Removable singularity

In complex analysis, a removable singularity of a holomorphic function is a point at which the function is undefined, but it is possible to redefine the function at that point in such a way that the resulting function is regular in a neighbourhood of that point.

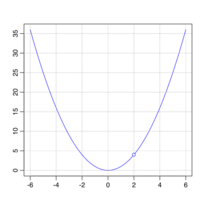

For instance, the (unnormalized) sinc function, as defined by

has a singularity at z = 0. This singularity can be removed by defining which is the limit of sinc as z tends to 0. The resulting function is holomorphic. In this case the problem was caused by sinc being given an indeterminate form. Taking a power series expansion for around the singular point shows that

Formally, if is an open subset of the complex plane , a point of , and is a holomorphic function, then is called a removable singularity for if there exists a holomorphic function which coincides with on . We say is holomorphically extendable over if such a exists.

Riemann's theorem

Riemann's theorem on removable singularities is as follows:

Theorem — Let be an open subset of the complex plane, a point of and a holomorphic function defined on the set . The following are equivalent:

- is holomorphically extendable over .

- is continuously extendable over .

- There exists a neighborhood of on which is bounded.

- .

The implications 1 ⇒ 2 ⇒ 3 ⇒ 4 are trivial. To prove 4 ⇒ 1, we first recall that the holomorphy of a function at is equivalent to it being analytic at (proof), i.e. having a power series representation. Define

Clearly, h is holomorphic on , and there exists

by 4, hence h is holomorphic on D and has a Taylor series about a:

We have c0 = h(a) = 0 and c1 = h'(a) = 0; therefore

Hence, where , we have:

However,

is holomorphic on D, thus an extension of .

Other kinds of singularities

Unlike functions of a real variable, holomorphic functions are sufficiently rigid that their isolated singularities can be completely classified. A holomorphic function's singularity is either not really a singularity at all, i.e. a removable singularity, or one of the following two types:

- In light of Riemann's theorem, given a non-removable singularity, one might ask whether there exists a natural number such that . If so, is called a pole of and the smallest such is the order of . So removable singularities are precisely the poles of order 0. A meromorphic function blows up uniformly near its other poles.

- If an isolated singularity of is neither removable nor a pole, it is called an essential singularity. The Great Picard Theorem shows that such an maps every punctured open neighborhood to the entire complex plane, with the possible exception of at most one point.

See also

- Analytic capacity

- Removable discontinuity

External links

|