Social:Greenhushing

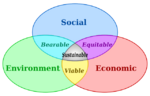

Greenhushing (sometimes called brownwashing or greenblushing) is the deliberate practice of under-reporting or withholding communication about an organization's corporate sustainability or environmental initiatives.[1] Unlike greenwashing, in which firms exaggerate or fabricate environmental claims, greenhushing occurs when organizations implement genuine sustainability measures but choose not to disclose them publicly.[2]

Companies may engage in greenhushing to protect legitimacy, avoid accusations of greenwashing, manage political risks, or limit scrutiny of their operations.[3]

Definition

Scholars define greenhushing as a form of "communication decoupling" in which the alignment between sustainability actions and disclosure is broken.[1] Whereas greenwashing involves making environmental claims not matched by practice, greenhushing involves genuine practices not matched by claims.[4]

Causes

Research identifies several drivers of greenhushing:

- Reputation management — avoiding accusations of hypocrisy or greenwashing by critics.[1]

- Regulatory and political uncertainty — especially amid ESG backlash in the United States, where more than 40 anti-ESG laws have been enacted since 2021.[5]

- Consumer skepticism — fear of the "green stigma," where eco-labeled products are seen as lower quality.[6]

- Industry dynamics — reluctance to raise benchmarks for entire sectors by publicizing advanced practices.[1]

- Altruistic or intrinsic motives — firms may act for social benefit without seeking recognition.[7]

Effects

Studies suggest that greenhushing can have negative consequences:

- Loss of competitive advantages such as product differentiation or regulatory goodwill.[8]

- Reduced transparency and information asymmetry for investors and consumers.[1]

A study from the Journal of Advertising Research found that lower sustainability levels are less transparent, thus providing hardly any signals to stakeholders.[9]

- Slowed industry-wide sustainability progress due to lack of shared best practices.[10]

Examples

Documented cases include:

- Tourism (UK) — rural businesses in the Peak District reported only 30% of their sustainability actions online, rarely mentioning climate change.[11]

- Hospitality (Europe) — hotels in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland that greenhushed were perceived less favorably by guests than those communicating openly.[12]

- Volunteer tourism (Indonesia) — operators in Yogyakarta found greenhushing more trustworthy among tourists compared to greenwashing.[13]

- Meat industry (Italy) — small and medium-sized enterprises engaged in sustainability practices but avoided formal reporting to reduce scrutiny.[14]

- Financial stability (China) — heavily polluting A-share listed companies implemented emission reduction strategies but deliberately avoided publicizing their environmental efforts because silence helped prevent their stock prices from crashing.[15]

Academic perspectives

Academics view greenhushing as a strategic response to institutional complexity. It has been described as:

- A form of institutional maintenance work, preserving legitimacy by limiting exposure.[1]

- Institutional repair work, where firms reduce transparency to protect sustainability practices amid ESG backlash.

Social Media and Greenhushing

Social media plays a role in how industries engage in greenhushing. A 2025 study analyzed the social media activity of UK hotels to uncover subtle greenhushing tactics. They discovered that “only 1.5% of Facebook posts and 1.8% of Instagram posts” addressed sustainability. They also reported lower engagement with sustainability posts compared to non-sustainability posts, suggesting that engagement level reflects user feedback on sustainability initiatives by these hotels.[16]

Another study utilizing large-scale observational data from X showed a similar result. It was found that corporate sustainability communications on social media are associated with an 29.11% decrease in engagement volume across companies’ regular communications.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Hilton, Joshua (2025). "An integrated analysis of greenhush". Innovation and Green Development 4. doi:10.1016/j.igd.2025.100222.

- ↑ Carlos, William C.; Lewis, Brian W. (2018). "Strategic silence: Withholding certification status as a hypocrite avoidance tactic". Administrative Science Quarterly 63 (1): 130–169. doi:10.1177/0001839217695089.

- ↑ Kim, E. Han; Lyon, Thomas P. (2015). "Greenwash vs. brownwash: Exaggeration and underreporting of corporate sustainability". Organization Science 26 (3): 705–723. doi:10.1287/orsc.2014.0949.

- ↑ Delmas, Magali A.; Burbano, Vanessa Cuerel (2011). "The drivers of greenwashing". California Management Review 54 (1): 64–87. doi:10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64.

- ↑ Rives, Tom (2024). "The politics of ESG backlash". Oxford Analytica.

- ↑ Luchs, Michael G.; Naylor, Rebecca Walker; Irwin, Julie R.; Raghunathan, Rajagopal (2010). "The sustainability liability: Potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference". Journal of Marketing 74 (5): 18–31. doi:10.1509/jmkg.74.5.18.

- ↑ Graafland, Johan; Mazereeuw-van der Duijn Schouten, Corrie (2012). "Motives for corporate social responsibility". Journal of Business Ethics 104 (4): 537–553. doi:10.1007/s10645-012-9198-5.

- ↑ Testa, Francesco; Boiral, Olivier; Iraldo, Fabio (2018). "Internalization of environmental practices and institutional complexity: Can stakeholders influence greenhushing?". Business Strategy and the Environment 27 (8): 1420–1432. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2960-2.

- ↑ Khan, Nayla; Nieto-García, Marta; Acuti, Diletta; Viglia, Giampaolo. "An Investigation of How and Why Organizations Enact Greenhushing". Journal of Advertising Research 0 (0): 1–24. doi:10.1080/00218499.2025.2514889. ISSN 0021-8499. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218499.2025.2514889.

- ↑ Donate, Mario J.; González-Mohíno, Manuel; Appio, Francesco Paolo; Bernhard, Fabian (2022). "Dealing with knowledge hiding to improve innovation capabilities in the hotel industry". Journal of Business Research 144: 572–586. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.02.001.

- ↑ Font, Xavier; Elgammal, Iman; Lamond, Ian (2017). "Greenhushing: The deliberate under communicating of sustainability practices by tourism businesses". Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25 (7): 1003–1025. doi:10.1080/09669582.2016.1158829.

- ↑ Ettinger, Alexander; Grabner-Kräuter, Sonja; Okazaki, Shintaro; Terlutter, Ralf (2021). "The desirability of CSR communication versus greenhushing in the hospitality industry". Journal of Travel Research 60 (3): 618–638. doi:10.1177/0047287520930087.

- ↑ Swestiana, Ika; Setyawan, Tri (2022). "Greenwashing or Greenhushing?: A Quasi-Experiment to Correlate Green Behaviour and Tourist’s Level of Trust Toward Communication Strategies in Volunteer Tourism’s Website". Tourism Management Perspectives 44: 101015. doi:10.34013/jk.v6i1.348.

- ↑ Galli, Francesca; Bonadonna, Alessandro (2023). "Sustainability performance and sustainability reporting in SMEs: a love affair or a fight?". Sustainability 15 (4): 2231. doi:10.1017/jmo.2023.40.

- ↑ Cheng, Hongwei; Dong, Dingrui; Feng, Yi (2024). "Corporate greenhushing and stock price crash risk: evidence from China". Environment, Development and Sustainability: 1-37. doi:10.1007/s10668-024-04935-5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380321415_Corporate_greenhushing_and_stock_price_crash_risk_evidence_from_China.

- ↑ Khan, Nayla; Nieto-García, Marta; Acuti, Diletta; Viglia, Giampaolo. "An Investigation of How and Why Organizations Enact Greenhushing". Journal of Advertising Research 0 (0): 1–24. doi:10.1080/00218499.2025.2514889. ISSN 0021-8499. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218499.2025.2514889.

- ↑ Tao, Yanda; Changseung, Yoo; Animesh, Animesh (16 October 2025). "Green Disclosure or Green Hushing? The Impact of Corporate Environmental Sustainability Communication on Social Media Engagement". Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5586951. Retrieved 3 November 2025.

|