Position weight matrix

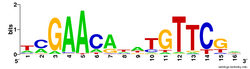

A position weight matrix (PWM), also known as a position-specific weight matrix (PSWM) or position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM), is a commonly used representation of motifs (patterns) in biological sequences.

PWMs are often derived from a set of aligned sequences that are thought to be functionally related and have become an important part of many software tools for computational motif discovery.

Background

Creation

Conversion of sequence to position probability matrix

A PWM has one row for each symbol of the alphabet (4 rows for nucleotides in DNA sequences or 20 rows for amino acids in protein sequences) and one column for each position in the pattern. In the first step in constructing a PWM, a basic position frequency matrix (PFM) is created by counting the occurrences of each nucleotide at each position. From the PFM, a position probability matrix (PPM) can now be created by dividing that former nucleotide count at each position by the number of sequences, thereby normalising the values. Formally, given a set X of N aligned sequences of length l, the elements of the PPM M are calculated:

where i (1,...,N), j (1,...,l), k is the set of symbols in the alphabet and I(a=k) is an indicator function where I(a=k) is 1 if a=k and 0 otherwise.

For example, given the following DNA sequences:

GAGGTAAAC

TCCGTAAGT

CAGGTTGGA

ACAGTCAGT

TAGGTCATT

TAGGTACTG

ATGGTAACT

CAGGTATAC

TGTGTGAGT

AAGGTAAGT

The corresponding PFM is:

Therefore, the resulting PPM is:[1]

Both PPMs and PWMs assume statistical independence between positions in the pattern, as the probabilities for each position are calculated independently of other positions. From the definition above, it follows that the sum of values for a particular position (that is, summing over all symbols) is 1. Each column can therefore be regarded as an independent multinomial distribution. This makes it easy to calculate the probability of a sequence given a PPM, by multiplying the relevant probabilities at each position. For example, the probability of the sequence S = GAGGTAAAC given the above PPM M can be calculated:

Pseudocounts (or Laplace estimators) are often applied when calculating PPMs if based on a small dataset, in order to avoid matrix entries having a value of 0.[2] This is equivalent to multiplying each column of the PPM by a Dirichlet distribution and allows the probability to be calculated for new sequences (that is, sequences which were not part of the original dataset). In the example above, without pseudocounts, any sequence which did not have a G in the 4th position or a T in the 5th position would have a probability of 0, regardless of the other positions.

Conversion of position probability matrix to position weight matrix

Most often the elements in PWMs are calculated as log odds. That is, the elements of a PPM are transformed using a background model so that:

describes how an element in the PWM (left), , can be calculated. The simplest background model assumes that each letter appears equally frequently in the dataset. That is, the value of for all symbols in the alphabet (0.25 for nucleotides and 0.05 for amino acids). Applying this transformation to the PPM M from above (with no pseudocounts added) gives:

The entries in the matrix make clear the advantage of adding pseudocounts, especially when using small datasets to construct M. The background model need not have equal values for each symbol: for example, when studying organisms with a high GC-content, the values for C and G may be increased with a corresponding decrease for the A and T values.

When the PWM elements are calculated using log likelihoods, the score of a sequence can be calculated by adding (rather than multiplying) the relevant values at each position in the PWM. The sequence score gives an indication of how different the sequence is from a random sequence. The score is 0 if the sequence has the same probability of being a functional site and of being a random site. The score is greater than 0 if it is more likely to be a functional site than a random site, and less than 0 if it is more likely to be a random site than a functional site.[1] The sequence score can also be interpreted in a physical framework as the binding energy for that sequence.

Information content

The information content (IC) of a PWM is sometimes of interest, as it says something about how different a given PWM is from a uniform distribution.

The self-information of observing a particular symbol at a particular position of the motif is:

The expected (average) self-information of a particular element in the PWM is then:

Finally, the IC of the PWM is then the sum of the expected self-information of every element:

Often, it is more useful to calculate the information content with the background letter frequencies of the sequences you are studying rather than assuming equal probabilities of each letter (e.g., the GC-content of DNA of thermophilic bacteria range from 65.3 to 70.8,[3] thus a motif of ATAT would contain much more information than a motif of CCGG). The equation for information content thus becomes

where is the background frequency for letter . This corresponds to the Kullback–Leibler divergence or relative entropy. However, it has been shown that when using PSSM to search genomic sequences (see below) this uniform correction can lead to overestimation of the importance of the different bases in a motif, due to the uneven distribution of n-mers in real genomes, leading to a significantly larger number of false positives.[4]

Uses

There are various algorithms to scan for hits of PWMs in sequences. One example is the MATCH algorithm[5] which has been implemented in the ModuleMaster.[6] More sophisticated algorithms for fast database searching with nucleotide as well as amino acid PWMs/PSSMs are implemented in the possumsearch software.[7]

The basic PWM/PSSM is unable to deal with insertions and deletions. A PSSM with additional probabilities for insertion and deletion at each position can be interpreted as a hidden Markov model. This is the approach used by Pfam.[8][9]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Guigo, Roderic. "An Introduction to Position Specific Scoring Matrices". bioinformatica.upf.edu. http://bioinformatica.upf.edu/T12/MakeProfile.html. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ↑ Nishida, K.; Frith, M. C.; Nakai, K. (23 December 2008). "Pseudocounts for transcription factor binding sites". Nucleic Acids Research 37 (3): 939–944. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn1019. PMID 19106141.

- ↑ Aleksandrushkina NI, Egorova LA (1978). "Nucleotide makeup of the DNA of thermophilic bacteria of the genus Thermus". Mikrobiologiia 47 (2): 250–2. PMID 661633.

- ↑ Erill I, O'Neill MC (2009). "A reexamination of information theory-based methods for DNA-binding site identification". BMC Bioinformatics 10: 57. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-10-57. PMID 19210776.

- ↑ "MATCHTM: a tool for searching transcription factor binding sites in DNA sequences". Nucleic Acids Research 31 (13): 3576–3579. 2003. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg585. PMID 12824369.

- ↑ Wrzodek, Clemens; Schröder, Adrian; Dräger, Andreas; Wanke, Dierk; Berendzen, Kenneth W.; Kronfeld, Marcel; Harter, Klaus; Zell, Andreas (9 October 2009). "ModuleMaster: A new tool to decipher transcriptional regulatory networks". Biosystems 99 (1): 79–81. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2009.09.005. ISSN 0303-2647. PMID 19819296.

- ↑ Beckstette, M. et al. (2006). "Fast index based algorithms and software for matching position specific scoring matrices". BMC Bioinformatics 7: 389. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-7-389. PMID 16930469.

- ↑ Kim, Seyoung; Chikina, Maria. "PSC103 Spring 2016 / HMMs and biological sequence analysis". https://www.csb.pitt.edu/ComputationalGenomics/Lectures/Lec5.pdf.

- ↑ "What are profile hidden Markov models?" (in en). https://www.ebi.ac.uk/training/online/courses/pfam-creating-protein-families/what-are-profile-hidden-markov-models-hmms/.

External links

- 3PFDB – a database of Best Representative PSSM Profiles (BRPs) of Protein Families generated using a novel data mining approach.

- UGENE – PSS matrices design, integrated interface to JASPAR, UniPROBE and SITECON databases.

|