Religion:Numbers 31

Template:Infobox bible chapter

Numbers 31 is the 31st chapter of the Book of Numbers, the fourth book of the Pentateuch or Torah, the central part of the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament, a sacred text in Judaism and Christianity. Scholars such as Israel Knohl and Dennis T. Olson name this chapter the War against the Midianites.[1][2]

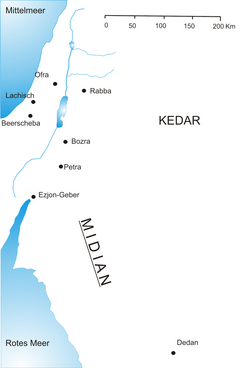

Numbers 31, set in the southern Transjordanian regions of Moab and Midian, narrates how an army of Israelite soldiers commanded by Phinehas (commissioned by Moses and Phinehas' father Eleazar) waged a war against the Midianites, killing all men and boys including their five kings, and taking all livestock, women and girls captive. Moses instructed the soldiers to kill all women who had ever had sex with a man, and to keep the women and girls who were still virgins for themselves. The spoils of war were then divided between the Israelite civilians, soldiers and the god Yahweh.[3][note 1]

Much scholarly and religious controversy exists surrounding the authorship, meaning and morality of this chapter of Numbers.[3] It is closely connected to Numbers 25.[4]: 69

Authorship

The majority of modern biblical scholars believe that the Torah (the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, written in Classical Hebrew) reached its present form in the post-Exilic period (i.e., after c.520 BCE), based on pre-existing written and oral traditions, as well as contemporary geographical and political realities.[5][6][7] Numbers is a Priestly redaction (i.e., editing) of a non-Priestly original.[8]

Scholars generally recognise that mentions of the Midianites in chapters Numbers 22–24 are secondary Priestly (P) additions.[3] They also generally agree that Numbers 25:1–5 contains an earlier version of the story involving the women of Moab, for which the Israelite chiefs are punished by the judges. This earlier version was later augmented by the account in Numbers 25:6–18 with the Midianite women and Phinehas' priesthood as their new focus, perhaps using elements from Psalm 106:28–31 to work with.[2]: 155 These additions, as well as the mention of a Midianite in chapter 25 in a story about the Moabites, may have been an attempt by a later editor to create a connection between Moab and Midian.[3] Martin Noth argued that the author of chapter 31 was probably aware of the combined non-P/P(H) text (with the Moabite–Midianite connection) in chapter 25, and probably knew the entire composite Pentateuch, therefore Numbers 31 was written in whole or in part by an author writing later than regular P.[3] Israel Knohl (1995) argued Numbers 31 was in fact part of the Holiness code (H), which was later added to the Priestly source.[1][3] He pointed to similarities in content, such as the focus on purification in Numbers 5:1–4, chapter 19 and 31:19–24, as well as in linguistics in Numbers 10:9, 27:17, 31:6,19 and Exodus 40:15, all of which had been previously identified with the Holiness School (HS) by other scholars.[1] Some linguistic and theological features also distinguish Numbers 31 from the Priestly Torah (PT) text, such as the wrath of God, which is mentioned several times by HS but never by PT.[1] Some scholars think that the added text was written at a time when the priestly line of Phinehas' descendants was being challenged.[2]: 155

Background

- Israelite–Moabite fraternisation at Peor (Numbers 25:1–5)

The Book of Numbers traces the origins of this Israelite–Midianite conflict to chapters 22 to 25.[3] The Israelites, travelling from Egypt and encamping on the eastern bank of the Jordan River across from Jericho, were on the brink of war with the Moabites (not Midianites). The Moabite king Balak hired the sorcerer Balaam to curse the Israelite soldiers from the peak of Mount Peor, but the Israelite god Yahweh forced him to instead bless the Israelites encamped at Shittim, which he did (Numbers 22–24).[3] Next, Israelite men are said to fraternise with Moabite women by having sex with them and worshipping their gods, including Baal (Numbers 25:1–3).[3] This angered Yahweh, and he instructed Moses to massacre all Israelite men who had done this; Moses passed on these instructions to the judges of Israel (Numbers 25:3–5).[3] It is not narrated whether the instructions were carried out.[2]: 155

- Plague inside the Israelite camp (Numbers 25:6–18)

In verse 6, the narrative suddenly shifts[3] when the Israelite man Zimri brings the Midianite woman Kozbi (daughter of Midianite king Zur) to the Israelite camp, after which a plague is said to have hit the Israelites that left 24,000 dead. Phinehas killed Zimri and Kozbi, ending the plague. Yahweh claimed that Kozbi brought this plague upon the Israelites and told them to "treat the Midianites as enemies and kill them".[9]

- Interlude (Numbers 26–30)

The next four chapters say nothing about the Incident at Peor, except that the plague had passed (verse 1). Yahweh instructed Moses and his priest Eleazar to take a census amongst the Israelites (Numbers 26), settled an inheritance dispute and the future succession of Moses by Joshua (Numbers 27), instructed the Israelites how to conduct certain sacrifices and festivals (Numbers 28–29), and regulated vows between men and women, and fathers and daughters (Numbers 30).[1][3]

Narrative

- Preparations (verses 1–6)

In verses 1 and 2, Yahweh reminded Moses to take revenge on the Midianites as instructed in Numbers 25:16–18, as his last act before his death.[1][3] Accordingly, Moses instructed a thousand men of each of the Twelve Tribes of Israel – 12,000 in total, under Phinehas' leadership – to attack Midian.[2]

- War (7–13)

The Israelite soldiers are narrated to have killed all Midianite men, including the five kings, as well as the sorcerer Balaam.[2] According to verse 49, the Israelites themselves suffered zero casualties.[2] All Midianite towns and camps were burnt;[9] all Midianite women, children and livestock were deported as captives[2] to the "camp on the plains of Moab, by the Jordan across from Jericho", where Moses and Eleazar received them.[2]

- Killing of captive children and non-virgin women (14–18)

Moses was angry that the soldiers had left all women alive, saying: "They were the ones who followed Balaam's advice and enticed the Israelites to be unfaithful to Yahweh in the Peor incident, so a plague struck Yahweh's people. Now kill all the boys. And kill every woman who has slept with a man, but save for yourselves every girl who has never slept with a man."[10][9]

- Ritual purification (19–24)

Next, Moses and Eleazar instructed the soldiers to ritually cleanse and purify themselves and all metal objects they had over a period of seven days.[1][3]

- Division of spoils of war (25–54)

The plunder from the Midianite campaign was "675,000 sheep, 72,000 cattle, 61,000 donkeys and 32,000 women who had never slept with a man."[2] Yahweh instructed Moses and Eleazar to divide these spoils according to a 1:1 ratio between the Israelite soldiers on the one hand, and the Israelite civilians on the other. Yahweh demanded a 0.2% share of the soldiers' half of the spoils for himself; this tribute would be given to him via the Levites, who were responsible for the care of Yahweh's tabernacle. Some of the Midianite golden jewellery plundered during the war (combined weight: about 190 kilograms[10]) was also offered as a gift to Yahweh "to make atonement for ourselves before Yahweh".[10][2]

Interpretation

Historicity and theology

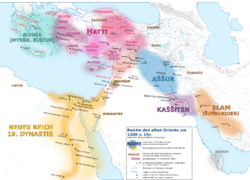

The scholarly consensus is that this war did not take place, certainly not as narrated.[2][4]: 66 Within the wider context of the Exodus, there probably never was an invasion of Canaan (the "Promised Land") by all Israelites escaping from slavery in Egypt.[11] Scholars such as Mark S. Smith assert that Israelite culture emerged from the wider Canaanite culture surrounding it, with whom it had strong linguistic, religious and other cultural links.[12] There was no political unification of several Semitic Canaanite tribes into a single Israelite state until after 1100 BCE.[11] Although some Egyptologists such as Redford (1997), Na'aman (2011) and Bietak (2015) have argued that some Canaanites (referred to by Bietak as "Proto-Israelites") may have been deported to Egypt during the Nineteenth Dynasty's occupation and rule over Canaan under pharaoh Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BCE), they say there is no indication that this included all so-called "Proto-Israelites", most of whom would have experienced Egyptian rule inside Canaan itself in the late 13th century BCE.[13] Na'aman argued that the existing narrative in the collective Hebrew memory of Egyptian rule "was remodeled according to the realities of the late eighth and seventh centuries in Canaan, integrating the experience with the Assyrian oppression and deportations."[13]: 18 The modern scholarly consensus is that the biblical person of Moses is largely a mythical figure while also holding that "a Moses-like figure may have existed somewhere in the southern Transjordan in the mid-late 13th century B.C." and that archaeology is unable to confirm either way.[14][15]

The narrative of Numbers 31 specifically is one out of many in the Hebrew Bible seeking to establish the Israelites as the chosen people of the god Yahweh, who blessed them with victory in battle, health and prosperity, as long as they were faithful to his commands.[2] This second generation of Israelites suffered not a single casualty throughout Numbers 26–36, while the first generation suffered much death in the wilderness (chapters 13–14, 25).[2][note 2] The claims that 12,000 Israelite soldiers exterminated or captured the entire Midianite population and destroyed all their towns without suffering a single casualty are held to be historically impossible, and should be understood as symbolic.[2] Moreover, even other biblical books set in later times still refer to the Midianites as an independent people, such as Judges chapters 6–8, where Gideon fights them.[2] Most likely, the author(s) wished to convey a certain theological message about who Yahweh, Moses, Eleazar and Phinehas were, and how powerful the Israelites would be if Yahweh was on their side.[2]

Olson (2012) noted that the name Kozbi comes from the three Hebrew consonants kzb, meaning "to lie, deceive"; the idea that Kozbi deceived the Israelites is emphasised in verse 25:18: "[The Midianites] deceived (or: 'harassed, assaulted, vexed'; נִכְּל֥וּ nikkəlū) you with their tricks (בְּנִכְלֵיהֶ֛ם bəniḵlêhem) in the matter of Peor and in the matter of Kozbi, the daughter of a Midianite leader, the woman who was killed when the plague came as a result of that incident."[2][17] This suggests she was not a historical character, but invented as a metaphor for danger to the Israelites.[2]

Brown (2015) described how the structure of Numbers 31 showed a pattern of 'command, obedience, extension, purification, command, obedience, extension.' Yahweh commands the Israelites through Moses to execute vengeance and divide the spoils, the Israelite soldiers obey, then do more than Yahweh commanded (extension); the purification is the only action that happens only once and functions as a bridge between the two series.[4] Both Olson and Brown noted that Moses is portrayed as remarkably passive in chapter 25 and, as he was failing to solve the problem, Phinehas had to intervene and take the initiative to slay Kozbi and Zimri, was granted the eternal priesthood and later allowed to lead the Israelites against Midian.[2]: 155 [4]: 70 Brown added that chapter 27 further undermined the political position of an increasingly disobedient Moses in favour of the priesthood, with Yahweh revealing Moses' time is up and he will soon die.[4]: 70–71 This supports the view that the added text was written at a time when the priestly line of Phinehas' descendants was being challenged, as it bolsters their legitimacy as the priestly successors of Moses.[2]: 155

Motive

Scholars disagree about the exact motive Yahweh is claimed to have had in ordering Moses to wage the War against the Midianites. Evidently, something that the Israelite man Zimri and especially the Midianite princess Kozbi did was at the root of the conflict, though what offence they allegedly committed is a source of scholarly confusion. It's not clear from chapter 25 alone whether Kozbi – as a Midianite – had anything to do with the Moabites, nor whether she had sex with Zimri, nor whether he had started worshipping other gods because of her, as other Israelite men had with Moabite women according to verse 25:1. Nor is it clear whether she spread an existing plague to the Israelites, or that Yahweh cursed them with a new plague as a punishment for Zimri fraternising with Kozbi, or violating the sanctity of the Tabernacle.[3]

Questions surrounding the Balaam/Moabite connection

After the Israelite victory over the Midianites six chapters later, Moses is said to have made the following connection: "[The Midianite women] were the ones who followed Balaam's advice and enticed the Israelites to be unfaithful to Yahweh in the Peor incident, so that a plague struck Yahweh's people."[10] This contradicts verses 25:1–3, which states the women were Moabites,[note 4] and verses 25:16–18, in which Yahweh himself claimed that the plague did not hit the Israelite camp until the Midianite princess Kozbi entered it (without reference to sex or foreign gods worship), leading Yahweh to instruct Moses to kill the Midianites, not the Moabites.[note 5] The fact that the Moabites and Midianites are equated as having committed the same offences, and Moses blames Balaam (a Moabite) for whatever the Midianite women (or rather, a single Midianite woman, who had already been slain) did, has puzzled scholars.[3] Knohl (1995) argued that the original non-P text (preserved in 25:1–5) had Moabite women as the main characters, but the H editor (seeking to legitimise Phinehas and his descendants' claims to the priesthood) replaced them with Midianite women in a sloppy manner so that the resulting new text (25:6–18 and all of chapter 31) confused the two tribes.[1] Olson (2012) agreed, writing: "Some of these disjunctions within the narrative may have resulted from the combining of earlier and later traditions into one story."[2]: 155 Ellicott (1897), however, proposed that Balaam entered into Midianite service after being dismissed by the Moabite king Balak.[19] Barnes likewise suggests that the Peor incident was directly perpetrated by the Midianites.[20] To explain this, Benson argues that the Moabites were only mentioned in relation to the incident in Numbers 25:1 because they ultimately initiated the incident or were close courtiers of Balak.[21] Poole on the other hand affirms the connection between the Midianites and Moabites but argues that the Moabites were spared due to being descendants of Lot. Alternatively, he argues that the Midianites sinned more egregiously than the Moabites in the Peor incident, thus warranting their extermination. [22]

Foreign idolatry hypothesis

Hamilton (2005) concluded that Yahweh commanded holy war against Midian "in retaliation for the latter's seduction of Israel into acts of harlotry and idolatry".[23] Olson (2012) stated: "The inclusion of the women of Midian in enticing the Israelites into the worship of an alien god became the reason that justified the later assault against Midian in Numbers 31."[2]: 155 He also pointed to Psalm 106:28–31,[2]: 155 which claims that the plague broke out due to Yahweh being angry at the Israelites for "eating sacrifices offered to lifeless gods" at Peor.[24] Finally, Olson argued that Moses' apparent failure to punish the idolaters (25:4–5) is what motivated Phinehas to take matters into his own hands by killing Zimri and Kozbi.[2]: 155 Brown (2015) stated: "In Num 31:16, Moses justifies his command by appealing to the Midianites' role in the apostasy and plague recounted in Numbers 25, and commentators have generally accepted that explanation and concluded that the text portrays the utter destruction of Midian as the fulfillment of YHWH's call for "vengeance"."[4]: 66

Sexual transgression hypothesis

Some commentators concluded that motive for the War against the Midianites was that Zimri and Kozbi had illicit sex, with Keil and Delitzsch (1870) writing: "[Zimri brought Kozbi] into the camp of the Israelites, before the eyes of Moses and all the congregation, to commit adultery with her in his tent".[25] Jamieson-Fausset-Brown (1871) as well as Keil and Delitzsch (1870) suggested that the Midianites had instigated the Moabite women to seduce the Israelite men (verses 1 and 2), and so only the Midianites were to atone for the 'wickedness' which 'violated the divinity and honour' of Yahweh, not the Moabites.[19] Jamieson-Fausset-Brown added that Yahweh wanted to spare the Moabites because they were the descendants of Lot[note 6] (Deuteronomy 2:9).[19] Hamilton (2005) concluded that Yahweh commanded holy war against Midian "in retaliation for the latter's seduction of Israel into acts of harlotry and idolatry".[23]

Tabernacle desecration hypothesis

Shectman (2009) argued that Zimri and Kozbi were not guilty of sexual transgressions at all; sex with a foreigner is never even considered a capital offence by the Holiness code (H).[3] Rather, they had come too close to the holy Tabernacle, also called the 'Tent of the Congregation'.[3] She based this on the verb used for encroachment, which has the connotation of 'close proximity' and 'violation of priestly authority'.[3] In several other places in the Book of Numbers (e.g. 18:5–7), the stated punishment for encroachment on certain parts of the Tabernacle by non-Israelites or non-Levite Israelites is death.[3] Shectman also noted that Numbers 8:19 claimed that a "plague will strike the Israelites when they go near the sanctuary",[26] and in Numbers 16:42–50[27] (or Numbers 17:7–15 in some Bible editions[28]), this actually happened and 14,700 Israelites died of a plague before Aaron stopped it by making an incense offering to Yahweh.[3] In an incident soon after (Numbers 17:10–13[29] or Numbers 17:25–28[28]), the Israelites panicked when Moses entered the Tabernacle, fearing they were all going to die.[3] She concluded that Numbers 25:6–18 served three purposes: illustrating the encroachment law, legitimising Phinehas' ascendancy to the high priesthood, and justifying the War against the Midianites in Numbers 31.[3] Unlike the non-P text in 25:1–5, there is no indication that there is anything particularly wrong with Kozbi as a woman or a foreigner, nor are she and Zimri accused of sexual transgression; they are both simply people from categories forbidden to encroach on the Tabernacle. Only the fact that she is a Midianite princess is used as a pretext for the War against the Midianites.[3]

Ethics

Scholarly discussions

Susan Niditch (1995) explained that the 'priestly ideology of war in Numbers 31' regarded all enemies as unclean, and therefore 'deserving of God's vengeance', except those still in possession of feminine virginity: "Female children who have not lain with a man are clean slates in terms of their identity, unmarked by the enemy, and, after a period of purification, can be absorbed into the people Israel."[30]

Hamilton (2005) called Numbers 31 a "gruesome chapter, where only young virgin girls may be spared (...), and not even young boys are exempted". He argued that the two major concerns of Number 31 are the idea that war is a defiling activity, but Israelite soldiers need to be ritually pure, so they may only fight wars for a holy cause, and are required to cleanse themselves afterwards to restore their ritual purity.[23] The Israelite campaign against Midian was blessed by Yahweh, and could therefore be considered a holy war.[23] Simultaneously, however, the Israelite soldiers are said to be defiled by the killing, and in need of a seven-day purification of their bodies, clothes and metal possessions, and to require "atonement for ourselves before Yahweh" (verse 50).[23] Thus, the use of military violence, even if divinely mandated, is cast as a negative act that, in order to be erased, requires ritual cleansing of the body and possessions, as well as sacrifice in the form of 0.2% share of the soldiers' spoils as a tribute to Yahweh.[23][1][3]

Olson (2012) wrote that "the bulk of the chapter deals with the purification of soldiers and booty from the impurity of war and the allotment of the spoils," while "the actual battle is summarized in two verses".[2] The Israelite soldiers' actions closely followed the holy war regulations set out in Deuteronomy 20:14: "You may, however, take as your booty the women, the children, livestock, and everything else in the town, all its spoil," but in this case, Moses was angry because he also wanted the male children and non-virgin women to be killed, a marked departure from these regulations according to Olson.[2] He concluded: "Many aspects of this holy war text may be troublesome to a contemporary reader. But understood within the symbolic world of the ancient writers of Numbers, the story of the war against the Midianites is a kind of dress rehearsal that builds confidence and hope in anticipation of the actual conquest of Canaan that lay ahead."[2]

Brown (2015) stated: "This command to kill all but the virgin girls is without precedent in the Pentateuch. However, [Judges 21] precisely parallels Moses's command. (...) Like Num 25, the story recounted in Judges 19–21 centers on the danger of apostasy, but its tale of civil war and escalating violence also emphasizes the tragedy that can result from the indiscriminate application of [vengeance]. The whole account is highly ironic: the Israelites set out to avenge the rape of one woman, only to authorize the rapes of six hundred more. They regret the results of one slaughter, so they commit another to repair it."[4]: 77–78

Allan (2019) remarked: "God's work or not, this is military behaviour that would be tabooed today and might lead to a war crimes trial."[9]

According to the Book of Exodus, the Midianites had sheltered Moses during his 40-year voluntary exile after killing an Egyptian (Exodus 2:11–21), the Midianite priest Jethro/Reuel/Hobab[note 7] acted positively towards Yahweh in Exodus chapter 12, and his daughter Zipporah became Moses' wife (Exodus 2:21).[note 8] Scholars find it difficult to explain how Moses commanded the Israelites to exterminate and enslave the entire Midianite people while having a Midianite wife and father-in-law.[2]

Religious discussions

Numbers 31 and similar biblical episodes are sometimes referred to in religious morality debates between apologists and critics of religion. Rabbi and scholar Shaye J. D. Cohen (1999) argued that "the implications of Numbers 31:17–18 are unambiguous (...) we may be sure that for yourselves means that the warriors may "use" their virgin captives sexually," adding that Shimon bar Yochai understood the passage 'correctly'. On the other hand, he noted that other rabbinical commentaries such as B. and Y. Qiddushin and Yevamot claimed "that for yourselves meant "as servants." Later apologists, both Jewish and Christian, adopted the latter interpretation."[32]

In The Age of Reason (1795), Thomas Paine wrote about the chapter: "Among the detestable villains that in any period of the world would have disgraced the name of man, it is impossible to find a greater than Moses, if this account be true. Here is an order to butcher the boys, to massacre the mothers, and debauch the daughters."[31] Richard Watson, the Bishop of Llandaff, sought to refute Paine's arguments:[31]

| “ | I see nothing in this proceeding, but good policy, combined with mercy. The young men might have become dangerous avengers of, what they would esteem, their country's wrongs; the mothers might have again allured the Israelites to the love of licentious pleasure and the practice of idolatry, and brought another plague upon the congregation; but the young maidens, not being polluted by the flagitious habits of their mothers, nor likely to create disturbance by rebellion, were kept alive. You [=Paine] give a different turn to the matter; you say—"that thirty-two thousand women-children were consigned to debauchery by the order of Moses."—Prove this, and I will allow that Moses was the horrid monster you make him—prove this, and I will allow that the Bible is what you call it—a book of lies, wickedness, and blasphemy"... The women-children were not reserved for the purposes of debauchery, but of slavery;—a custom abhorrent from our manners, but every where practiced in former times, and still practiced in countries where the benignity of the christian religion has not softened the ferocity of human nature. | ” |

| — Richard Watson, the Bishop of Llandaff, An Apology for the Bible, in a series of letters, addressed to Thomas Paine, author of a book entitled, The Age of Reason (1796)[33] | ||

Debating Baptist minister Al Sharpton in 2007, atheist writer Christopher Hitchens argued that the Binding of Isaac and the extermination of the Amalekites were immoral divine commandments in the Old Testament, and recalled the previous debate: "The Bishop of Llandaff, in an argument with Thomas Paine, once said, "Well, when it says keep the women," as Paine had pointed out, he said, "I'm sure God didn't mean just to keep them for immoral purposes." But what does the Bishop of Llandaff know about that? It says, "Kill all the men, kill all the children, and keep the virgins." I think I know what they had in mind. I don't think it's moral teaching.'[34]

In 2010, Hitchens mocked the Ten Commandments for banning adultery but not rape: "Then again, what about rape? It seems to be very strongly recommended, along with genocide, slavery, and infanticide, in Numbers 31:1–18, and surely constitutes a rather extreme version of sex outside marriage."[35]

In the 2006 documentary The Root of All Evil? Part 2: The Virus of Faith, Richard Dawkins condemned Moses' acts in Numbers 31, asking: "How is this story of Moses morally distinguishable from Hitler's rape of Poland, or Saddam Hussein's massacre of the Kurds and the Marsh Arabs?" He contrasted this behaviour with Moses' own Commandment of Thou shalt not kill.[36][37]

Seth Andrews wrote in Deconverted (2012) that Numbers 31 was one of several parts of the Bible that made him seriously question the Christian God's ethics, claiming that his Christian friends and family did not have satisfactory answers, and ultimately did not really care to think about the moral implications of such texts.[38]

Neeper (2012) called Numbers 31:17–18 'appalling': "Instead of trying to "save" the people of Midian, [Moses] orders many of their deaths. The "lucky" people, the virgin girls who are allowed to live, are made into sex slaves for disgusting, homicidal post hoc mercenaries that do all of their bidding from a man who says that a god that (no one can see) tells them to do. This is one of the most sickening things in the so-called "Holy" Bible."[39]

Christian apologist John Berea (2017) speculated that Balaam was 'dismissed without pay by king Balak of Moab', and then set up the Midianite women to seduce the Israelite men to sexual immorality and idolatry in the same manner as he had previously done with the Moabite women. The execution of Midianite women who had had sex with (Israelite) men was therefore a just punishment for 'compromising the men of Israel', while turning prisoners into sex slaves was supposedly 'inconsistent with the many other laws against sexual immorality'. Taking the surviving virgin women and girls "as servants and integrating them into Israel may have been the best among lousy alternatives," John Berea concluded.[40]

Fate of the 32 virgins

It's not clear what happened to Yahweh's 0.1% share of the spoils of war, including 808 animals (verses 36–39) and 32 human virgin women/girls (verse 40), who are entrusted to the Levites, who are responsible for maintaining Yahweh's tabernacle (verses 30 and 47).[note 9] Two Hebrew terms are used to indicate they are a 'tribute' or 'levy' that is 'offered' or 'contributed' to Yahweh:

- מֶ֙כֶס֙ me·ḵes or ham·me·ḵes (verses 28, 37 and 41), generally translated as 'tribute', 'tax' or 'levy'.[42] Outside these three occurrences in Numbers 31, it appears nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible. It is also attested in Ugaritic as mekes and in Akkadian as miksu.[43] An inflection of mekes is וּמִכְסָ֥ם ū·miḵ·sām, occurring only in verses 38, 39 and 40.[44]

- תְּרוּמַ֥ת tə-rū-maṯ (verses 29 and 41); the term terumah (plural: terumat) is generally translated as '(heave) offering' or 'contribution' and is associated with heave offerings.[45]

Some scholars have concluded that these 32 human virgins were to be sacrificed to Yahweh as a burnt offering along with the animals. For example, Carl Falck-Lebahn (1854) compared the incident with the near-sacrifice of Iphigenia in Greek mythology, claiming: "According to Levit. xxvii, 29, sacrifices of human victims were clearly established among the Jews." After recounting the story of Jephthah's daughter in Judges 11, he reasoned: "...the Jews (according to Numbers, chap 31) took 61,000 asses, 72,000 oxen, 675,000 sheep, and 32,000 virgins (whose fathers, mothers, brothers &c., were butchered). There were 16,000 girls for the soldiers, 16,000 for the priests; and on the soldiers' share there was levied a tribute of 32 virgins for the Lord. What became of them? The Jews had no nuns. What was the Lord's share in all the wars of the Hebrews, if it was not blood?"[46]

Pluger (1995) cited Exodus 17, Numbers 31, Deuteronomy 13 and 20 as examples of human sacrifice demanded by Yahweh, adding that according to 1 Samuel 15, Saul "lost his kingship of Israel because he had withheld the human sacrifice that Yahweh, the god of Israel, expected as his due after a war."[47] Niditch (1995) remarked that, at the time of her writing, "increasingly scholars suggest that Israelites engaged in state-sponsored rituals of child sacrifice".[30]: 404 Although "[s]uch ritual activity is condemned by Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and other biblical writers (e.g., Lev 18:21, Deut 12:31, 18:10; Jer 7:30–31, 19:5; Ezek 20:31), and the seventh-century reformer king Josiah sought to put an end to it, [the] notion of a god who desires human sacrifice may well have been an important thread in Israelite belief."[30]: 404–405 She cited the Mesha Stele as evidence that the neighbouring Moabites also performed human sacrifices with prisoners of war to their god Chemosh after successfully attacking an Israelite city in the 9th century BCE.[30]: 405 Before the 7th-century BCE reformers of king Josiah of the southern Kingdom of Judah tried to end the practice of human/child sacrifice, it appears to have been commonplace in Israelite military culture.[30]: 406

Other scholars have concluded that the virgins and animals were kept alive and used by the Levites as their share of the spoils. Some even posited that human sacrifice (especially child sacrifice) was foreign to the Israelites, thus making the possibility of sacrificing the Midianite virgins unfeasible.[30]: 404 Keil and Delitzsch (1870) argued the 32 were enslaved: "Of the one half the priests received 675 head of small cattle, 72 oxen, 61 asses, and 32 maidens for Jehovah; and these Moses handed over to Eleazar, in all probability for the maintenance of the priests, in the same manner as the tithes (Numbers 18:26–28, and Leviticus 27:30–33), so that they might put the cattle into their own flocks (Numbers 35:3), and slay oxen or sheep as they required them, whilst they sold the asses, and made slaves of the gifts; and not in the character of a vow, in which case the clean animals would have had to be sacrificed, and the unclean animals, as well as the human beings, to be redeemed (Leviticus 27:2–13)."[48]

See also

- Ethics in the Bible

- Judaism and warfare

- Levite's concubine (Benjamite War, Judges 19–21)

- Moses in rabbinic literature

- The Bible and violence

- Women in the Bible

Notes

- ↑ Yahweh's name, written as 'YHWH' in the Hebrew Bible, has traditionally been rendered in English as the LORD (Adonai) or God by Jews and Christians. See Names of God in Judaism and Names of God in Christianity.

- ↑ The generations concept was first introduced by Jacob Milgrom (1990), who divided the Book of Numbers in three parts: the "generation of the Exodus" spanned the first two parts at Sinai (Num 1:1–10:10) and Kadesh (Num 10:11–22:1), and the "generation of the conquest" took up the third part in Moab/Transjordan (Num 22:2–36:13).[16]

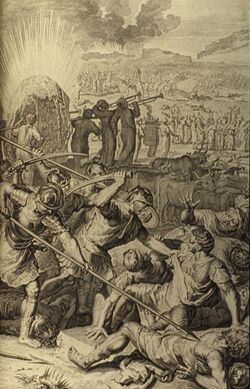

- ↑ In this interpretation of Numbers 25, Phinehas killed the Israelite man Zimri and the Midianite princess Kozbi (verse 7–8) as they were having sex in an ordinary tent in the Israelite military camp (verse 6) at Shittim near Mount Peor (verses 1–3). Outside the tents, people lay dead; apparently these are Israelites struck by the plague (verses 8–9). On the edge of the camp, soldiers stand on guard. Just outside the camp, a number of people are impaled (verse 4–5): the chiefs of the Israelite men, who engaged in sexual immorality with Moabite women and worshipped their gods (verse 1–3); this last act appears to be shown in the far background, with people on a mountain gathering around a pole, perhaps a Moabite godly idol. Engraving from Historie des Ouden en Nieuwen Testaments : verrykt met meer dan vierhonderd printverbeeldingen in koper gesneeden) ("History of the Old and New Testaments: enriched with more than four hundred printed illustrations cut in copper") (1700), published by David Martin in Amsterdam.

- ↑ "While Israel was staying in Shittim, the men began to indulge in sexual immorality with Moabite women, who invited them to the sacrifices to their gods. The people ate the sacrificial meal and bowed down before these gods. So Israel yoked themselves to the Baal of Peor. And Yahweh's anger burned against them." (Numbers 25:1–3 New International Version)[18]

- ↑ "Yahweh said to Moses: 'Treat the Midianites as enemies and kill them. They treated you as enemies when they deceived you in the Peor incident involving their sister Kozbi, the daughter of a Midianite leader, the woman who was killed when the plague came as a result of that incident.'" (Numbers 25:16–18 New International Version).[17]

- ↑ 2 Peter 2:4–10 claims Lot was 'a righteous man', and that this is the reason why the god Yahweh had spared him and his family when he destroyed the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 19.

- ↑ Moses' father-in-law is variously identified as Jethro (Exodus 3:1, 4:18, 18:1–12), Reuel (Exodus 2:18; Numbers 10:29) or Hobab (Judges 4:11); Hobab is also identified as Reuel's son (Numbers 10:29). All three are identified as Midianites.

- ↑ Although Numbers 12 refers to Moses' wife as a Cushite, it's unclear if this refers to Zipporah or another unnamed second wife of Moses; some scholars think cushite refers to her beauty rather than her ethnicity.

- ↑ For example, Methodist theologian Joel L. Watts (2019) wrote: "Only 32 men [sic] were given to the priests for the deity, leaving us to wonder if this surrendering was to die or to work."[41]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Knohl, Israel (2007). The Sanctuary of Silence: The Priestly Torah and the Holiness School. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. pp. 96–98. ISBN 9781575061313. https://books.google.com/books?id=eqs4p89KkyQC&pg=PA97. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 Olson, Dennis T. (2012). "Numbers 31. War against the Midianites: Judgment for Past Sin, Foretaste of a Future Conquest". Numbers. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 176–180. ISBN 9780664238827. https://books.google.com/books?id=jlFKK7xkxJsC&pg=PA176. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 Shectman, Sarah (2009). Women in the Pentateuch: A Feminist and Source-critical Analysis. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. p. 165. ISBN 9781906055721. https://books.google.com/books?id=elUeQSPk19MC&pg=PA165. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Brown, Ken (2015). "Vengeance and Vindication in Numbers 31". Journal of Biblical Literature (The Society of Biblical Literature) 134 (1): 65–84. doi:10.15699/jbl.1341.2015.2561. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.15699/jbl.1341.2015.2561. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ↑ Enns 2012, p. 5.

- ↑ Finkelstein, I., Silberman, NA., The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, p.68–69

- ↑ McDermott, John J. (2002). Reading the Pentateuch: a historical introduction. Pauline Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8091-4082-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=Dkr7rVd3hAQC&pg=PA21. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ↑ McDermott 2002, p. 21.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Allan, Keith (2019). The Oxford Handbook of Taboo Words and Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780198808190. https://books.google.com/books?id=XflyDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA15. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "Numbers 31 (New International Version)". Biblehub.com. https://biblehub.com/niv/numbers/31.htm.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Brian Dunning (2 February 2010). "Did Jewish Slaves Build the Pyramids?". Skeptoid. https://skeptoid.com/episodes/4191. "Israel itself did not exist until approximately 1100 BCE when various Semitic tribes joined in Canaan to form a single independent kingdom, at least 600 years after the completion of the last of Egypt's large pyramids. Thus it is not possible for any Israelites to have been in Egypt at the time, either slave or free; as there was not yet any such thing as an Israelite."

- ↑ Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and Other Deities in Ancient Israel. San Francisco/New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-0606-7416-8.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Bietak, Manfred (2015). "On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt". Quantitative Methods in the Humanities and Social Sciences (Springer): 17–35. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-04768-3_2. ISBN 978-3-319-04767-6. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-04768-3_2. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ William G. Dever (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8028-2126-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=6-VxwC5rQtwC&pg=PA99.

- ↑ Dever, William G. (1993). "What Remains of the House That Albright Built?". The Biblical Archaeologist (University of Chicago Press) 56 (1): 25–35. doi:10.2307/3210358. ISSN 0006-0895. "the overwhelming scholarly consensus today is that Moses is a mythical figure".

- ↑ Ehrlich, Carl S. (1995). "Review: NUMBERS. The JPS Torah Commentary: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation by Jacob Milgrom". Hebrew Studies (National Association of Professors of Hebrew) 36: 171–174. doi:10.1353/hbr.1995.0030. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27909476. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Numbers 25:18 Hebrew text analysis". Biblehub.com. 2011. https://biblehub.com/interlinear/numbers/25-18.htm.

"Numbers 25:18 English translations". Biblehub.com. 2011. https://biblehub.com/numbers/25-18.htm. - ↑ "Numbers 25 (New International Version)". Biblehub.com. https://biblehub.com/niv/numbers/25.htm.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "Numbers 31 Commentaries". Biblehub.com. 2011. https://biblehub.com/commentaries/numbers/31-1.htm.

- ↑ "Numbers 31 Commentary". 2021. https://biblehub.com/commentaries/barnes/numbers/31.htm.

- ↑ "Numbers 25 Commentary". 2021. https://biblehub.com/commentaries/benson/numbers/25.htm.

- ↑ "Numbers 31 Commentary". 2021. https://biblehub.com/commentaries/poole/numbers/31.htm.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Hamilton, Victor P. (2005). Handbook on the Pentateuch: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books. p. 371. ISBN 9781585583003. https://books.google.com/books?id=qVcVWPXuMsAC&pg=PT371. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ "Psalm 106". Biblehub.com. https://biblehub.com/niv/psalms/106.htm.

- ↑ "Numbers 25:6 Commentaries". Biblehub.com. 2011. https://biblehub.com/commentaries/numbers/25-6.htm.

- ↑ "Numbers 8:19 English translations". Biblehub.com. https://biblehub.com/numbers/8-19.htm.

- ↑ "Numbers 16 (New International Version)". Biblehub.com. https://biblehub.com/niv/numbers/16.htm.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Numeri 17 (Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling)" (in nl). debijbel.nl. https://debijbel.nl/bijbel/NBV/NUM.17/Numeri-17.

- ↑ "Numbers 17 (New International Version)". Biblehub.com. https://biblehub.com/niv/numbers/17.htm.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 Niditch, Susan (1995). "War in the Hebrew Bible and Contemporary Parallels". Word & World (Luther Seminary) 15 (4): 406. http://wordandworld.luthersem.edu/content/pdfs/15-4_Nations/15-4_Niditch.pdf. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Prickett, Stephen (March 2019). "Chapter 18 - The Bible". William Blake in Context (Cambridge University Press): 165–172. doi:10.1017/9781316534946.019. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/william-blake-in-context/bible/2B58F7815773C0FD5FD3D3987F76953A. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ Cohen, Shaye J. D. (1999). The Beginnings of Jewishness: Boundaries, Varieties, Uncertainties. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 255–256. ISBN 9780520926271. https://books.google.com/books?id=cvWq4tG4EhMC&pg=PA255. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ Watson, Richard (1797). An Apology for the Bible, in a series of letters, addressed to Thomas Paine, author of a book entitled, The Age of Reason. London: T. Evans. pp. 26–27. https://books.google.com/books?id=SfjWrKyRZD4C&pg=PA26. Retrieved 20 March 2021. (8th edition)

- ↑ "Christopher Hitchens and Al Sharpton A Debate: God Is Not Great". Celeste Bartos Forum. New York Public Library. 7 May 2007. https://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/events/hitchens5707.pdf.

- ↑ Christopher Hitchens (4 March 2010). "The New Commandments". Vanity Fair. https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2010/04/hitchens-201004.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (January 2006). "The Root of All Evil? - Part 2: The Virus of Faith" (documentary). The Root of All Evil?. Episode 2. Giordano Bruno Foundation. Retrieved 22 March 2021. : 26:52

- ↑ Parsley, Rod (2009). Culturally Incorrect: How Clashing Worldviews Affect Your Future. Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson. p. 21. ISBN 9781418572075. https://books.google.com/books?id=EDyWjusVuRAC&pg=PA21. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ↑ Andrews, Seth (2012). Deconverted. Outskirts Press. ISBN 978-1-4787-1656-3.

- ↑ Neeper, M. A. (2012). The Eyes of an Atheist: A Collection of Responses to Common Theistic Arguments. Trafford Publishing. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9781466946903. https://books.google.com/books?id=U8Vo4IuYrykC&pg=PA28. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ John Berea (2017). "Ancient Israel: Morality of the Conquest of Canaan". Berean Archive. http://bereanarchive.org/articles/history/ancient-israel-morality-of-the-conquest-of-canaan#Numbers-31.

- ↑ Watts, Joel L. (2019). Jesus as Divine Suicide: The Death of the Messiah in Galatians. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 71. ISBN 9781532657184. https://books.google.com/books?id=xpGpDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT71. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ "me·ḵes – Englishman's Concordance". Biblehub.com. 2011. https://biblehub.com/hebrew/meches_4371.htm.

"ham·me·ḵes – Englishman's Concordance". Biblehub.com. 2011. https://biblehub.com/hebrew/hammeches_4371.htm. - ↑ Keener, Craig S.; Walton, John H. (2017). NKJV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible, eBook: Bringing to Life the Ancient World of Scripture. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. p. 750. ISBN 9780310003618. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ct18DQAAQBAJ&pg=PT750. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ "ū·miḵ·sām – Englishman's Concordance". Biblehub.com. 2011. https://biblehub.com/hebrew/umichsam_4371.htm.

- ↑ "tə·rū·maṯ – Englishman's Concordance". Biblehub.com. 2011. https://biblehub.com/hebrew/terumat_8641.htm.

- ↑ Carl, Falck-Lebahn (1854). Selections from the German poets, with interlinear tr., notes and complete vocabularies, and a dissertation on mythology, by Falck Lebahn. London: Clarke, Beeton, & Co.. p. 291. https://books.google.com/books?id=pWoCAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA291. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ↑ Pfluger, Carl (1995). "Progress, Irony and Human Sacrifice". The Hudson Review (Hudson Review, Inc.) 48 (1): 72. doi:10.2307/3852059. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3852059. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ "Numbers 31:40 Commentaries". Biblehub.com. 2011. https://biblehub.com/commentaries/numbers/31-40.htm.

Literature

- Enns, Peter (2012). The Evolution of Adam. Baker Books. ISBN 9781587433153. https://books.google.com/?id=BNxeoqoTg-YC&pg=PA5.

- Knohl, Israel (1995). The Sanctuary of Silence: The Priestly Torah and the Holiness School. Augsburg Fortress. p. 97.

- Niditch, Susan (1993). "War, Women, and Defilement in Numbers 31". War in the Hebrew Bible: A Study in the Ethics of Violence. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 39–57. ISBN 9780195076387.

- Noth, Martin (1968). Numbers: a commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0664223205. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Numbers/SsTxhJcQrikC?hl=en.

External links

- Jewish translations:

- Bamidbar - Numbers - Chapter 31 (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- Numbers chapter 31. Bible Gateway