Religion:Al-Uzza

| Al-Uzza | |

|---|---|

Goddess of might, protection, and love | |

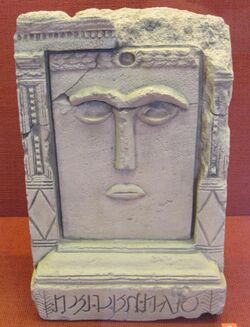

2nd century AD relief from Hatra depicting the goddess al-Lat flanked by two female figures, possibly goddesses al-Uzza and Manat | |

| Major cult center | Petra |

| Symbol | Three trees |

| Region | Arabia (Arabian Peninsula) |

| Personal information | |

| Siblings | Al-Lat, Manāt |

| Greek equivalent | Aphrodite |

| Roman equivalent | Venus |

| Part of the myth series on |

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Pre-Islamic Arabian deities |

| Arabian deities of other Semitic origins |

|

Al-ʻUzzā (Arabic: العزى al-ʻUzzā [al ʕuzzaː] or Old Arabic [al ʕuzzeː]) was one of the three chief goddesses of Arabian religion in pre-Islamic times and she was worshiped by the pre-Islamic Arabs along with al-Lāt and Manāt. A stone cube at Nakhla (near Mecca) was held sacred as part of her cult. She is mentioned in Qur'an 53:19 as being one of the goddesses who people worshiped.

Al-ʻUzzā, like Hubal, was called upon for protection by the pre-Islamic Quraysh. "In 624 at the 'battle called Uhud', the war cry of the Qurayshites was, "O people of Uzzā, people of Hubal!".[1] Al-‘Uzzá also later appears in Ibn Ishaq's account of the alleged Satanic Verses.[2]

The temple dedicated to al-ʻUzzā and the statue was destroyed by Khalid ibn al Walid in Nakhla in 630 AD.[3][4]

Cult of al-‘Uzzá

According to the Book of Idols (Kitāb al-Aṣnām) by Hishām ibn al-Kalbī[5]

Over her [an Arab] built a house called Buss in which the people used to receive oracular communications. The Arabs as well as the Quraysh used to name their children "‘Abdu l-ʻUzzā". Furthermore, al-ʻUzzā was the greatest idol among the Quraysh. They used to journey to her, offer gifts unto her, and seek her favours through sacrifice.[6]

- The Quraysh used to circumambulate the Ka‘bah and say,

- By al-Lāt and al-ʻUzzā,

- And al-Manāt, the third idol besides.

- Verily they are al-gharānīq

- Whose intercession is to be sought.

This last phrase is said to be the source of the so-called Satanic Verses; the Arabic term is translated as "most exalted females" by Faris in the Book of Idols, but he annotates this much-argued term in a footnote as "lit. Numidian cranes."

Each of the three goddesses had a separate shrine near Mecca. The most prominent Arabian shrine of al-ʻUzzā was at a place called Nakhlah near Qudayd, east of Mecca toward aṭ-Ṭā’if; three trees were sacred to her there (according to a narration through al-'Anazi Abū-‘Alī in the Kitāb al-Aṣnām.)

She was the Lady ‘Uzzayan to whom a South Arabian offered a golden image on behalf of his sick daughter, Amat-‘Uzzayan ("the Maid of ‘Uzzayan")

‘Abdu l-‘Uzzá ["Slave of the Mightiest One"] was a favourite proper name before the advent of Islam.[7] The name al-‘Uzzá appears as an emblem of beauty in late pagan Arabic poetry quoted by Ibn al-Kalbī, and oaths were sworn by her.

Susan Krone suggests that the identities of al-‘Uzzá and al-Lāt were fused in central Arabia uniquely.[8]

On the authority of ‘Abdu l-Lāh ibn ‘Abbās, at-Tabari derived al-ʻUzzā from al-‘Azīz "the Mighty", one of the 99 "beautiful names of Allah" in his commentary on Qur'an 7:180.[citation needed]

Destruction of temple

Shortly after the Conquest of Mecca, Muhammad began efforts to eliminate the last cult images reminiscent of pre-Islamic practices.

He sent Khalid ibn Al-Walid during Ramadan 630 AD (8 AH) to a place called Nakhlah, where the goddess al-ʻUzzā was worshipped by the tribes of Quraish and Kinanah. The shrine's custodians were from Banu Shaiban. Al-ʻUzzā was considered the most important goddess in the region.

Arab Muslim historian Ibn al-Kalbī (c. 737–819 CE) tells how Muhammad ordered Khālid ibn al-Walīd to kill the pre-Islamic Arabian goddess al-ʿUzzā, who was supposed to inhabit one of three trees:

- Khalid destroyed the first one, returned to Muhammad to report. Muhammad replied, asking whether something eventful happened, which Khalid denied. The same thing happened after cutting down the second tree. When Khalid was about to destroy the last tree, a woman with wild hair appeared, who is called "al Uzza" by al-Sulami the custodian of al-Uzza, and ordered [ ] to kill Khalid. Khalid struck the woman down with his sword, and chopped her head off at which she fell down in a pile of ashes. Khalid went on to kill Sulami and cut the last tree. When he returned to Muhammad, Muhammad is supposed to have said that the woman was al-Uzza, and she shall never be worshiped again.[9]

Influence in other religions

Uzza the garden

According to Easton's Bible Dictionary, Uzza was a garden in which Manasseh and Amon were buried (2 Kings 21:18, 26). It was probably near the king's palace in Jerusalem, or may have formed part of the palace grounds. Manasseh may have acquired it from someone of this name. Another view is that these kings were culpable of idolatry and drew the attention of Ezekiel.[10]

As an angel

In Judaic and Christian lore, a deity name similar to Semyazza currently is claimed as a cognate of Uzza. Uzza also has been used as an alternative name for the angel Metatron in the Sefer ha-heshek. More commonly he is referred to as either the seraph Samyaza or as one of the three guardian angels of Egypt (Rahab, Mastema, and Duma) who harried the Jews during the Exodus.[11]

Under the name Semyaza, he is the seraph in legend tempted by Ishtahar into revealing the explicit name of God, and was thus burned alive and hung head down between heaven and earth as the constellation Orion.[12] In the 3rd Book of Enoch and in the Zohar he is one of the fallen angels punished for cohabiting with human women and fathering the anakim.[13]

ʻUzzā is also identified with Abezi Thibod ("father devoid of counsel") who in early Jewish lore is also used as another name for Samael and Mastema, referring to a powerful spirit who opposed Moses, and shared princedom of Egypt with Rahab, and who eventually drown in the Red Sea.[14]

See also

- Manāt

- Al-Lat

- Ushas

References

- ↑ Tawil (1993).

- ↑ Ibn Ishaq Sirat Rasul Allah, pp. 165–167.

- ↑ S.R. Al-Mubarakpuri. The sealed nectar. p. 256. https://books.google.com/books?id=-ppPqzawIrIC&pg=PA256. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

- ↑ "He sent Khalid bin Al-Waleed in Ramadan 8 A.H", Witness-Pioneer.com

- ↑ Ibn al-Kalbi, trans. Faris (1952), pp. 16–23.

- ↑ Jawad Ali, Al-Mufassal Fi Tarikh al-Arab Qabl al-Islam (Beirut), 6:238-9

- ↑ Hitti (1937), pp. 96–101.

- ↑ Krone, Susan (1992). Die altarabische Gottheit al-Lat Cited in Arabic Theology, Arabic Philosophy: From the Many to the One. Berlin: Speyer & Peters GmbH. p. 96. ISBN 9783631450925. https://books.google.com/books?id=g_IJCIT8CdAC&pg=PA96.

- ↑ Elias, J.J. (2014). Key Themes for the Study of Islam. London, UK : Oneworld Publications.

- ↑ Provan, Iain W. (1988). Hezekiah and the Books of Kings: A Contribution to the Debate about the Composition of the Deuteronomistic History. (Volume 172 of Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft) Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 136n13. ISBN 9783110849424. Retrieved 6 June 2016. Google Books

- ↑ Davidson (1967), pp. xiii, xxiv.

- ↑ Davidson (1967), p. 301.

- ↑ Davidson (1967), pp. 18, 65.

- ↑ Davidson (1967), p. 4.

Bibliography

- Ambros, Arne A. (2004). A Concise Dictionary of Koranic Arabic. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89500-400-1.

- Berkey, Jonathan Porter (2003). The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600-1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58813-3. https://archive.org/details/formationofislam0000berk.

- Burton, John (1977). The Collection of the Qur'an (the collection and composition of the Qu'ran in the lifetime of Muhammad). Cambridge University Press.

- Davidson, Gustav (1967). A Dictionary of Angels: Including the Fallen Angels. Scrollhouse. ISBN 978-0-02-907052-9.

- Finegan, Jack (1952). The Archeology of World Religions. Princeton University Press. pp. 482–485, 492. https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.44705.

- Peters, Francis E. (1994b), Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1875-8, https://archive.org/details/muhammadorigins00pete

- Hitti, Philip K. (1937). History of the Arabs.

- Ibn al-Kalbī, Hisham (1952). The Book of Idols, Being a Translation from the Arabic of the Kitāb al-Asnām. Translation and commentary by Nabih Amin Faris. Princeton University Press.

- Peters, F. E. (1994). The Hajj: The Muslim Pilgrimage to Mecca and the Holy Places. Princeton University Press. https://archive.org/details/hajjmuslimpilgri0000pete.

- al-Tawil, Hashim (1993). Early Arab Icons: Literary and Archaeological Evidence for the Cult of Religious Images in Pre-Islamic Arabia (PhD thesis). University of Iowa. Archived from the original on 2005-01-20.

External links

- "Those Are The High Flying Claims": A Muslim site on Satanic Verses story

- Nabataean pantheon including al-ʻUzzā

- Quotes concerning al-‘Uzzá from Hammond and Hitti