Religion:Church of Santa Maria la Blanca (Seville)

[ ⚑ ] 37°23′11″N 5°59′14″W / 37.38639°N 5.98722°W

| Church of San Maria la Blanca | |

|---|---|

Assets of cultural interest | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic |

| District | Seville |

| Province | Seville |

| Leadership | Father Miguel Ángel Núñez Aguilera |

| Location | |

| Location | Andalucia Spain |

| Geographic coordinates | [ ⚑ ] 37°23′11″N 5°59′14″W / 37.38639°N 5.98722°W |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Borrominesque |

| Funded by | 17th century |

| Expression error: Unexpected < operator. | |

| Inscriptions | Cultural monument on July 25, 1995, November 15, 1995, and June 12, 1995 |

The Church of Santa María la Blanca (Spanish: Iglesia de Santa Maria la Blanca) is located in the San Bartolomé neighborhood of the district of Casco Antiguo in Seville (Andalusia, Spain). It was built in the 17th century. It is the headquarters of the Brotherhood of the Rosary of Our Lady of the Snows[1] (Hermandad del Rosario de Nuestra Señora de las Nieves).

History

In this place, there was a building belonging to the time of the Visigothic Hispania. The south portal of the temple, on Archeros Street, has two columns with Visigothic capitals.[2]

After the Reconquest of Seville in 1248, Ferdinand III ceded to the Archdiocese of Seville all the mosques in the city, except for three in the Jewish quarter, which were ceded to the Jews to be their synagogues.[2] This was confirmed by Alfonso X in 1252. This place was one of those synagogues, built in the 13th century,[3][4] of which no remains are preserved.[2]

In 1391, after the anti-Jewish revolt of that year, it was transformed into a Christian church. It was of Gothic-Mudejar style.[5] In this adaptation to Catholic worship, a new façade was built, of which the façade and the first section of the belfry are preserved.[2]

In 1642 the baptismal chapel was built. Between 1642 and 1646 Diego Gómez built the chapel of the sacramental brotherhood on top of a house annexed to the church that functioned as a tavern.[6][2] The main chapel was built in 1660. Between 1662 and 1665 the nave of the church and the vaults were rebuilt.[7]

In July 1662, Justino de Neve contracted Juan González to build the church vaults. The project consisted of a central vault with lunettes and a dome on pendentives. He also changed the old stone columns for new ones, made by the stonemason Gabriel de Mena in jasper from the Antequera quarries.[6]

The plasterwork of the central vault and the dome were made by Borja and Pedro Roldán.[8]

The reform of the temple in the 17th century was financed by a collection made by the visitor of the archbishopric, Justino de Neve, who was a member of the sacramental brotherhood. The parish priest was Domingo Velázquez Soriano.[2]

In 1665, on the occasion of the inauguration of the renovated church, Miguel Mañara organized a procession that also celebrated the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary.[9][10]

Between 2010 and 2015 the church underwent a restoration process.[11]

Description

Exterior

The church has two small facades on the exterior.

The main façade, facing Santa María la Blanca street, develops in the form of a tower façade. It consists, in the lower part, of a pointed flared arch. The thread of the same is decorated with diamond points carved in stone. In the superior part, three bodies are distinguished: The first one presents two openings of average point, without any decoration; in the following one the belfry is located, with two openings of average point framed by pilasters and finished off by a broken pediment; finally, a small belfry is located composed by an opening of average point framed by pilasters and crowned by ceramic finishes and a cross-velvet. To the right of the main door, there is a tile flanked by lanterns in which the image of the Virgin of the Snows is reproduced. It was painted by Antonio Morilla in 1957.[12]

On the wall of the epistle, towards Archeros Street, there is a doorway, currently unused, which would have been the original entrance to the church.[2] It has a segmental arch with a blind tympanum between two columns with Corinthian capitals. These capitals, because of their stylistic characteristics, may correspond to the late Roman or Visigothic period.

Interior

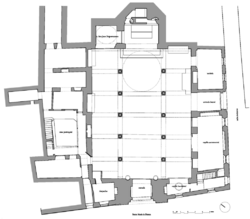

The church was decorated in 1657 by the brothers Pedro and Miguel de Borja.[3] The temple has a rectangular floor plan, with an extension of the chancel and two bodies, also rectangular, attached to the wall of the Epistle. The interior has three naves divided into six sections by 10 Tuscan columns of red marble, over them we find semicircular arches that support barrel vaults with false lunettes in the central nave and groin vaults in the lateral ones. Over the last two bays of the central nave, in front of the presbytery, there is a dome on pendentives, illuminated by two lateral oculi. The space of the presbytery is covered by a barrel vault with lunettes.

The entire surface of the vaults, dome, and intrados of the arches are filled with a profuse and volumetric decoration of plasterwork with geometric, vegetal, and figurative motifs, which, together with the mural paintings, which follow the sequence of the plasterwork, give movement to an orthogonal floor plan without dynamism.

At the foot of the Epistle nave is the baptismal chapel, where the stairway leading to the tower and the choir is located. Next to it is the sacramental chapel, with a rectangular floor plan and, following along the same nave, the sacristy.

The sacramental chapel is presided over by an altarpiece from 1722.[13] It is occupied by a calvary of heterogeneous composition with images that belonged to the inactive Brotherhood of the Lavatory. The Christ of the Mandate was made by Diego García de Santa Ana in wood paste in 1559.[14] The Virgin of the Pópulo is a dressed sorrow that has been in this temple since 1610. It was restored in 2021[15] and has a silver crown chiseled by Blas Amat in the 18th century.[16] The San Juan has been linked after its restoration in 2017 with the work of Cristóbal Ramos.[17]

It had several paintings by Murillo, of which only The Supper (La Cena), painted in 1650, is preserved in the church.[3] Under the half-orange of the ante-presbytery were The Dream of the Patrician and The Patrician John and his wife before Pope Liberius, two canvases that narrate the origin of the devotion to the Virgin of the Snows. They were plundered by Marshal Soult during the French invasion and, returned to Spain, ended up in the Prado Museum. In the side aisles were an Immaculate Conception, now in the Louvre, and The Triumph of Faith, in the Faringdon collection.[18]

Other paintings of interest have survived to the present day. The altarpiece of the Pietà, from 1564, has works by Luis de Vargas.[19] A panel of the Ecce Homo is by a follower of Luis de Morales.[19]

Main altarpiece

In 1657, Canon Justino de Neve, as a visitor of the chapels of the cathedral of Seville, notified the town council that he had collected alms for the construction of a new main altarpiece. On August 31, 1657, Martín Moreno, a master assembler who had already executed the choir stalls of this church, was contracted for its execution.[20]

This baroque altarpiece consists of a very carved bench with floral themes, as well as the side streets, where the silver tabernacle is located, flanked by the carvings of St. Peter and St. Paul. The images are framed by pairs of Doric order columns and then follow a body, framed by two Solomonic columns, with an Attic base. In the upper part, there are carvings of seraphs. Recently a crucifix has been added, attributed to Juan de Mesa, dated around 1620.[20]

Brotherhoods

The Antigua y Fervorosa Hermandad del Rosario de María Santísima Nuestra Señora de las Nieves[21] has its headquarters in the church. It is a brotherhood of glory. Its first rules date from 1732. The Virgin of the Snows (Virgen de las Nieves) was made in the 19th century by Juan de Astorga and has been in the brotherhood since 1864.[22]

The Brotherhood of Penitence of the Church of San Isidoro also has the Virgin of the Snows as its patron saint.

The Brotherhood of the Lavatory, Christ of the Mandate, and the Mother of God of the Pópulo were founded in 1598 in the Church of San Esteban and in 1610 moved to the Church of Santa María la Blanca. With the reduction of brotherhoods in 1623, this brotherhood was united with that of the Quinta Angustia, separating in 1624. This brotherhood carried out its penitential station with three floats: one of mystery where the passage of the washing of the feet was represented (of which nothing has been preserved); the float of the Christ of the Mandate, which processed on a carved cliff; and the Virgin of the Pópulo, which came out with a blue velvet canopy supported by ten rods. The last documented penitential procession of this brotherhood dates back to 1662. Illustrious people belonged to this brotherhood, such as the patron Justino de Neve, the writer Fernando de la Torre Farfán, the ceramist Cristóbal de Sepúlveda, the sculptor José Montes de Oca, and noble families of the surroundings such as the Marquises of Villamanrique or the Counts of Altamira.[15]

Bibliography

- Gil Delgado, Oscar (2015) (in es). Arquitectura de Santa María la Blanca: mezquita, sinagoga e iglesia en Sevilla. Editorial University of Seville. ISBN 978-84-472-1809-7.

- Arenillas, Juan Antonio (2005) (in es). Del Clasicismo al Barroco. Arquitectura sevillana del siglo XVII.. Secretariat of Publications of the Provincial Council of Seville. ISBN 84-7798-218-X.

- Falcon Marquez, Teodoro (1988) (in es). «La Iglesia de Santa María la Blanca». Laboratorio de Arte. Journal of the Department of Art History. Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Seville. pp. 117-132.

External links

- This article is a derivative work of the provision relating to the process of declaration or opening of a cultural or natural property published in the BOE No. 291 on December 6, 1995 (text), text that is free of known restrictions under copyright in accordance with the provisions of Article 13 of the Spanish Intellectual Property Law.

- Iglesia de Santa María la Blanca - Sevilla

- Santa Maria la Blanca Church, Seville, Spain

References

- ↑ "El Viernes Santo gana una cofradía en CarmonaCangrejeando | Cangrejeando". 2016-06-18. https://web.archive.org/web/20160618072716/http://blogs.elcorreoweb.es/cangrejeando/2015/03/08/el-viernes-santo-gana-una-cofradia-en-carmona/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Marquez, Falcon (1988) (in es). La Iglesia de Santa Maria la Blanca. pp. 119.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Montoto, Santiago (1950) (in es). Nueva Guía de Sevilla. Plus Ultra. pp. 105.

- ↑ Gil Delgado, Oscar (2013) (in es). Una sinagoga desvelada en Sevilla: estudio arquitectónico. Sefarad. pp. 69-96.

- ↑ Quilés García, Fernando (2005) (in es). Por los caminos de Roma. Miño y Davila. pp. 84.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Iglesia de Santa María la Blanca (Sevilla)" (in es), Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre, 2022-11-15, https://es.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Iglesia_de_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca_(Sevilla)&oldid=147346317, retrieved 2023-05-25

- ↑ Falcon Marquez, Teodoro (1988) (in es). La Iglesia de Santa Maria la Blanca. Laboratorio de Arte. Journal of the Department of Art History. Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Seville.. pp. 117-132.

- ↑ "Last phase of the restoration of the Church of Santa María la Blanca" (in es). 2015-05-13. https://www.archisevilla.org/ultima-fase-de-la-restauracion-de-sta-maria-la-blanca/.

- ↑ Vila Vilar, Enriqueta (1998) (in es). "Something more about Miguel Mañara: the trip to Madrid in 1664".. Bulletin of the Royal Sevillian Academy of Belles Lettres: Minervae Baeticae. pp. 255-281. http://institucional.us.es/revistas/rasbl/26/art_14.pdf.

- ↑ Herrera Garcia, Francisco J. (2020). "Blanquísima señora": immaculist festivities of 1665 in Santa María la Blanca, Seville".. II International Congress on the Descent of the Virgin Mary. pp. 415-444.

- ↑ Sevilla, Diario de (2015-12-01). "Restoration of Santa María la Blanca is completed" (in es-ES). https://www.diariodesevilla.es/sevilla/Concluye-restauracion-Santa-Maria-Blanca_0_976702843.html.

- ↑ ""Our Lady of the Snows" Retablo Cerámico". http://www.retabloceramico.net/0151.htm.

- ↑ Marquez, Falcon (1988) (in es). La Iglesia de Santa Maria la Blanca. pp. 121.

- ↑ Martinez Alcalde, Juan (2009) (in es). Imágenes pasionistas de Sevilla que no procesionan..

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Sevilla, Diario de (2021-09-14). "The Virgin of the Pópulo, exposed to the veneration of the faithful in Santa María la Blanca" (in es-ES). https://www.diariodesevilla.es/sevilla/Virgen-Populo-Santa-Maria-Blanca_0_1610840510.html.

- ↑ Sevilla, Diario de (2021-03-12). "Hermandad de la Virgen del Pópulo: Devociones de la antigua Judería" (in es-ES). https://www.diariodesevilla.es/semana_santa/hermandad-virgen-populo-Devociones-antigua-Juderia_0_1554745042.html.

- ↑ "Restoration of an image of an extinct confraternity in Seville" (in es). 2017-09-18. https://sevilla.abc.es/pasionensevilla/noticias-semana-santa-sevilla/sevi-restauran-una-imagen-de-una-cofradia-extinguida-de-sevilla-117110-1505688186-201709180043_noticia.html.

- ↑ Marquez, Falcon (1988) (in es). La Iglesia de Santa Maria la Blanca. pp. 124-125.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Marquez, Falcon (1988) (in es). La Iglesia de Santa Maria la Blanca. pp. 120.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Falcon Marquez, Teodoro (2013) (in es). «El arquitecto de retablos y escultor Martín Moreno y los primeros retablos con columnas salomónicas en Sevilla» (Boletin de Arte ed.). Malaga Univeristy. pp. 34.

- ↑ "Our Lady of the Snows". http://www.hermandades-de-sevilla.org/ntra-sra-de-las-nieves.

- ↑ Falcon Marquez, Teodoro (in es). "Altarpieces and sculptures of the Church of Santa María la Blanca in Seville".. Laboratorio de arte. Journal of the Department of Art History. Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Seville.. pp. 301-320.