Religion:Historical Jesus

The term historical Jesus refers to attempts to "reconstruct the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth by critical historical methods", in "contrast to Christological definitions ('the dogmatic Christ') and other Christian accounts of Jesus ('the Christ of faith')."[1] It also considers the historical and cultural context in which Jesus lived.[2][3][4]

Virtually all scholars who write on the subject agree that Jesus existed,[5][6][7][8] although scholars differ about the beliefs and teachings of Jesus as well as the accuracy of the biblical accounts, and the only two events subject to "almost universal assent" are that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist and was crucified by the order of the Roman Prefect Pontius Pilate.[9][10][11][12] Historical Jesus scholars typically contend that he was a Galilean Jew living in a time of messianic and apocalyptic expectations.[13][14] Some scholars credit the apocalyptic declarations of the gospels to him, while others portray his "Kingdom of God" as a moral one, and not apocalyptic in nature.[15]

Since the 18th century, three separate scholarly quests for the historical Jesus have taken place, each with distinct characteristics and developing new and different research criteria.[16][17] The portraits of Jesus that have been constructed in these processes have often differed from each other, and from the dogmatic image portrayed in the gospel accounts.[18] These portraits include that of Jesus as an apocalyptic prophet, charismatic healer, Cynic philosopher, Jewish messiah and prophet of social change,[19][20] but there is little scholarly agreement on a single portrait, or the methods needed to construct it.[18][21][22] There are, however, overlapping attributes among the various portraits, and scholars who differ on some attributes may agree on others.[19][20][23]

A number of scholars have criticized the various approaches used in the study of the historical Jesus—on one hand, for the lack of rigor in research methods; on the other, for being driven by "specific agendas" that interpret ancient sources to fit specific goals.[24] [25][26] By the 21st century, the "maximalist" approaches of the 19th century which accepted all the gospels and the "minimalist" trends of the early 20th century which totally rejected them were abandoned and scholars began to focus on what is historically probable and plausible about Jesus.[27][28][29]

History

The scholarly effort to reconstruct an "authentic" historical picture of Jesus was a product of the Enlightenment skepticism of the late eighteenth century.[18] : 1 Bible scholar Gerd Theissen explains "It was concerned with presenting a historically true life of Jesus that functioned theologically as a critical force over against [established Roman Catholic] Christology."[18]: 1 The first scholar to separate the historical Jesus from the theological Jesus in this way was philosopher, writer, classicist, Hebraist and Enlightenment free thinker Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694–1768).[30] Copies of Reimarus' writings were discovered by G. E. Lessing (1729–1781) in the library at Wolfenbüttel where Lessing was the librarian. Reimarus had left permission for his work to be published after his death, and Lessing did so between 1774 and 1778, publishing them as Die Fragmente eines unbekannten Autors (The Fragments of an Unknown Author). Over time, they came to be known as the Wolfenbüttel Fragments after the library where Lessing worked. Reimarus distinguished between what Jesus taught and how he is portrayed in the New Testament. According to Reimarus, Jesus was a political Messiah who failed at creating political change and was executed. His disciples then stole the body and invented the story of the resurrection for personal gain.[30][31]: 46–48 Reimarus' controversial work prompted a response from "the father of historical critical research" Johann Semler in 1779, Beantwortung der Fragmente eines Ungenannten (Answering the Fragments of an Unknown).[32]: 43–45, 355–359 Semler refuted Reimarus' arguments, but it was of little consequence. Reimarus' writings had already made lasting changes by making it clear criticism could exist independently of theology and faith, and by founding historical Jesus studies within that non-sectarian view.[33]: 346–350 [31]: 48

Since the 18th century, three scholarly quests for the historical Jesus have taken place, each with distinct characteristics and based on different research criteria, which were often developed during each specific phase.[16][34][17] These quests are distinguished from pre-Enlightenment approaches because they rely on the historical method to study biblical narratives. While textual analysis of biblical sources had taken place for centuries, these quests introduced new methods and specific techniques in the attempt to establish the historical validity of their conclusions.[35]

The enthusiasm shown during the first quest diminished after Albert Schweitzer's critique of 1906 in which he pointed out various shortcomings in the approaches used at the time. The second quest began in 1953 and introduced a number of new techniques, but reached a plateau in the 1970s.[36] In the 1980s a number of scholars gradually began to introduce new research ideas,[16][37] initiating a third quest characterized by the latest research approaches.[36][38] One of the modern aspects of the third quest has been the role of archaeology; James Charlesworth states that modern scholars now want to use archaeological discoveries that clarify the nature of life in Galilee and Judea during the time of Jesus.[39] A further characteristic of the third quest has been the interdisciplinary and global nature of its scholarship.[40] While the first two quests were mostly carried out by European Protestant theologians, a modern aspect of the third quest is the worldwide influx of scholars from multiple disciplines.[40] More recently, historicists have focused their attention on the historical writings associated with the era in which Jesus lived[41][42] or on the evidence concerning his family.[43][44][45]

After Schweitzer's Von Reimarus zu Wrede was translated and published in English as The Quest of the historical Jesus in 1910, the book's title provided the label for the field of study for eighty years.[46]: 779- By the end of the twentieth century, scholar Tom Holmén writes that Enlightenment skepticism had given way to a more "trustful attitude toward the historical reliability of the sources. ...[Currently] the conviction of Sanders, (we know quite a lot about Jesus) characterizes the majority of contemporary studies."[47]: 43 Reflecting this shift, the phrase "quest for the historical Jesus" has largely been replaced by life of Jesus research.[48]: 33

Methods

The first quest, which started in 1778, was almost entirely based on biblical criticism. This took the form of textual and source criticism originally, which were supplemented with form criticism in 1919, and redaction criticism in 1948.[35] Form criticism began as an attempt to trace the history of the biblical material during the oral period before it was written in its current form, and may be seen as starting where textual criticism ends.[49] Form criticism views Gospel writers as editors, not authors. Redaction criticism may be viewed as the child of source criticism and form criticism.[50] and views the Gospel writers as authors and early theologians and tries to understand how the redactor(s) has (have) molded the narrative to express their own perspectives.[50]

When form criticism questioned the historical reliability of the Gospels, scholars began looking for other criteria. Taken from other areas of study such as source criticism, the "criteria of authenticity" emerged gradually, becoming a distinct branch of methodology associated with life of Jesus research.[47]: 43–54 The criteria are a variety of rules used to determine if some event or person is more or less likely to be historical. These criteria are primarily, though not exclusively, used to assess the sayings and actions of Jesus.[51]: 193–199 [52]: 3–33

In view of the skepticism produced in the mid-twentieth century by form criticism concerning the historical reliability of the gospels, the burden shifted in historical Jesus studies from attempting to identify an authentic life of Jesus to attempting to prove authenticity. The criteria developed within this framework, therefore, are tools that provide arguments solely for authenticity, not inauthenticity.[47]: 43 In 1901, the application of criteria of authenticity began with dissimilarity. It was often applied unevenly with a preconceived goal.[18]: 1 [47]: 40–45 In the early decades of the twentieth century, F.C. Burkitt and B.H. Streeter provided the foundation for multiple attestation. The second Quest introduced the criterion of embarrassment.[35] By the 1950's, coherence was also included. By 1987, D.Polkow lists 25 separate criteria being used by scholars to test for historical authenticity including the criterion of "historical plausibility".[35][51]: 193–199

The criterion of multiple attestation or independent attestation, sometimes also referred to as the cross-sectional method, is a type of source criticism first developed by F. C. Burkitt in 1911. Simply put, the method looks for commonalities in multiple sources with the assumption that, the more sources that report an event or saying, the more likely that event or saying is historically accurate. Burkitt claimed he found 31 independent sayings in Mark and Q. Within Synoptic Gospel studies, this was used to develop the four-source hypothesis. Multiple sources lend support to some level of historicity. New Testament scholar Gerd Theissan says "there is broad scholarly consensus that we can best find access to the historical Jesus through the Synoptic tradition."[53]: 25 [54]: 83 [55] A second related theory is that of multiple forms. Developed by C. H. Dodd, it focuses on the sayings or deeds of Jesus found in more than one literary form. Bible scholar Andreas J. Köstenberger gives the example of Jesus proclaiming the kingdom of God had arrived. He says it is found in an "aphorism (Mat.5:17), in parables (Mat.9:37–38 and Mark 4:26–29), poetic sayings (Mat.13:16–17), and dialogues (Mat.12:24–28)" and is therefore likely an authentic theme of Jesus' teaching.[56]: 149 [57]: 90–91 [58]: 174–175, 317 [59][60]

The criterion of embarrassment is based on the assumption the early church would not have gone out of its way to "create" or "falsify" historical material that only embarrassed its author or weakened its position in arguments with opponents.[61]: 54–56 As historian Will Durant explains:

Despite the prejudices and theological preconceptions of the evangelists, they record many incidents that mere inventors would have concealed—the competition of the apostles for high places in the Kingdom, their flight after Jesus' arrest, Peter's denial, the failure of Christ to work miracles in Galilee, the references of some auditors to his possible insanity, his early uncertainty as to his mission, his confessions of ignorance as to the future, his moments of bitterness, his despairing cry on the cross.[62]: 557

These and other possibly embarrassing events, such as the discovery of the empty tomb by women, Jesus' baptism by John, and the crucifixion itself, are seen by this criterion as lending credence to the supposition the gospels contain some history.[62][63][61] The criterion of the crucifixion is related to the criterion of embarrassment. In the first-century Roman empire, only criminals were crucified. The early church referred to death on the cross as a scandal. It is therefore unlikely to have been invented by them.[64]: 139, 140 [60]: 239 [63]

New Testament scholar Gerd Theissen and theologian Dagmar Winter say one aspect of the criterion of embarrassment is "resistance to tendencies of the tradition".[60]: 239 It works on the assumption that what goes against the general tendencies of the early church is historical. For example, criticisms of Jesus go against the tendency of the early church to worship him, making it unlikely the early church community invented statements such as those accusing Jesus of being in league with Satan (Matthew 12:24), or being a glutton and drunkard (Matthew 11:19). Theissen and Winter sum this up with what can also be referred to as enemy attestation: when friends and enemies alike refer to the same events, those events are likely to be historical.[60]: 240

The criterion of dissimilarity or discontinuity says that if a particular saying can be plausibly accounted for as the words or teaching of some other source contemporary to Jesus, it is not thought to be genuine evidence of the historical Jesus. The "Son of Man" sayings are an example. Judaism had a Son of Man concept (as indicated by texts like 1 Enoch 46:2; 48:2–5,10; 52:4; 62:5–9; 69:28–29 and 4 Ezra 13:3ff), but there is no record of the Jews ever applying it to Jesus. The Son of Man is Jesus' most common self-designation in the Gospels, yet none of the New Testament epistles use this expression, nor is there any evidence that the disciples or the early church did. The conclusion is that, by the process of elimination of all other options, it is likely historically accurate that Jesus used this designation for himself.[65]: 202 [66]: 489–532, 633–636

The criterion of coherence (also called criterion of consistency or criterion of conformity) can be used only when other material has been identified as authentic. This criterion holds that a saying or action attributed to Jesus may be accepted as authentic if it coheres with other sayings and actions already established as authentic. While this criterion cannot be used alone, it can broaden what scholars believe Jesus said and did.[61]: 54–56 [57]: 90 [58]: 174 For example, Jesus' teaching in Mark 12:18–27 concerning the resurrection of the dead coheres well with a saying of Jesus in Q on the same subject of the afterlife (reported in Matthew 8:11–12/Luke 13:28–29), as well as other teachings of Jesus on the same subject.[65]: 69–72

The New Testament contains a high number of words and phrases called Semitisms: a combination of poetic or vernacular koine Greek with Hebrew and Aramaic influences.[67]: 112 [68]: 52–68 A Semitism is the linguistic usage, in the Greek in a non-Greek fashion, of an expression or construction typical of Hebrew or Aramaic. In other words, a Semitism is Greek in Hebrew or Aramaic style.[68]: 53 [67]: 111–114 For example, Matthew begins with a Hebrew gematria (a method of interpreting Hebrew by computing the numerical value of words). In Matthew 1:1, Jesus is designated "the son of David, the son of Abraham". The numerical value of David's name in Hebrew is 14; so this genealogy has 14 generations from Abraham to David, 14 from David to the Babylonian exile, and 14 from the exile to the Christ (Matthew 1:17).[68]: 54 Such linguistic peculiarities tie New Testament texts to Jews of 1st-century Palestine.[68] : 53

Criticism

Bias

Bible scholar Clive Marsh[69] has stated construction of the portraits of Jesus has often been driven by "specific agendas" and that historical components of the relevant biblical texts are often interpreted to fit specific goals.[26] Marsh lists theological agendas that aim to confirm the divinity of Jesus, anti-ecclesiastical agendas that aim to discredit Christianity, and political agendas that aim to interpret the teachings of Jesus with the hope of causing social change.[26][70]

A number of scholars have criticized historical Jesus research for religious bias, and some have argued that modern biblical scholarship is insufficiently critical and sometimes amounts to covert apologetics.[71][72] John P. Meier, a Catholic priest and a professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame, has stated "... I think a lot of the confusion comes from the fact that people claim they are doing a quest for the historical Jesus when de facto they’re doing theology, albeit a theology that is indeed historically informed ..."[73] Meier also wrote that in the past the quest for the historical Jesus has often been motivated more by a desire to produce an alternate Christology than a true historical search.[25]

Historian Michael Licona says a number of scholars have also criticized historical Jesus research for a "secular bias that ...often goes unrecognized to the extent such beliefs are ...considered to be undeniable truths." New Testament scholar Scot McKnight notes that bias is a universal criticism: "everyone tends to lean toward their own belief system" though historian Michael Grant notes that within life of Jesus studies the "notorious problem reaches its height." [74]: 50, 41 Licona adds that because "there is no such thing as an unbiased reader/author," and that every scholar of the historical Jesus "brings philosophical baggage," and because there are no "impartial historians," and "only the naive maintain that historians who are agnostics, atheists and non-Christian theists... [are] without any biases," this is a criticism inevitably accurate to varying degrees for everyone in the field.[74]: 31–104 Stephen Porter says "We are all very biased observers, and given how biased we are, it is no wonder that our criteria so often give us what we want."[75]: 19–20

The New Testament scholar Nicholas Perrin has argued that since most biblical scholars are Christians, a certain bias is inevitable, but he does not see this as a major problem.[76][77] Licona quotes N. T. Wright:

It must be asserted most strongly that to discover that a particular writer has a bias tells us nothing whatever of the value of the particular information he or she presents. It merely bids us be aware of the bias (and of our own for that matter), and to assess the material according to as many sources as we can."[74]: 46, footnote 70

Historian Thomas L. Haskell explains, "even a polemicist, deeply and fixedly committed" can be objective "insofar as such a person successfully enters into the thinking of his or her rivals and produces arguments potentially compelling, not only to those who potentially share the same views, but to outsiders as well."[74]: 50 [78] This has led Licona to recognize 6 tools/methods used to check bias.[74]: 52–61

- Method—attention to method reduces bias

- Making point of view (horizon) and method public allows scrutiny of, and challenges to, that which stands behind the narrative

- Peer pressure—can act as a check, but can also hinder

- Submit work to the unsympathetic—they look for issues the sympathetic overlook

- Account for relevant historical bedrock—some facts are established

- Detachment from bias—historians must force themselves to confront all data

Lack of methodological soundness

A number of scholars have criticized the various approaches used in the study of the historical Jesus: for the lack of rigor in research methods, and for being driven by "specific agendas" that interpret ancient sources to fit specific goals.[24][25][26][27][28][29] New Testament scholar John Kloppenborg Verbin says the lack of uniformity in the application of the criteria, and the absence of agreement on methodological issues concerning them, have created challenges and problems. For example, the question of whether dissimilarity or multiple attestation should be given more weight has led some scholars exploring the historical Jesus to come up with "wildly divergent" portraits of him, which would be less likely to occur if the criteria were prioritized consistently.[79]: 10–31 Methodological alternatives involving hermeneutics, linguistics, cultural studies and more, have been put forth by various scholars as alternatives to the criteria, but so far, the criteria remain the most common method used to measure historicity even though there is still no definitive criteriology.[80]: xi [47]: 45

The historical analysis techniques used by biblical scholars have been questioned,[24][25][26] and according to James Dunn it is not possible "to construct (from the available data) a Jesus who will be the real Jesus."[81][82][83] Classicist historian A. N. Sherwin-White "noted that approaches taken by biblical scholars differed from those of classical historians."[74]: 17–18 Historian Michael R. Licona says biblical scholars are not trained historians for the most part. He asks, "How many have completed so much as a single undergraduate course pertaining to how to investigate the past?"[74]: 19 Licona says N. T. Wright, James G. D. Dunn, and Dale Allison have written substantive historically minded works using hermeneutics, but even so, there remains "no carefully defined and extensive historical method...typical of professional historians."[74]: 20

Donald Akenson, Professor of Irish Studies in the department of history at Queen's University has argued that, with very few exceptions, the historians attempting to reconstruct a biography of the man Jesus of Nazareth apart from the mere facts of his existence and crucifixion have not followed sound historical practices. He has stated that there is an unhealthy reliance on consensus for propositions which should otherwise be based on primary sources, or rigorous interpretation. He also identifies a peculiar downward dating creep, and holds that some of the criteria being used are faulty.[84]

It is difficult for any scholar to construct a portrait of Jesus that can be considered historically valid beyond the basic elements of his life.[85][86] As a result, W.R. Herzog has stated that: "What we call the historical Jesus is the composite of the recoverable bits and pieces of historical information and speculation about him that we assemble, construct, and reconstruct. For this reason, the historical Jesus is, in Meier's words, 'a modern abstraction and construct.'"[87] According to James Dunn, "the historical Jesus is properly speaking a nineteenth and twentieth-century construction, not Jesus back then, and not a figure in history" (emphasis original).[88] Dunn further explains "the facts are not to be identified as data; they are always an interpretation of the data.[89] For example, scholars Chris Keith and Anthony LaDonne point out that under Bultmann and form criticism in the early and mid-twentieth century, Jesus was seen as historically "authentic" only where he was dissimilar from Judaism, whereas, in contemporary studies since the late twentieth, there is near unanimous agreement that Jesus must be understood within the context of first century Judaism.[90]: 12 [91]: 40–50

Since Albert Schweitzer's book The Quest of the Historical Jesus, scholars have stated that many of the portraits of Jesus are "pale reflections of the researchers" themselves.[19][92][93] Schweitzer stated: "There is no historical task which so reveals a man's true self as the writing of a life of Jesus."[94]: 4 John Dominic Crossan summarized saying, many authors writing about the life of Jesus "do autobiography and call it biography."[19][95]

Scarcity of sources

There is no physical or archaeological evidence for Jesus, and there are no writings by Jesus.[5]: 43 First century Greek and Roman authors do not mention Jesus.[5]: 43 Textual scholar Bart Ehrman writes that it is a myth that the Romans kept detailed records of everything, however, within a century of Jesus' death there are three extant Roman references to Jesus. While none of them were written during Jesus' lifetime, that is not unusual for personages from antiquity. Josephus, the first-century Romano-Jewish scholar, mentions Jesus twice.[5]: 44, 45 . There are enough independent attestations of Jesus' existence, Ehrman says, it is "astounding for an ancient figure of any kind".[96] While there are additional second and third century references to Jesus, evangelical philosopher and historian Gary Habermas says extra-biblical sources are of varied quality and dependability and can only provide a broad outline of the life of Jesus. He also points out that Christian non-New Testament sources, such as the church fathers, rely on the New Testament for much of their data and cannot therefore be considered as independent sources.[97]: 228, 242

The primary sources on Jesus are the Gospels, therefore the Jesus of history is inextricably bound to the issue of the historical reliability of those writings.[98]: 15–23 The authenticity and reliability of the gospels and the letters of the apostles have been questioned, and there are few events mentioned in the gospels that are universally accepted.[99] However, Bart Ehrman says "To dismiss the Gospels from the historical record is neither fair nor scholarly."[5]: 73 [100]: 3–124 [101] He adds: "There is historical information about Jesus in the Gospels."[102]: 14

Myth theory

The Christ myth theory is the proposition that Jesus of Nazareth never existed, or if he did, he had virtually nothing to do with the founding of Christianity and the accounts in the gospels.[103] In the 21st century, there have been a number of books and documentaries on this subject. For example, Earl Doherty has written that Jesus may have been a real person, but that the biblical accounts of him are almost entirely fictional.[104]: 12 [105][106][107] Many proponents use a three-fold argument first developed in the 19th century: that the New Testament has no historical value, that there are no non-Christian references to Jesus Christ from the first century, and that Christianity had pagan and/or mythical roots.[108]

Since the 1970's, various scholars such as Joachim Jeremias, E. P. Sanders and Gerd Thiessen have traced elements of Christianity to diversity in First-century Judaism and discarded nineteenth century views that Jesus was based on previous pagan deities.[109] Mentions of Jesus in extra-biblical texts do exist and are supported as genuine by the majority of historians.[5] Historical scholars see differences between the content of the Jewish Messianic prophecies and the life of Jesus, undermining views Jesus was invented as a Jewish Midrash or Peshar.[110]: 344–351 The presence of details of Jesus' life in Paul, and the differences between letters and Gospels, are sufficient for most scholars to dismiss mythicist claims concerning Paul.[110]: 208–233 [111] New Testament scholar Gerd Theissan says "there is broad scholarly consensus that we can best find access to the historical Jesus through the Synoptic tradition."[53]: 25 And Ehrman adds "To dismiss the Gospels from the historical record is neither fair nor scholarly."[5]: 73 If Jesus did not exist, "the origin of the faith of the early Christians remains a perplexing mystery."[110]: 233 Eddy and Boyd say the best history can assert is probability, yet the probability of Jesus having existed is so high, Ehrman says "virtually all historians and scholars have concluded Jesus did exist as a historical figure."[112]: 12, 21 [113]

Contemporary scholars of antiquity agree that Jesus existed, and biblical scholars and classical historians view the theories of his nonexistence as effectively refuted.[5][7][8][114][115] Historian James Dunn writes: "Today nearly all historians, whether Christians or not, accept that Jesus existed".[116] In a 2011 review of the state of modern scholarship, Bart Ehrman (a secular agnostic) wrote: "He certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees."[102]: 15–22 Robert M. Price (an atheist who denies the existence of Jesus) agrees that this perspective runs against the views of the majority of scholars.[117] Michael Grant (a classicist and historian) states that "In recent years, 'no serious scholar has ventured to postulate the non historicity of Jesus' or at any rate very few, and they have not succeeded in disposing of the much stronger, indeed very abundant, evidence to the contrary."[7] Richard A. Burridge states: "There are those who argue that Jesus is a figment of the Church’s imagination, that there never was a Jesus at all. I have to say that I do not know any respectable critical scholar who says that anymore."[8][110]: 24–26

Historical elements

Existence

There is no indication that writers in antiquity who opposed Christianity questioned the existence of Jesus.[118][119] However, there is widespread disagreement among scholars on the details of the life of Jesus mentioned in the gospel narratives, and on the meaning of his teachings.[12] Scholars differ on the historicity of specific episodes described in the biblical accounts of Jesus,[12] and secular historians tend to begin from the assumption supernatural or miraculous claims about Jesus are questions of faith, rather than historical fact.[120] Underlining these differences, Bible scholar Gerd Theissan writes that there is only limited consensus among contemporary historians on the broad range of issues concerning the life of Jesus.[18] Yet Bible scholars James Beilby and Paul Eddy say there is some: they write that consensus is "elusive but not entirely absent".[91]: 47 The majority agree "Jesus was a first century Jew, who was baptized by John, went about teaching and preaching, had followers, was believed to be a miracle worker and exorcist, went to Jerusalem where there was an "incident", was subsequently arrested, convicted and crucified."[91]: 48–49 [121]

Evidence

Literary criticism has revealed three texts within the New Testament that critics have identified as remnants of oral creeds used by the early church.[122]: 5–10 There is consensus these texts are older than the writings which contain them. Textual indications are that they were received by Paul, recorded by him in his epistles, but not authored by him. They are: 1 Corinthians 15:3-5ff, a primitive narrative outline of the gospel; Philippians 2:6–11, a song of Christ; and Galatians 3:28, a fragment of prayer used at baptism.[110]: 13–33 [123]: 112–123 The majority of scholars, including textual scholar Bart Ehrman, say 1 Corinthians 15:3-5ff, which references the resurrection, is the oldest passage in the New Testament.[124]: 262 [lower-alpha 1] It was probably in use by the early 30s shortly after the accepted time of Jesus' death and demonstrates the appearance of belief in the resurrection very early in Christian history.[126]: 3–124, 319

In addition to biblical sources, there are a number of mentions of Jesus in non-Christian sources that have been used in the historical analyses of the existence of Jesus.[127] Biblical scholar Frederick Fyvie Bruce says the earliest mention of Jesus outside the New Testament occurs around 55 CE from a historian named Thallos. Thallos' history, like the vast majority of ancient literature, has been lost but not before it was quoted by Sextus Julius Africanus (ca.160-ca.240 CE), a Christian writer, in his History of the World (ca.220). This book likewise was lost, but not before one of its citations of Thallos was taken up by the Byzantine historian Georgius Syncellus in his Chronicle (ca.800). There is no means by which certainty can be established concerning this or any of the other lost references, partial references, and questionable references that mention some aspect of Jesus' life or death, but in evaluating evidence, it is appropriate to note they exist.[128]: 29–33 [129]: 20–23

There are two passages in the writings of the Jewish historian Josephus, and one from the Roman historian Tacitus, that are generally considered good evidence.[127][130] Josephus' Antiquities of the Jews, written around 93–94 AD, includes two references to the biblical Jesus Christ in Books 18 and 20. The general scholarly view is that while the longer passage, known as the Testimonium Flavianum, is most likely not authentic in its entirety, it is broadly agreed upon that it originally consisted of an authentic nucleus, which was then subject to Christian interpolation.[131][132] Of the other mention in Josephus, Josephus scholar Louis H. Feldman has stated that "few have doubted the genuineness" of Josephus' reference to Jesus in Antiquities 20, 9, 1 ("the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James"). Paul references meeting and interacting with James, Jesus' brother, and since this agreement between the different sources supports Josephus' statement, the statement is only disputed by a small number of scholars.[133][134][135][136]

Roman historian Tacitus referred to Christus and his execution by Pontius Pilate in his Annals (written c. AD 116), book 15, chapter 44.[137] Robert E. Van Voorst states that the very negative tone of Tacitus' comments on Christians make the passage extremely unlikely to have been forged by a Christian scribe[129] and Boyd and Eddy state that the Tacitus reference is now widely accepted as an independent confirmation of Christ's crucifixion.[138]

Other considerations outside Christendom include the possible mentions of Jesus in the Talmud. The Talmud speaks in some detail of the conduct of criminal cases of Israel whose texts were gathered together from 200–500 CE. Bart Ehrman says this material is too late to be of much use. Ehrman explains that "Jesus is never mentioned in the oldest part of the Talmud, the Mishnah, but appears only in the later commentaries of the Gemara."[102]: 67–69 Jesus is not mentioned by name, but there is a subtle attack on the virgin birth that refers to the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier "Panthera" (Ehrman says, "In Greek the word for virgin is parthenos"), and a reference to Jesus' miracles as "black magic" learned when he lived in Egypt (as a toddler). Ehrman writes that few contemporary scholars treat this as historical.[102]: 67 [139]

There is only one classical writer who refers positively to Jesus and that is Mara bar Serapion, a Syrian Stoic, who wrote a letter to his son who was also named Serapion from a Roman prison. He speaks of Jesus as ‘the wise king’ and compares his death at the hand of the Jews to that of Socrates at the hands of the Athenians. He links the death of the ‘wise king’ to the Jews being driven from their kingdom. He also states that the ‘wise king’ lives on because of the “new laws he laid down.” The dating of the letter is disputed but was probably soon after 73 AD.[140]

Ehrman says, "There is historical information about Jesus in the Gospels."[102]: 14

Historical facts

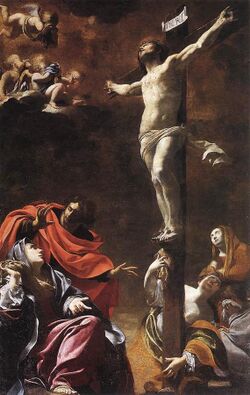

Almost all modern scholars consider his baptism and crucifixion to be historical facts.[9][141]

John P. Meier views the crucifixion of Jesus as historical fact and states that, based on the criterion of embarrassment, Christians would not have invented the painful death of their leader.[142] Meier states that a number of other criteria — the criterion of multiple attestation (i.e., confirmation by more than one source), the criterion of coherence (i.e., that it fits with other historical elements) and the criterion of rejection (i.e., that it is not disputed by ancient sources) — help establish the crucifixion of Jesus as a historical event.[142] Eddy and Boyd state that it is now firmly established that there is non-Christian confirmation of the crucifixion of Jesus – referring to the mentions in Josephus and Tacitus.[138]

Most scholars in the third quest for the historical Jesus consider the crucifixion indisputable,[11][142][143][144] as do Bart Ehrman,[144] John Dominic Crossan[11] and James Dunn.[9] Although scholars agree on the historicity of the crucifixion, they differ on the reason and context for it, e.g. both E. P. Sanders and Paula Fredriksen support the historicity of the crucifixion, but contend that Jesus did not foretell his own crucifixion, and that his prediction of the crucifixion is a Christian story.[145] Geza Vermes also views the crucifixion as a historical event but believes this was due to Jesus’ challenging of Roman authority.[145]

The existence of John the Baptist within the same time frame as Jesus, and his eventual execution by Herod Antipas is attested to by 1st-century historian Josephus and the overwhelming majority of modern scholars view Josephus' accounts of the activities of John the Baptist as authentic.[146][147] One of the arguments in favor of the historicity of the Baptism of Jesus by John is the criterion of embarrassment, i.e. that it is a story which the early Christian Church would have never wanted to invent.[148][149][150] Another argument used in favour of the historicity of the baptism is that multiple accounts refer to it, usually called the criterion of multiple attestation.[151] Technically, multiple attestation does not guarantee authenticity, but only determines antiquity.[152] However, for most scholars, together with the criterion of embarrassment it lends credibility to the baptism of Jesus by John being a historical event.[151][153][154][155]

Other possibly historical elements

In addition to the two historical elements of baptism and crucifixion, scholars attribute varying levels of certainty to various other aspects of the life of Jesus, although there is no universal agreement among scholars on these items.[156] Amy-Jill Levine has stated that "there is a consensus of sorts on the basic outline of Jesus' life. Most scholars agree that Jesus was baptised by John, debated with fellow Jews on how best to live according to God’s will, engaged in healings and exorcisms, taught in parables, gathered male and female followers in Galilee, went to Jerusalem, and was crucified by Roman soldiers during the governorship of Pontius Pilate (26–36 CE)."[157]

In addition, some scholars have proposed additional historical possibilities such as:

- An approximate chronology of Jesus can be estimated from non-Christian sources, and confirmed by correlating them with New Testament accounts.[158][159]

- Jesus was a Galilean Jew who was born between 7 and 2 BC and died 30–36 AD.[158][160][161]

- Jesus lived only in Galilee and Judea,[162][163][164] and never travelled or studied outside Galilee and Judea.[165][166][167]

- Jesus spoke Aramaic and may have also spoken Hebrew and Greek.[168][169][170][171] James D. G. Dunn states that there is "substantial consensus" that Jesus gave his teachings in Aramaic,[172] although the Galilean dialect of Aramaic was clearly distinguishable from the Judean dialect.[173]

- Claims about the appearance or ethnicity of Jesus are mostly subjective, based on cultural stereotypes and societal trends rather than on scientific analysis.[174][175][176]

- The baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist can be dated approximately from Josephus' references (Antiquities 18.5.2) to a date before AD 28–35.[146][177][178][179][180]

- The main topic of his teaching was the Kingdom of God, and he presented this teaching in parables that were surprising and sometimes confounding.[181]

- Jesus taught an ethic of forgiveness, as expressed in aphorisms such as "turn the other cheek" or "go the extra mile."[181]

- Jesus caused a controversy at the Temple.[10][156][182]

- The date of the crucifixion of Jesus was earlier than 36 AD, based on the dates of the prefecture of Pontius Pilate who was governor of Roman Judea from 26 AD until 36 AD.[183][184][185]

Portraits of the historical Jesus

Since the 18th century, three separate scholarly quests for the historical Jesus have taken place, each with distinct characteristics and developing new and different research criteria.[16][17] The portraits of Jesus that have been constructed in these processes have often differed from each other, and from the dogmatic image portrayed in the gospel accounts.[18] These portraits include that of Jesus as an apocalyptic prophet, charismatic healer, Cynic philosopher, Jewish Messiah and prophet of social change,[19][20] but there is little scholarly agreement on a single portrait, or the methods needed to construct it.[18][21][22] There are, however, overlapping attributes among the various portraits, and scholars who differ on some attributes may agree on others.[19][20][23]

Contemporary scholarship, representing the "third quest," places Jesus firmly in the Jewish tradition. Jesus was a Jewish preacher who taught that he was the path to salvation, everlasting life, and the Kingdom of God.[15] A primary criterion used to discern historical details in the "third quest" is that of plausibility, relative to Jesus' Jewish context and to his influence on Christianity. Contemporary scholars of the "third quest" include E. P. Sanders, Geza Vermes, Gerd Theissen, Christoph Burchard, and John Dominic Crossan. The main disagreement in contemporary research is whether Jesus was apocalyptic.[186] In contrast, certain North American scholars, such as Burton Mack, advocate for a non-eschatological Jesus, one who is more of a Cynic sage than an apocalyptic preacher.[187]

"M.Borg and G.Vermes have portrayed Jesus as a charismatic figure who had visionary or mystical experiences of God."[85]: 118 For Crossan, Jesus' agenda was social rather than spiritual.[85]: 118 Albert Schweitzer demonstrated to the world of the early twentieth century that Jesus' was an eschatological preacher who expected the imminent end of all things and died disillusioned.[188]: 173 E. P. Sanders said Jesus was a charismatic and autonomous prophet who acted on his own authority as the founder of a '"renewal movement within Judaism." This scholarship suggests a continuity between Jesus' life as a wandering charismatic and the same lifestyle carried forward by followers after his death..[189]: 238 N. T. Wright says Jesus is "the new Temple at the heart of the new creation."[190]

Ministry

Miracles

The miracles of Jesus are the supernatural[191] deeds attributed to Jesus in Christian and Islamic texts. The majority are faith healing, exorcisms, resurrection of the dead and control over nature.[192][193]

The majority of scholars agree that Jesus was a healer and an exorcist.[194][195] In Mark 3:22, Jesus' opponents accuse him of being possessed by Beelzebul, which they claimed gave him the power to exorcise demons. Extrabiblical sources for Jesus performing miracles include Josephus, Celsus, and the Talmud.[196]

Jesus as divine

The majority of contemporary scholars approach the question of Jesus' divinity by attempting to determine what Jesus might have thought of himself.[197] Many scholars assert there is no evidence indicating Jesus had any divine self-awareness.[198]: 198 Gerald Bray writes that "All we can say for sure about Jesus' early years is that whatever he understood about himself and his future mission, he kept it to himself."[198]: 198

Jesus' public ministry began with baptism by John. The evangelist writes that John proclaims Jesus to be "the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world." Bray says it would be odd for John to know that about Jesus upon meeting him but Jesus not to know it about himself.[198]: 198 It has been argued by some, such as Bart Ehrman, that such statements are later interpolations by the church.[199] However, there is a compelling argument against interpolation since the early credal statements within the Pauline letters indicate the church's belief in a high Christology was very early.[123]: 112–123 There is also a high Christology in the book of John with at least 17 statements (some of which are disputed) claiming divinity.[200]: 4

According to "kenotic Christology," taken from the Greek noun kēnosis for "emptying" in Philippians 2, Jesus surrendered his divinity in order to become a man, which would mean Jesus was not divine while on earth. There are also Jesus' own statements of inferiority to the Father that must be taken into account.[198]: 199–204 Arianism makes Jesus divine but not fully God; the theologian Gerald Bray says such Arianism may be the majority view today in otherwise orthodox Christian organizations that is simply practiced under another name.[198]: 211

The evangelist's stories, that might indicate Jesus' belief in himself as divine, are: the temptations in the desert, the Transfiguration, his ministry of forgiving sins, the miracles, the exorcisms, the last supper, the resurrection, and the post-resurrection appearances.[201] Some scholars argue that Jesus' use of three important terms: Messiah, Son of God, and Son of Man, added to his "I am the..." and his "I have come..." statements, indicate Jesus saw himself in a divine role.[15][197] Bray says Jesus probably did teach his disciples he was the Son of God, because if he had not, no first century monotheistic Jew would have tolerated the suggestion from others.[198]: 198 Jesus also called himself the "Son of Man" tying the term to the eschatological figure in Daniel.[202]: 18–19, 83–176

Messiah

In the Hebrew Bible, three classes of people are identified as "anointed," that is, "Messiahs": prophets, priests, and kings.[197] In Jesus' time, the term Messiah was used in different ways, and no one can be sure how Jesus would even have meant it if he had accepted the term.[197]

The Jews of Jesus' time waited expectantly for a divine redeemer who would restore Israel, which had suffered foreign conquest and occupation for hundreds of years. John the Baptist was apparently waiting for one greater than himself, an apocalyptic figure.[203] Christian scripture and faith acclaim Jesus as this "Messiah" ("anointed one," "Christ").

Son of God

Paul describes God as declaring Jesus to be the Son of God by raising him from the dead, and Sanders argues Mark portrays God as adopting Jesus as his son at his baptism,[197] although many others do not accept this interpretation of Mark.[204] Sanders argues that for Jesus to be hailed as the Son of God does not necessarily mean that he is literally God's offspring.[197] Rather, it indicates a very high designation, one who stands in a special relation to God.[197] Sanders writes that Jesus believed himself to have full authority to speak and to act on God's behalf. Jesus asserted his own authority as something separate from any previously established authority based on his sense of personal connection with the deity.[197]: 238, 239

In the Synoptic Gospels, the being of Jesus as "Son of God" corresponds exactly to the typical Hasidean from Galilee, a "pious" holy man that by God's intervention performs miracles and exorcisms.[205][206]

Son of Man

The most literal translation of Son of Man is "Son of Humanity," or "human being." Jesus uses "Son of Man" to mean sometimes "I" or a mortal in general, sometimes a divine figure destined to suffer, and sometimes a heavenly figure of judgment soon to arrive. Jesus' usage of the term "Son of Man" in the first way is historical but without divine claim. The Son of Man as one destined to suffer seems to be, according to some, a Christian invention that does not go back to Jesus, and it is not clear whether Jesus meant himself when he spoke of the divine judge.[197] These three uses do not appear together, such as the Son of Man who suffers and returns.[197] Others maintain that Jesus' use of this phrase illustrates Jesus' self-understanding as the divine representative of God.[207]

Other depictions

The title Logos, identifying Jesus as the divine word, first appears in the Gospel of John, written c. 90–100.[208]

Raymond E. Brown concluded that the earliest Christians did not call Jesus, "God."[209] Liberal New Testament scholars broadly agreed that Jesus did not make any implicit claims to be God.[210] (See also Divinity of Jesus and Nontrinitarianism) However, quite a number of New Testament scholars today would defend the claim that, historically, Jesus did claim to be divine.[211]

The gospels and Christian tradition depict Jesus as being executed at the insistence of Jewish leaders, who considered his claims to divinity to be blasphemous. (See also Responsibility for the death of Jesus) Fears that enthusiasm over Jesus might lead to Roman intervention is an alternate explanation for his arrest regardless of his preaching. "He was, perhaps, considered a destabilizing factor and removed as a precautionary measure."[15][212]: 879 [213]

Jesus and John the Baptist

Jesus began preaching, teaching, and healing after he was baptized by John the Baptist, an apocalyptic ascetic preacher who called on Jews to repent.

Jesus was apparently a follower of John, a populist and activist prophet who looked forward to divine deliverance of the Jewish homeland from the Romans.[214] John was a major religious figure, whose movement was probably larger than Jesus' own.[215] Herod Antipas had John executed as a threat to his power.[215] In a saying thought to have been originally recorded in Q,[216] the historical Jesus defended John shortly after John's death.[217]

John's followers formed a movement that continued after his death alongside Jesus' own following.[215] Some of Jesus' followers were former followers of John the Baptist.[215] Fasting and baptism, elements of John's preaching, may have entered early Christian practice as John's followers joined the movement.[215]

Crossan portrays Jesus as rejecting John's apocalyptic eschatology in favor of a sapiential eschatology, in which cultural transformation results from humans' own actions, rather than from God's intervention.[218]

Historians consider Jesus' baptism by John to be historical, an event that early Christians would not have included in their gospels in the absence of a "firm report."[219] Like Jesus, John and his execution are mentioned by Josephus.[215]

John the Baptist's prominence in both the gospels and Josephus suggests that he may have been more popular than Jesus in his lifetime; also, Jesus' mission does not begin until after his baptism by John.

Scholars posit that Jesus may have been a direct follower in John the Baptist's movement. Prominent Historical Jesus scholar John Dominic Crossan suggests that John the Baptist may have been killed for political reasons, not necessarily the personal grudge given in Mark's gospel.[220]

Ministry and teachings

The Synoptic Gospels agree that Jesus grew up in Nazareth, went to the River Jordan to meet and be baptised by the prophet John (Yohannan) the Baptist, and shortly after began healing and preaching to villagers and fishermen around the Sea of Galilee (which is actually a freshwater lake). Although there were many Phoenician, Hellenistic, and Roman cities nearby (e.g. Gesara and Gadara; Sidon and Tyre; Sepphoris and Tiberias), there is only one account of Jesus healing someone in the region of the Gadarenes found in the three Synoptic Gospels (the demon called Legion), and another when he healed a Syro-Phoenician girl in the vicinity of Tyre and Sidon.[221] The center of his work was Capernaum, a small town (about 500 by 350 meters, with a population of 1,500–2,000) where, according to the gospels, he appeared at the town's synagogue (a non-sacred meeting house where Jews would often gather on the Sabbath to study the Torah), healed a paralytic, and continued seeking disciples.(Matthew 4:13, 8:5, 11:23, 17:24Luke 4:31–36 and Mark 1:21–28

Once Jesus established a following (although there are debates over the number of followers), he moved towards the Davidic capital of the United Monarchy, the city of Jerusalem.

Length of ministry

Historians do not know how long Jesus preached. The Synoptic Gospels suggest one year, but there is some doubt since they are not written chronologically.[222] The Gospel of John mentions three Passovers,[223] and Jesus' ministry is traditionally said to have been three years long.[224][225] Others claim that Jesus' ministry apparently lasted one year, possibly two.[226]

Parables and paradoxes

Jesus taught in parables and aphorisms. A parable is a figurative image with a single message (sometimes mistaken for an analogy, in which each element has a metaphoric meaning). An aphorism is a short, memorable turn of phrase. In Jesus' case, aphorisms often involve some paradox or reversal. Authentic parables probably include the Good Samaritan and the Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard. Authentic aphorisms include "turn the other cheek," "go the second mile," and "love your enemies."[227][228][229]

Crossan writes that Jesus' parables worked on multiple levels at the same time, provoking discussions with his peasant audience.[218]

Jesus' parables and aphorisms circulated orally among his followers for years before they were written down and later incorporated into the gospels. They represent the earliest Christian traditions about Jesus.[213]

Eschatology

Jesus preached mainly about the Kingdom of God. Scholars are divided over whether he was referring to an imminent apocalyptic event or the transformation of everyday life, or some combination.

Most of the scholars participating in the third quest hold that Jesus believed the end of history was coming within his own lifetime or within the lifetime of his contemporaries.[187][230][231] This view, generally known as "consistent eschatology," was influential during the early to the mid—twentieth century. C. H. Dodd and others have insisted on a "realized eschatology" that says Jesus' own ministry fulfilled prophetic hopes. Many conservative scholars have adopted the paradoxical position the kingdom is both "present" and "still to come" claiming Pauline eschatology as support.[232]: 208–209 R. T. France and N. T. Wright and others have taken Jesus' apocalyptic statements of an imminent end, historically, as referring to the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE.[233]: 143–152

Disputed verses include the following:

- In Mark 9:1 Jesus says "there are some standing here who will not taste death until they see that the Kingdom of God has come in power." New Testament scholar D. C. Allison Jr. writes this verse may be taken to indicate the end was expected soon, but it may also be taken to refer to the Transfiguration, or the resurrection, or the destruction of Jerusalem with no certainty surrounding the issue.[234]: 208–209

- In Luke 21:35–36, Jesus urges constant, unremitting preparedness on the part of his followers. This can be seen in light of the imminence of the end of history and the final intervention of God. "Be alert at all times, praying to have strength to flee from all these things that are about to take place and to stand in the presence of the Son of Man." New Testament scholar Robert H. Stein says "all these things" in Luke 21:36 and in Mark 11:28 and in Mark 13:30 are identical phrases used 26 times in the New Testament; 24 of those all have the antecedent they refer to just before the expression itself. In these passages, that is the destruction of the Temple. "Do you see all these great buildings?” replied Jesus. “Not one stone here will be left on another; every one will be thrown down.”[235]: 68

- In Mark 13:24–27, 30, Jesus describes what will happen when the end comes, saying that "the sun will grow dark and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from heaven, and ... they will see the Son of Man coming on the clouds with great power and glory." He gives a timeline that is shrouded in ambiguity and debate: "Truly I tell you, this generation will not pass away before all these things take place" while in verse 32 it says "but about that day or hour no one knows." Mark 13 contains both imminence and delay throughout (Mark 13:2,29 and 13:24).[236]: 9

- The Apostle Paul might have shared this expectation of an imminent end. Toward the end of 1 Corinthians 7, he counsels the unmarried, writing, "I think that, in view of the impending crisis, it is well for you to remain as you are." "I mean, brothers and sisters, the appointed time has grown short ... For the present form of this world is passing away." (1 Corinthians 7:26, 29, 31) The theologian Geerhardus Vos writes that Paul's eschatology is of that paradoxical strain of the kingdom of God being both present and in the future. Paul repeatedly admonishes his readers to live in the present in total devotion as if every day were the future "last days" come to pass.[237]: preface

According to Vermes, Jesus' announcement of the imminent arrival of the Kingdom of God "was patently not fulfilled" and "created a serious embarrassment for the primitive church."[238] According to Sanders, these eschatological sayings of Jesus are "passages that many Christian scholars would like to see vanish" as "the events they predict did not come to pass, which means that Jesus was wrong."[189]: 178

Robert W. Funk and colleagues, on the other hand, wrote that beginning in the 1970s, some scholars have come to reject the view of Jesus as eschatological, pointing out that he rejected the asceticism of John the Baptist and his eschatological message. In this view, the Kingdom of God is not a future state, but rather a contemporary, mysterious presence. Crossan describes Jesus' eschatology as based on establishing a new, holy way of life rather than on God's redeeming intervention in history.[218]

Evidence for the Kingdom of God as already present derives from these verses.[239]

- In Luke 17:20–21, Jesus says that one will not be able to observe God's Kingdom arriving, and that it "is right there in your presence."

- In Thomas 113, Jesus says that God's Kingdom "is spread out upon the earth, and people don't see it."

- In Luke 11:20, Jesus says that if he drives out demons by God's finger then "for you" the Kingdom of God has arrived.

- Furthermore, the major parables of Jesus do not reflect an apocalyptic view of history.

The Jesus Seminar concludes that apocalyptic statements attributed to Jesus could have originated from early Christians, as apocalyptic ideas were common, but the statements about God's Kingdom being mysteriously present cut against the common view and could have originated only with Jesus himself.[239]

Laconic sage

The sage of the ancient Near East was a self-effacing man of few words who did not provoke encounters.[181] A holy man offers cures and exorcisms only when petitioned, and even then may be reluctant.[181] Jesus seems to have displayed a similar style.[181]

The gospels present Jesus engaging in frequent "question and answer" religious debates with Pharisees and Sadducees. The Jesus Seminar believes the debates about scripture and doctrine are rabbinic in style and not characteristic of Jesus.[240] They believe these "conflict stories" represent the conflicts between the early Christian community and those around them: the Pharisees, Sadducees, etc. The group believes these sometimes include genuine sayings or concepts but are largely the product of the early Christian community.

Table fellowship

Open table fellowship with outsiders was central to Jesus' ministry.[218] His practice of eating with the lowly people that he healed defied the expectations of traditional Jewish society.[218] He presumably taught at the meal, as would be expected in a symposium.[213] His conduct caused enough of a scandal that he was accused of being a glutton and a drunk.[213]

Crossan identifies this table practice as part of Jesus' radical egalitarian program.[218] The importance of table fellowship is seen in the prevalence of meal scenes in early Christian art[218] and in the Eucharist, the Christian ritual of bread and wine.[213]

Disciples

Jesus recruited twelve Galilean peasants as his inner circle, including several fishermen.[241] The fishermen in question and the tax collector Matthew would have business dealings requiring some knowledge of Greek.[242] The father of two of the fishermen is represented as having the means to hire labourers for his fishing business, and tax collectors were seen as exploiters.[243] The twelve were expected to rule the twelve tribes of Israel in the Kingdom of God.[241]

The disciples of Jesus play a large role in the search for the historical Jesus. However, the four gospels use different words to apply to Jesus' followers. The Greek word ochloi refers to the crowds who gathered around Jesus as he preached. The word mathetes refers to the followers who remained for more teaching. The word apostolos refers to the twelve disciples, or apostles, whom Jesus chose specifically to be his close followers. With these three categories of followers, John P. Meier uses a model of concentric circles around Jesus, with an inner circle of true disciples, a larger circle of followers, and an even larger circle of those who gathered to listen to him.

Jesus controversially accepted women and sinners (those who violated purity laws) among his followers. Even though women were never directly called "disciples," certain passages in the gospels seem to indicate that women followers of Jesus were equivalent to the disciples. It was possible for members of the ochloi to cross over into the mathetes category. However, Meier argues that some people from the mathetes category actually crossed into the apostolos category, namely Mary Magdalene. The narration of Jesus' death and the events that accompany it mention the presence of women. Meier states that the pivotal role of the women at the cross is revealed in the subsequent narrative, where at least some of the women, notably Mary Magdalene, witnessed both the burial of Jesus (Mark 15:47) and discovered the empty tomb (Mark 16:1–8). Luke also mentions that as Jesus and the Twelve were travelling from city to city preaching the "good news," they were accompanied by women, who provided for them out of their own means. We can conclude that women did follow Jesus a considerable length of time during his Galilean ministry and his last journey to Jerusalem. Such a devoted, long-term following could not occur without the initiative or active acceptance of the women who followed him. In name, the women are not historically considered "disciples" of Jesus, but the fact that he allowed them to follow and serve him proves that they were to some extent treated as disciples.

The gospels recount Jesus commissioning disciples to spread the word, sometimes during his life (e.g., Mark 6:7–12) and sometimes during a resurrection appearance (e.g., Matthew 28:18–20). These accounts reflect early Christian practice as well as Jesus' original instructions, though some scholars contend that the historical Jesus issued no such missionary commission.[244]

According to John Dominic Crossan, Jesus sent his disciples out to heal and to proclaim the Kingdom of God. They were to eat with those they healed rather than with higher status people who might well be honored to host a healer, and Jesus directed them to eat whatever was offered them. This implicit challenge to the social hierarchy was part of Jesus' program of radical egalitarianism. These themes of healing and eating are common in early Christian art.[218]

Jesus' instructions to the missionaries appear in the Synoptic Gospels and in the Gospel of Thomas.[218] These instructions are distinct from the commission that the resurrected Jesus gives to his followers, the Great Commission, text rated as black (inauthentic) by the Jesus Seminar.[245]

Asceticism

The fellows of the Jesus Seminar mostly held that Jesus was not an ascetic, and that he probably drank wine and did not fast, other than as all observant Jews did.[246] He did, however, promote a simple life and the renunciation of wealth.

Jesus said that some made themselves "eunuchs" for the Kingdom of Heaven (Matthew 19:12). This aphorism might have been meant to establish solidarity with eunuchs, who were considered "incomplete" in Jewish society.[247] Alternatively, he may have been promoting celibacy.

Some[who?] suggest that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene, or that he probably had a special relationship with her.[248] However, Ehrman notes the conjectural nature of these claims as "not a single one of our ancient sources indicates that Jesus was married, let alone married to Mary Magdalene."[249]

John the Baptist was an ascetic and perhaps a Nazirite, who promoted celibacy like the Essenes.[250] Ascetic elements, such as fasting, appeared in Early Christianity and are mentioned by Matthew during Jesus' discourse on ostentation. It has been suggested that James, the brother of Jesus and leader of the Jerusalem community till 62, was a Nazirite.[251]

Jerusalem

Jesus and his followers left Galilee and traveled to Jerusalem in Judea. They may have traveled through Samaria as reported in John, or around the border of Samaria as reported in Luke, as was common practice for Jews avoiding hostile Samaritans. Jerusalem was packed with Jews who had come for Passover, perhaps comprising 300,000 to 400,000 pilgrims.[252]

Entrance to Jerusalem

Jesus might have entered Jerusalem on a donkey as a symbolic act, possibly to contrast with the triumphant entry that a Roman conqueror would make, or to enact a prophecy in Zechariah. Christian scripture makes the reference to Zechariah explicit, perhaps because the scene was invented as scribes looked to scripture to help them flesh out the details of the gospel narratives.[213]

Temple disturbance

According to the gospel accounts Jesus taught in Jerusalem, and he caused a disturbance at the Temple.[213] In response, the temple authorities arrested him and turned him over to the Roman authorities for execution.[213] He might have been betrayed into the hands of the temple police, but Funk suggests the authorities might have arrested him with no need for a traitor.[213]

Crucifixion

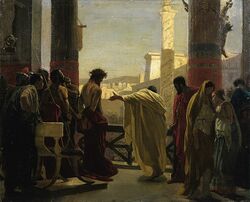

Jesus was crucified by Pontius Pilate, the Prefect of Iudaea province (26 to 36 AD). Some scholars suggest that Pilate executed Jesus as a public nuisance, perhaps with the cooperation of the Jewish authorities.[213] Jesus' cleansing of the Temple may well have seriously offended his Jewish audience, leading to his death;[253][254][255] while Bart D. Ehrman argued that Jesus' actions would have been considered treasonous and thus a capital offense by the Romans.[256] The claim that the Sadducee high-priestly leaders and their associates handed Jesus over to the Romans is strongly attested.[212] Historians debate whether Jesus intended to be crucified.[257]

The Jesus Seminar argued that Christian scribes seem to have drawn on scripture in order to flesh out the passion narrative, such as inventing Jesus' trial.[213] However, scholars are split on the historicity of the underlying events.[258]

John Dominic Crossan points to the use of the word "kingdom" in his central teachings of the "Kingdom of God," which alone would have brought Jesus to the attention of Roman authority. Rome dealt with Jesus as it commonly did with essentially non-violent dissension: the killing of its leader. It was usually violent uprisings such as those during the Roman–Jewish Wars that warranted the slaughter of leader and followers. The fact that the Romans thought removing the head of the Christian movement was enough suggests that the disciples were not organised for violent resistance, and that Jesus' crucifixion was considered a largely preventative measure. As the balance shifted in the early Church from the Jewish community to Gentile converts, it may have sought to distance itself from rebellious Jews (those who rose up against the Roman occupation). There was also a schism developing within the Jewish community as these believers in Jesus were pushed out of the synagogues after the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE (see Council of Jamnia). The divergent accounts of Jewish involvement in the trial of Jesus suggest some of the unfavorable sentiments between such Jews that resulted. See also List of events in early Christianity.

Aside from the fact that the gospels provide different accounts of the Jewish role in Jesus's death (for example, Mark and Matthew report two separate trials, Luke one, and John none), Fredriksen, like other scholars (see Catchpole 1971) argues that many elements of the gospel accounts could not possibly have happened: according to Jewish law, the court could not meet at night; it could not meet on a major holiday; Jesus's statements to the Sanhedrin or the High Priest (e.g. that he was the messiah) did not constitute blasphemy; the charges that the gospels purport the Jews to have made against Jesus were not capital crimes against Jewish law; even if Jesus had been accused and found guilty of a capital offense by the Sanhedrin, the punishment would have been death by stoning (the fates of Saint Stephen and James the Just for example) and not crucifixion. This necessarily assumes that the Jewish leaders were scrupulously obedient to Roman law, and never broke their own laws, customs or traditions even for their own advantage. In response, it has been argued that the legal circumstances surrounding the trial have not been well understood,[259] and that Jewish leaders were not always strictly obedient, either to Roman law or to their own.[260] Furthermore, talk of a restoration of the Jewish monarchy was seditious under Roman occupation. Further, Jesus would have entered Jerusalem at an especially risky time, during Passover, when popular emotions were running high. Although most Jews did not have the means to travel to Jerusalem for every holiday, virtually all tried to comply with these laws as best they could. And during these festivals, such as the Passover, the population of Jerusalem would swell, and outbreaks of violence were common. Scholars suggest that the High Priest feared that Jesus' talk of an imminent restoration of an independent Jewish state might spark a riot. Maintaining the peace was one of the primary jobs of the Roman-appointed High Priest, who was personally responsible to them for any major outbreak. Scholars therefore argue that he would have arrested Jesus for promoting sedition and rebellion, and turned him over to the Romans for punishment.

Both the gospel accounts and [the] Pauline interpolation [found at 1 Thes 2:14–16] were composed in the interval immediately following the terrible war of 66–73. The Church had every reason to assure prospective Gentile audiences that the Christian movement neither threatened nor challenged imperial sovereignty, despite the fact that their founder had himself been crucified, that is, executed as a rebel.[261]

However, Paul's preaching of the gospel and its radical social practices were by their very definition a direct affront to the social hierarchy of Greco-Roman society itself, and thus these new teachings undermined the Empire, ultimately leading to full-scale Roman persecution of Christians aimed at stamping out the new faith.

Burial and Empty Tomb

Craig A. Evans contends that, "the literary, historical and archaeological evidence points in one direction: that the body of Jesus was placed in a tomb, according to Jewish custom."[262]

John Dominic Crossan, based on his unique position that the Gospel of Peter contains the oldest primary source about Jesus, argued that the burial accounts become progressively extravagant and thus found it historically unlikely that an enemy would release a corpse, contending that Jesus' followers did not have the means to know what happened to Jesus' body.[263] Crossan's position on the Gospel of Peter has not found scholarly support,[264] from Meyer's description of it as "eccentric and implausible,"[265] to Koester's critique of it as "seriously flawed."[266] Habermas argued against Crossan, stating that the response of Jewish authorities against Christian claims for the resurrection presupposed a burial and empty tomb,[267] and he observed the discovery of the body of Yohanan Ben Ha'galgol, a man who died by crucifixion in the first century and was discovered at a burial site outside ancient Jerusalem in an ossuary, arguing that this find revealed important facts about crucifixion and burial in first century Palestine.[268]

Other scholars consider the burial by Joseph of Arimathea found in Mark 15 to be historically probable,[269] and some have gone on to argue that the tomb was thereafter discovered empty.[270] More positively, Mark Waterman maintains the Empty Tomb priority over the Appearances.[271] Michael Grant wrote:

[I]f we apply the same sort of criteria that we would apply to any other ancient literary sources, then the evidence is firm and plausible enough to necessitate the conclusion that the tomb was indeed found empty.[272]

However, Marcus Borg notes:

the first reference to the empty tomb story is rather odd: Mark, writing around 70 CE, tells us that some women found the tomb empty but told no one about it. Some scholars think this indicates that the story of the empty tomb is a late development and that the way Mark tells it explains why it was not widely (or previously) known[273]

Scholars Gerd Theissen and Annette Merz conclude that "the empty tomb can only be illuminated by the Easter faith (which is based on appearances); the Easter faith cannot be illuminated by the empty tomb."[274]

Ancient historian Gaetano De Sanctis and legal historian Leopold Wenger, writing in the early 20th century, stated that the empty tomb of Jesus was historically real because of evidence from the Nazareth Inscription.[275]

Resurrection appearances

Paul, Mary Magdalene, the Apostles, and others believed they had seen the risen Jesus. Paul recorded his experience in an epistle and lists other reported appearances. The original Mark reports Jesus' empty tomb, and the later gospels and later endings to Mark narrate various resurrection appearances.

Scholars have put forth a number of theories concerning the resurrection appearances of Jesus. Christian scholars such as Dale Allison, William Lane Craig, Gary Habermas, and N. T. Wright conclude that Jesus did in fact rise from the dead.[276] The Jesus Seminar concludes: "In the view of the Seminar, he did not rise bodily from the dead; the resurrection is based instead on visionary experiences of Peter, Paul, and Mary [Magdalene]."[277] E.P. Sanders argues for the difficulty of accusing the early witnesses of any deliberate fraud:

It is difficult to accuse these sources, or the first believers, of deliberate fraud. A plot to foster belief in the Resurrection would probably have resulted in a more consistent story. Instead, there seems to have been a competition: 'I saw him,' 'so did I,' 'the women saw him first,' 'no, I did; they didn't see him at all,' and so on. Moreover, some of the witnesses of the Resurrection would give their lives for their belief. This also makes fraud unlikely.[278]

Most Post-Enlightenment historians[279] believe supernatural events cannot be reconstructed using empirical methods, and thus consider the resurrection a non-historical question but instead a philosophical or theological question.[101]

See also

- Biblical archaeology

- Biblical manuscript

- Census of Quirinius, a census of Judaea taken by Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, Roman governor of Syria, upon the imposition of direct Roman rule in 6 AD.

- Criterion of dissimilarity

- Criticism of the Bible

- Gospel harmony

- Historical background of the New Testament

- Historicity of the Bible

- Jesus in comparative mythology

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Mental health of Jesus

- New Testament places associated with Jesus

- Race and appearance of Jesus

- Timeline of Christianity

- The World's Sixteen Crucified Saviors

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ For example, The Oxford Companion to the Bible, 1993, p.647; Gerd Lüdemann in the Resurrection of Jesus, 1994, pp.171–172; Robert Funk with Roy Hoover in The Acts of Jesus, p.466; James Dunn in Jesus Remembered, 2003, pp.854–855; Michael Goulder in the Baseless Fabric of a Vision, 1996, p.48 agree on the dating.[125]

- Citations

- ↑ Frank Leslie Cross; Elizabeth A. Livingstone (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. pp. 779–. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=fUqcAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA779.

- ↑ Amy-Jill Levine in The Historical Jesus in Context edited by Amy-Jill Levine et al. 2006 Princeton Univ Press ISBN 978-0-691-00992-6 pp. 1–2

- ↑ Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium by Bart D. Ehrman (Sep 23, 1999) ISBN 0195124731 Oxford University Press pp. ix–xi

- ↑ Ehrman, Bart. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-515462-2, chapters 13, 15

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 In a 2011 review of the state of modern scholarship, Bart Ehrman (a secular agnostic) wrote: "He certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees" B. Ehrman, 2011 Forged : writing in the name of God ISBN 978-0-06-207863-6. p. 285

- ↑ Robert M. Price (an atheist who denies the existence of Jesus) agrees that this perspective runs against the views of the majority of scholars: Robert M. Price "Jesus at the Vanishing Point" in The Historical Jesus: Five Views edited by James K. Beilby & Paul Rhodes Eddy, 2009 InterVarsity, ISBN 028106329X p. 61

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Michael Grant (a classicist) states that "In recent years, 'no serious scholar has ventured to postulate the non historicity of Jesus' or at any rate very few, and they have not succeeded in disposing of the much stronger, indeed very abundant, evidence to the contrary." in Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels by Michael Grant 2004 ISBN 1898799881 p. 200

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Richard A. Burridge states: "There are those who argue that Jesus is a figment of the Church’s imagination, that there never was a Jesus at all. I have to say that I do not know any respectable critical scholar who says that anymore." in Jesus Now and Then by Richard A. Burridge and Graham Gould (Apr 1, 2004) ISBN 0802809774 p. 34

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Jesus Remembered by James D. G. Dunn 2003 ISBN 0-8028-3931-2 p, 339 states of baptism and crucifixion that these "two facts in the life of Jesus command almost universal assent".

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Prophet and Teacher: An Introduction to the Historical Jesus by William R. Herzog (4 Jul 2005) ISBN 0664225284 pp. 1–6

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Crossan, John Dominic (1995). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. HarperOne. p. 145. ISBN 0-06-061662-8. "That he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be, since both Josephus and Tacitus ... agree with the Christian accounts on at least that basic fact."

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee by Mark Allan Powell 1998 ISBN 0-664-25703-8 pp. 168–173

- ↑ Sanders, E. P. The historical figure of Jesus. Penguin, 1993.

- ↑ John Dickson, Jesus: A Short Life. Lion Hudson 2009, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Fortress Press. 1998. translated from German (1996 edition)