Social:Natural resource management

Natural resource management (NRM) is the management of natural resources such as land, water, soil, plants and animals, with a particular focus on how management affects the quality of life for both present and future generations (stewardship).

Natural resource management deals with managing the way in which people and natural landscapes interact. It brings together natural heritage management, land use planning, water management, bio-diversity conservation, and the future sustainability of industries like agriculture, mining, tourism, fisheries and forestry. It recognizes that people and their livelihoods rely on the health and productivity of our landscapes, and their actions as stewards of the land play a critical role in maintaining this health and productivity.[1]

Natural resource management specifically focuses on a scientific and technical understanding of resources and ecology and the Life-supporting capacity of those resources.[2] Environmental management is similar to natural resource management. In academic contexts, the sociology of natural resources is closely related to, but distinct from, natural resource management.

History

The emphasis on a sustainability can be traced back to early attempts to understand the ecological nature of North American rangelands in the late 19th century, and the resource conservation movement of the same time.[3][4] This type of analysis coalesced in the 20th century with recognition that preservationist conservation strategies had not been effective in halting the decline of natural resources. A more integrated approach was implemented recognising the intertwined social, cultural, economic and political aspects of resource management.[5] A more holistic, national and even global form evolved, from the Brundtland Commission and the advocacy of sustainable development.

In 2005 the government of New South Wales, Australia established a Standard for Quality Natural Resource Management,[6] to improve the consistency of practice, based on an adaptive management approach.

In the United States, the most active areas of natural resource management are fisheries management,[7] wildlife management,[8] often associated with ecotourism and rangeland management, and forest management.[9] In Australia, water sharing, such as the Murray Darling Basin Plan and catchment management are also significant.

Ownership regimes

Natural resource management approaches [10] can be categorised according to the kind and right of stakeholders, natural resources:

- State property: Ownership and control over the use of resources is in hands of the state. Individuals or groups may be able to make use of the resources, but only at the permission of the state. National forest, National parks and military reservations are some US examples.

- Private property: Any property owned by a defined individual or corporate entity. Both the benefit and duties to the resources fall to the owner(s). Private land is the most common example.

- Common property: It is a private property of a group. The group may vary in size, nature and internal structure e.g. indigenous neighbours of village. Some examples of common property are community forests.

- Non-property (open access): There is no definite owner of these properties. Each potential user has equal ability to use it as they wish. These areas are the most exploited. It is said that "Nobody's property is Everybody's property". An example is a lake fishery. Common land may exist without ownership, in which case in the UK it is vested in a local authority.

- Hybrid: Many ownership regimes governing natural resources will contain parts of more than one of the regimes described above, so natural resource managers need to consider the impact of hybrid regimes. An example of such a hybrid is native vegetation management in NSW, Australia, where legislation recognises a public interest in the preservation of native vegetation, but where most native vegetation exists on private land.[11]

Stakeholder analysis

Stakeholder analysis originated from business management practices and has been incorporated into natural resource management in ever growing popularity. Stakeholder analysis in the context of natural resource management identifies distinctive interest groups affected in the utilisation and conservation of natural resources.[12]

There is no definitive definition of a stakeholder as illustrated in the table below. Especially in natural resource management as it is difficult to determine who has a stake and this will differ according to each potential stakeholder.[13]

Different approaches to who is a stakeholder:[13]

| Source | Who is a stakeholder | Kind of research |

|---|---|---|

| Freeman.[14] | "can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization's objectives" | Business Management |

| Bowie[15] | "without whose support the organization would cease to exist" | Business Management |

| Clarkson[16] | "... persons or groups that have, or claim, ownership, rights, or interests in a corporation and its activities, past, present, or future." | Business Management |

| Grimble and Wellard[17] | "...any group of people, organized or unorganized, who share a common interest or stake in a particular issue or system..." | Natural resource management |

| Gass et al.[18] | "... any individual, group and institution who would potentially be affected, whether positively or negatively, by a specified event, process or change." | Natural resource management |

| Buanes et al[19] | "... any group or individual who may directly or indirectly affect—or be affected—...planning to be at least potential stakeholders." | Natural resource management |

| Brugha and Varvasovszky[20] | "... stakeholders (individuals, groups and organizations) who have an interest (stake) and the potential to influence the actions and aims of an organization, project or policy direction." | Health policy |

| ODA[21] | "... persons, groups or institutions with interests in a project or programme." | Development |

Therefore, it is dependent upon the circumstances of the stakeholders involved with natural resource as to which definition and subsequent theory is utilised.

Billgrena and Holme[13] identified the aims of stakeholder analysis in natural resource management:

- Identify and categorise the stakeholders that may have influence

- Develop an understanding of why changes occur

- Establish who can make changes happen

- How to best manage natural resources

This gives transparency and clarity to policy making allowing stakeholders to recognise conflicts of interest and facilitate resolutions.[13][22] There are numerous stakeholder theories such as Mitchell et al.[23] however Grimble[22] created a framework of stages for a Stakeholder Analysis in natural resource management. Grimble[22] designed this framework to ensure that the analysis is specific to the essential aspects of natural resource management.

Stages in Stakeholder analysis:[22]

- Clarify objectives of the analysis

- Place issues in a systems context

- Identify decision-makers and stakeholders

- Investigate stakeholder interests and agendas

- Investigate patterns of inter-action and dependence (e.g. conflicts and compatibilities, trade-offs and synergies)

Application:

Grimble and Wellard[17] established that Stakeholder analysis in natural resource management is most relevant where issued can be characterised as;

- Cross-cutting systems and stakeholder interests

- Multiple uses and users of the resource.

- Market failure

- Subtractability and temporal trade-offs

- Unclear or open-access property rights

- Untraded products and services

- Poverty and under-representation[17][22]

Case studies:

In the case of the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, a comprehensive stakeholder analysis would have been relevant and the Batwa people would have potentially been acknowledged as stakeholders preventing the loss of people's livelihoods and loss of life.[17][22]

File:Natural Resource Management in Wales - 5 May 2015.webm In Wales, Natural Resources Wales, a Welsh Government sponsored body "pursues sustainable management of natural resources" and "applies the principles of sustainable management of natural resources" as stated in the Environment (Wales) Act 2016.[24] NRW is responsible for more than 40 different types of regulatory regime across a wide range of activities.

Nepal, Indonesia and Koreas' community forestry are successful examples of how stakeholder analysis can be incorporated into the management of natural resources. This allowed the stakeholders to identify their needs and level of involvement with the forests.

Criticisms:

- Natural resource management stakeholder analysis tends to include too many stakeholders which can create problems in of its self as suggested by Clarkson. "Stakeholder theory should not be used to weave a basket big enough to hold the world's misery."[25]

- Starik[26] proposed that nature needs to be represented as stakeholder. However this has been rejected by many scholars as it would be difficult to find appropriate representation and this representation could also be disputed by other stakeholders causing further issues.[13]

- Stakeholder analysis can be used exploited and abused in order to marginalise other stakeholders.[12]

- Identifying the relevant stakeholders for participatory processes is complex as certain stakeholder groups may have been excluded from previous decisions.[27]

- On-going conflicts and lack of trust between stakeholders can prevent compromise and resolutions.[27]

Alternatives/ Complementary forms of analysis:

- Social network analysis

- Common pool resource

Management of the resources

Natural resource management issues are inherently complex and contentious. First, they involve the ecological cycles, hydrological cycles, climate, animals, plants and geography, etc. All these are dynamic and inter-related. A change in one of them may have far reaching and/or long term impacts which may even be irreversible. Second, in addition to the complexity of the natural systems, managers also have to consider various stakeholders and their interests, policies, politics, geographical boundaries and economic implications. It is impossible to fully satisfy all aspects at the same time. Therefore, between the scientific complexity and the diverse stakeholders, natural resource management is typically contentious.

After the United Nations Conference for the Environment and Development (UNCED) held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992,[28] most nations subscribed to new principles for the integrated management of land, water, and forests. Although program names vary from nation to nation, all express similar aims.

The various approaches applied to natural resource management include:

- Top-down (command and control)

- Community-based natural resource management

- Adaptive management

- Precautionary approach

- Integrated natural resource management

- Ecosystem management

Community-based natural resource management

The community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) approach combines conservation objectives with the generation of economic benefits for rural communities. The three key assumptions being that: locals are better placed to conserve natural resources, people will conserve a resource only if benefits exceed the costs of conservation, and people will conserve a resource that is linked directly to their quality of life.[5] When a local people's quality of life is enhanced, their efforts and commitment to ensure the future well-being of the resource are also enhanced.[29] Regional and community based natural resource management is also based on the principle of subsidiarity. The United Nations advocates CBNRM in the Convention on Biodiversity and the Convention to Combat Desertification. Unless clearly defined, decentralised NRM can result in an ambiguous socio-legal environment with local communities racing to exploit natural resources while they can, such as the forest communities in central Kalimantan (Indonesia).[30]

A problem of CBNRM is the difficulty of reconciling and harmonising the objectives of socioeconomic development, biodiversity protection and sustainable resource utilisation.[31] The concept and conflicting interests of CBNRM,[32][33] show how the motives behind the participation are differentiated as either people-centred (active or participatory results that are truly empowering)[34] or planner-centred (nominal and results in passive recipients). Understanding power relations is crucial to the success of community based NRM. Locals may be reluctant to challenge government recommendations for fear of losing promised benefits.

CBNRM is based particularly on advocacy by nongovernmental organizations working with local groups and communities, on the one hand, and national and transnational organizations, on the other, to build and extend new versions of environmental and social advocacy that link social justice and environmental management agendas[35] with both direct and indirect benefits observed including a share of revenues, employment, diversification of livelihoods and increased pride and identity. Ecological and societal successes and failures of CBNRM projects have been documented.[36][37] CBNRM has raised new challenges, as concepts of community, territory, conservation, and indigenous are worked into politically varied plans and programs in disparate sites. Warner and Jones[38] address strategies for effectively managing conflict in CBNRM.

The capacity of Indigenous communities to conserve natural resources has been acknowledged by the Australian Government with the Caring for Country[39] Program. Caring for our Country is an Australian Government initiative jointly administered by the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry and the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. These Departments share responsibility for delivery of the Australian Government's environment and sustainable agriculture programs, which have traditionally been broadly referred to under the banner of 'natural resource management'. These programs have been delivered regionally, through 56 State government bodies, successfully allowing regional communities to decide the natural resource priorities for their regions.[40]

More broadly, a research study based in Tanzania and the Pacific researched what motivates communities to adopt CBNRM's and found that aspects of the specific CBNRM program, of the community that has adopted the program, and of the broader social-ecological context together shape the why CBNRM's are adopted.[41] However, overall, program adoption seemed to mirror the relative advantage of CBNRM programs to local villagers and villager access to external technical assistance.[41] There have been socioeconomic critiques of CBNRM in Africa,[42] but ecological effectiveness of CBNRM measured by wildlife population densities has been shown repeatedly in Tanzania.[43][44]

Governance is seen as a key consideration for delivering community-based or regional natural resource management. In the State of NSW, the 13 catchment management authorities (CMAs) are overseen by the Natural Resources Commission (NRC), responsible for undertaking audits of the effectiveness of regional natural resource management programs.[45]

Criticisms of Community-Based Natural Resource Management

Though presenting a transformative approach to resource management that recognizes and involves local communities rather than displacing them, Community-Based Natural Resource Management strategies have faced scrutiny from both scholars and advocates for indigenous communities. Tania Murray, in her examination of CBNRM in Upland Southeast Asia,[46] discovered certain limitations associated with the strategy, primarily stemming from her observation of an idealistic perspective of the communities held by external entities implementing CBNRM programs.

Murray's findings revealed that, in the Uplands, CBNRM as a legal strategy imposed constraints on the communities. One significant limitation was the necessity for communities to fulfill discriminatory and enforceable prerequisites in order to obtain legal entitlements to resources. Murray contends that such legal practices, grounded in specific distinguishing identities or practices, pose a risk of perpetuating and strengthening discriminatory norms in the region.[46]

Furthermore, adopting a Marxist perspective centered on class struggle, some have criticized CBNRM as an empowerment tool, asserting that its focus on state-community alliances may limit its effectiveness, particularly for communities facing challenges from "vicious states," thereby restricting the empowerment potential of the programs.[46]

Gender-based natural resource management

Social capital and gender are factors that impact community-based natural resource management (CBNRM), including conservation strategies and collaborations between community members and staff. Through three months of participant observation in a fishing camp in San Evaristo, Mexico, Ben Siegelman learned that the fishermen build trust through jokes and fabrications. He emphasizes social capital as a process because it is built and accumulated through practice of intricate social norms. Siegelman notes that playful joking is connected to masculinity and often excludes women. He stresses that both gender and social capital are performed. Furthermore, in San Evaristo, the gendered network of fishermen is simultaneously a social network. Nearly all fishermen in San Evaristo are men and most families have lived there for generations. Men form intimate relationships by spending 14 hour work days together, while women spend time with the family managing domestic caretaking. Siegelman observes three categories of lies amongst the fishermen: exaggerations, deceptions, and jokes. For example a fisherman may exaggerate his success fishing at a particular spot to mislead friends, place his hand on the scale to turn a larger profit, or make a sexual joke to earn respect. As Siegelman puts it, "lies build trust." Siegelman saw that this division of labor was reproduced, at least in part, to do with the fact that the culture of lying and trust was a masculine activity unique to the fisherman. Similar to the ways in which the culture of lying excluded women from the social sphere of fishing, conservationists were also excluded from this social arrangement and, thus, were not able to obtain the trust needed to do their work of regulating fishing practices. As outsiders, conservationists, even male conservationists, were not able to fit the ideal of masculinity that was considered "trustable" by the fishermen and could convince them to implement or participate in conservation practices. In one instance, the researcher replied jokingly "in the sea" when a fisherman asked where the others were fishing that day. This vague response earned him trust. Women are excluded from this form of social capital because many of the jokes center around "masculine exploits". Siegelman finishes by asking: how can female conservationists act when they are excluded through social capital? What role should men play in this situation?[47]

Adaptive Management

The primary methodological approach adopted by catchment management authorities (CMAs) for regional natural resource management in Australia is adaptive management.[6]

This approach includes recognition that adaption occurs through a process of 'plan-do-review-act'. It also recognises seven key components that should be considered for quality natural resource management practice:

- Determination of scale

- Collection and use of knowledge

- Information management

- Monitoring and evaluation

- Risk management

- Community engagement

- Opportunities for collaboration.[6]

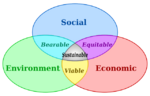

Integrated natural resource management

Integrated natural resource management (INRM) is the process of managing natural resources in a systematic way, which includes multiple aspects of natural resource use (biophysical, socio-political, and economic) meet production goals of producers and other direct users (e.g., food security, profitability, risk aversion) as well as goals of the wider community (e.g., poverty alleviation, welfare of future generations, environmental conservation). It focuses on sustainability and at the same time tries to incorporate all possible stakeholders from the planning level itself, reducing possible future conflicts. The conceptual basis of INRM has evolved in recent years through the convergence of research in diverse areas such as sustainable land use, participatory planning, integrated watershed management, and adaptive management.[48][49] INRM is being used extensively and been successful in regional and community based natural management.[50]

Frameworks and modelling

There are various frameworks and computer models developed to assist natural resource management.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

GIS is a powerful analytical tool as it is capable of overlaying datasets to identify links. A bush regeneration scheme can be informed by the overlay of rainfall, cleared land and erosion.[51] In Australia, Metadata Directories such as NDAR provide data on Australian natural resources such as vegetation, fisheries, soils and water.[52] These are limited by the potential for subjective input and data manipulation.

Natural Resources Management Audit Frameworks

The NSW Government in Australia has published an audit framework[53] for natural resource management, to assist the establishment of a performance audit role in the governance of regional natural resource management. This audit framework builds from other established audit methodologies, including performance audit, environmental audit and internal audit. Audits undertaken using this framework have provided confidence to stakeholders, identified areas for improvement and described policy expectations for the general public.[54][55]

The Australian Government has established a framework for auditing greenhouse emissions and energy reporting, which closely follows Australian Standards for Assurance Engagements.

The Australian Government is also currently preparing an audit framework for auditing water management, focussing on the implementation of the Murray Darling Basin Plan.

Other elements

- Biodiversity Conservation

The issue of biodiversity conservation is regarded as an important element in natural resource management. What is biodiversity? Biodiversity is a comprehensive concept, which is a description of the extent of natural diversity. Gaston and Spicer[56] (p. 3) point out that biodiversity is "the variety of life" and relate to different kinds of "biodiversity organization". According to Gray[57] (p. 154), the first widespread use of the definition of biodiversity, was put forward by the United Nations in 1992, involving different aspects of biological diversity.

- Precautionary Biodiversity Management

The "threats" wreaking havoc on biodiversity include; habitat fragmentation, putting a strain on the already stretched biological resources; forest deterioration and deforestation; the invasion of "alien species" and "climate change"[58]( p. 2). Since these threats have received increasing attention from environmentalists and the public, the precautionary management of biodiversity becomes an important part of natural resources management. According to Cooney, there are material measures to carry out precautionary management of biodiversity in natural resource management.

- Concrete "policy tools"

Cooney claims that the policy making is dependent on "evidences", relating to "high standard of proof", the forbidding of special "activities" and "information and monitoring requirements". Before making the policy of precaution, categorical evidence is needed. When the potential menace of "activities" is regarded as a critical and "irreversible" endangerment, these "activities" should be forbidden. For example, since explosives and toxicants will have serious consequences to endanger human and natural environment, the South Africa Marine Living Resources Act promulgated a series of policies on completely forbidding to "catch fish" by using explosives and toxicants.

- Administration and guidelines

According to Cooney, there are four methods to manage the precaution of biodiversity in natural resources management;

- "Ecosystem-based management" including "more risk-averse and precautionary management", where "given prevailing uncertainty regarding ecosystem structure, function, and inter-specific interactions, precaution demands an ecosystem rather than single-species approach to management".[59]

- "Adaptive management" is "a management approach that expressly tackles the uncertainty and dynamism of complex systems".

- "Environmental impact assessment" and exposure ratings decrease the "uncertainties" of precaution, even though it has deficiencies, and

- "Protectionist approaches", which "most frequently links to" biodiversity conservation in natural resources management.

- Land management

In order to have a sustainable environment, understanding and using appropriate management strategies is important. In terms of understanding, Young[60] emphasises some important points of land management:

- Comprehending the processes of nature including ecosystem, water, soils

- Using appropriate and adapting management systems in local situations

- Cooperation between scientists who have knowledge and resources and local people who have knowledge and skills

Dale et al. (2000)[61] study has shown that there are five fundamental and helpful ecological principles for the land manager and people who need them. The ecological principles relate to time, place, species, disturbance and the landscape and they interact in many ways. It is suggested that land managers could follow these guidelines:

- Examine impacts of local decisions in a regional context, and the effects on natural resources.

- Plan for long-term change and unexpected events.

- Preserve rare landscape elements and associated species.

- Avoid land uses that deplete natural resources.

- Retain large contiguous or connected areas that contain critical habitats.

- Minimize the introduction and spread of non-native species.

- Avoid or compensate for the effects of development on ecological processes.

- Implement land-use and land-management practices that are compatible with the natural potential of the area.

See also

- Agriculture

- Agroecology

- Biodiversity

- Bioregion

- Conservation biology

- Conservation movement

- Conservation reliant species

- Cultural resource management

- Deep ecology

- Earth science

- Ecology

- Ecosystem management

- Ecology movement

- Ecosystem

- Environmental movement

- Environmental organizations

- Environmental protection

- Environmental resources management

- Forestry

- Global warming

- Habitat conservation

- Holistic management

- List of environmental issues

- Natural capital

- Natural environment

- Natural heritage

- Natural resource

- Nature

- Recycling

- Renewable energy

- Renewable resource

- Stewardship

- Sustainable agriculture

- Sustainable management

References

- ↑ "Resilient landscapes and communities managing natural resources in New South Wales". Nrc.nsw.gov.au. http://nrc.nsw.gov.au/content/documents/Brochure%20-%20Resilient%20landscapes.pdf.

- ↑ "Bachelor of Applied Science (Natural Resource Management)". Massey University. http://study.massey.ac.nz/massey/students/studymassey/programme.cfm?major_code=2261&prog_code=93013.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Berkeley University of California: Geography: Geog 175: Topics in the History of Natural Resource Management: Spring 2006: Rangelands

- ↑ San Francisco State University: Department of Geography: GEOG 657/ENVS 657: Natural Resource Management: Biotic Resources: Natural Resource Management and Environmental History

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Thakadu, O. T. (2005). "Success factors in community based natural resources management in northern Botswana: Lessons from practice". Natural Resources Forum 29 (3): 199–212. doi:10.1111/j.1477-8947.2005.00130.x. Bibcode: 2005NRF....29..199T.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 NSW Government 2005, Standard for Quality Natural Resource Management, NSW Natural Resources Commission, Sydney

- ↑ Hubert, Wayne A.; Quist, Michael C., eds (2010). Inland Fisheries Management in North America (Third ed.). Bethesda, MD: American Fisheries Society. p. 736. ISBN 978-1-934874-16-5.

- ↑ Bolen, Eric G.; Robinson, William L., eds (2002). Wildlife Ecology and Management (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. p. 634. ISBN 013066250X.

- ↑ Bettinger, Pete; Boston, Kevin; Siry, Jacek et al., eds (2017). Forest Management and Planning (Second ed.). Academic Press. p. 362. ISBN 9780128094761.

- ↑ Sikor, Thomas; He, Jun; Lestrelin, Guillaume (2017). "Property Rights Regimes and Natural Resources: A Conceptual Analysis Revisited". World Development 93: 337–349. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.12.032.

- ↑ "Native Vegetation Act 2003". Environment.nsw.gov.au. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/vegetation/nvact.htm.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Dandy, N. et al. (2009) ‘Who's in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management,’ Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 90, pp. 1933–1949

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Billgrena, C., Holme, H. (2008) ‘Approaching reality: Comparing stakeholder analysis and cultural theory in the context of natural resource management,’ Land Use Policy, vol. 25, pp. 550–562

- ↑ Freeman, E.R. (1999) ‘The politics of stakeholder theory: some further research directions,’ Business Ethics Quartley, vol. 4, Issue. 4, pp. 409–421

- ↑ Bowie, N. (1988) The moral obligations of multinational corporations. In: Luper-Foy (Ed.), Problems of International Justice. Boulder: Westview Press, pp. 97–113.

- ↑ Clarkson, M.B.E. (1995) ‘A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance,’ Academy of Management Review, vol. 20, Issue. 1, pp. 92–117

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Grimble, R., Wellard, K. (1997) ‘Stakeholder methodologies in natural resource management: a review of principles, contexts, experiences and opportunities.’ Agricultural Systems, vol. 55, Issue. 2, pp. 173–193

- ↑ Gass, G., Biggs, S., Kelly, A. (1997) ‘Stakeholders, science and decision making for poverty-focused rural mechanization research and development,’ World Development, vol. 25, Issue. 1, pp. 115–126

- ↑ Buanes, A., et al. (2004) ‘In whose interest? An exploratory analysis of stakeholders in Norwegian coastal zone planning,’ Ocean & Coastal Management, vol. 47, pp. 207–223

- ↑ Brugha, Ruairí; Varvasovszky, Zsuzsa (September 2000). "Stakeholder analysis: a review". Health Policy and Planning 15 (3): 239–246. doi:10.1093/heapol/15.3.239. PMID 11012397.

- ↑ ODA (July 1995). "Guidance note on how to do stakeholder analysis of aid projects and programmes". Overseas Development Administration, Social Development Department. https://sswm.info/sites/default/files/reference_attachments/ODA%201995%20Guidance%20Note%20on%20how%20to%20do%20a%20Stakeholder%20Analysis.pdf.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Grimble, R (1998). Stakeholder methodologies in natural resource management, Socioeconomic Methodologies. Chatham: Natural Resources Institute. pp. 1–12. http://www.nri.org/old/publications/bpg/bpg02.pdf. Retrieved 27 October 2014.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Mitchell, R. K. (1997). TOWARD A THEORY OF STAKEHOLDER IDENTIFICATION AND SALIENCE: DEFINING THE PRINCIPLE OF WHO AND WHAT REALLY COUNTS. 22. Academy of Management Review. pp. 853–886.

- ↑ "Environment (Wales) Act 2016. Part 1, Section 5". The National Archives. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/anaw/2016/3/section/5/enacted.

- ↑ Clarkson, M.B.E. (1994) A risk based model of stakeholder theory. Toronto: Working Paper, University of Toronto, pp.10

- ↑ Starik, M. (1995) ‘Should trees have managerial standing? Toward stakeholder status for non-human nature,’ Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 14, pp. 207–217

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Prell, C., et al. (2007) Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in Natural Resource Management. Leeds: Sustainability Research Institute, University of Leeds, pp. 1-21

- ↑ "United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3-14 June 1992". https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992.

- ↑ Ostrom, E, Schroeder, L and Wynne, S 1993. Institutional incentives and sustainable development: infrastructure policies in perspective. Westview Press. Oxford, UK. 266 pp.

- ↑ Bartley, T Andersson, K, Jager P and Van Laerhoven 2008 The contribution of Institutional Theories for explaining Decentralization of Natural Resource Governance. Society and Natural Resources, 21:160-174 doi:10.1080/08941920701617973

- ↑ Kellert, S; Mehta, J; Ebbin, S; Litchtenfeld, L. (2000). Community natural resource management: promise, rhetoric, and reality. Society and Natural Resources, 13:705-715. http://biologicalcapital.com/art/Article-%20Community%20Natural%20Resource%20Management.pdf. Retrieved 27 October 2014.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Brosius, J.; Peter Tsing; Anna Lowenhaupt; Zerner, Charles (1998). "Representing communities: Histories and politics of community-based natural resource management". Society & Natural Resources 11 (2): 157–168. doi:10.1080/08941929809381069. Bibcode: 1998SNatR..11..157B.

- ↑ Twyman, C 2000. Participatory Conservation? Community-based Natural Resource Management in Botswana. The Geographical Journal, Vol 166, No.4, December 2000, pp 323-335 doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2000.tb00034.x

- ↑ Measham TG (2007) Building capacity for environmental management: local knowledge and rehabilitation on the Gippsland red gum plains, Australian Geographer, Vol 38 issue 2, pp 145–159 doi:10.1080/00049180701392758

- ↑ Shackleton, S; Campbell, B; Wollenberg, E; Edmunds, D. (March 2002). Devolution and community-based natural resource management: creating space for local people to participate and benefit?. ODI, Natural Resource Perspectives. http://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/3646/76-devolution-community-based-natural-resource-management.pdf. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Brooks, Jeremy S.; Waylen, Kerry A.; Mulder, Monique Borgerhoff (2012-12-26). "How national context, project design, and local community characteristics influence success in community-based conservation projects" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (52): 21265–21270. doi:10.1073/pnas.1207141110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 23236173. Bibcode: 2012PNAS..10921265B.

- ↑ Lee, Derek E.; Bond, Monica L. (2018-04-03). "Quantifying the ecological success of a community-based wildlife conservation area in Tanzania" (in en). Journal of Mammalogy 99 (2): 459–464. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyy014. PMID 29867255.

- ↑ Warner, M; Jones, P (July 1998). Assessing the need to manage conflict in community-based natural resource projects. ODI Natural Resource Perspectives. http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/download/2117.pdf. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ "Caring for Country Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts". Australian Government. http://www.nrm.gov.au/nrm/index.html.

- ↑ "PROGRESS TOWARDS HEALTHY RESILIENT LANDSCAPES IMPLEMENTING THE STANDARD, TARGETS AND CATCHMENT ACTION PLANS". Nrc.nsw.gov.au. http://nrc.nsw.gov.au/content/documents/2010%20Progress%20report.pdf.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Mascia, Michael B.; Mills, Morena (2018). "When conservation goes viral: The diffusion of innovative biodiversity conservation policies and practices" (in en). Conservation Letters 11 (3): e12442. doi:10.1111/conl.12442. ISSN 1755-263X. Bibcode: 2018ConL...11E2442M.

- ↑ Bluwstein, Jevgeniy; Moyo, Francis; Kicheleri, Rose Peter (2016-07-01). "Austere Conservation: Understanding Conflicts over Resource Governance in Tanzanian Wildlife Management Areas" (in en). Conservation and Society 14 (3): 218. doi:10.4103/0972-4923.191156. http://www.conservationandsociety.org/article.asp?issn=0972-4923;year=2016;volume=14;issue=3;spage=218;epage=231;aulast=Bluwstein.

- ↑ Lee, Derek E. (2018-08-10). "Evaluating conservation effectiveness in a Tanzanian community wildlife management area" (in en). The Journal of Wildlife Management 82 (8): 1767–1774. doi:10.1002/jwmg.21549. ISSN 0022-541X. Bibcode: 2018JWMan..82.1767L. https://scholarsphere.psu.edu/resources/1910e1d7-35d1-4ae3-ae78-48c5c58f99aa.

- ↑ Lee, Derek E; Bond, Monica L (2018-02-26). "Quantifying the ecological success of a community-based wildlife conservation area in Tanzania" (in en). Journal of Mammalogy 99 (2): 459–464. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyy014. ISSN 0022-2372. PMID 29867255.

- ↑ "NSW Legislation". Legislation.nsw.gov.au. http://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/viewtop/inforce/act+102+2003+cd+0+N/?autoquery=%28Content%3D%28%28%22natural%22%20OR%20%22resources%22%20OR%20%22commission%22%29%29%29%20AND%20%28%28Type%3D%22act%22%20AND%20Repealed%3D%22N%22%29%20OR%20%28Type%3D%22subordleg%22%20AND%20Repealed%3D%22N%22%29%29&dq=Document%20Types%3D%22Acts,%20Regs%22,%20Any%20Words%3D%22natural%20resources%20commission%22,%20Search%20In%3D%22Text%22&fullquery=%28%28%28%22natural%22%20OR%20%22resources%22%20OR%20%22commission%22%29%29%29.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Murray, Tania (2002). "Engaging Simplifications: Community-Based Resource Management, Market Processes and State Agendas in Upland Southeast Asia". World Development 30 (2): 265–283. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00103-6.

- ↑ Siegelman, Ben (2019). ""Lies Build Trust": Social capital, masculinity, and community-based resource management in a Mexican fishery.". World Development 123: 104601. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.05.031.

- ↑ Lovell, C.; Mandondo A.; Moriarty P. (2002). "The question of scale in integrated natural resource management". Conservation Ecology 5 (2). doi:10.5751/ES-00347-050225.

- ↑ Holling C.S. and Meffe, G. K. 2002 'Command and control and the Pathology of Natural Resource Management. Conservation Biology. vol.10. issue 2. pages 328–337, April 1996

- ↑ ICARDA 2005, Sustainable agricultural development for marginal dry areas, International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, Aleppo, Syria

- ↑ Harding R., 1998, Environmental Decision-Making: The Role of Scientists, Engineers and the Public, Federation Press, Leichhardt. pp366.

- ↑ Hamilton, C and Attwater, R (1996) Usage of, and demand for Environmental Statistics in Australia, in Tracking Progress: Linking Environment and Economy Through Indicators and Accounting Systems Conference Papers, 1996 Australian Academy of Science Fenner Conference on the Environment, Institute of Environmental Studies, UNSW, Sydney, 30 September to 3 October 1996.

- ↑ "Framework for Auditing the Implementation of Catchment Action Plans". Nrc.nsw.gov.au. http://www.nrc.nsw.gov.au/content/documents/Audit%20framework.pdf.

- ↑ "MURRAY CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY : Audit Report". Nrc.nsw.gov.au. http://www.nrc.nsw.gov.au/content/documents/Audit%20report%20-%20Murray%202010.pdf.

- ↑ "Nature Audit". Nrc.nsw.gov.au. http://riskaudit.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Nature-audit-NZ-Accountants-Journal-March-2010.pdf.

- ↑ Gaston, KJ & Spicer, JI 2004, Biodiversity: An Introduction, Blackwell Publishing Company, Malden.

- ↑ Gray, JS (1997). Marine biodiversity: patterns, threats and conservation needs. http://bolt.lakeheadu.ca/~bpaynewww/CMR/marinebiod.pdf. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Cooney, R (2004). The Precautionary Principle in Biodiversity Conservation and Natural Resource Management. IUCN Policy and Global Change Series. http://pprinciple.net/publications/PrecautionaryPrincipleissuespaper.pdf. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Lackey, Robert (1998). "Seven pillars of ecosystem management". Landscape and Urban Planning 40 (1–3): 21–30. doi:10.1016/S0169-2046(97)00095-9. https://zenodo.org/record/1259923.

- ↑ Young, A 1998, Land resources: now and for the future, Cambridge University Press, UK

- ↑ Dale, VH, Brown, S, Hawuber, RA, Hobbs, NT, Huntly, Nj Naiman, RJ, Riebsame, WE, Turner, MG & Valone, TJ 2000, ‘Ecological guidelines for land use and management’, in Dale, VH & Hawuber, RA (eds), Applying ecological principles to land management, Springer-Verlag, NY

|