Religion:Concupiscence

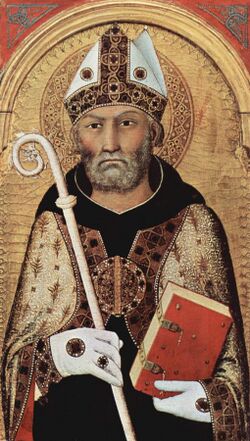

| Part of a series on |

| Thomas Aquinas |

|---|

|

|

|

Concupiscence (from Late Latin concupīscentia, from the Latin verb concupīscere, from con-, "with", here an intensifier, + cupere, "to desire" + -scere, a verb-forming suffix denoting beginning of a process or state) is an ardent longing, typically one that is sensual.[1] In Christianity, particularly in Catholic and Lutheran theology, concupiscence is the tendency of humans to sin.[2][3]

There are nine occurrences of concupiscence in the Douay-Rheims Bible[4] and three occurrences in the King James Bible.[5] It is also one of the English translations of the Koine Greek epithumia (ἐπιθυμία),[6] which occurs 39 times in the New Testament.[7]

Involuntary sexual arousal is explored in the Confessions of Augustine, wherein he used the term "concupiscence" to refer to sinful lust.[8]

Jewish perspective

In Judaism, there is an early concept of yetzer hara (Hebrew: יצר הרע for "evil inclination"). This concept is the inclination of humanity at creation to do evil or violate the will of God. The yetzer hara is not the product of original sin as in Christian theology, but the tendency of humanity to misuse the natural survival needs of the physical body. Therefore, the natural need of the body for food becomes gluttony, the command to procreate becomes sexual sin, the demands of the body for rest become sloth, and so on.[citation needed]

In Judaism, the yetzer hara is a natural part of God's creation, and God provides guidelines and commands to help followers master this tendency. This doctrine was clarified in the Sifre around 200–350 CE. In Jewish doctrine, it is possible for humanity to overcome the yetzer hara. Therefore, for the Jewish mindset, it is possible for humanity to choose good over evil and it is the person's duty to choose good (cf. Sifrei on Deuteronomy, P. Ekev 45, Kidd. 30b).

Augustine

Involuntary sexual arousal is explored in the Confessions of Augustine, wherein he used the term "concupiscence" to refer to sinful lust.[8] He taught that Adam's sin[lower-alpha 1] is transmitted by concupiscence, or "hurtful desire",[9][10] resulting in humanity becoming a massa damnāta (mass of perdition, condemned crowd), with much enfeebled, though not destroyed, freedom of will.[11] When Adam sinned, human nature was thenceforth transformed. Adam and Eve, via sexual reproduction, recreated human nature. Their descendants now live in sin, in the form of concupiscence, a term Augustine used in a metaphysical, not a psychological sense.[lower-alpha 2] Augustine insisted that concupiscence was not a being but a bad quality, the privation of good or a wound.[12] He admitted that sexual concupiscence (libīdō) might have been present in the perfect human nature in paradise and that only later it became disobedient to human will as a result of the first couple's disobedience to God's will in the original sin.[lower-alpha 3][13] In Augustine's view (termed "Realism"), all of humanity was really present in Adam when he sinned and therefore all have sinned. Original sin, according to Augustine, consists of the guilt of Adam which all humans inherit.

Pelagius

The main opposition came from a monk named Pelagius (354–420 or 440). His views became known as Pelagianism. Although the writings of Pelagius are no longer extant, the eight canons of the Council of Carthage (418) provided corrections to the perceived errors of the early Pelagians. From these corrections, there is a strong similarity between Pelagians and their Jewish counterparts on the concepts of concupiscence. Pelagianism gives mankind the ability to choose between good and evil within their created nature. While rejecting concupiscence, and embracing a concept similar to the yetzer hara, these views rejected humanity's universal need for grace.

Catholic teaching

The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) teaches that Adam and Eve were constituted in an original "state of holiness and justice" (CCC 375, 376 398), free from concupiscence (CCC 377). The preternatural state enjoyed by Adam and Eve afforded endowments with many prerogatives which, while pertaining to the natural order, were not due to human nature as such. Principal among these were a high degree of infused knowledge, bodily immortality and freedom from pain, and immunity from evil impulses or inclinations. In other words, the lower or animal nature in man was perfectly subject to the control of reason and the will subject to God. Besides this, the Catholic Church teaches that our first parents were also endowed with sanctifying grace by which they were elevated to the supernatural order.[14] By sinning, however, Adam lost this original "state", not only for himself but for all human beings (CCC 416).

According to Catholic theology, man has not lost his natural faculties: by the sin of Adam he has been deprived only of the divine gifts to which his nature had no strict right: the complete mastery of his passions, exemption from death, sanctifying grace, and the vision of God in the next life. God the Father, whose gifts were not due to the human race, had the right to bestow them on such conditions as He wished and to make their conservation depend on the fidelity of the head of the family. A prince can confer a hereditary dignity on condition that the recipient remains loyal and that, in case of his rebelling, this dignity shall be taken from him and in consequence from his descendants. It is not, however, intelligible that the prince, on account of a fault committed by a father, should order the hands and feet of all the descendants of the guilty man to be cut off immediately after their birth.[15]

As a result of original sin, according to Catholics, human nature has not been totally corrupted (as opposed to the teachings of Luther and Calvin); rather, human nature has only been weakened and wounded, subject to ignorance, suffering, the domination of death, and the inclination to sin and evil (CCC 405, 418). This inclination toward sin and evil is called "concupiscence" (CCC 405, 418). Baptism, the Catechism teaches, erases original sin and turns a man back towards God. The inclination toward sin and evil persists, however, and he must continue to struggle against concupiscence (CCC 2520).

Today, the Catholic Church's teaching on original sin focuses more on its results than on its origins. As Cardinal Ratzinger had intimated in 1981,[16][unreliable source?] and as Pope Benedict XVI clarified in 2008: "How did it happen? This remains obscure.... Evil remains mysterious. It is presented as such in great images, as it is in chapter 3 of Genesis, with that scene of the two trees, of the serpent, of sinful man: a great image that makes us guess but cannot explain what is itself illogical."[17]

Methodist teaching

The Wesleyan–Arminian theology of the Methodist Churches, inclusive of the Wesleyan-Holiness movement, teaches that humans, though being born with original sin, can turn to God as a result of prevenient grace and do good; this prevenient grace convicts humans of the necessity of the new birth (first work of grace), through which he is justified (pardoned) and regenerated.[18] After this, to willfully sin would be to fall from grace, though a person can be restored to fellowship with God through repentance.[18][19] When the believer is entirely sanctified (second work of grace), his/her original sin is washed away.[18] Methodist theology firstly distinguishes between original sin and actual sin:[20]

Original sin is the sin which corrupts our nature and gives us the tendency to sin. Actual sins are the sins we commit every day before we are saved, such as lying, swearing, stealing.[20]

It further categorizes sin as being "sin proper" and "sin improper".[18] Sins proper (or sin, properly so called) are those that are committed freely and willfully, which result in a loss of entire sanctification.[21][18][22] Sins improper (or sin, improperly so called) are those in the "category of benign neglect, fruits of infirmity (forgetfulness, lack of knowledge, etc)".[18] In traditional Methodist theology, these (improper) sins are not classified as sins, as explained by Wesley, "Such transgressions you may call sins, if you please: I do not, for the reasons above-mentioned."[23] John Wesley explains the matter like this:[24]

"Nothing is sin, strictly speaking, but a voluntary transgression of a known law of God. Therefore, every voluntary breach of the law of love is sin; and nothing else, if we speak properly. To strain the matter farther is only to make way for Calvinism. There may be ten thousand wandering thoughts, and forgetful intervals, without any breach of love, though not without transgressing the Adamic law. But Calvinists would fain confound these together. Let love fill your heart, and it is enough!"[24]

Although an entirely sanctified person is not free from temptation, "the entirely sanctified person does have the distinct advantage of a pure heart and the fullness of the Holy Spirit's presence to give strength in resisting temptation."[25] If a person backslides through sin proper but later returns to God, he or she must repent and be entirely sanctified again, according to Wesleyan-Arminian theology.[26]

Comparison of the Catholic view with Lutheran, Reformed and Anglican views

The primary difference between Catholic theology and Lutheran, Reformed and Anglican theologies on the issue of concupiscence is whether it can be classified as sin by its own nature. The Catholic Church teaches that while it is highly likely to cause sin, concupiscence is not sin itself. Rather, it is "the tinder for sin" which "cannot harm those who do not consent" (CCC 1264).[27]

This difference is intimately tied with the different traditions on original sin. Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican theology holds that the original prelapsarian nature of humanity was an innate tendency to good; the special relationship Adam and Eve enjoyed with God was due not to some supernatural gift, but to their own natures. Hence, in these traditions, the Fall was not the destruction of a supernatural gift, leaving humanity's nature to work unimpeded, but rather the corruption of that nature itself. Since the present nature of humans is corrupted from their original nature, it follows that it is not good, but rather evil (although some good may still remain). Thus, in these traditions, concupiscence is evil in itself. The Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England state that "the Apostle doth confess, that concupiscence and lust hath of itself the nature of sin".[28]

By contrast, Catholicism, while also maintaining that humanity's original nature is good (CCC 374), teaches that even after this gift was lost after the Fall, human nature still cannot be called evil, because it remains a natural creation of God. Despite the fact that humans sin, Catholic theology teaches that human nature itself is not the cause of sin, although once it comes into contact with sin it may produce more sin.

The difference in views also extends to the relationship between concupiscence and original sin.

Another reason for the differing views of Catholics with Lutherans, Reformed, and Anglicans on concupiscence is their position on sin in general. The Magisterial Reformers taught that one can be guilty of sin even if it is not voluntary; the Catholic Church and the Methodist Church, by contrast, traditionally hold that one is guilty of sin only when the sin is voluntary. The Scholastics and magisterial reformers have different views on the issue of what is voluntary and what is not: the Catholic Scholastics considered the emotions of love, hate, like and dislike to be acts of will or choice, while the early Protestant reformers did not. [citation needed] By the Catholic position that one's attitudes are acts of will, sinful attitudes are voluntary. By the magisterial reformer view that these attitudes are involuntary, some sins are involuntary as well.

Some denominations may relate concupiscence to "humanity's sinful nature" in order to distinguish it from particular sinful acts.

Sensuality

Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century described two divisions of "sensuality": the concupiscible (pursuit/avoidance instincts) and the irascible (competition/aggression/defense instincts). With the former are associated the emotions of joy and sadness, love and hate, desire and repugnance; with the latter, daring and fear, hope and despair, anger.

Islam

Al-Ghazali in the 11th century discussed concupiscence from an Islamic perspective in his book Kimiya-yi sa'ādat (The Alchemy of Happiness), and also mentioned it in The Deliverer from Error. In this book, amongst other things, he discusses how to reconcile the concupiscent and the irascible souls, balancing them to achieve happiness. Concupiscence is related to the term "nafs" in Arabic.[29]

See also

- Ancestral sin

- Flesh (theology)

- Hamartiology

- Incurvatus in se

- Lust

- Prevenient grace

- Seven deadly sins

References

Citations

- ↑ "Concupiscence – Define Concupiscence at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com. http://dictionary.reference.com/search?q=Concupiscence&x=0&y=0.

- ↑ Malloy, Christopher J. (2005) (in English). Engrafted Into Christ: A Critique of the Joint Declaration. Peter Lang. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-8204-7408-3. "The Annex offers the following description of the Catholic notion of voluntary sin: "Sin has a personal character and as such leads to separation from God. It is the selfish desire of the old person and the lack of trust and love toward God." The Annex also offers the following as a Lutheran position: Concupiscence is understood as the self-seeking desire of the human being, which in light of the law, spiritually understood, is regarded as sin." A comparison of the two descriptions, one of sin and one of concupiscence, shows little if any difference. The Catholic definition of voluntary sin includes the following elements: selfish desire and lack of love. Those of the Lutheran conception of concupiscence are selfish desire, lack of love, and repeated idolatry—a sin which, as stated in the JD, requires daily forgiveness (JD, 29). The Catholic definition of sin appears quite similar to the Lutheran definition of concupiscence."

- ↑ Coleman, D. (11 October 2007) (in English). Drama and the Sacraments in Sixteenth-Century England: Indelible Characters. Springer. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-230-58964-3. "Trent defines concupiscence as follows: Concupiscence or a tendency to sin remains [after baptism, but] the catholic church has never understood it to be called sin in the sense of being truly and properly such in those who have been regenerated, but in the sense that it is a result of sin and inclines to sin (667*)."

- ↑ Wisdom 4:12, Romans 7:7, Romans 7:8, Colossians 3:5, Epistle of James 1:14, James 1:15, 2 Peter 1:4, and 1 John 2:17.

- ↑ Romans 7:8, Colossians 3:5 and I Thessalonians 4:5.

- ↑ "epithumia" is also translated as wish or desire (or in a biblical context, longing, lust, passion, covetousness, or impulse). See wikt:επιθυμία.

- ↑ Matthew 5:29–30, Mark 4:19, Luke 22:15, John 8:44, Romans 1:24, Romans 6:12, Romans 7:7,8, Romans 13:14, Galatians 5:16,24, Ephesians 2:3, Ephesians 4:22, Philippians 1:23, Colossians 3:5, 1Thessalonians 2:17, 1Thessalonians 4:5, 1Timothy 6:9, 2Timothy 2:22, 2Timothy 3:6, 2Timothy 4:3, Titus 2:12, Titus 3:3, James 1:14,15, 1Peter 1:14, 1Peter 2:11, 1Peter 4:2,3, 2Peter 1:4, 2Peter 2:10,18, 2Peter 3:3, 1John 2:16(twice),17, Jude 1:16,18, and Revelation 18:14.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Greenblatt, Stephen (June 19, 2017). "How St. Augustine Invented Sex". The New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/06/19/how-st-augustine-invented-sex.

- ↑ ORIGINAL SIN - Biblical Apologetic Studies – Retrieved 17 May 2014. Augustine of Hippo (354–430) taught that Adam's sin is transmitted by concupiscence, or "hurtful desire", sexual desire and all sensual feelings resulting in humanity becoming a massa damnata (mass of perdition, condemned crowd), with much enfeebled, though not destroyed, freedom of will.

- ↑ William Nicholson – A Plain But Full Exposition of the Catechism of the Church of England... (Google eBook) page 118. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ↑ ODCC 2005, p. Original sin.

- ↑ Non substantialiter manere concupiscentiam, sicut corpus aliquod aut spiritum; sed esse affectionem quamdam malae qualitatis, sicut est languor. (De nuptiis et concupiscentia, I, 25. 28; PL 44, 430; cf. Contra Julianum, VI, 18.53; PL 44, 854; ibid. VI, 19.58; PL 44, 857; ibid., II, 10.33; PL 44, 697; Contra Secundinum Manichaeum, 15; PL 42, 590.

- ↑ Schmitt, É. (1983). Le mariage chrétien dans l'oeuvre de Saint Augustin. Une théologie baptismale de la vie conjugale. Études Augustiniennes. Paris. p. 104.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: The Garden of Eden". Newadvent.org. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14519a.htm.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Original Sin". Newadvent.org. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11312a.htm.

- ↑ ""Cardinal" Ratzinger denies Original Sin" (in en-US). http://novusordowatch.org/cardinal-ratzinger-denies-original-sin/.

- ↑ "General Audience of 3 December 2008: Saint Paul (15). The Apostle's teaching on the relation between Adam and Christ | BENEDICT XVI". https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20081203.html.

- ↑ Long, D. Stephen (1 March 2012) (in English). Keeping Faith: An Ecumenical Commentary on the Articles of Religion and Confession of Faith in the Wesleyan Tradition. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-62189-416-2.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Rothwell, Mel-Thomas; Rothwell, Helen (1998) (in en). A Catechism on the Christian Religion: The Doctrines of Christianity with Special Emphasis on Wesleyan Concepts. Schmul Publishing Co.. p. 49.

- ↑ Brown, Allan (1 June 2008). "Questions About Entire Sanctification" (in en). God's Bible School and College. https://www.gbs.edu/questions-about-entire-sanctification/. "The only way a person can “lose” (“reject” is a better term) his entire sanctification is through willful sin or unbelief (which is also sin)."

- ↑ Trinklein, John (1 August 2016). "Holiness Unto Whom? John Wesley 's Doctrine of Entire Sanctification in Light of The Two Kinds of Righteousness" (in en). Concordia Seminary. https://scholar.csl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1024&context=phd.

- ↑ Wesley, John (1872). The Works of John Wesley., Third Edition., vol. 11. London: Wesleyan Methodist Book Room. pp. 396.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Wesley, J. (1872). The Works of John Wesley (Third Edition, Vol. 12, p. 394). London: Wesleyan Methodist Book Room.

- ↑ Burnett, Daniel L. (15 March 2006) (in English). In the Shadow of Aldersgate: An Introduction to the Heritage and Faith of the Wesleyan Tradition. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-62189-980-8.

- ↑ Brown, Allan P. (1 June 2008). "Questions About Entire Sanctification" (in en). https://www.gbs.edu/questions-about-entire-sanctification/. "Does an entirely sanctified person who rebels against God but later comes back to Him need to be entirely sanctified again? We do know that a person can rebel against God and later turn back in repentance and then be “re-saved.” Answer: Yes. To come back to God is the action of a backslider having his re in need of continual cleansing. The verb “cleanses us” is a present indica-relationship with God restored. After the restoration, one must walk in the light and obey Romans 12:1 and offer himself a living, holy, and acceptable sacrifice to God. This can be done only by a person in right relationship with God."

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, New York: Doubleday Publications, 1997

- ↑ Church of England (1562), "Articles", Common Prayer, https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-worship/worship/book-of-common-prayer/articles-of-religion.aspx, retrieved 2016-03-16

- ↑ "The Alchemy of Happiness Index". Sacred-texts.com. http://www.sacred-texts.com/isl/tah/index.htm.

- Cross, Frank L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds (2005). Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- Robert Merrihew Adams, "Original Sin: A Study in the Interaction of Philosophy and Theology", p. 80ff in Francis J. Ambrosio (ed.), The Question of Christian Philosophy Today, Fordham University Press (New York: 1999), Perspectives in Continental Philosophy no. 9.

- Joseph A. Komonchak, Mary Collins, and Dermot A. Lane, eds., The New Dictionary of Theology (Wilmington, Delaware : Michael Glazier, Inc., 1987), p. 220.

- New Advent (Catholic Encyclopedia), "Concupiscence". http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04208a.htm.

- Adam Smith, Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence Vol. 1 The Theory of Moral Sentiments [1759]] Part VII Section II Chapter I Paragraphs 1–9, Adam Smith's recounting of Plato's description of the soul, including concupiscence

Notes

- ↑ Augustine taught that Adam's sin was both an act of foolishness (īnsipientia) and of pride and disobedience to God of Adam and Eve. He thought it was a most subtle job to discern what came first: self-centeredness or failure in seeing truth. Augustine wrote to Julian of Eclanum: Sed si disputatione subtilissima et elimatissima opus est, ut sciamus utrum primos homines insipientia superbos, an insipientes superbia fecerit (Contra Julianum, V, 4.18; PL 44, 795). This particular sin would not have taken place if Satan had not sown into their senses "the root of evil" (radix mali): Nisi radicem mali humanus tunc reciperet sensus (Contra Julianum, I, 9.42; PL 44, 670)

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas explained Augustine's doctrine pointing out that the libido (concupiscence), which makes the original sin pass from parents to children, is not a libido actualis, i.e. sexual lust, but libido habitualis, i.e. a wound of the whole of human nature: Libido quae transmittit peccatum originale in prolem, non est libido actualis, quia dato quod virtute divina concederetur alicui quod nullam inordinatam libidinem in actu generationis sentiret, adhuc transmitteret in prolem originale peccatum. Sed libido illa est intelligenda habitualiter, secundum quod appetitus sensitivus non continetur sub ratione vinculo originalis iustitiae. Et talis libido in omnibus est aequalis (STh Iª–IIae q. 82 a. 4 ad 3).

- ↑ Augustine wrote to Julian of Eclanum: Quis enim negat futurum fuisse concubitum, etiamsi peccatum non praecessisset? Sed futurus fuerat, sicut aliis membris, ita etiam genitalibus voluntate motis, non libidine concitatis; aut certe etiam ipsa libidine – ut non vos de illa nimium contristemus – non qualis nunc est, sed ad nutum voluntarium serviente (Contra Julianum, IV. 11. 57; PL 44, 766). See also his late work: Contra secundam Iuliani responsionem imperfectum opus, II, 42; PL 45,1160; ibid. II, 45; PL 45,1161; ibid., VI, 22; PL 45, 1550–1551.

|