Social:Ugaritic

Ugaritic[1][2] (/ˌjuːɡəˈrɪtɪk, ˌuː-/[3]) is an extinct Northwest Semitic language known through the Ugaritic texts discovered by French archaeologists in 1928 at Ugarit,[4][5][6][7][8][9][10] including several major literary texts, notably the Baal cycle.[10][11]

Ugaritic has been called "the greatest literary discovery from antiquity since the deciphering of the Egyptian hieroglyphs and Mesopotamian cuneiform".[12]

Corpus

The Ugaritic language is attested in texts from the 14th through the early 12th century BC. The city of Ugarit was destroyed roughly 1190 BC.[13]

Literary texts discovered at Ugarit include the Legend of Keret or Kirta, the legends of Danel (AKA 'Aqhat), the Myth of Baal-Aliyan, and the Death of Baal. The latter two are also known collectively as the Baal Cycle. These texts reveal aspects of ancient Northwest Semitic religion in Syria-Palestine during the Late Bronze Age.

Edward Greenstein has proposed that Ugaritic texts might help solve biblical puzzles such as the anachronism of Ezekiel mentioning Daniel in Ezekiel 14:13–16[10] actually referring to Danel, a hero from the Ugaritic Tale of Aqhat.

Phonology

Ugaritic had 28 consonantal phonemes (including two semivowels) and eight vowel phonemes (three short vowels and five long vowels): a ā i ī u ū ē ō. The phonemes ē and ō occur only as long vowels and are the result of monophthongization of the diphthongs аy and aw, respectively.

| Labial | Interdental | Dental/Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | |||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | tˤ | k | q | ʔ | |||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | θ | s | sˤ | ʃ | x | ħ | h | ||

| voiced | ð | z | ðˤ | (ʒ)[decimal 1] | ɣ[decimal 2] | ʕ | ||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

The following table shows Proto-Semitic phonemes and their correspondences among Ugaritic, Akkadian, Classical Arabic and Tiberian Hebrew:

| Proto-Semitic | Ugaritic | Akkadian | Classical Arabic | Tiberian Hebrew | Imperial Aramaic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b [b] | 𐎁 | b | b | ب | b [b] | ב | b/ḇ [b/v] | 𐡁 | b/ḇ [b/v] |

| p [p] | 𐎔 | p | p | ف | f [f] | פ | p/p̄ [p/f] | 𐡐 | p/p̄ [p/f] |

| ḏ [ð] | 𐎏 | d; sometimes ḏ [ð] |

z | ذ | ḏ [ð] | ז | z [z] | 𐡃 (older 𐡆) | d/ḏ [d/ð] |

| ṯ [θ] | 𐎘 | ṯ [θ] | š | ث | ṯ [θ] | שׁ | š [ʃ] | 𐡕 (older 𐡔) | t/ṯ [t/θ] |

| ṱ [θʼ] | 𐎑 | ẓ [ðˤ]; sporadically ġ [ɣ] |

ṣ | ظ | ẓ [ðˤ] | צ | ṣ [sˤ] | 𐡈 (older 𐡑) | ṭ [tˤ] |

| d [d] | 𐎄 | d | d | د | d [d] | ד | d/ḏ [d/ð] | 𐡃 | d/ḏ [d/ð] |

| t [t] | 𐎚 | t | t | ت | t [t] | ת | t/ṯ [t/θ] | 𐡕 | t/ṯ [t/θ] |

| ṭ [tʼ] | 𐎉 | ṭ [tˤ] | ṭ | ط | ṭ [tˤ] | ט | ṭ [tˤ] | 𐡈 | ṭ [tˤ] |

| š [s] | 𐎌 | š [ʃ] | š | س | s [s] | שׁ | š [ʃ] | 𐡔 | š [ʃ] |

| z [dz] | 𐎇 | z | z | ز | z [z] | ז | z [z] | 𐡆 | z [z] |

| s [ts] | 𐎒 | s | s | س | s [s] | ס | s [s] | 𐡎 | s [s] |

| ṣ [tsʼ] | 𐎕 | ṣ [sˤ] | ṣ | ص | ṣ [sˤ] | צ | ṣ [sˤ] | 𐡑 | ṣ [sˤ] |

| l [l] | 𐎍 | l | l | ل | l [l] | ל | l [l] | 𐡋 | l [l] |

| ś [ɬ] | 𐎌 | š | š | ش | š [ʃ] | שׂ | ś [ɬ]→[s] | 𐡎 (older 𐡔) | s [s] |

| ṣ́ [(t)ɬʼ] | 𐎕 | ṣ | ṣ | ض | ḍ [ɮˤ]→[dˤ] | צ | ṣ [sˤ] | 𐡏 (older 𐡒) | ʿ [ʕ] |

| g [ɡ] | 𐎂 | g | g | ج | ǧ [ɡʲ]→[dʒ] | ג | g/ḡ [ɡ/ɣ] | 𐡂 | g/ḡ [ɡ/ɣ] |

| k [k] | 𐎋 | k | k | ك | k [k] | כ | k/ḵ [k/x] | 𐡊 | k/ḵ [k/x] |

| q [kʼ] | 𐎖 | q | q | ق | q [q] | ק | q [q] | 𐡒 | q [q] |

| ġ [ɣ] | 𐎙 | ġ [ɣ] | ḫ | غ | ġ [ɣ] | ע | ʿ [ʕ] | 𐡏 | ʿ [ʕ] |

| ḫ [x] | 𐎃 | ḫ [x] | خ | ḫ [x] | ח | ḥ [ħ] | 𐡇 | ḥ [ħ] | |

| ʿ [ʕ] | 𐎓 | ʿ [ʕ] | ḫ / e | ع | ʿ [ʕ] | ע | ʿ [ʕ] | 𐡏 | ʿ [ʕ] |

| ḥ [ħ] | 𐎈 | ḥ [ħ] | e | ح | ḥ [ħ] | ח | ḥ [ħ] | 𐡇 | ḥ [ħ] |

| ʾ [ʔ] | 𐎛 | ʾ [ʔ] | ∅ / ʾ | ء | ʾ [ʔ] | א | ʾ [ʔ] | 𐡀/∅ | ʾ/∅ [ʔ/∅] |

| h [h] | 𐎅 | h | ∅ | ه | h [h] | ה | h [h] | 𐡄 | h [h] |

| m [m] | 𐎎 | m | m | م | m [m] | מ | m [m] | 𐡌 | m [m] |

| n [n] | 𐎐 | n | n | ن | n [n] | נ | n [n] | 𐡍 | n [n] |

| r [r] | 𐎗 | r | r | ر | r [r] | ר | r [r] | 𐡓 | r [r] |

| w [w] | 𐎆 | w | w | و | w [w] | ו | w [w] | 𐡅 | w [w] |

| y [j] | 𐎊 | y | y | ي | y [j] | י | y [j] | 𐡉 | y [j] |

Writing system

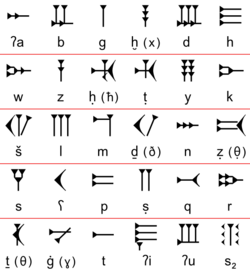

The Ugaritic alphabet is a cuneiform script used beginning in the 15th century BC. Like most Semitic scripts, it is an abjad, where each symbol stands for a consonant, leaving the reader to supply the appropriate vowel. Only after an aleph the vowel is indicated (’a, ’i, ’u). With other consonants one can often guess the unwritten vowel, and thus vocalize the text, from (a) parallel cases with an aleph, (b) texts where Ugaritic words are written in Akkadian cuneiform syllables, (c) comparison with other West-Semitic languages, for example Hebrew and Arabic, or (d) generalized vocalization rules.[14]

Although it appears similar to Mesopotamian cuneiform (whose writing techniques it borrowed), its symbols and symbol meanings are unrelated. It is the oldest example of the family of West Semitic scripts such as the Phoenician, Paleo-Hebrew, and Aramaic alphabets (including the Hebrew alphabet). The so-called "long alphabet" has 30 letters while the "short alphabet" has 22. Other languages (particularly Hurrian) were occasionally written in the Ugarit area, although not elsewhere.

Clay tablets written in Ugaritic provide the earliest evidence of both the Levantine ordering of the alphabet, which gave rise to the alphabetic order of the Hebrew, Greek, and Latin alphabets; and the South Semitic order, which gave rise to the order of the Ge'ez script. The script was written from left to right.

Grammar

Ugaritic is an inflected language, and as a Semitic language its grammatical features are highly similar to those found in Classical Arabic and Akkadian. It possesses two genders (masculine and feminine), three cases for nouns and adjectives (nominative, accusative, and genitive [also, note the possibility of a locative case]); three numbers: (singular, dual, and plural); and verb aspects similar to those found in other Northwest Semitic languages. The word order for Ugaritic is verb–subject–object (VSO), possessed–possessor (NG), and noun–adjective (NA). Ugaritic is considered a conservative Semitic language, since it retains most of the Proto-Semitic phonemes, the basic qualities of the vowel, the case system, the word order of the Proto-Semitic ancestor, and the lack of the definite article.

The word order for Ugaritic is verb–subject–object (VSO) and subject–object–verb (SOV),[15] possessed–possessor (NG), and noun–adjective (NA). Ugaritic is considered a conservative Semitic language, since it retains most of the phonemes, the case system, and the word order of the ancestral Proto-Semitic language.[16]

Word order

The word order for Ugaritic is Subject Verb Object (SVO), Verb Subject Object (VSO), possessed–possessor (NG), and noun–adjective (NA).

Morphology

Ugaritic, like all Semitic languages, exhibits a unique pattern of stems consisting typically of "triliteral", or 3-consonant consonantal roots (2- and 4-consonant roots also exist), from which nouns, adjectives, and verbs are formed in various ways: e.g. by inserting vowels, doubling consonants, and/or adding prefixes, suffixes, or infixes.

Verbs

Aspects

Verbs in Ugaritic have 2 aspects: perfect for completed action (with pronominal suffixes) and imperfect for uncompleted action (with pronominal prefixes and suffixes). Verb formation in Ugaritic (like all Semitic languages) is based on triconsonantal roots. Affixes inserted into the root form different meanings. Taking the root RGM (which means "to say") for example:

| Perfect | Imperfect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | ||||

| 1st | STEM-tu or STEM-tī | ʼa-STEM | ||

| RaGaMtu or RaGaMtī | َʼaRGuMu | |||

| 2nd | masculine | STEM-ta | ta-STEM | |

| RaGaMta | taRGuMu | |||

| feminine | STEM-ti | ta-STEM-īna | ||

| RaGaMti | taRGuMīna | |||

| 3rd | masculine | STEM-a | ya-STEM | |

| RaGaMa | yaRGuMu | |||

| feminine | STEM-at | ta-STEM | ||

| RaGaMat | taRGuMu | |||

| Dual | ||||

| 1st | STEM-nayā | na-STEMā | ||

| RaGaMnayā | naRGuMā | |||

| 2nd | masculine & feminine |

STEM-tumā | ta-STEM-ā(ni) | |

| RaGaMtumā | taRGuMā(ni) | |||

| 3rd | masculine | STEM-ā | ya-STEM-ā(ni) | |

| RaGaMā | yaRGuMā(ni) | |||

| feminine | STEM-atā | ta-STEM-ā(ni) | ||

| RaGaMatā | taRGuMā(ni) | |||

| Plural | ||||

| 1st | STEM-nū | na-STEM | ||

| RaGaMnū | naRGuMu | |||

| 2nd | masculine | STEM-tum(u) | ta-STEM-ū(na) | |

| RaGaMtum(u) | taRGuMū(na) | |||

| feminine | STEM-tin(n)a | ta-STEM-na | ||

| RaGaMtin(n)a | taRGuMna | |||

| 3rd | masculine | STEM-ū | ya-STEM-ū(na) | |

| RaGaMū | yaRGuMū(na) | |||

| feminine | STEM-ā | ta-STEM-na | ||

| RaGaMā | taRGuMna | |||

Moods

The imperfect (prefix conjugation) of Ugaritic verbs occurs in 5 moods:

| Mood | Verb[decimal 1] |

|---|---|

| Indicative | yargumu |

| Jussive | yargum |

| Volitive[decimal 2] | yarguma |

| Energic 1 | yargum(a)n |

| Energic 2 | yargumanna |

Imperative

The imperative probably takes three forms, qatal, qutul, and qitil, where the vowels correspond with the vowels in the imperfect. However, only examples of the first two types are known.

| a-type | i-type | u-type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Singular | masculine | pataḥ “open!” | no clear examples known |

rugum “say!” |

| feminine | pataḥī | rugumī | ||

| 2 Dual | masculine | pataḥā | rugumā | |

| feminine | ? | ? | ||

| 2 Plural | masculine | pataḥū | rugumū | |

| feminine | pataḥā (?) | rugumā (?) |

Participles

The paradigm of the active participle (G stem, verb mlk, “to be king”) is as follows:

| Singular | masculine | māliku | “reigning (king)” |

| feminine | malik(a)tu | “reigning (queen)” | |

| Plural | masculine | malikūma | “reigning (kings)” |

| feminine | mālikātu | “reigning (queens)” |

The passive participle is quite rare. There seem to be two forms (verbs rgm “to say”, ẖrm “to divide”):

| u-form | i-form | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | masculine | ragūmu “said, spoken” | ẖarimu “divided” |

| feminine | ragūm(a)tu | ẖarim(a)tu | |

| Plural | masculine | ? | ? |

| feminine | ragūmātu | ẖarimātu |

Infinitives

Like other Semitic languages, Ugaritic has two infinitives, the infinitive absolute and the infinitive construct. However, in Ugaritic the two have an identical form. The usual form is halāku (“to go”, verb hlk), but a few verbs use an alternative form *hilku, for example niģru, “to guard” (verb nģr).

The infinitive absolute is often used preceding a perfect or imperfect verbal form, to put emphasis on that following verbal form. Such an infinive absolute may be translated as “verily, certainly, absolutely”. For example, halāku halaka, “he certainly goes” (literally, “to go! he goes”). An isolated infinitive absolute may also be used instead of any perfect, imperfect, or imperative verbal form.

The infinitive construct is often used after the prepositions l (“to”) and b (“in, by”): bi-ša’āli “in asking, by asking, while asking” (verb š’al “to ask”; note that after the preposition b (bi) the genitive of the infinitive is used).

Weak Verbs

In Ugaritic, "weak verbs" are verbs whose roots contain a weak consonant, that is, a consonant that may disappear in some forms, or change into another consonant. Weak consonants are w and y, and also n, h, and in one case l (lqḥ, “to take”), if these are the first root consonant. Weak verbs exhibit irregular patterns in their conjugation due to the inherent instability of the weak consonants, often leading to phonetic variations. This phenomenon is akin to that observed in other Semitic languages, including Hebrew.

For instance, the Ugaritic verb yrd, “to go down”, is a weak verb: its imperative is rd /rid/ “go down!”, without the y consonant. The verb hlk, “to go”, has the imperative lk /lik/ “go!”, without the h. Due to their weak consonants, weak verbs can undergo phonetic changes, such as the assimilation of waw (w) to yod (y), especially in the absence of an intervening vowel. This characteristic impacts the verb's inflection, resulting in variations that are atypical compared to regular (strong) verbs.[17]

In Ugaritic there also exist "doubly weak verbs", which contain two weak consonants.

Patterns

Ugaritic verbs occur in 10 reconstructed patterns or binyanim:

| Verb Patterns | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hebrew equivalent | Active voice | Passive voice | |||||

| Perfect (3rd sg. masc.) | Imperfect (3rd sg. masc.) | Perfect (3rd sg. masc.) | Imperfect (3rd sg. masc.) | ||||

| G stem (simple) and Gp (passive) | qal and qal passive | paʻala, paʻila, paʻula | yapʻulu, yapʻalu, yapʻilu | puʻila | yupʻalu | ||

| Gt stem (simple reflexive) | ʼiptaʻala | yaptaʻalu | (?) | (?) | |||

| N stem (reciprocal passive) | niphʻal | nap(a)ʻala | yappaʻilu <<(*yanpaʻilu) | n/a | |||

| D stem (factitive) and Dp (passive) | piʻʻel and puʻʻal | paʻʻala | yapaʻʻilu | puʻʻila | yupaʻʻalu | ||

| tD stem (factitive reflexive) | hithpaʻʻel | tapaʻʻala | yatapaʻʻalu | (?) | (?) | ||

| L stem (intensive or factitive) and Lp (passive) | pôlel and pôlal | pāʻala | yupāʻilu | (?) | (?) | ||

| Š stem (causative) and Šp (passive) | hiphʻil and hophʻal | šapʻala | yašapʻilu[decimal 1] | šupʻila | yupaʻilu[decimal 2] | ||

| Št stem (causative reflexive) | hištaph‘al | ʼištapʻala | yaštapʻilu | (?) | (?) | ||

| (?) C stem (causative internal pattern) | (?) | yapʻilu | n/a | ||||

| R stem (factitive) (biconsonantal roots) | paʻlala (e.g. karkara) | yapaʻlalu (e.g. yakarkaru) | (?) | (?) | |||

- ↑ Gordon, Cyrus (1947). Ugaritic Handbook, I. Pontifical Biblical Institute. p. 72. https://archive.org/details/ugaritichandbook0000gord/page/72/mode/2up?view=theater.

- ↑ yušapʻalu?

Nouns

Nouns in Ugaritic can be categorized according to their inflection into: cases (nominative, genitive, and accusative), state (absolute and construct), gender (masculine and feminine), and number (singular, dual, and plural).

Case

Ugaritic has three grammatical cases corresponding to: nominative, genitive, and accusative. Normally, singular nouns take the ending -u in the nominative, -i in the genitive and -a in the accusative. Using the word malk- (king) and malkat- (queen) for example:

| Nominative | Genitive | Accusative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | malku | malki | malka |

| Feminine | malkatu | malkati | malkata |

As in Arabic, some exceptional nouns (known as diptotes) have the suffix -a in the genitive. There is no Ugaritic equivalent for Classical Arabic nunation or Akkadian mimation.

State

Nouns in Ugaritic occur in two states: absolute and construct. If a noun is followed by a genitival attribute (noun in the genitive or suffixed pronoun) it becomes a construct (denoting possession). Otherwise, it is in the absolute state. Ugaritic, unlike Arabic and Hebrew, has no definite article.

Gender

Nouns which have no gender marker are for the most part masculine, although some feminine nouns do not have a feminine marker. However, these denote feminine beings such as ʼumm- (mother). /-t/ is the feminine marker which is directly attached to the base of the noun.

Number

Ugaritic distinguishes between nouns based on quantity. All nouns are either singular when there is one, dual when there are two, and plural if there are three or more.

Singular

The singular has no marker and is inflected according to its case.

Dual

The marker for the dual in the absolute state appears as /-m/. However, the vocalization may be reconstructed as /-āmi/ in the nominative (such as malkāmi "two kings") and /-ēmi/ for the genitive and accusative (e.g. malkēmi). For the construct state, it is /-ā/ and /-ē/ respectively.

Plural

Ugaritic has only regular plurals (i.e. no broken plurals). Masculine absolute state plurals take the forms /-ūma/ in the nominative and /-īma/ in the genitive and accusative. In the construct state they are /-ū/ and /-ī/ respectively. The female afformative plural is /-āt/ with a case marker probably following the /-t/, giving /-ātu/ for the nominative and /-āti/ for the genitive and accusative in both absolute and construct state.

Adjectives

Adjectives follow the noun and are declined exactly like the preceding noun.

Personal pronouns

Independent personal pronouns

Independent personal pronouns in Ugaritic are as follows (some forms are lacking because they are not in the corpus of the language):

| Person | singular | dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | ʼanā, ʼannāku "I" | ʾanaḥnu "we" | ||

| 2nd | masculine | ʼatta "you" | ʼattumā "you two" | ʼattumu "you all" |

| feminine | ʼatti "you" | ʼattina "you all" | ||

| 3rd | masculine | huwa[decimal 1] "he" | humā "them two" | humu[decimal 1] "they" |

| feminine | hiya[decimal 1] "she" | hinna "they" | ||

Suffixed (or enclitic) pronouns

Suffixed (or enclitic) pronouns (mainly denoting the genitive and accusative) are as follows:

| Person | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | -ya[decimal 1] "my" | -nayā "our" | -na, -nu "our" | |

| 2nd | masculine | -ka "your" | -kumā "your" | -kum- "your" |

| feminine | -ki "your" | -kin(n)a "your" | ||

| 3rd | masculine | -hu "his" | -humā "their" | -hum- "their" |

| feminine | -ha "her" | -hin(n)a "their" | ||

- ↑ -nī is used for the nominative, i.e. following a verb denoting the subject.

Numerals

The following is a table of Ugaritic numerals:

| Number | Masculine | Feminine |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ʼaḥḥadu | ʼaḥattu |

| 2 | ṯinā[decimal 1] | ṯittā[decimal 1] |

| 3 | ṯalāṯu | ṯalāṯatu |

| 4 | ʼarbaʻu | ʼarbaʻatu |

| 5 | ḫam(i)šu | ḫam(i)šatu |

| 6 | ṯiṯṯu | ṯiṯṯatu |

| 7 | šabʻu | šabʻatu |

| 8 | ṯamānu | ṯamānītu |

| 9 | tišʻu | tišʻatu |

| 10 | ʻaš(a)ru | ʻaš(a)ratu |

| 20 | ʻašrāma [decimal 2] | |

| 30 | ṯalāṯūma [decimal 2] | |

| 100 | miʼtu | |

| 200 | miʼtāma | |

| 1000 | ʼalpu | |

| 10000 | ribbatu[decimal 2] | |

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Segert, Stanislav (1984). A Basic Grammar of Ugaritic Language. University of California Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780520039995. https://books.google.com/books?id=9Yo-UShpt1kC.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ibid., p. 54

Ordinals

The following is a table of Ugaritic ordinals:

| Number | Masculine | Feminine |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | prʿ | prʿt |

| 2 | ṯanū | ṯanītu[decimal 1] |

| 3 | ṯalīṯu | ṯalīṯatu |

| 4 | rabīʻu | rabīʻatu |

| 5 | ḫamīšu | ḫamīšatu |

| 6 | ṯadīṯu | ṯadīṯatu |

| 7 | šabīʻu | šabīʻatu |

| 8 | ṯamīnu | ṯamīnatu |

| 9 | tašīʻu | tašīʻatu |

- ↑ These are reconstructed for the imperfect simple active pattern (G stem).

Sample Texts

Here is a fragment from the epic “Baal” cycle (KTU tablet 1.4 column 5):

| Ugaritic[lower-alpha 1][18] | vocalized | English |

|---|---|---|

| w bn bht ksp w ḫrṣ bht ṭhrm ’iqn’im | wa-banayū bahatū kaspa wa-ḫurāṣa, bahatū ṭuḥūrīma ’iqn’īma |

“And build a house of silver and gold, a house of pure lapis lazuli.” |

From another poem (KTU 1.91):

| k t‘rb ‘ṯtrt sd bt mlk k t‘rbn ršpm bt mlk | kî ta‘rubu ‘Aṯtaratu-Sadi bêta malki, kî ta‘rubūna Rašapūma bêta malki |

“When Athtart of the Field enters the house of the king, when the Reshaphim enter the house of the king” |

From a letter (KTU 2.19):

| nqmd mlk ’ugrt ktb spr hnd | Niqmaddu malku ’Ugarīti kataba sipra hānādū | “Niqmaddu, king of Ugarit, has written this document.” |

From a “contract” (KTU 3.4):

| l ym hnd ’iwr[k]l pdy ’agdn | le-yômi hānādū ’Iwrikallu padaya ’Agdena | “From this day, Iwrikallu has redeemed Agdenu.” |

See also

- Ugarit

- Ugaritic alphabet

- Northwest Semitic languages

- Central Semitic languages

- Semitic Languages

- Proto-Semitic language

Notes

- ↑ Ugaritic text does not include many vowels which would have been present in spoken language

References

- Citations

- ↑ Rendsburg, Gary A. (1987). "Modern South Arabian as a Source for Ugaritic Etymologies". Journal of the American Oriental Society 107 (4): 623–628. doi:10.2307/603304. https://bildnercenter.rutgers.edu/docman/rendsburg/59-modern-south-arabian-as-a-source-for-ugaritic-etymologies/file. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ↑ Rendsburg, Gary A. “Modern South Arabian as a Source for Ugaritic Etymologies”. In: Journal of the American Oriental Society 107, no. 4 (1987): 623–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/603304.

- ↑ "Ugaritic". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Ugaritic.

- ↑ Watson, Wilfred G. E.; Wyatt, Nicolas (1999). Handbook of Ugaritic Studies. Brill. p. 91. ISBN 978-90-04-10988-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=0Z2Jo01iq1YC&pg=PA91.

- ↑ Ugaritic is alternatively classified in a "North Semitic" group, see Lipiński, Edward (2001). Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar. Peeters Publishers. p. 50. ISBN 978-90-429-0815-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=IiXVqyEkPKcC&pg=PA50.

- ↑ Woodard, Roger D. (2008-04-10) (in en). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9781139469340. https://books.google.com/books?id=vTrT-bZyuPcC.

- ↑ Goetze, Albrecht (1941). "Is Ugaritic a Canaanite Dialect?". Language 17 (2): 127–138. doi:10.2307/409619.

- ↑ Kaye, Alan S. (2007-06-30) (in en). Morphologies of Asia and Africa. Eisenbrauns. p. 49. ISBN 9781575061092. https://books.google.com/books?id=gaktTQ8vq28C.

- ↑ Schniedewind, William; Hunt, Joel H. (2007). A Primer on Ugaritic: Language, Culture and Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-139-46698-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=L2T_4KVwpTQC&pg=PA20.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Greenstein, Edward L. (November 2010). "Texts from Ugarit Solve Biblical Puzzles" (in en). Biblical Archaeology Review 36 (6): 48–53, 70. https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archaeology-review/36/6/5. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ↑ Khan, Geoffrey; Bolozky, Shmuel; Fassberg, Steven et al., eds (2013). "Ugaritic and Biblical Hebrew". Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/2212-4241_ehll_EHLL_COM_00000287. ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3.

- ↑ Gordon, Cyrus H. (1965). The Ancient Near East. Norton. p. 99. https://archive.org/details/ancientneareast00gord.

- ↑ Huehnergard, John (2012). An Introduction to Ugaritic. Hendrickson Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-59856-820-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=IfHQx5FUZW8C.

- ↑ An example of this last method in Sivan, A Grammar of the Ugaritic Language, p. 116: "[The] pattern of correspondences between the thematic vowel with the second radical and the prefix vowel (thematic u and i taking prefix vowel a; thematic a taking prefix i) is helpful in reconstructing the vocalized forms of the G stem prefix conjugation."

- ↑ Wilson, Gerald H. (1982). "Ugaritic Word Order and Sentence Structure in KRT". Journal of Semitic Studies 27 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1093/jss/27.1.17.

- ↑ Segert, Stanislav (March 1985). A Basic Grammar of Ugaritic Language by Stanislav Segert – Hardcover – University of California Press. ISBN 9780520039995. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520039995/a-basic-grammar-of-ugaritic-language.

- ↑ Gordon, Cyrus Herzl (1998). Ugaritic Textbook. Roma: Gregorian Biblical BookShop. p. 13. ISBN 88-7653-238-2.

- ↑ Sivan, Daniel (2001) (in en). A Grammar of the Ugaritic Language. Brill. pp. 207–210.

- Bibliography

- Bordreuil, Pierre; Pardee, Dennis (2009). A Manual of Ugaritic: Linguistic Studies in Ancient West Semitic 3. Winona Lake, IN 46590: Eisenbraun's, Inc. ISBN 978-1-57506-153-5.

- Cunchillos, J.-L.; Vita, Juan-Pablo (2003). A Concordance of Ugaritic Words. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-258-7.

- del Olmo Lete, Gregorio; Sanmartín, Joaquín (2004). A Dictionary of the Ugaritic Language in the Alphabetic Tradition. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-13694-6. (2 vols; originally in Spanish, translated by W. G. E. Watson).

- Gibson, John C. L. (1977). Canaanite Myths and Legends. T. & T. Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-02351-3. (Contains Latin-alphabet transliterations of the Ugaritic texts and facing translations in English.)

- Gordon, Cyrus Herzl (1965). The Ancient Near East. W. W. Norton & Company Press. ISBN 978-0-393-00275-1. https://archive.org/details/ancientneareast0000gord.

- Greenstein, Edward L. (1998). "On a New Grammar of Ugaritic" in Past links: studies in the languages and cultures of the ancient near east: Volume 18 of Israel oriental studies. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-035-4. Found at Google Scholar.

- Hasselbach-Andee, Rebecca (2020). A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Languages. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1119193296.

- Huehnergard, John (2011). A Grammar of Akkadian, 3rd ed.. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-5750-6941-8.

- Moscati, Sabatino (1980). An Introduction to the Comparative Grammar of Semitic Languages, Phonology and Morphology. Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3-447-00689-7.

- Pardee, Dennis (2003). Rezension von J. Tropper, Ugaritische Grammatik (AOAT 273) Ugarit-Verlag, Münster 2000: Internationale Zeitschrift für die Wissenschaft vom Vorderen Orient. Vienna, Austria: Archiv für Orientforschung (AfO). P. 1-404 .

- Parker, Simon B. (ed.) (1997). Ugaritic Narrative Poetry: Writings from the Ancient World Society of Biblical Literature. Atlanta: Scholars Press. ISBN 978-0-7885-0337-5.

- Schniedewind, William M.; Hunt, Joel H. (2007). A Primer on Ugaritic: Language, Culture and Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5217-0493-9.

- Segert, Stanislav (1997). A Basic Grammar of the Ugaritic Language. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03999-8.

- Sivan, Daniel (1997). A Grammar of the Ugaritic Language (Handbook of Oriental Studies/Handbuch Der Orientalistik). Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-10614-7. A more concise grammar.

- Tropper, Josef (2000). Ugaritische Grammatik. Ugarit Verlag. ISBN 978-3927120907.

- Woodard, Roger D. (ed.) (2008). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68498-9.

Further reading

- Pardee, Dennis. “UGARITIC PROPER NOUNS”. In: Archiv Für Orientforschung 36/37 (1989): 390–513. UGARITIC PROPER NOUNS.

- Josef Tropper, Juan-Pablo Vita (2020). Lehrbuch der ugaritischen Sprache. Münster: Zaphon. ISBN 978-3-96327-070-3.

- Watson, Wilfred G.E. "From Hair to Heel: Ugaritic Terms for Parts of the Body". In: Folia Orientalia (pl) Vol. LII (2015), pp. 323–364.

- Watson, Wilfred G.E. "Terms for Occupations, Professions and Social Classes in Ugaritic: An Etymological Study". In: Folia Orientalia Vol. LV (2018), pp. 307–378. DOI: 10.24425/for.2018.124688

- Watson, Wilfred G.E. "Terms for Textiles, Clothing, Hides, Wool and Accessories in Ugaritic: An Etymological Study". In: Aula Orientalis 36/2 (2018): 359–396. ISSN 0212-5730.

- Watson, Wilfred G. E.. "Ugaritic Military Terms in the Light of Comparative Linguistics". In: At the Dawn of History: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of J. N. Postgate. Edited by Yağmur Heffron, Adam Stone and Martin Worthington, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, 2021. pp. 699–720. coaccess

External links

- Ugarit and the Bible. An excerpt from an online introductory course on Ugaritic grammar (the Quartz Hill School of Theology's course noted in the links hereafter). Includes a cursory discussion on the relationship between Ugaritic and Old Testament/Hebrew Bible literature.

- "El in the Ugaritic tablets" on the BBCi website gives many attributes of the Ugaritic creator and his consort Athirat.

- Abstract of Mark Smith, The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Text.

- Unicode Chart.

- RSTI. The Ras Shamra Tablet Inventory: an online catalog of inscribed objects from Ras Shamra-Ugarit produced at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Introduction to Ugaritic Grammar (Quartz Hill School of Theology)

- Introduction to Ugaritic Grammar (University of Chicago)

|