Relative homology

In algebraic topology, a branch of mathematics, the (singular) homology of a topological space relative to a subspace is a construction in singular homology, for pairs of spaces. The relative homology is useful and important in several ways. Intuitively, it helps determine what part of an absolute homology group comes from which subspace.

Definition

Given a subspace , one may form the short exact sequence

where denotes the singular chains on the space X. The boundary map on descendsa to and therefore induces a boundary map on the quotient. If we denote this quotient by , we then have a complex

By definition, the nth relative homology group of the pair of spaces is

One says that relative homology is given by the relative cycles, chains whose boundaries are chains on A, modulo the relative boundaries (chains that are homologous to a chain on A, i.e., chains that would be boundaries, modulo A again).[1]

Properties

The above short exact sequences specifying the relative chain groups give rise to a chain complex of short exact sequences. An application of the snake lemma then yields a long exact sequence

The connecting map takes a relative cycle, representing a homology class in , to its boundary (which is a cycle in A).[2]

It follows that , where is a point in X, is the n-th reduced homology group of X. In other words, for all . When , is the free module of one rank less than . The connected component containing becomes trivial in relative homology.

The excision theorem says that removing a sufficiently nice subset leaves the relative homology groups unchanged. If has a neighbourhood in that deformation retracts to , then using the long exact sequence of pairs and the excision theorem, one can show that is the same as the n-th reduced homology groups of the quotient space . This property is particularly important as it relates algebraic quotients and topological quotients.

Relative homology readily extends to the triple for .

One can define the Euler characteristic for a pair by

The exactness of the sequence implies that the Euler characteristic is additive, i.e., if , one has

Local homology

The -th local homology group of a space at a point , denoted

is defined to be the relative homology group . Informally, this is the "local" homology of close to .

Local homology of the cone CX at the origin

One easy example of local homology is calculating the local homology of the cone of a space at the origin of the cone. Recall that the cone is defined as the quotient space

where has the subspace topology. Then, the origin is the equivalence class of points . Using the intuition that the local homology group of at captures the homology of "near" the origin, we should expect this is the homology of since has a homotopy retract to . Computing the local homology can then be done using the long exact sequence in homology

Because the cone of a space is contractible, the middle homology groups are all zero, giving the isomorphism

since deformation retracts to .

In algebraic geometry

Note the previous construction can be proven in algebraic geometry using the affine cone of a projective variety using Local cohomology.

Local homology of a point on a smooth manifold

Another computation for local homology can be computed on a point of a manifold . Then, let be a compact neighborhood of isomorphic to a closed disk and let . Using the excision theorem there is an isomorphism of relative homology groups

hence the local homology of a point reduces to the local homology of a point in a closed ball . Because of the homotopy equivalence

and the fact

the only non-trivial part of the long exact sequence of the pair is

hence the only non-zero local homology group is .

Functoriality

Just as in absolute homology, continuous maps between spaces induce homomorphisms between relative homology groups. In fact, this map is exactly the induced map on homology groups, but it descends to the quotient.

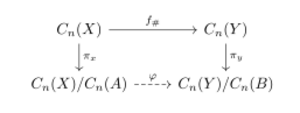

Let and be pairs of spaces such that and , and let be a continuous map. Then there is an induced map on the (absolute) chain groups. If , then . Let

be the natural projections which take elements to their equivalence classes in the quotient groups. Then the map is a group homomorphism. Since , this map descends to the quotient, inducing a well-defined map such that the following diagram commutes:[3]

Chain maps induce homomorphisms between homology groups, so induces a map on the relative homology groups.[2]

Examples

One important use of relative homology is the computation of the homology groups of quotient spaces . In the case that is a subspace of fulfilling the mild regularity condition that there exists a neighborhood of that has as a deformation retract, then the group is isomorphic to . We can immediately use this fact to compute the homology of a sphere. We can realize as the quotient of an n-disk by its boundary, i.e. . Applying the exact sequence of relative homology gives the following:

Because the disk is contractible, we know its reduced homology groups vanish in all dimensions, so the above sequence collapses to the short exact sequence:

Therefore, we get isomorphisms . We can now proceed by induction to show that . Now because is the deformation retract of a suitable neighborhood of itself in , we get that .

Another insightful geometric example is given by the relative homology of where . Then we can use the long exact sequence

Using exactness of the sequence we can see that contains a loop counterclockwise around the origin. Since the cokernel of fits into the exact sequence

it must be isomorphic to . One generator for the cokernel is the -chain since its boundary map is

See also

Notes

^ i.e., the boundary maps to

References

- "Relative homology groups". http://planetmath.org/?op=getobj&from=objects&id={{{id}}}.

- Joseph J. Rotman, An Introduction to Algebraic Topology, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-96678-1

- Specific

- ↑ Hatcher, Allen (2002). Algebraic topology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521795401. OCLC 45420394.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hatcher, Allen (2002). Algebraic topology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 9780521795401. OCLC 45420394.

- ↑ Dummit, David S.; Foote, Richard M. (2004). Abstract algebra (3 ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 9780471452348. OCLC 248917264.

|