Quantum Secret Sharing

Quantum secret sharing (QSS) is a quantum cryptographic scheme for secure communication that extends beyond simple quantum key distribution. It modifies the classical secret sharing (CSS) scheme by using quantum information and the no-cloning theorem to attain the ultimate security for communications.

The method of secret sharing consists of a sender who wishes to share a secret with a number of receiver parties in such a way that the secret is fully revealed only if a large enough portion of the receivers work together. However, if not enough receivers work together to reveal the secret, the secret remains completely unknown.

The classical scheme was independently proposed by Adi Shamir[1] and George Blakley[2] in 1979. In 1998, Mark Hillery, Vladimír Bužek, and André Berthiaume extended the theory to make use of quantum states for establishing a secure key that could be used to transmit the secret via classical data.[3] In the years following, more work was done to extend the theory to transmitting quantum information as the secret, rather than just using quantum states for establishing the cryptographic key.[4][5]

QSS has been proposed for being used in quantum money[6] as well as for joint checking accounts, quantum networking, and distributed quantum computing, among other applications.

Protocol

The simplest case: GHZ states

This example follows the original scheme laid out by Hillery et al. in 1998 which makes use of Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (GHZ) states. A similar scheme was developed shortly thereafter which used two-particle entangled states instead of three-particle states.[7] In both cases, the protocol is essentially an extension of quantum key distribution to two receivers instead of just one.

Following the typical language, let the sender be denoted as Alice and two receivers as Bob and Charlie. Alice's objective is to send each receiver a "share" of her secret key (really just a quantum state) in such a way that:

- Neither Bob's nor Charlie's share contains any information about Alice's original message, and therefore neither can extract the secret on their own.

- The secret can only be extracted if Bob and Charlie work together, in which case the secret is fully revealed.

- The presence of either an outside eavesdropper or a dishonest receiver (either Bob or Charlie) can be detected without the secret being revealed.

Alice initiates the protocol by sharing with each of Bob and Charlie one particle from a GHZ triplet in the (standard) Z-basis, holding onto the third particle herself:

where and are orthogonal modes in an arbitrary Hilbert space.

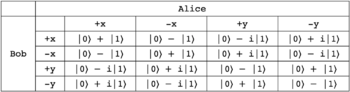

After each participant measures their particle in the X- or Y-basis (chosen at random), they share (via a classical, public channel) which basis they used to make the measurement, but not the result itself. Upon combining their measurement results, Bob and Charlie can deduce what Alice measured 50% of the time. Repeating this process many times, and using a small fraction to verify that no malicious actors are present, the three participants can establish a joint key for communicating securely. Consider the following for a clear example of how this will work.

Let us define the x and y eigenstates in the following, standard way:

- .

The GHZ state can then be rewritten as

- ,

where (a, b, c) denote the particles for (Alice, Bob, Charlie) and Alice's and Bob's states have been written in the X-basis. Using this form, it is evident that their exists a correlation between Alice's and Bob's measurements and Charlie's single-particle state:

if Alice and Bob have correlated results then Charlie has the state

and if Alice and Bob have anticorrelated results then Charlie has the state

.

It is clear from the table summarizing these correlations that by knowing the measurement bases of Alice and Bob, Charlie can use his own measurement result to deduce whether Alice and Bob had the same or opposite results. Note however that to make this deduction, Charlie must choose the correct measurement basis for measuring his own particle. Since he chooses between two noncommuting bases at random, only half of the time will he be able to extract useful information. The other half of the time the results must be discarded. Additionally, from the table one can see that Charlie has no way of determining who measured what, only if the results of Alice and Bob were correlated or anticorrelated. Thus the only way for Charlie to figure out Alice's measurement is by working together with Bob and sharing their results. In doing so, they can extract Alice's results for every measurement and use this information to create a cryptographic key that only they know.

((k,n)) threshold scheme

The simple case described above can be extended similarly to that done in CSS by Shamir and Blakley via a thresholding scheme. In the ((k,n)) threshold scheme (double parentheses denoting a quantum scheme), Alice splits her secret key (quantum state) into n shares such that any k≤n shares are required to extract the full information but k-1 or less shares cannot extract any information about Alice's key.

The number of users needed to extract the secret is bounded by n/2<k≤n. Consider for n≥2k, if a ((k,n)) threshold scheme is applied to two disjoint sets of k in n, then two independent copies of Alice's secret can be reconstructed. This of course would violate the no-cloning theorem and is why n must be less than 2k.

As long as a ((k,n)) threshold scheme exists, a ((k,n-1)) threshold scheme can be constructed by simply discarding one share. This method can be repeated until k=n.

The following outlines a simple ((2,3)) threshold scheme,[4] and more complicated schemes can be imagined by increasing the number of shares Alice splits her original state into:

Consider Alice beginning with the single qutrit state

and then mapping it to three qutrits

and sharing one qutrit with each of the 3 receivers. It is evident that a single share does not give any information about Alice's original state, since each share is in the maximally mixed state. However, two shares could be used to reconstruct Alice's original state. Assume the first two shares are given. Add the first share to the second (modulo three) and then add the new value of the second share to the first. The resulting state is

where the first qutrit is exactly Alice's original state. Via this method, the sender's original state can be reconstructed at one of the receivers' particles, but it is crucial that no measurements be made during this reconstruction process or any superposition within the quantum state will collapse.

Security

The security of QSS relies upon the no-cloning theorem to protect against possible eavesdroppers as well as dishonest users. This section adopts the two-particle entanglement protocol very briefly mentioned above.[7]

Eavesdropping

QSS promises security against eavesdropping in the exact same way as quantum key distribution. Consider an eavesdropper, Eve, who is assumed to be capable of perfectly discriminating and creating the quantum states used in the QSS protocol. Eve's objective is to intercept one of the receivers' (say Bob's) shares, measure it, then recreate the state and send it on to whomever the share was initially intended for. The issue with this method is that Eve needs to randomly choose a basis to measure in, and half of the time she will choose the wrong basis. When she chooses the correct basis, she will get the correct measurement result with certainty and can recreate the state she measured and send it off to Bob without her presence being detected. However, when she chooses the wrong basis, she will end up sending one of the two states from the incorrect basis. Bob will measure the state she sent him and half of the time this will be the correct detection, but only because the state from the wrong basis is an equal superposition of the two states in the correct basis. Thus, half of the time that Eve measures in the wrong basis and therefore sends the incorrect state, Bob will measure the wrong state. This intervention on Eve's part leads to causing an error in the protocol on an extra 25% of trials. Therefore, with enough measurements, it will be nearly impossible to miss the protocol errors occurring with a 75% probability instead of the 50% probability predicted by the theory, thus signaling that there is an eavesdropper within the communication channel.

More complex eavesdropping strategies can be performed using ancilla states, but the eavesdropper will still be detectable in a similar manner.

Dishonest Participant

Now, consider the case where one of the participants of the protocol (say Bob) is acting as a malicious user by trying to obtain the secret without the other participants being aware. Analyzing the possibilities, one learns that choosing the proper order in which Bob and Charlie release their measurement bases and results when testing for eavesdropping can promise the detection of any cheating that may be occurring. The proper order turns out to be:

- Receiver 1 releases measurement results.

- Receiver 2 releases measurement results.

- Receiver 2 releases measurement basis.

- Receiver 1 releases measurement basis.

This ordering prevents Receiver 2 from knowing which basis to share for tricking the other participants because Receiver 2 does not yet know what basis Receiver 1 is going to announce was used. Similarly, since Receiver 1 must release their results first, they cannot control if the measurements should be correlated or anticorrelated for the valid combination of bases used. In this way, acting dishonestly will introduce errors in the eavesdropper testing phase whether the dishonest participant is Receiver 1 or Receiver 2. Thus, the ordering of releasing the data must be carefully chosen so as to prevent any dishonest user from acquiring the secret without being noticed by the other participants.

Experimental Realization

This section follows from the first experimental demonstration of QSS in 2001 which was made possible via advances in techniques of quantum optics.[8]

The original idea for QSS using GHZ states was more challenging to implement because of the difficulties in producing three-particle correlations via either down-conversion processes with nonlinearities or three-photon positronium annihilation, both of which are rare events.[9] Instead, the original experiment was performed via the two-particle scheme using a standard spontaneous parametric down-conversion (SPDC) process with the third correlated photon being the pump photon.

The experimental setup works as follows:

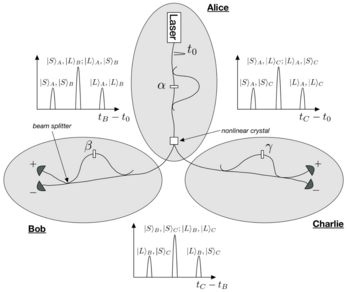

- Alice: A pulsed laser emitted at time enters an interferometer with unequal path lengths such that the pump is split into two distinct temporal pulses with equal amplitude. One arm of the interferometer contains a phase shifter to control the phase difference of the two arms, denoted The pump pulses are focused onto a nonlinear crystal where some of the pump photons are down-converted into photon pairs via SPDC. The SPDC pairs are then split, with one being sent to Bob and the other to Charlie.

- Bob and Charlie: Both receivers have identical interferometers to the one used by Alice such that the exact same time difference between the two arms is achieved and each has a phase shifter denoted as for Bob and for Charlie. The different possible trajectories of each interferometer lead to three distinct time differences between when Alice's pump pulse is emitted and when Bob's and Charlie's SPDC photons are detected ( and , respectively), as well as three time differences between the detections at each of Bob's and Charlie's detectors.

Using where X and Y are either 'S' for short path or 'L' for long path and i and j are one of 'A', 'B', or 'C' to label a participant's interferometer, this notation describes the arbitrary path taken for any combination of two participants. Notice that and where j is either 'B' or 'C' are indistinguishable processes as the time difference between the two processes are exactly the same. The same is true for and Describing these indistinguishable processes mathematically,

which can be thought of as a "pseudo-GHZ state" where the difference from a true GHZ state is that the three photons do not exist simultaneously. Nonetheless, the triple "coincidences" can be described by exactly the same probability function as for the true GHZ state,

implying that QSS will work just the same for this 2-particle source.

By setting the phases and to either 0 or in much the same way as two-photon Bell tests, it can be shown that this setup violates a Bell-type inequality for three particles,

- ,

where is the expectation value for a coincidence measurement with phase shifter settings . For this experiment, the Bell-type inequality was violated, with , suggesting that this setup exhibits quantum nonlocality.

This seminal experiment showed that the quantum correlations from this setup are indeed described by the probability function The simplicity of the SPDC source allowed for coincidences at much higher rates than traditional three-photon entanglement sources, making QSS more practical. This was the first experiment to prove the feasibility of a QSS protocol.

References

- ↑ Shamir, Adi (1 November 1979). "How to share a secret". Communications of the ACM 22 (11): 612–613. doi:10.1145/359168.359176. https://cs.jhu.edu/~sdoshi/crypto/papers/shamirturing.pdf.

- ↑ Blakley, G.R. (1979). "Safeguarding Cryptographic Keys". Managing Requirements Knowledge, International Workshop on (AFIPS) 48: 313–317. doi:10.1109/AFIPS.1979.98. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/32d2/1ccc21a807627fcb21ea829d1acdab23be12.pdf.

- ↑ Hillery, Mark; Bužek, Vladimír; Berthiaume, André (1998). "Quantum Secret Sharing". Physical Review A 59 (3): 1829–1834. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.59.1829. https://arxiv.org/pdf/quant-ph/9806063.pdf. Retrieved 2021-12-14.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cleve, Richard; Gottesman, Daniel; Lo, Hoi-Kwong (1999). "How to share a quantum secret". Physical Review Letters 83 (3): 648–651. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.648. https://arxiv.org/pdf/quant-ph/9901025.pdf. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Gottesman, Daniel (2000). "Theory of quantum secret sharing". Physical Review A 61 (4): 042311. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.61.042311. https://journals.aps.org/pra/pdf/10.1103/PhysRevA.61.042311. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Wiesner, Stephen (January 1983). "Conjugate coding". ACM SIGACT News 15 (1): 78–88. doi:10.1145/1008908.1008920. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Conjugate-coding-Wiesner/376b4787f0101d13125d81913d5cdc9a8037dee6. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Karlsson, Anders; Koashi, Masato; Imoto, Nobuyuki (1999). "Quantum entanglement for secret sharing and secret splitting". Physical Review A 59 (1): 162–168. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.59.162. https://journals.aps.org/pra/pdf/10.1103/PhysRevA.59.162. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Tittel, W.; Zbinden, H.; Gisin, N. (2001). "Experimental demonstration of quantum secret sharing". Physical Review A 63 (4): 042301. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.63.042301. https://journals.aps.org/pra/pdf/10.1103/PhysRevA.63.042301. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ↑ Żukowski, M.; Zeilinger, A.; Horne, M.A.; Weinfurter, H. (1998). "Quest for GHZ states". Acta Physics Polonica A 98 (1): 187–195. http://przyrbwn.icm.edu.pl/APP/PDF/93/a093z1p15.pdf. Retrieved 15 December 2021.