Social:Amabie

Amabie (アマビエ) is a legendary Japanese mermaid or merman with a bird-beak like mouth and three legs or tail-fins, who allegedly emerges from the sea, prophesies either an abundant harvest or an epidemic, and instructed people to make copies of its likeness to defend against illness.

The amabie appears to be a variant or misspelling of the amabiko or amahiko (Japanese: アマビコ, アマヒコ, 海彦, 尼彦, 天日子, 天彦, あま彦), otherwise known as the amahiko-nyūdo (尼彦入道), also a prophetic beast depicted variously in different examples, being mostly as 3-legged or 4-legged, and said to bear ape-like (sometimes torso-less), daruma doll-like, or bird-like, or fish-like resemblance according to commentators.

This information was typically disseminated in the form of illustrated woodblock print bulletins (kawaraban) or pamphlets (surimono) or hand-drawn copies. The amabie was depicted on a print marked with an 1846 date. Attestation to the amabiko predating amabie had not been known until the discovery of a hand-painted leaflet dated 1844.

There are also other similar yogenjū (予言獣) that are not classed within the amabie/amabiko group, e.g., the arie (アリエ).

Legend

According to legend, an amabie appeared in Higo Province (Kumamoto Prefecture), around the middle of the fourth month, in the year Kōka-3 (mid-May 1846) in the Edo period. A glowing object had been spotted in the sea, almost on a nightly basis. The town's official went to the coast to investigate and witnessed the amabie. According to the sketch made by this official, it had long hair, a mouth like bird's bill, was covered in scales from the neck down and three-legged. Addressing the official, it identified itself as an amabie and told him that it lived in the open sea. It went on to deliver a prophecy: "Good harvest will continue for six years from the current year;[lower-alpha 1] if disease spreads, draw a picture of me and show the picture of me to those who fall ill." Afterward, it returned to the sea. The story was printed in the kawaraban (woodblock-printed bulletins), where its portrait was printed, and this is how the story disseminated in Japan.[1][2][3]

Amabiko group

There is only one unique record of an amabie, whose meaning is uncertain. It has been conjectured that this amabie was simply a miscopying of "amabiko",[lower-alpha 2] a yōkai creature that can be considered identical.[2][4] Like the amabie, the amabiko is a three-legged or multi-legged prophesizing creature which prescribes the display of its artistic likeness to defend against sickness or death.[5] However, the appearance of the amabie is said to be rather mermaid-like (the three-leggedness allegedly stemming from a mermaid type called jinjahime), and for this reason one researcher concludes there is not enough of a close resemblance in physical appearance between the two.[6]

Name variations

There are a dozen or more attestations of amabiko or amahiko (海彦; var. あま彦, 尼彦, 天彦) extant (counting the amabie),[7][12] with the copies dated 1843 (Tenpō 14) perhaps being the oldest.[14]

Locality of appearances

Four describe appearances in Higo Province, one report the Amabiko Nyūdo (尼彦入道, "the amahiko monk") in neighboring Hyuga Province (Miyazaki prefecture), another vaguely points to the western sea.[7][2]

Beyond those clustered in the south, two describe appearances in Echigo Province in the north.[7][2][lower-alpha 3]

The two oldest accounts (1844, 1846) do not closely specify the locations, but several accounts name specific village or counties (gun) that turn out to be nonexistent fictitious place names.[16]

Physical characteristics

The accompanying caption texts describes some as glowing (at night) or having ape-like voices,[17] but description of physical appearance is rather scanty. The newspapers and commentators however provide iconographic analysis of the pictorials (hand-painted and prints).[18]

The majority of pictorial represent the amabiko/amabie as 3-legged (or odd-number legged), with a couple cases rather like an ordinary quadruped.[23]

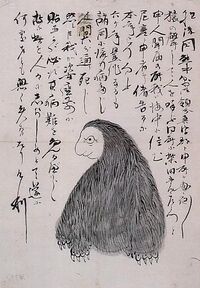

An amahiko/amabiko (海彦, ‘sea prince’),[27][29] whose appearance in Echigo Province is documented on a leaflet dated 1844 (Tenpō 15).[30]

The hand-copied pamphlet[lower-alpha 4] illustration depicts a creature rather like an ape with three legs, the legs seemingly projecting directly from the head (without any neck or torso in-between). The body and face are covered profusely with short hair, except for it being bald-headed. The eyes and ears are human-like, with a pouty or protruding mouth.[25][26] The creature appeared in the year 1844[33] and predicted doom to 70% of the Japanese population that year, which could be averted with its picture-amulet.[34]

- Amahiko-no-mikoto

The Amahiko-no-mikoto (天日子尊, ‘His Highness Heaven Prince’) was spotted in a rice paddy in Yuzawa, Niigata, as reported by the Tokyo Nichinichi Shinbun from 1875.[35][4] The crude newspaper illustration depicts a daruma doll-like or ape-like, hairless-looking four-legged creature.[20] This example stands out since it was emerged not in the ocean but in a wet rice field.[19] Also, the addition of the imperial/divine title of "-mikoto" has been noted by one researcher as resembling the name of one of the Amatsukami or "Heavenly Deities" of ancient Japan.[lower-alpha 5][19]

This creature in the crude drawing is said to resemble a daruma doll or an ape.[35][36]

- Ape-voiced

There are at least three examples of the amabiko[?] crying like apes.[38]

The texts of all three identify the place of appearance as Shinji-kōri[?] (眞字郡/眞寺郡), a non-existent county in Higo Province,[39][40][lower-alpha 6][lower-alpha 7] and names the discoverer who heard the ape voices heard by night and tracked down the amabiko as one Shibata Hikozaemon (or Goroemon/Gorozaemon).[lower-alpha 8][42][9]

One ape-voiced amabiko[?] (尼彦, ‘nun prince’) is represented by a hand-painted copy owned by Kōichi Yumoto,[43] an authority in the study of this yōkai.[44] This document has a terminus post quem of 1871 (Meiji 4) or later,[lower-alpha 9][32] The painting is said to depict a quadruped, with extremely close similarity in form to the mikoto (ape- or daruma doll-like) by commentators.[2][20] However, the amahiko[?] (あま彦)[lower-alpha 10] that cried like an ape (newspaper piece) is reported to have been drawn as a "three-legged monster".[45][lower-alpha 11][lower-alpha 12] And the encyclopedia example described the amabiko (アマビコ) as a kechō (怪鳥, ‘monstrous bird’) in its sub-heading.[9]

A tangential point of interest is that this text transcribed in the newspaper refers to "we amahiko who dwell in the sea", suggesting there are multiple numbers of the creature.[32]

- Glowing

The foregoing amahiko[?] (あま彦, ‘? prince’) was also described as a hikari-mono (光り物 glowing object).[45] The glowing is an attribute common to other examples, such as the amabie and amahiko (尼彦/あまひこ, ‘nun prince’) reported in the Nagano Shinbun.[22][41]

Amabiko (天彦, ‘heaven prince’) was also purportedly seen glowing at night in the offing of the Western Sea, during the Tenpō era (1830–1844), and illustrations were brought for sale at 5 sen apiece to Kasai-kanamachi village, Tokyo, as reported in another newspaper, dated 20 October 1881.[47] This creature allegedly predicted global-scale doom thirty-odd years ahead,[lower-alpha 13] conveniently coinciding with the time the peddlers were selling them, prompting researcher Eishun Nagano to comment that while the text may or may not have been genuinely composed in the Edo Period, the illustrations were probably contemporary,[48] though he guesses that the merchandise was surimono woodblock print.[49] The creature also professed to serve the heavenly Tenbu or Deva divinities (of Buddhism), even though he is presumably sea-dwelling.[19]

- Old man or monk

The amahiko[?] nyūdō (尼彦入道, ‘nun prince monk’) on a surimono print, which purportedly appeared in Hyūga Province,[50] The illustration here resembles an old man with bird-like body and nine legs.[20]

Similar yōkai

In Japanese folklore or popular imagination, there are also other similar yōkai that follow the pattern of predicting doom and instructing humans to copy or view its image, but lie outside the classification of amabie/amabiko according to a noted researcher. These are referred to generically as "other" yogenjū (予言獣).[51]

Among the other prophetic beasts was the arie (アリエ), which appeared in "Aotori-kōri" county, Higo Province, according to the Kōfu Nichinichi Shimbun[lower-alpha 14] newspaper dated 17 June 1876, although this report has been debunked by another paper.[lower-alpha 15][53]

The yamawarawa in the folklore of Amakusa is believed to haunt the mountains. Although neither of these last two emerge from sea, other similarities such as prophesying and three-leggedness indicate some sort of interrelationship.[2][4][54]

There are various other yōkai creatures that are vastly different in appearance, but have the ability to predict, such as the kudan,[55] the jinjahime[56] or "shrine princess", the hōnen game (豊年亀) or "bumper crop year turtle", and the "turtle woman".[57][2]

A tradition in the West ascribes every creature of the sea with the ability to foretell the future, and there is no scarcity of European legends about merfolk bringing prophecy. For this reason, the amabie is considered to be a type of mermaid, in some quarters. But since the amabie is credited with the ability to repel pestilence as well, it should be considered as more of a deity according to some.[58]

COVID-19

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan, amabie became a popular topic on Twitter in Japan. Manga artists (e.g. Chica Umino, Mari Okazaki and Toshinao Aoki) published their cartoon versions of amabie on social networks.[60] The Twitter account of Orochi Do, an art shop specializing in hanging scrolls of yōkai, is said to have been the first, tweeting "a new coronavirus countermeasure" in late February 2020.[61] A twitter bot account (amabie14) has been collecting images of amabie since March 2020.[62] This trend was noticed by scholars.[63][64][65]

See also

- Ningyo

- Fiji mermaid

- Jenny Haniver

- Cradleboard, which some amabie resemble

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Murakami (2000) reads "six months from the current year (当年より六ヶ月)" (quoted in Nagano (2005), p. 4), but Nagano (2005), p. 25 prints the entire text and reads "six years from the current year (當年より六ヶ年)".

- ↑ The Japanese letters ko (コ) and e (エ) being nearly interchangeably similar.

- ↑ The remainder is a source that does not recount detail on the Amahiko Nyūdo[?] (天彦入道) "charms (majinai)" he is referring to, except that these were pasted at the door around the time of the Satsuma Rebellion (1877) in the environs of Hiraka, Akita where the local historian author is native. The source is the book Yasoō danwa (八十翁談話) written by a local man named Denichirō Terada.[15]

- ↑ The leaf is bound along with unrelated material in the Tsubokawa manuscript (坪川本), now in the possession of the Fukui Prefectural Library (福井県立図書館). The painting was presumably by the known copyist, who was not born 1846, sot the 1844 date cannot be the date he painted it, but rather the date indicated on the original exemplar.[31]

- ↑ The specific example being Ame-no-wakahiko (天若日子) named in Japan's ancient pseudo-historical chronicles (kiki, i.e. Kojiki and Nihon Shoki.

- ↑ "Shinji-gun" is a possible pronunciation for both forms given, but not verifiable since the phonetics are not provided. The character Japanese: 郡 here is the same as the character pronounced "kōri" in another example.[41]

- ↑ Another nonexistent county in Higo Province is Aonuma-kōri (青沼郡/あほぬまこほり), with a nonexistence beach Isono-hama (磯野浜) named as the amahiko (尼彦/あまひこ nun prince) sighting spot by various "other newspapers" according to the Nagano Shinbun.[41]

- ↑ "Hikozaemon" in the hand-painted copy. Goroemon in the newspaper transcripts, Gorozaemon in the encyclopedia.

- ↑ Due to its mention of Kumamoto Prefecture.

- ↑ Note that the furigana actually reads amahima (あまひま) in Nagano's transcription, but a misprint there is assumed.

- ↑ The pamphlets themselves obtained by the newspaper are not known to have survived, and does not give a date in the passage quoted in the newspaper, but Nagano writes that the reporting was current.[32] The newspaper claimed the pamphlets were replicas of pamphlets distributed during the cholera epidemic of 1858 (Ansei 5), with the text matching identically, and researcher Nagano accepts this earlier date of provenance.[46]

- ↑ The pamphlets are identified as surimono (刷物) in the newspaper, which added they were about the size of a quartered hanshi size, i.e., very roughly a quartered legal size paper as discussed in note above. Also the newspaper reprinted a normalized text mixed with kanji, revealing that the original was entirely in kana.

- ↑ Compare with Amabie which made only a 6-year forecast.

- ↑ Now the Yamanashi Nichinichi Shimbun.

- ↑ The county by the name of "Aoshima-gun" does not exist there and the news was pronounced "fanciful" by the Nagano Shimbun dated 30 June 1876.[52]

Citations

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 24, 4–6.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Yumoto, Kōichi (2005) (in ja). Nihon genjū zusetsu. Kawaide Shobo. pp. 71–88. ISBN 978-4-309-22431-2.

- ↑ Iwama, Riki (5 June 2020). "Amabie no shōtai wo otte (1): sugata mita mono, shi wo nogare rareru amabiko no hakken / Fukui". 毎日新聞. https://mainichi.jp/articles/20200605/ddl/k18/040/220000c.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Yumoto (1999), pp. 178–180.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 6, 4.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 5.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Nagano (2005), p. 5, nine examples (incl. amabie) collated by the different ways in which names are written, on p. 7.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Amabiko[?] (あま彦). Mizuno Masanobu ed., Seisō kibun 青窓紀聞, Book 28, apud Nagano (2009), pp. 136–137

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Mozume Takami, "(Kechō) Amabiko", Kōbunko (Kōbunko kankōkai) 1: p. 1151, https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/969095/606 Facsimile illustration and text from the Nagasaki kai'i shokan no utsushi 35.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "Taishō jidai wa 'amabiko'? Hyakkajiten ni amabie ni nita yōkai, Tochigi Ashikaga Gakko de tenji". Mainichi Shimbun. 3 June 2020. https://mainichi.jp/articles/20200603/k00/00m/040/148000c.(The Kōbunko example)

- ↑ "Kocchi ga ganso? Yamai-yoke yōkai amabie: Fukui de Edo-ki no shiryō hakken". Mainichi Shimbun. 3 June 2020. https://mainichi.jp/articles/20200602/k00/00m/040/292000c.(金森穣家本『雑書留』の「あま彦」。越前市武生公会堂記念館蔵)

- ↑ Several more attestations were noted post-2005: a copy of Ambabiko[?] dated 1843 in Seisō kibun,[8] the facsimile and text of a different 1843 copy in an encyclopedia Kōbunko,[9][10] and an 1844 dated copy preserved in Echizen city.[11]

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 7, 8, 9.

- ↑ Nagano's 2005 paper considered the 1844 copy of the amabiko (‘sea prince’) to be the oldest,[13] but the 1843 copy in Nagano's 2009 essay[8] predates it, as well as the 1843 copy recorded in the encyclopedia.[9][10]

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 6, 25 and note (26).

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 8.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 13, 5–6.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 5–6, 12–13.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Nagano (2005), p. 7.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Nagano (2005), p. 6.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 21.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Nagano (2005), pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Nagano (2005) states that out of the 9 examples of amabiko/amabie,[19] the pictorial representation is available for 5, but since actually includes amabie as evident from his subsequent commentary re leg-number classification,[20] the total number of pictures is 6.[21] Two are depicted as quadrupeds (Amahiko-no-Mikoto and hand-painted Amahiko 'nun prince'), three are 3-legged or 3-finned ('sea prince', amabie, and Amahiko (Nagano Shinbun)), and one instance of 9-legged (amahiko-nyūdō, print).[22] On these paintings and prints, body hair and facial/head hair growth pattern also exhibit discrepancies.[22]。

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 3, the exact wording is not "toro-less", but "as if three long legs are growing immediately out of the head portion 頭部からいきなり長い三本足が生えたような".

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Amabie ni tsuzuke. Ekibyō fūjiru 'yogenjū' SNS de wadai. tori ya oni.. sugata ya katachi samazama" (in ja). Mainichi Shimbun. 7 June 2020. https://mainichi.jp/articles/20200606/k00/00m/040/118000c. (consults Eishū Nagano)

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Nagano (2005), p. 3.

- ↑ The text is supplied with furigana phonetics which literally reads amahiko, but still could be read as either "amahiko" or "amabiko".[26] (Since dakuten or sonorant marks are routinely eschewed in older texts). Nagano prefers the "amabiko" reading in his paper.

- ↑ Matsumoto, Yoshinosuke (1999). The Hotsuma Legends: Paths of the Ancestors: English translations on the Hotsuma tsutae. 2. Japan Translation Centre. p. 106. ISBN 9784931326019. https://books.google.com/books?id=agQRAQAAIAAJ&q=Umisachihiko.

- ↑ English rendition "sea prince" adapted from Umisachihiko translated as "Prince Luck of the Sea".[28] But hiko could be regarded as "man" or a common name like "Jack".

- ↑ Leaflet, as in written (and painted) on approximately a halved hanshi size (24 cm × 33 cm (9.45 in × 13.0 in)) paper,Nagano (2005), p. 1 i.e., very roughly a halved legal size paper.

- ↑ Nagano 2005, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Nagano (2005), p. 9.

- ↑ The leaflet is dated as the year of the dragon, and the text states it appeared on "this year of the dragon". This is an unusual case where the year of appearance is thus certain, because it is ambiguous in other examples.[32]

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 4–8 and fig. 2 on p. 21.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Tokyo Nichinichi Shinbun (8 August 1875), text sans title reprinted at Nagano (2005), p. 24. Cf. also Nagano (2005), pp. 6, 7.

- ↑ Iwama, Riki (6 June 2020). "Amabie no shōtai wo otte (2): ke no haeta yogenjū arawaru kaii samazama na amabiko / Fukui". 毎日新聞. https://mainichi.jp/articles/20200606/ddl/k18/040/173000c.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 13.

- ↑ Two examples for comparison noted earlier by Nagano,[37] plus the example in the Kōbunko encyclopedia.[9][10]

- ↑ Just Shinji[?] (眞字) in the encyclopedia.[9]

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 7 gave 眞字郡 for both examples; Nagano (2009), pp. 136, 148 emended the reading of the hand-painted example to 眞寺郡.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Nagano Shinbun (21 June 1876 [Meiji 9]), text sans title reprinted at Nagano (2005), p. 25. Cf. also Nagano (2005), pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 24.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 4–8, 24.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 4.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Yūbin Hōchi Shinbun (10 July 1882 [Meiji 15]), text sans title reprinted at Nagano (2005), p. 24. Cf. also Nagano (2005), pp. 6, 9, 13.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 9, 18.

- ↑ Tokyo Akebono Shinbun (東京曙新聞)(20 October 1881 [Meiji 14]), text sans title reprinted at Nagano (2005), p. 25. Cf. also Nagano (2005), pp. 7, 10.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 10.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 22.

- ↑ amahiko[?] nyūdō (尼彦入道) (surimono, also owned by Yumoto). Text reprinted as source #8 Nagano (2005), p. 25, illustration reproduced p. 22, fig. 7.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 8–9, 11–14. "others" charted on Table 2, on p. 23 (18 examples).

- ↑ Yumoto, Kōichi, ed (2001) (in ja). Chihō hatsu Meiji yōkai nyūsu. Kashiwa Shobo. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-4-7601-2089-5.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 8 and note (44).

- ↑ Nagano (2005), p. 12.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 9, 12.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 5, 9, 12, 20.

- ↑ Nagano (2005), pp. 8, 9, 12.

- ↑ Mizuki, Shigeru (1994) (in ja). Zusetsu yōkai taizen. Kodansha +α bunko. Kodansha. p. 50. ISBN 978-4-06-256049-8.

- ↑ 厚生労働省『STOP! 感染拡大――COVID-19』2020年。

- ↑ "Plague-predicting Japanese folklore creature resurfaces amid coronavirus chaos". Mainichi Daily News. 25 March 2020. https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20200325/p2a/00m/0na/021000c.

- ↑ Alt, Matt (9 April 2020). "From Japan, a Mascot for the Pandemic". New Yorker (New York). https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/from-japan-a-mascot-for-the-pandemic. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ↑ Kuhn, Anthony (22 April 2020). "In Japan, Mythical 'Amabie' Emerges from 19th Century Folklore to Fight COVID-19". https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/22/838323775/in-japan-mythical-amabie-emerges-from-19th-century-folklore-to-fight-covid-19.

- ↑ Furukawa, Yuki; Kansaku, Rei (2020). "Amabié—A Japanese Symbol of the COVID-19 Pandemic". JAMA 324 (6): 531–533. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12660. PMID 32678430.

- ↑ George, Sam (2020). "Amabie goes viral: the monstrous mercreature returns to battle the Gothic Covid-19". Critical Quarterly 62 (4): 32–40. doi:10.1111/criq.12579.

- ↑ Merli, Claudia (2020). "A chimeric being from Kyushu, Japan: Amabie's revival during Covid-19". Anthropology Today 36 (5): 6–10. doi:10.1111/1467-8322.12602. PMID 33041422.

Bibliography

- Murakami, Kenji, ed. (1999), Yōkai jiten, 毎日新聞社, pp. 23–24, ISBN 978-4-620-31428-0

- Nagano, Eishun (2005), "Yogenjū amabiko kō: amabiko wo tegakari ni", Jakuetsu Kyōdoshi Kenkyū (若越郷土研究) 49 (2): 1–30, https://karin21.flib.u-fukui.ac.jp/repo/JE49_2_279-1_nagano_cover._?key=DVCNBM, retrieved 7 January 2021

- Nagano, Eishun (2009), Komatsu, Kazuhiko, ed., "Yogenjū amabiko: saikō", Yōkai bunka kenkyū no saizensen (Serica Syobo): pp. 131–162, ISBN 978-4-7967-0291-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=sK5MAQAAIAAJ&q=%22アマビコ%22

- Yumoto, Kōichi (1999) (in ja). Meiji yōkai shimbun. Kashiwa Shobo. pp. 196–198. ISBN 978-4-7601-1785-7.

|