Religion:Baháʼí Faith and science

A fundamental principle of the Baháʼí Faith is the stated harmony of religion and science.[1] Whilst Baháʼí scripture asserts that true science and true religion can never be in conflict, critics argue that statements by the founders clearly contradict current scientific understanding.[2][3] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, the son of the founder of the religion, stated that "when a religion is opposed to science it becomes mere superstition".[4] He also said that true religion must conform to the conclusions of science.[5][6]

This latter aspect of the principle seems to suggest that the religion must always accept current scientific knowledge as authoritative, but some Baháʼí scholars have suggested that this is not always the case.[7] On some issues, the Baháʼí Faith subordinates the conclusions of current scientific thought to its own teachings, which the religion takes as fundamentally true.[8] This is because, in the Baháʼí understanding the present scientific view is not always correct, neither is truth said to be only limited to what science can explain.[6] Instead, in the Baháʼí view, knowledge must be obtained through the interaction of the insights obtained from revelation from God and through scientific investigation.[9]

Overall Baháʼí attitude

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, the son of the founder of the religion, asserted that science and religion cannot be opposed because they are aspects of the same truth; he also affirmed that reasoning powers are required to understand the truths of religion. Shoghi Effendi, the head of the Baháʼí Faith in the first half of the 20th century, described science and religion as "the two most potent forces in human life".[10]

The teachings state that whenever conflict arises between religion and science it is due to human error; either through misinterpretation of religious scriptures or the lack of a more complete understanding of science. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá explained that religious teachings which are at variance with science should not be accepted; he explained that religion has to be reasonable since God endowed humankind with reason so that they can discover truth.[5] Science and religion, in the Baháʼí writings, are compared to the two wings of a bird upon which a person's intelligence can increase, and upon which a person's soul can progress. Furthermore, the Baháʼí writings state that science without religion would lead to a person becoming totally materialistic, and religion without science would lead to a person falling into superstitious practices. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in one of his public talks said:

If religion were contrary to logical reason then it would cease to be a religion and be merely a tradition. Religion and science are the two wings upon which man's intelligence can soar into the heights, with which the human soul can progress. It is not possible to fly with one wing alone! Should a man try to fly with the wing of religion alone he would quickly fall into the quagmire of superstition, whilst on the other hand, with the wing of science alone he would also make no progress, but fall into the despairing slough of materialism. All religions of the present day have fallen into superstitious practices, out of harmony alike with the true principles of the teaching they represent and with the scientific discoveries of the time.[11]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá is quoted as saying the following:

Mathematicians, astronomers, chemical scientists continually disprove and reject the conclusions of the ancients; nothing is fixed, nothing final; everything is continually changing because human reason is progressing along new roads of investigation and arriving at new conclusions every day. In the future much that is announced and accepted as true now will be rejected and disproved. And so it will continue ad infinitum.[12]

Scientific claims by the founders

Creation

Baháʼu'lláh taught that the differing views on the subject of the creation of the universe are relative to the observer. He writes, regarding the age of the earth, that "Wert thou to assert that it hath ever existed and shall continue to exist, it would be true; or wert thou to affirm the same concept as is mentioned in the sacred Scriptures, no doubt would there be about it".[13] Abdu'l Baha emphasised the view that the universe has "neither beginning nor ending",[14] and that the component elements of the material world have always existed and will continue to exist.[15] However, he elucidated the apparent contradiction between the origination and eternality of the universe, writing that “existence and nonexistence are both relative. If it be said that such a thing came into existence from nonexistence, this does not refer to absolute nonexistence, but means that its former condition in relation to its actual condition was nothingness.”.[16] Moojan Momen has further explored other examples of cognitive relativism in the Baha'i writings.[17] In the Tablet of Wisdom ("Lawh-i-Hikmat", written 1873–1874). Baháʼu'lláh states: "That which hath been in existence had existed before, but not in the form thou seest today. The world of existence came into being through the heat generated from the interaction between the active force and that which is its recipient. These two are the same, yet they are different." The terminology used here echoes Hindu philosophy and refers to ancient Greek and Islamic philosophy.[18][19][20] Jean-Marc Lepain, Robin Mihrshahi, Dale E. Lehman and Julio Savi suggest a possible relation of this statement with the Big Bang theory.[21][22][23][24]

Baháʼís believe that the story of creation in Genesis is a rudimentary account that conveys the broad essential spiritual truths of existence without a level of detail and accuracy that would have been unnecessary and incomprehensible at the time.[15] Likewise, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá said that literal story of Adam and Eve cannot be accepted, affirmed, or imagined, and that it "must be thought of simply as a symbol".[25] And rather than accepting the idea of a Young Earth, Baháʼí theology accepts that the Earth is ancient.[26]

Evolution

In regards to evolution and the origin of man, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá gave extensive comments on the subject when he addressed western audiences in the beginning of the 20th century. Transcripts of these talks can be found in Some Answered Questions, Paris Talks and the Promulgation of Universal Peace. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá describes the human species as evolving from a primitive form to modern man, but that the capacity to form human intelligence was always in existence.[citation needed]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's comments seem to differ from the standard evolutionary picture of human development, where Homo sapiens as one species along with the great apes evolved from a common ancestor living in Africa millions of years ago.

While ʻAbdu'l-Bahá states that man progressed through many stages before reaching this present form, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá states that humans are a distinct species, and not an animal, and that in every stage of evolution through which humans progressed, they were potentially humans.

But at all times, even when the embryo resembled a worm, it was human in potentiality and character, not animal. The forms assumed by the human embryo in its successive changes do not prove that it is animal in its essential character. Throughout this progression there has been transference of type, a conservation of species or kind. Realizing this we may acknowledge the fact that at one time man was an inmate of the sea, at another period an invertebrate, then a vertebrate and finally a human being standing erect. Though we admit these changes, we cannot say man is an animal. In each one of these stages are signs and evidences of his human existence and destination.[27]

Mehanian and Friberg wrote a 2003 article describing their belief that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's statements can be entirely reconciled with modern science. Mehanian and Friberg state that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's departures from the conventional interpretation of evolution are likely due "to disagreements with the metaphysical, philosophical, and ideological aspects of those interpretations, not with scientific findings."[6] Gary Matthews argues that it was to this end that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá suggested that a missing link between human and apes would not be found.[28]

There are some differences between ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's statements and current scientific thought. The Baháʼí perspective that religion must be in accordance with science seems to suggest that religion must accept current scientific knowledge as authoritative; but, according to Mehanian and Friberg, this is not necessarily always the case as in their view the present scientific point of view is not always correct, nor truth only limited to what science can explain.[6]

Oskooi chose the subject of evolution and Baháʼí belief for his 2009 thesis, and in doing so reviewed other Baháʼí authors' works on the subject. He concluded that, "The problem of disharmony between scripture and science is rooted in an unwarranted misattribution of scriptural inerrancy."[29] In other words, he believes that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá made statements about biology that were later proved wrong, and that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's infallibility should not be applied to scientific matters.

Several authors have written on the subject of evolution and Baháʼí belief.

- Craig Loehle (1990), On Human Origins: A Baháʼí Perspective

- Eberhard von Kitzing (1997), Is the Baháʼí view of evolution compatible with modern science?

- Courosh Mehanian and Stephan Friberg (2003), Religion and Evolution Reconciled: ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Comments on Evolution

- Bahman Nadimi, Do the Bahaʼi Writings on evolution allow for mutation of species within kingdoms but not across kingdoms?

- Keven Brown (2001), Evolution and Baháʼí Belief: ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Response to Nineteenth-Century Darwinism

- Fariborz Alan Davoodi, MD, Human Evolution: Directed?

- Salman Oskooi (2009), When Science and Religion Merge: A Modern Case Study

Existence of ether

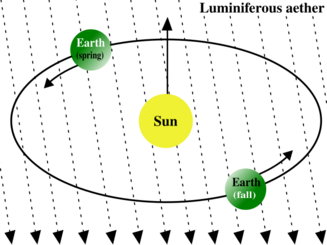

Aether, or ether, was a substance postulated in the late 19th century to be the medium for the propagation of light. The Michelson–Morley experiment of 1887 made an effort to find the aether, but its failure to detect it led Einstein to devise his Special theory of Relativity. Further developments in modern physics, including general relativity, quantum field theory, and string theory all incorporate the non-existence of the aether, and today the concept is considered obsolete scientific theory.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's use of the aether concept in one of his talks - his audience including scientists of the time - has been the source of some controversy. The chapter in ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Some Answered Questions which mentions aether differentiates between things that are "perceptible to the senses" and those which are "realities of the intellect" and not perceptible to the senses.[30] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá includes "ethereal matter" (also translated as "etheric matter"), heat, light and electricity among other things, in the second group of things which are not perceptible to the senses, and are concepts which are arrived at intellectually to explain certain phenomena.[30] The Universal House of Justice referring to ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's use of the word state that, "in due course, when scientists failed to confirm the physical existence of the 'ether' by delicate experiments, they constructed other intellectual concepts to explain the same phenomena" which is consistent with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's categorization of aether.[30]

Robin Mishrahi wrote a 2002 paper in the Australian Baháʼí Studies Journal, arguing that Baháʼu'lláh and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá were using already existing concepts and terms to accurately explain what they had in mind, "in such a way that they would neither offend Their addressees who believed in certain (erroneous) contemporary scientific concepts, nor make use of a terminology that had not yet been developed by contemporary scientists."[22]

Nuclear power

Baháʼu'lláh wrote:

Strange and astonishing things exist in the earth but they are hidden from the minds and the understanding of men. These things are capable of changing the whole atmosphere of the earth and their contamination would prove lethal."[31]

Baháʼís later pointed to this as a statement about the discovery of nuclear energy and the use of nuclear weapons.[32]

Turning copper into gold

Bahá'u'lláh in the early 1860s, claimed that Copper can be turned into Gold and that its secret lies hidden in his knowledge. He also claimed that changing of one element into other (transmutation of elements) would become reality.[33]

Some Bahá'is take this as metaphorical,[34] while others claim that Baháʼu'lláh was narrating the beliefs of others.[3]

Transmission of cancer

‘Abdu’l-Bahá claimed that “bodily diseases like consumption and cancer are contagious” and that “safe and healthy persons” must guard against it.[35][36]

See also

- Creationism

- Creation–evolution controversy

- Baháʼí cosmology

- Baháʼí prophecies

- Dialectics

- Dialectical naturalism

- Islam and science

- Religion and science

Notes

- ↑ Research Department of the Universal House of Justice (August 2020). "Social Action". Bahá’í Reference Library. Coherence Between the Material and Spiritual Dimensions of Existence. https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/compilations/social-action/.

- ↑ Various (1975-12-26). Letter written on behalf of the Universal House of Justice. Research Department of the Universal House of Justice, Baháʼí World Centre (published December 1995). http://www.reference.bahai.org/en/t/c/SCH/sch-49.html#gr1. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Basiti; Moradi; Akhoondali (2014). Twelve Principles: A Comprehensive Investigation on the Baha'i Teachings (1st ed.). Tehran: Bahar Afshan Publications. p. 176.

- ↑ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1912, pp. 141–146

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Effendi 1912

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Mehanian & Friberg 2003

- ↑ "It also requires us not to limit science to any particular school of thought or methodological approach postulated in the course of its development." in Universal House of Justice (1997-08-13). "19 May 1995 letter, written on behalf of the Universal House of Justice to an individual believer (published in Memorandum on Quotations on Science and Religion". http://bahai-library.com/compilation_science_technology.html#14.

- ↑ Effendi 1946

- ↑ Universal House of Justice (1997-08-13). "19 May 1995 letter, written on behalf of the Universal House of Justice to an individual believer (published in Memorandum on Quotations on Science and Religion". http://bahai-library.com/compilation_science_technology.html#14.

- ↑ Effendi 1938

- ↑ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1912, p. 143

- ↑ Effendi 1912, p. 21

- ↑ Brown, Vahid. The beginning that hath no beginning:Bahá'í Cosmogony in Lights of Irfan, Book 3, 2002, pp. 21.

- ↑ Effendi 1912, p. 220

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Esslemont 1980, pp. 204–205

- ↑ Brown, Vahid. The beginning that hath no beginning:Bahá'í Cosmogony in Lights of Irfan, Book 3, 2002, pp. 23.

- ↑ Momen, Moojan. Studies in Honor of the Late Hasan M. Balyuzi: Relativism: A Basis For Bahá'í Metaphysics. p. 206. https://bahai-library.com/momen_relativism_bahai_metaphysicslocation=.

- ↑ Taherzadeh, A. (1987). The Revelation of Baháʼu'lláh, Volume 4: Mazra'ih & Bahji 1877-92. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. pp. 42. ISBN 0-85398-270-8. http://www.peyman.info/cl/Baha'i/Others/ROB/V4/Cover.html.

- ↑ Brown, Keven. A Bahá'í Perspective on the Origin of Matter. Journal of Bahá'í Studies. Vol. 2 no. 3, 1990, pp. 15-42.

- ↑ Brown, Vahid. The beginning that hath no beginning:Bahá'í Cosmogony in Lights of Irfan, Book 3, 2002, pp. 21-40.

- ↑ Lepain, Jean-Marc (2015) [2002]. The Archeology of the Kingdom of God.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Mihrshahi 2002.

- ↑ Lehman, Dale E. (2005). Cosmology and the Baháʼí Writings .

- ↑ Julio, Savi (1989). The Eternal Quest for God: An Introduction to the Divine Philosophy of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. pp. 134. ISBN 0-85398-295-3. http://bahai-library.com/pdf/s/savi_eternal_quest.pdf.

- ↑ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1912, p. 140

- ↑ Brown, Keven; Von Kitzing, Eberhard, eds (2001). Evolution and Baháʼí belief: ʻAbduʾl-Bahá's response to nineteenth-century Darwinism; Volume 12 of Studies in the Bábí and Baháʼí religions. Kalimat Press. pp. 6, 17, 117, etc.. ISBN 978-1-890688-08-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=egDAfpkONRsC.

- ↑ Effendi 1912, p. 358

- ↑ Matthews, Gary L. (2005). The Challenge of Baha'u'llah. US Baha'i Publishing Trust. pp. 90–5. ISBN 978-1-931847-16-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=EGbZMLCmE1IC&pg=PA90.

- ↑ "When Science and Religion Merge". Bahai-library.com. http://bahai-library.com/oskooi_disharmony_science_religion.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Letter to an individual by the Universal House of Justice

- ↑ Baháʼu'lláh 1994, p. 69

- ↑ Smith, Peter (2000). "nuclear power". A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 260–261. ISBN 1-85168-184-1. https://archive.org/details/conciseencyclope0000smit/page/260.

- ↑ Gary L. Matthews (1999). The challenge of Bahá'u'lláh. Internet Archive. George Ronald. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-85398-360-6. http://archive.org/details/challengeofbahau00matt.

- ↑ Buck, Christopher (2016-08-13). "Inner Gold: Alchemy of Attributes" (in en-US). https://bahaiteachings.org/inner-gold-alchemy-attributes/.

- ↑ "Lights of Guidance" (in en-US). https://bahai-library.com/hornby_lights_guidance.html&chapter=2#n603.

- ↑ Matthews, Gary L. (2005) (in en). The Challenge of Baha'u'lluah. Baha'i Publishing Trust. pp. 88. ISBN 978-1-931847-16-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=EGbZMLCmE1IC&pg=PA88.

References

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1908). Some Answered Questions. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust (published 1990).

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (2014). Some Answered Questions (Newly revised. ed.). Haifa, Israel: Baháʼí World Centre. ISBN 978-0-87743-374-3.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1912). Paris Talks. London: Baháʼí Distribution Service (published 1995). ISBN 1-870989-57-0. http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/ab/PT/.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1978). Gail, Marzieh. ed. Selections From the Writings of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-85398-081-0. http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/ab/SAB/.

- Baháʼu'lláh (1990). Effendi, Shoghi. ed. Gleanings from the Writings of Baháʼu'lláh. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-187-6. https://archive.org/details/gleaningsfromwri0000baha_w8j0.

- Baháʼu'lláh (1994). Tablets of Baháʼu'lláh Revealed After the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-174-4. http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/b/TB/.

- Effendi, Abbas (1912). The Promulgation of Universal Peace. US Baháʼí Publishing Trust (published 1987). ISBN 0-87743-172-8. http://www.reference.bahai.org/en/t/ab/PUP/pup-117.html#gr9.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1946). Arohanui: Letters from Shoghi Effendi to New Zealand. Suva, Fiji Islands: Baháʼí Publishing Trust (published 1982). http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/se/ARO/aro-75.html#gr2.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1938). The World Order of Baháʼu'lláh. Wilmette, Illinois: Baháʼí Publishing Trust (published 1991). ISBN 0-87743-231-7. http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/se/WOB/index.html.

- Esslemont, J.E. (1980). Baháʼu'lláh and the New Era (5th ed.). Wilmette, Illinois: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-160-4. http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/je/BNE/.

- Hornby, Helen, ed (1994). "On behalf of Shoghi Effendi to an individual believer, 9 February 1937". Lights of Guidance: A Baháʼí Reference File. New Delhi, India: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 81-85091-46-3. http://bahai-library.com/hornby_lights_guidance&chapter=2#n1221.

- Mihrshahi, Robin (2002). "Ether, Quantum Physics and the Baháʼí Writings". Australian Baháʼí Studies Journal 4: 3–20. http://bahai-library.com/mihrshahi_ether_quantum_physics.

- Mehanian, Courosh; Friberg, Stephen R. (2003). "Religion and Evolution Reconciled: ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Comments on Evolution". The Journal of Baháʼí studies 13 (1–4): pp. 55–93. http://www.bahai-studies.ca/journal/files/jbs/13.14%20Mehanian%20&%20Friberg.pdf.

- Taherzadeh, A. (1987). The Revelation of Baháʼu'lláh, Volume 4: Mazra'ih & Bahji 1877-92. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-270-8. http://www.peyman.info/cl/Baha'i/Others/ROB/V4/Cover.html.

External links

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá on Science and Religion

- Warwick Leaflet on Science and Religion

- A letter from the Universal House of Justice (13 August 1997) and a compilation of "Selected Extracts on Science and Technology"