to constituting all these republics into a single R.S.F.S.R."[10]

Founding of the SSR LiB

On 27 February 1919, a Central Executive Committee of the Lithuanian Soviet Republic and the Central Executive Committees of the SSRB held a joint meeting in Vilna.[9] The meeting elected the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of Soviets of Lithuania and Belorussia it with Kazimierz Cichowski at its helm.[9] Furthermore, the meeting founded the Council of People's Commissars of the Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia as the government cabinet for the new united Soviet republic, headed by Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas.[9] The local communists leaders managed to resist the imposition that Joffe would become the head of the republic, albeit he remained in the area as the representative of the Moscow centre.[8]

Kapilyev (2020) notes that unlike their predecessors, this government was not labelled 'Provisional'.[9] The 27 February 1919 meeting reluctantly accepted separation of the Mogilev, Smolensk and Vitebsk governorates from Belorussia.[9] Vilna became the capital the new Lithuanian-Belorussian republic.[13][14] However, most SSR LiB government institutions would be based in Minsk or Smolensk.[8] At the time of its founding, the territories under the control of the new republic in the Minsk, Vilna and Kovno governorates had a combined population of about 4 million people.[15]

A unification congress of the Communist Party of Lithuania and Belorussia (Old Occupation) and the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Belorussia was held in Vilna 4–6 March 1919, merging the two parties under the name of the former.[16][17][18] On the agrarian front, the party unification congress decided against the break-up of confiscated estates.[19] Rather than partitioning the estates for redistribution to smallholder and landless peasants the party unification congress opted for the conversion of the estates into collective state farms, a decision that soured relationships between the peasantry and the party.[19][20]

Evacuation to Minsk

As the Polish army advanced towards Vilna, the Council of People's Commissars set up the Defense Council of the SSR LiB.[11] The situation in Vilna was chaotic, with the SSR LiB government holding as many as 16 meetings between 8 April and 15 April 1919.[8] Local Polish populations supported the Polish army offensive on Vilna, which lasted from 17 to 21 April 1919.[8]

The SSR LiB government was evacuated to Dvinsk on 21 April 1919.[9] The loss of the Litbel capital undermined morale of the communist movement in the region.[8] The Litbel republic made three unsuccessful attempts to retake Vilna from the Polish army.[8] On 28 April 1919 the government was moved to Minsk.[9] Minsk was named the new capital of the republic.[11] However the evacuation had not been done in an orderly manner, much of the materials and staff of the government institutions had been left behind in Vilna.[11] Once in Minsk the People's Commissariats would not embark on setting up new institutions, rather they assimilated the existing structures of the Minsk Provincial Revolutionary Committee into their own commissariats.[9]

Evacuation to Bobruisk

In May 1919, with the Polish forces advancing on Minsk, the Council of People's Commissars and some People's Commissariats withdrew to Bobruisk.[11] On 30 May 1919 the SSR LiB Central Executive Committee signed a treaty with the RSFSR government, remitting management of the SSR LiB military and economic affairs to the RSFSR government.[21] The Defense Council stayed in Minsk.[11] However, by mid-June the SSR LiB had lost control of even the peripheries of the city.[8] A number of anti-Soviet rebellions occurred in various parts of the lands claimed by the SSR LiB, with green armies taking hold of lands.[8]

On June 1, 1919, the Military-Political Union of Soviet Republics was announced at a festive meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee in Moscow.[22][23] A delegation of SSR LiB attended the meeting.[22] The union would consist of the RSFSR, SSR LiB, the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic, Latvian Socialist Soviet Republic and the Crimean Socialist Soviet Republic - per the decree issued at the meeting the republics would have a unified military organization and command, and the National Councils of Economy and Transportation and People's Commissariats of Labour of the Soviet republics would be merged.[22][23] Subsequently, the SSR LiB army was merged into the RSFSR armed forces on June 7, 1919.[23] On June 21, 1919, the SSR LiB Central Executive Committee issued a statement praising the Military-Political Union, calling a first step towards the unification of all Soviet republics.[23]

On 13 July 1919, Joseph Stalin , who had arrived to supervise the Western Front, proposed dissolving the SSR LiB Defense Council and Council of People's Commissars.[11] The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Lithuania and Belorussia opposed Stalin's proposition, arguing that the move would spell the end for the republic.[11] The RCP(b) Orgburo agreed to delay the disbanding of the SSR LiB Council of People's Commissars, but called for disbanding the Defense Council.[11] On 17 July 1919, at a joint meeting of the Central Executive Committee of the SSRLiB, the Minsk Soviet and the Central Council of Trade Unions took the decision to dissolve the Defense Council.[11][21] At this point Polish forces controlled about 75% of the territories claimed by SSR LiB.[16]

On 19 July 1919, the Central Executive Committee of SSR LiB decided to create Provisional Minsk Governorate Revolutionary Committee, entrusting it the authority to manage affairs in unoccupied territories.[11] The Council of People's Commissars ceased to function, with the Minsk Governorate Revolutionary Committee taking over its functions.[9][11] The SSR LiB People's Commissariats, now based in Bobruisk, were rebranded as departments of the Minsk Governorate Revolutionary Committee.[9][11] Nevertheless, the People's Commissariats maintained the orientation that they would function as government institutions for unoccupied parts of SSR LiB.[9]

Prisoner swaps

Following a decision by the SSR LiB Military-Revolutionary Committee, on April 2, 1919, a prisoner swap with the took place in Kaišiadorys, whereby the German Army released 24 prisoners (members of the Kovno Soviet of Workers Deputies and activists) in exchange for 13 detained members of the German delegation in Vilna (led by G. von Trützschler). On May 17, 1919 Mykolas Sleževičius (Prime Minister of the Republic of Lithuania) proposed an exchange of prisoners with the SSR LiB. SSR LiB agreed for negotiations, with Mickevičius-Kapsukas reportedly stated that the condition for the exchange would be 'one Lithuanian bourgeois hostage for two communists'. Negotiations between the SSR LiB and the Sleževičius government took place in three sessions in Novoalexandrovsk, June 25–26, 1919, July 3, 1919, and July 11, 1919. In the end the negotiations resulted in the release of 25 communist prisoners, including A. Drabavičiūtė, P. Svotelis-Proletaras, P. Marcinkutė, M. Juškevičius, M. Miliauskas, K. Matulaitytė, V. Bistrickas, E. Staškūtė, M. Kunickis, K. Keturaitis, J. Grigelis, M. Mickevičiūtė and V. Jakovickis.[24]

Fall of Minsk and Bobruisk

On 8 August 1919, Polish forces seized Minsk.[11] By 20 August 1919, the Polish forces reached the Berezina river.[11] On 28 August, the Soviet 16th Army withdrew from Bobruisk and entrenched themselves on the left bank of the Berezina river.[11] The Minsk Governorate Revolutionary Committee evacuated to Smolensk. In Smolensk the Minsk Governorate Revolutionary Committee ceased to function.[11] The authority to manage the unoccupied uyezds of the SSR LiB was transferred to the authorities of the Gomel Governorate and the Vitebsk Governorate.[11] Based on the erstwhile departments of the Minsk Governorate Revolutionary Committee the Liquidation Commission of the evacuated institutions of Lithuania and Belarus was set up.[11] On 27 August 1919 Polish forces seized Novoalexandrovsk, whereby the SSR LiB lost control over the last town in the territories claimed by the republic.[8] By September 1919 Polish-Soviet front had stabilized on along the line of the Western Dvina-Ptsich-Berezina rivers.[11]

Final stages of the republic

By September 1919, Soviet Russia had already recognized independent Lithuania and offered to negotiate a peace treaty.[6] By April 1920 Red Army began retaking Belorussia from Polish forces.[11] Based on a decision by the RCP(b) Politburo in May 1920, by July 1920 Revolutionary Military Council of the Western Front created Minsk Governorate Military Revolutionary Committee as the military and civil authority in the Belorussian lands retaken by the Red Army.[11] The Military Revolutionary Committee functioned as an organ of the RSFSR.[11]

On 11 July 1920, the Red Army seized Minsk.[11] The Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty was concluded on 12 July 1920.[11][7] A meeting of three parties - the Communist Party of Lithuania and Belorussia (represented by Vilhelm Knorin, Iosif Adamovich and Alexander Chervyakov), Vsevolod Ignatovsky's Belorussian Communist Organization and the General Jewish Labour Bund led by Arn Vaynshteyn - was held on 30 July 1920, which decided to reestablish a Belorussian Soviet republic.[16] The Belorussian Military Revolutionary Committee, which was to act as an emergency temporary authority in the Belorussian areas under Soviet control, was formed - consisting of Knorin, Adamovich, Chervyakov, I. Klishevsky, Ignatovsky, Vaynshteyn.[25] Klishevsky was named as the provisional secretary of the Belorussian Military Revolutionary Committee.[26] Participation of A. Trofimov of the Belorussian Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (ru) in the Belorussian Military Revolutionary Committee was foreseen.[26]

The next day, on 31 July 1920, the foundation of the Belorussian Socialist Soviet Republic (BSSR) was announced at a ceremony in Minsk.[11][16] The border between the Poland and the BSSR was eventually determined by the 1921 Peace of Riga, which left territories with significant Belorussian populations on the Polish side of the border.[7]

Government

Formally the SSR LiB was a sovereign state.[8] However the actual role of governance of the SSR LiB government was limited. Per Kapliyev (2020) the SSR LiB government was "formed with the participation of local politicians, but were in fact fully controlled from Moscow. [...] The statehood of LitBel had mostly a propaganda character, and only formal trappings of an independent state."[9] Joffe, as the representative of the Moscow centre, hand-picked many of the key government members whilst some nominations were identified by the RCP(b) Central Committee directly.[8] The process of forming the government was characterized by tension between Joffe and local communists, as the former didn't promote cadres from the local intelligentsia and seemingly punished local leaders that had resisted the unification of the Lithuanian and Belorussian Soviet republics by overlooking them for key posts.[8] In the SSR LiB government bodies Lithuanians outnumbered Belorussians, the latter generally restricted to second-tier posts.[8]

The republic had five official languages; Russian, Belorussian, Lithuanian, Polish and Yiddish.[13][27] De facto Russian was the predominant language in public affairs, notably being the language of the Red Army soldiers.[13]

Central Executive Committee

At the 27 February 1919 meeting, the 100-member Central Executive Committee of Soviets of Worker, Smallholder and Landless Peasant and Red Army Deputies of the Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia was named the highest authority of government of the republic.[11][28] 91 out of the 100 members of the Central Executive Committee were communists.[29] The Central Executive Committee elected a Presidium with Kazimierz Cichowski as its chairman and Józef Unszlicht as its deputy chairman.[30][28] Other members of the Presidium were Yakov Doletsky, R.V. Pikel (ru), Pranas Svotelis-Proletaras and S.V. Ivanov (ru).[30][28]

People's Commissariats

At the time of the founding of the republic, People's Commissariats for Foreign Affairs, Internal Affairs, Agriculture, Communications, Education, Finance, Food, Labour, Justice, Post & Telegraphs, Military Affairs and the Supreme Council for People's Economy were created.[9][11] The following day the Council of People's Commissars decided to create two new People's Commissariats; Health Care and Social Protection by removing these areas from the responsibility of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs.[9] The People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs was inactive.[11] Several other People's Commissariats (such as the commissariats for Military Affairs, Information, Post & Telegraphs, etc., were managed directly by the RSFSR People's Commissariats).[11]

Members of the Council of the People's Commissars (equivalent to a cabinet of ministers) as of 27 or 28 February 1919 were;

- Chairman and Commissar for Foreign Affairs: Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas[30][28]

- Commissar for Internal Affairs: Zigmas Aleksa-Angarietis[30][28]

- Commissar of Food: Moses Kalmanovich (ru)[30][28]

- Commissar for Labor: Semyon Dimanstein[30][28]

- Commissar for Post & Telegraphs: Karl Rozental[30][28]

- Commissar for Information: I. P. Savitskty[30][28]

- Commissar for Justice: Mieczysław Kozłowski[30][28]

- Commissar for Military Affairs: Józef Unszlicht[30][28][31]

- Commissar for Education: Julian Leszczyński[30][28][31] (Vaclovas Biržiška, who had been the People's Commissar for Education in the Lithuanian soviet government, was named Deputy Commissar for Education)[32]

- Commissar for Finance: Yitzhak Weinstein-Branovsky[28]

- Commissar for Council of People's Economy: Vladimir Ginzburg (ru)[28]

- Commissar for Health (acting): Petras Avižonis[28][33]

- Commissar for Social Protection (acting): Josif Oldak[28][33]

- Commissar for Agriculture (acting): Vaclovas Bielskis (lt)[28][33]

- Commissar for State Control (acting): S. I. Berson (be)[30][34][33]

Defense Council

The SSR LiB Defense Council formed on 19 April 1919, included Mickevičius-Kapsukas (chairman) Unszlicht and Kalmanovich.[35] It was later expanded to include Cichowski, Knorin and Yevgenia Bosch.[35] The SSR LiB Defense Council worked under the guidance of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Lithuania and Belorussia, which had Mickevičius-Kapsukas as its chairman and Knorin as its secretary.[36]

Prominent participants in the activities of the SSR LiB Defense Council included Waclaw Bogucki, Victor Yarkin (ru), Yan Perno (ru), Aleksa-Angarietis, Doletsky and Ivanov.[36]

Administrative divisions

The republic sought to govern the Vilna Governorate, the Kovno Governorate, the Minsk Governorate, Grodno Governorate (except the Belostoksky Uyezd, the Belsky Uyezd and the Sokolsky Uyezd) and the Suvalsky Governorate (except the Avgustovsky Uyezd (ru) and the Suvalsky Uyezd (ru)) - territories with a total population of about six million.[11][16][37] On 16 April 1919 the Rechitsky Uyezd of Minsk Governorate was transferred to the RSFSR.[37]

Only the Minsk Governorate had a provincial-level administration.[11] The Minsk Governorate Military Revolutionary Committee (Mingubvoyenrevkom) was set-up as the provincial-level government for Minsk Governorate and Vileysky Uyezd (which had belonged to the Vilna Governorate).[11] Other governorates had only Military Commissariats at provincial level.[11] Mingubvoyenrevkom had its own commissariats.[11] Moreover, the Mingubvoyenrevkom would often by-pass the SSR LiB government and deal directly with the RSFSR Council of People's Commissars.[11] The Mingubvoyenrevkom was abolished once the SSR LiB capital was moved to Minsk.[11]

Apart from the areas governed by the Mingubvoyenrevkom during the first weeks of the SSR LiB, uyezd administrations were supervised directly by the SSR LiB government.[11] Local governments functioned along an uyezd-volost-village soviet scheme.[11] After the evacuation of the SSR LiB government to Minsk the supervision of city and uyezd administrations were managed directly by the Defense Council.[11]

State symbols

The Council of People's Commissars adopted a plain red cloth as the merchant and military flag of the republic.[38] Furthermore, the Council of People's Commissars decreed that the coat of arms of the republic would be identical to that of the RSFSR except with the exception that the symbol would include the initials 'SSR L and B' in five languages.[38] Per the draft constitution of the republic the coat of arms would included "a golden hammer and sickle in the rays of the rising sun against a red background, surrounded by a wreath of ears with the inscription in five languages : Lithuanian, Polish, Yiddish, Russian and Belorussian".[38]

Economy

The economy of the short-lived republic was in distress.[8] War, German occupation and population displacements had disrupted industrial and agricultural production, in the weeks preceding the foundation of the republic famine prevailed in the area.[8] Seeking to revive production, the SSR LiB government implemented a policy of war communism.[8] Nationalizations had begun with of factories with absentee owners in January–February 1919, eventually all economic activities were nationalized.[8]

The local peasantry rejected confiscations and resisted cooperation with the soviet authorities.[8] The Communist Party deployed military and paramilitary forces to seize farm produce to counter the food shortage in the cities, further aggravating hostilities between the government and the agrarian sectors.[8] By June 1919 famine prevailed in the republic.[8] In spite of the local food shortages the SSR LiB was pressured by the RSFSR to provide food supplies to Soviet Russia and the Red Army, which caused tensions between the leaderships of the two soviet republics.[8]

Army

The Lithuanian-Belorussian Army (be), designated as the armed forces of the SSR LiB, was formed on 13 March 1919 on the basis of the Russian Western Army.[39][40][41] It included the 8th Rifle Division, the 2nd Frontier Division, the 17th Rifle Division, the 52nd Rifle Division and, between March–April 1919, the Lithuanian Rifle Division.[39][41] The Lithuanian-Belorussian Army fought against Polish and German forces.[41]

In March 1919 the SSR LiB government issued a decree calling for mandatory conscription of all males aged 18 to 40, as well as mandatory labour for production.[8] The conscription decree was met with resistance from local populations, and could not be fully implemented.[8] The Lithuanian-Belorussian Army suffered massive desertions, as of June 1919 it was reported that there were some 33,000 deserters from the soviet military in the Minsk Governorate.[8]

Andrei Snesarev served as the commander of the Lithuanian-Belorussian Army until 31 May 1919.[41] Filipp Mironov served as acting commander until 9 June 1919.[41] A. N. Novikov served as the Chief of Staff of the Army.[41] On 9 June 1919 the Lithuanian-Belorussian Army was converted into the 16th Army of the Workers and Peasants Red Army.[39][42]

Culture

As the Red Army had seized Vilna, the Moscow centre directed much of the Jewish Commissariat (Evkom) staff to move to the new Litbel capital to win over the Yiddishist intelligentsia there.[43] Daniel Charney, under supervisor of Commissar S. G. Tomsinsky (ru), was charged with overseeing Yiddish-language cultural activities; attempting to reorganize a central Soviet Yiddish library (gathering materials from expropriated archives), publishing Yiddish language educational and cultural periodicals and absorbing the Vilna Troupe into an SSR LiB Yiddish state theatre.[43][44]

Historiography

Puppet, paper or buffer state?

Different historians have provided different explanations as to why the SSR LiB was founded.[12] At the time of the February 1919 All-Belorussian Congress of Soviets the sole official justification rationale provided for the merger of the Lithuanian and Belorussian soviet republics was a vague commentary in the congress declaration about the 'historical identity of economic interests' of Lithuania and Belorussia, without any mention of ethnicity or nationality.[12][16]

Several historians frame the Litbel experience as a failed attempt to create a Soviet Russian puppet state along its western border; the term 'puppet state' has been used by Piotr Łossowski, David R. Marples, Per Anders Rudling, Jerzy Borzęcki (pl), etc.[8] Dorota Michaluk describes the republic as a 'paper state'.[8] Alfonsas Eidintas (1999) writes that "Litbel's tenuous authority extended only as far as the Red Army advanced. It was an artificial creation that had little to do with the new realities on the ground, and it was stillborn."[1] Jan Zaprudnik emphasized that the creation of the Litbel republic was a move done by Soviet Russia in the view of territorial competition with Poland over Lithuania and Belorussia.[12] In a similar vein Richard Pipes claimed that the Litbel republic was "a mere device for Soviet expansion".[12]

Soviet historiography described the creation of the Litbel republic as a defensive measure against counter-revolutionaries whilst also stressing historical-cultural links between Lithuania and Belorussia.[12] Sergey Margunsky claimed in 1958 that Lenin himself had been the architect of the union between Lithuania and Belorussia, but without presenting any evidence.[8] The hypothesis that Lenin stood behind the idea of setting up the Litbel republic was reinforced in the 1980s, as Rostislav Plantinov (be) and Nikolay Stashkevich (ru) presented research on correspondence of late 1918.[8] By contrast, Smith (1999) argues that the creation of the Litbel republic remains something of an enigma as there no evidence in secondary sources regarding the rationale behind the foundation of the republic.[12] Per Smith, Joffe had been given a mandate to promote mergers between soviet republics (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, etc.) but that there is no evidence that the Moscow centre had ordered the creation of a specifically Lithuanian-Belorussian soviet republic (with mergers with Soviet Ukraine, Latvia or RSFSR having been equally plausible options).[12] For Smith it is possible the Soviet leadership intended to incorporate Poland as well within the republic.[12]

Borzęcki (2008), writing about the foundation of the Litbel republic, states that "[i]n contrast to the alacrity with which all previous Moscow's orders had been carried out, this one was acted upon with uncharacteristic tardiness. While Soviet Lithuania was unenthusiastic about the merger, Soviet Belarus was especially reluctant to participate in it. Moscow, however, continued to apply great pressure. [...] [Joffe] personally selected the members of Litbel's government, although they had to be approved by Moscow. Minsk's reluctance is explained by the merger terms, amounting to the annexation of what was left of Soviet Belarus by Soviet Lithuania."[13] Borzęcki argues that there were no ethnic Belorussians in the Litbel government.[13]

Multinational republic and Grand Duchy nostalgia

Mertelsmann (2003) argues that in creating a multi-ethnic republic "Litbel can be understood as an experiment to create a form of state organization beyond old national patterns", but affirms that such experiments would later become impossible with the ascendance of Stalin's approach to the national question as official Soviet policy, whereby each nation would be assigned separate statehood.[14]

Nicholas Vakar argued that the Litbel republic represented a compromise between separatists, federalists, and supporters of a Lithuanian-Belorussian state.[12] Hélène Carrère d'Encausse argued that logic behind the launch of Litbel was the creation of a state with a predominately pro-Russian population whereby the Lithuanian drive for independence would be contained, Lithuania would be removed from the British sphere of influence and pro-Polish tendencies would be undermined.[12]

Lundén (2006) states that the creation of the Litbel republic sought to incorporate both Belorussian and Lithuanian national aspirations, noting that Vilna had overlapping claims by Lithuanian, Belorussian and Polish nationalists.[45] Smith affirms that as the Vilnius region was ethnically diverse and contested between competing nationalisms, by creating a joint Litbel republic the Soviet leadership could avoid assigning Vilna to neither Lithuania nor Belorussia.[12]

Jahn (2009) argues that "the Lithuanian-Belarusian Republic (Litbel), which only existed for a few months in 1919, was even presented as a revival of the medieval Grand Principality."[46] Smith (1999) also highlights the possibility of nostalgia over the Grand Duchy of Lithuania having functioned as a rationale for Litbel, noting that as of 1915 the idea of a Lithuanian-Belorussian union had championed by Belorussian nationalists with German backing and that such a union could have been perceived as having a potential to attract support from nationalist trends.[12]

The end of the republic

Even the end of the republic is a source of dispute between historians. There are different viewpoints regarding the end date of the republic.[8] Some historians refer to Stalin's telegram to Lenin asking for the disbanding of the SSR LiB government and Defense Council as the end of the republic.[8] Per Borzęcki, Lenin liquidated SSR LiB on 17 July 1919 but the republic continued to exist formally until 1920.[8] After the loss of its claimed territories the administration of the republic was placed in a hibernation of sorts.[8] By late 1919 the sole SSR LiB government institution remaining operational were the agricultural representatives of the SSR LiB Council of People's Commissars.[21] There is no formal declaration or similar document from Lenin's side dissolving the republic.[8] Soviet historiography identified 31 July 1920 (i.e. being replaced by the BSSR) as the end date of SSR LiB.[47] Smith argues that the SSR LiB might have been retained as a formality until 1921.[8]

See also

- History of Belarus

- History of Lithuania

- Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (1940–1991)

- Republics of the Soviet Union

Notes

- ↑

- Belarusian: Сацыялістычная Савецкая Рэспубліка Літвы і Беларусі

- Lithuanian: Lietuvos ir Baltarusijos socialistinė tarybų respublika;

- Polish: Litewsko-Białoruska Socjalistyczna Republika Rad

- Russian: Социалистическая Советская Республика Литвы и Белоруссии, abbreviated as SSR LiB

- Yiddish: סאָציאַליסטישער סאָוועטישער רעפובליק פון ליטע און ווײַסרוסלאַנד.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Eidintas, Alfonsas; Vytautas Žalys; Alfred Erich Senn (September 1999). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918–1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 66. ISBN 0-312-22458-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=0_i8yez8udgC&pg=PA66.

- ↑ Kapliyev, Alexey A. (9 December 2020). "The Formation of Authorities of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Lithuania and Belarus on the Example of the People's Commissariat for Health Care at the Beginning of 1919.". Lithuanian Historical Studies 24 (1): 61–74. doi:10.30965/25386565-02401003. https://etalpykla.lituanistikadb.lt/object/LT-LDB-0001:J.04~2020~1610810813729/J.04~2020~1610810813729.pdf. "The governments were formed with the participation of local politicians, but were in fact fully controlled from Moscow. <...> The statehood of LitBel had mostly a propaganda character, and only formal trappings of an independent state.".

- ↑ "Lietuvos ir Baltarusijos SSR" (in lt). Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia. https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/lietuvos-ir-baltarusijos-ssr/. "Lietuvõs ir Baltarùsijos SSR, marionetinis valstybinis darinys, gyvavęs 1919 02–09."

- ↑ Davies, Norman (1998). Europe: A History. HarperPerennial. p. 934. ISBN 0-06-097468-0. https://archive.org/details/europehistory00norm/page/934.

- ↑ Rauch, Georg von (1970). The Baltic States: The Years of Independence. University of California Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-520-02600-4.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Suziedelis, Saulius (2011). Historical Dictionary of Lithuania (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-0-8108-4914-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=VkGB1CSfIlEC&pg=PA169.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Marples, David R. (1999). Belarus: a denationalized nation. Taylor & Francis. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-90-5702-343-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=EMCYfOSaLSgC&pg=PA5.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 8.20 8.21 8.22 8.23 8.24 8.25 8.26 8.27 8.28 8.29 8.30 8.31 8.32 8.33 8.34 8.35 8.36 8.37 8.38 8.39 8.40 Stanisław Boridczenko (2020). A Buffer for Soviet Russia: A Brief History of the Litbel, Revolutionary Russia, 33:1, 88-105, DOI: 10.1080/09546545.2020.1753288

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 Kapliyev, A. A. (2020). The Formation of Authorities of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Lithuania and Belarus on the Example of the People's Commissariat for Health Care at the Beginning of 1919, Lithuanian Historical Studies, 24(1), 61-74. doi: https://doi.org/10.30965/25386565-02401003

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 J. V. Stalin. The Government's Policy on the National Question. 31 January 1919

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 11.17 11.18 11.19 11.20 11.21 11.22 11.23 11.24 11.25 11.26 11.27 11.28 11.29 11.30 11.31 11.32 11.33 11.34 11.35 11.36 11.37 11.38 11.39 11.40 11.41 S. S. Rudovich. Создание советского государственного аппарата в Беларуси (1917—1920 гг.) in Белорусский археографический ежегодник, Issue 17 (2016). Minsk. pp. 63-92

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 J. Smith (13 January 1999). The Bolsheviks and the National Question, 1917–23. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-0-230-37737-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=pSZ9DAAAQBAJ&pg=PA74.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Jerzy Borzecki (1 October 2008). The Soviet-Polish Peace of 1921 and the Creation of Interwar Europe. Yale University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-300-14501-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=wjsk1sdZzdIC&pg=PA16.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Olaf Mertelsmann (2003). The Sovietization of the Baltic States, 1940-1956. KLEIO Ajalookirjanduse Sihtasutus. p. 99. ISBN 978-9985-9304-1-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=2YRpAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ П. Г Чигринов (2004) (in ru). История Беларуси с древности до наших дней : учебное пособие. Книжный Дом. pp. 486. ISBN 9789854288048. https://books.google.com/books?id=fw4hAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Per Anders Rudling (15 January 2015). The Rise and Fall of Belarusian Nationalism, 1906–1931. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 112–114, 128. ISBN 978-0-8229-7958-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=rRrRBgAAQBAJ&pg=PT112.

- ↑ Witold S. Sworakowski (1973). World Communism; a Handbook, 1918-1965. Hoover Institution Press. pp. 37, 309, 526. ISBN 978-0-8179-1081-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=P81mAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Vytas Stanley Vardys (1965). Lithuania Under the Soviets: Portrait of a Nation, 1940-65. Praeger. p. 112. https://books.google.com/books?id=ABlpAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Russian Studies in History. M.E. Sharpe, Incorporated. 1990. p. 74. https://books.google.com/books?id=f-4kAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Diana Siebert (1998). Bäuerliche Alltagsstrategien in der belarussischen SSR (1921-1941): die Zerstörung patriarchalischer Familienwirtschaft. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 44, 47. ISBN 978-3-515-07263-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=4dthRJdKK2UC&pg=PA47.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Vitaŭt Kipelʹ; Zora Kipel (1988). Byelorussian Statehood: Reader and Bibliography. Byelorussian Institute of Arts and Sciences. p. 188. https://books.google.com/books?id=DetoAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Andreĭ Antonovich Grechko (1975). The Armed Forces of the Soviet State: A Soviet View. [Department of Defense], Department of the Air Force. pp. 109. OCLC 3043559. https://books.google.com/books?id=EzuCy_h3PQwC&pg=PA109.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Tihomirov, A. V. ВЗАИМООТНОШЕНИЯ БССР И РСФСР В 1919-192 1 гг.: ПРОТИВОРЕЧИВОЕ ПАРТНЕРСТВО

- ↑ Bronius Vaitkevičius. Socialistinė revoliucija Lietuvoje 1918-1919 metais. Mintis, 1967. p. 627

- ↑ П. Г Чигринов (2000) (in ru). Очерки истории Беларуси. Вышэйшая Школа. pp. 326. ISBN 9789850605467. https://books.google.com/books?id=4u4iAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Okti︠a︡brʹ 1917 i sudʹby politicheskoĭ oppozit︠s︡ii: U istokov politicheskogo protivostoi︠a︡nii︠a︡. Belorusskoe Agenstvo nauch.-tekhn. i delovoĭ informat︠s︡ii, 1993. p. 187

- ↑ Alfred Abraham Greenbaum (1988). Minority Problems in Eastern Europe Between the World Wars: With Emphasis on the Jewish Minority. Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Institute for Advanced Studies. p. 46. https://books.google.com/books?id=TcMMAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 28.00 28.01 28.02 28.03 28.04 28.05 28.06 28.07 28.08 28.09 28.10 28.11 28.12 28.13 28.14 28.15 28.16 Vadim Andreevich Krutalevich (2007). Ocherki istorii gosudarstva i prava Belarusi. Pravo i ėkonomika. p. 124. ISBN 978-985-442-395-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=d_UiAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Евгения Никифоровна Шкляр (1962). Борьба трудящихся Литовско-Белорусской ССР с иностранными интервентами и внутренней контрреволюцией, 1919-1920 гг. Гос. изд-во Бсср. p. 35. https://books.google.com/books?id=wqMbAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 30.00 30.01 30.02 30.03 30.04 30.05 30.06 30.07 30.08 30.09 30.10 30.11 Белорусская ССР, краткая энциклопедия: История. Общественный и государственный строй. Законодательство и право. Административно-территориальное устройство. Населенные пункты. Международные связи. Белорус. сов. энциклопедия. 1979. p. 359. https://books.google.com/books?id=Qp8cAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Norman Davies (1972). White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919-20. Macdonald and Company. pp. 280, 283. ISBN 978-0-356-04013-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=2ES0AAAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Lituanus. Lithuanian Student Association, Secretariate for External Relations. 1975. p. 58. https://books.google.com/books?id=GUk8AAAAIAAJ.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 S. P. Margunskiĭ (1970). История государства и права Белорусской ССР: 1917-1936 гг. Наука и техника. pp. 75, 595. https://books.google.com/books?id=wlUHAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Іван Шамякін (1983). Минск: энциклопедический справочник. Izd-vo "Belorusskai︠a︡ sov. ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡" im. Petrusi︠a︡ Brovki. p. 98. https://books.google.com/books?id=YEAdAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 60 [i.e. Shestʹdesi͡a︡t] geroicheskikh let: 1918-1978 : stikhi. Voenizdat. 1978. p. 30. https://books.google.com/books?id=KLtKAAAAYAAJ.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Коммунист Белоруссии. Звязда. 1963. p. 76. https://books.google.com/books?id=VcohAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Геннадий Владимирович Ридевский (2007). Территориальная организация Республики Беларусь: социально-эколого-экономическая модель перехода к устойчивому развиитю : монография. МГУ им. А.А. Кулешова. p. 109. ISBN 978-985-480-318-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=KjkUAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Flag Bulletin. Flag Research Center.. 1988. p. 108. https://books.google.com/books?id=7jIrAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Report on the USSR.. RFE/RL, Incorporated. April 1990. p. 8. https://books.google.com/books?id=aPNoAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Андрей Михайлович Буровский (2010). Самая страшная русская трагедия: правда о Гражданской войне. Яуза-пресс. p. 265. ISBN 978-5-9955-0152-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=WnM3AQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 41.5 Jonathan D. Smele (19 November 2015). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916-1926. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 681. ISBN 978-1-4422-5281-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=QwquCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA681.

- ↑ Belaruskai︠a︡ SSR: Historyi︠a︡. Hramadski i dzi︠a︡rshaŭny lad. Zakanadaŭstva i prava. Administratsyĭna-terytaryi︠a︡lʹny padzel, naselenyi︠a︡ punkty. Mizhnarodnyi︠a︡ suvi︠a︡zi. Haloŭnai︠a︡ rėdaktsyi︠a︡ Belaruskaĭ Savetskaĭ Ėntsyklapedyi. 1978. p. 711. https://books.google.com/books?id=k-kEAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Kenneth B. Moss (28 February 2010). Jewish Renaissance in the Russian Revolution. Harvard University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-674-05431-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=cHE1RO7cq2AC&pg=PA228.

- ↑ Kenneth Benjamin Moss (2003). 'A Time for Tearing Down and a Time for Building Up': Recasting Jewish Culture in Eastern Europe, 1917-1921. Stanford University. p. 303. https://books.google.com/books?id=5ldEAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Thomas Lundén (2006). Crossing the Border: Boundary Relations in a Changing Europe. Förlags ab Gondolin. p. 54. ISBN 978-91-85629-03-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=ptEMAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Egbert Jahn (January 2009). Nationalism in Late and Post-Communist Europe. Nomos. p. 216. ISBN 978-3-8329-3969-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=1mgNAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Вопросы истории КПСС: орган Института марксизма-ленинизма при ЦК КПСС. Изд-во "Правда". 1962. p. 190. https://books.google.com/books?id=o04KAAAAIAAJ.

Further reading

|