Social:Languages of the Roman Empire

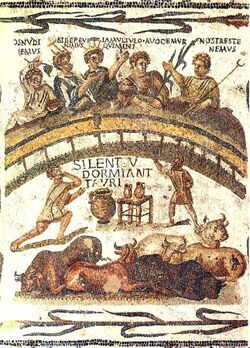

- "We're going to be naked" ([N]os nudi [f]iemus)

- "We're here to drink" (Bibere venimus)

- "you're all talking a lot" (Ia[m] multu[m] loquimini)

- "We may get called away" (Avocemur)

- "We're having three [glasses]." (Nos tres tenemus)

The scene may convey a proverbial expression equivalent to both "Let sleeping dogs lie" and "Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we may die"[1]

Latin and Greek were the dominant languages of the Roman Empire, but other languages were regionally important. Latin was the original language of the Romans and remained the language of imperial administration, legislation, and the military throughout the classical period.[2] In the West, it became the lingua franca and came to be used for even local administration of the cities including the law courts.[3][4] After all freeborn male inhabitants of the Empire were universally enfranchised in 212 AD, a great number of Roman citizens would have lacked Latin, though they were expected to acquire at least a token knowledge, and Latin remained a marker of "Romanness".[5]

After the conquests of Alexander the Great in late 4th century BCE, Koine Greek had become a shared language around the eastern Mediterranean and diplomatic communications in the East, even beyond the borders of the Empire. The international use of Greek was one condition that enabled the spread of Christianity, as indicated for example by the choice of Greek as the language of the New Testament in the Bible[6] and its use for the ecumenical councils of the Christian Roman Empire rather than Latin. With the dissolution of the Empire in the West, Greek became the more dominant language of the Roman Empire in the East, modernly referred to as the Byzantine Empire.

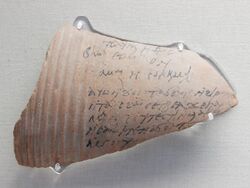

As the communication in ancient society was predominantly oral, it can be difficult to determine the extent to which regional or local languages continued to be spoken or used for other purposes under Roman rule. Some evidence exists in inscriptions, or in references in Greek and Roman texts to other languages and the need for interpreters. For Punic, Coptic, and Aramaic or Syriac, a significant amount of epigraphy or literature survives.[7] The Celtic languages were widespread throughout much of western Europe, and while the orality of Celtic education left scant written records,[8] Celtic epigraphy is limited in quantity but not rare.[9] The Germanic languages of the Empire have left next to no inscriptions or texts, with the exception of Gothic.[10] Multilingualism contributed to the "cultural triangulation" by means of which an individual who was neither Greek nor Roman might construct an identity through the processes of Romanization and Hellenization.[11]

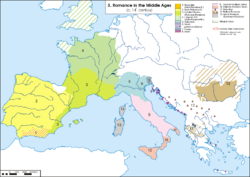

After the decentralization of political power in late antiquity, Latin developed locally in the Western provinces into branches that became the Romance languages, including Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Catalan, Occitan and Romanian. By the early 21st century, the first or second language of more than a billion people derived from Latin.[12] Latin itself remained an international medium of expression for diplomacy and for intellectual developments identified with Renaissance humanism up to the 17th century, and for law and the Roman Catholic Church to the present.

Latin

Latin was the language of the Romans from the earliest known period. Writing under the first Roman emperor Augustus, Virgil emphasizes that Latin was a source of Roman unity and tradition. In Virgil's epic Aeneid about the founding of Rome, the supreme deity Jupiter dictates that the refugee Trojans who have come to settle in Italy will use the language of the native Latini as a means of unification: "they will keep the speech (sermo) and mores of their fathers ... and I will make them all Latins with one mode of expression" (uno ore, literally "with one mouth").[13] The Julio-Claudian emperors, who claimed descent from the Virgilian hero Aeneas, encouraged high standards of correct Latin (Latinitas), a linguistic movement identified in modern terms as Classical Latin, and favored Latin for conducting official business.[14]

Latin became the language of conquered areas because local people started speaking it, and not because the population was displaced by Latin-speakers.[15] Latin was not imposed officially on peoples brought under Roman rule.[16] Saint Augustine observed that Romans preferred for Latin to be adopted per pacem societatis, through a social pact.[17] This language policy contrasts with that of Alexander, who aimed to impose Greek throughout his empire as the official language.[18] Latin was not a requirement for Roman citizenship, and there was no state-supported schooling that privileged it as the medium for education: fluency was desirable for its "high cultural, political, legal, social and economic value".[19]

Latin was needed for imperial service and advancement, and was the language used for the internal functioning of government.[20] Edicts and official communications of the emperor were in Latin, including rulings on local laws that might be in another language.[21]

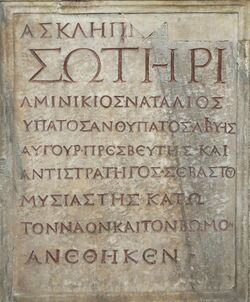

The Romans placed a high value on the written word, as indicated by their obsession with documentation and public inscriptions. The Imperial bureaucracy was so dependent on writing that the Babylonian Talmud (bT Shabbat 11a) declared "if all seas were ink, all reeds were pen, all skies parchment, and all men scribes, they would be unable to set down the full scope of the Roman government's concerns."[22] Estimates of the average literacy rate in the Empire range from 5 to 30 percent or higher, depending in part on the definition of "literacy".[23] The lack of state intervention in access to education was a barrier to literacy, since formal education was available only to children from families who could pay for it.[24]

The birth certificates and wills of Roman citizens had to be written in Latin until the time of Alexander Severus (reigned 222–235).[26] Illiterate Roman subjects would have someone such as a government scribe (scriba) read or write their official documents for them.[27] Laws and edicts were posted in writing as well as read out.[28] Public art and religious ceremonies were ways to communicate imperial ideology regardless of language spoken or ability to read.[29] An early form of story ballet (pantomimus) was brought to Rome by Greek performers and became popular throughout the multilingual empire in part because it relied on gesture rather than verbal expression.[30]

Latin was the official language of the Roman army until the mid-6th century, and remained the most common language for military use even in the Eastern empire until the 630s.[31] By contrast, only two bishops are known to have spoken Latin at the ecumenical councils held during the reign of Theodosius II (d. 450 AD).[32]

Greek

Koine Greek had become the common language of the eastern Mediterranean and into Asia Minor after the conquests of Alexander the Great.[33] Lucian even imagines that Greek is the universal language of the dead in the underworld.[34] In late antiquity, a Greek-speaking majority lived in the Greek peninsula and islands, major cities of the East, and most of Anatolia.[35] Greek continued as the language of the Eastern Roman Empire, and developed into a distinctive medieval Greek that gave rise to modern Greek.[36]

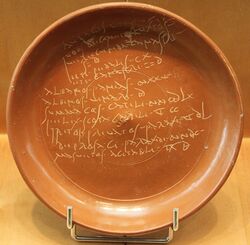

File:P.Ryl. I 61.tif The emperor Claudius tried to limit the use of Greek, and on occasion revoked the citizenship of those who lacked Latin. Even in addressing the Roman Senate, however, he drew on his own bilingualism in communicating with Greek-speaking ambassadors.[38] Suetonius quotes him as referring to "our two languages,"[39] and the employment of two imperial secretaries, one for Greek and one Latin, dates to his reign.[40]

The everyday interpenetration of the two languages is indicated by bilingual inscriptions, which sometimes even switch back and forth between Greek and Latin. The epitaph of a Greek-speaking soldier, for instance, might be written primarily in Greek, with his rank and unit in the Roman army expressed in Latin.[41]

In the Eastern empire, laws and official documents were regularly translated into Greek from Latin.[42] Both languages were in active use by government officials and the Church during the 5th century.[43] From the 6th century, Greek culture was studied in the West almost exclusively through Latin translation.[44] Latin loanwords appear liberally in Greek texts on technical topics from late antiquity and the Byzantine period.[45]

Language reform movements

Atticism was a trend of the Second Sophistic. Intellectuals such as Aelius Aristides sought to restore the standards of classical Greek characteristic of the Attic dialect, represented by Thucydides, Plato, Demosthenes, and other authors from the Classical period. Prose stylists who aspired to Atticism tried to avoid the vulgarisms of koine—an impractical goal, but this linguistic purism also reflected the 2nd-century flourishing of grammarians and lexicographers.[46] Expertise in language and literature contributed to preserving Hellenic culture in the Roman Imperial world.[47]

Among other reforms, the emperor Diocletian (reigned 284–305) sought to renew the authority of Latin, and the Greek expression ἡ κρατοῦσα διάλεκτος (hē kratousa dialektos) attests to the continuing status of Latin as "the language of power."[48] The scholar Libanius (4th century) regarded Latin as causing a decline in the quality of Greek rhetoric.[49] In the early 6th century, the emperor Justinian engaged in a quixotic effort to reassert the status of Latin as the language of law, even though in his time Latin no longer held any currency as a living language in the East.[50]

Regional languages

The dominance of Latin and Greek among the literate elite may obscure the continuity of spoken languages, since all cultures within the Roman Empire were predominantly oral.[51] In areas where Syriac, Coptic, and Aramaic were spoken, they coexisted with Greek.[52]

Aramaic and Syriac

Aramaic was the primary language of Syria and Mesopotamia, with several dialects.[53] Syriac was in use around Antioch, one of the three largest cities of the Empire, and particularly by Christians.[54] Syriac literature is known from the latter 2nd century, spreading from the Christian community in Edessa.[55] Early Syriac literature was produced in a largely Greek intellectual milieu until the 4th century, but was distinctive for its use of rich symbolism and emphasis on verse forms, and influenced Greek writers such as Eusebius, Basil and Theodoret.[56] Among the earliest Syriac literature was the Diatessaron of Tatian, and translations of sections from the Bible.[57]

The prolific Syrian scholar Bardesanes knew Greek and sent his son for schooling in Athens, but chose to write in his ethnic language. In addition to Syriac homilies and treatises, Bardesanes wrote 150 hymns "of enormous influence and doubtful doctrine".[58] Other Syriac literature of the time included Christian treatises, dialogues, and apocryphal Acts.[59] Some Syriac literature had Gnostic elements, and also played a role in the dissemination of Manicheanism. From the 5th century onward, it included Monophysite and Nestorian writings.[60]

Works by the Syriac writer Ephraim were translated into Greek.[61] The satirist and rhetorician Lucian came from Samosata in the province of Syria; although he wrote in Greek, he calls himself a Syrian, and a reference to himself as a "barbarian" suggests that he spoke Syriac.[62]

Soldiers from Palmyra even used their dialect of Aramaic for inscriptions, in a striking exception to the rule that Latin was the language of the military.[63]

Coptic

"Coptic" is the modern term for the form of ancient Egyptian that had developed in late antiquity.[64] Written Coptic as a literary language seems to have resulted from a conscious effort among Egypt's educated class to revive their cultural heritage.[65]

In the 4th century, Coptic script—based on the Greek alphabet with additional characters from Egyptian demotic to reflect Egyptian phonology—is found in documents in several dialects, including Old Bohairic, Fayumic, Achmimic, and Sahidic.[66] At this time Coptic emerged as a fully literary language, including major translations of Greek scriptures, liturgical texts, and patristic works.[67] From the 4th to 7th centuries, original works—including homilies, saints' lives, monastic rules, letters, and exhortations—were composed in Coptic, primarily in the Sahidic dialect.[68] As a writing system, Coptic was used for everyday purposes such as inventories and real estate transactions, as well as for poetry.[69] By the 640s, when Egypt came under Arab rule, Coptic-speaking Christians constituted the majority of the population.[70] At the end of the 7th century, legal texts might still be written in Coptic: in one example, a bilingual Greek-Arabic protocol with a reference to Mohammed precedes a document entirely in Coptic that invokes the Trinity.[71]

Punic

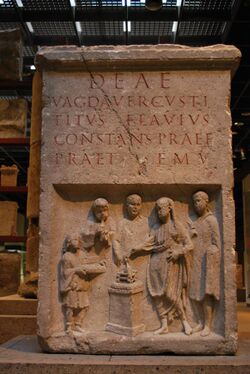

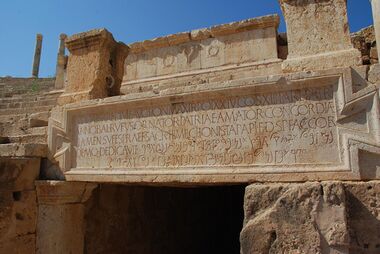

Punic, the Semitic language of the Carthaginians, continued to be used in North Africa during the Imperial period.[72] Before the Roman conquest in 146 BC, nearly all Punic inscriptions had been votive to the deities Tanit and Ba'al or funerary commemorations, but during the Roman era a broader range of content is found in Neo-Punic, often appearing with parallel texts in Latin or Greek.[73] A striking occurrence of Neo-Punic is found at the otherwise thoroughly Roman temple of Roma and Augustus, built 14–19 AD at Leptis Magna.[74] One of the latest Neo-Punic inscriptions on a monument dates to the reign of Domitian (81–96 AD).[75] No inscription in Punic script on stone can be dated later than the 2nd or 3rd century.[76] Latin script was used to write Punic in the 4th and 5th centuries.[77]

Punic was spoken at the highest level of society: the emperor Septimius Severus (reigned 193–211) was born in Leptis Magna and spoke Punic as well as Latin and Greek, while his sister supposedly had little command of Latin at all.[78] Augustine, who was from North Africa, several times mentions Punic; he observed that it was related to Hebrew and Syriac, and his knowledge of Punic helped him figure out transliterated Semitic words from the Bible.[79]

Celtic

Celtic languages at the beginning of the Imperial period include Gaulish, spoken in Gaul (Gallia, present-day France, Belgium, Switzerland and northwestern Italy); Celtiberian and Gallaecian, in parts of Hispania (Spain and Portugal); Brittonic in Britannia (Roman Britain), and Galatian, a branch of Celtic brought to Anatolia by the Gallic invasions of the 3rd century BC. The place name Galatia, a Roman province, derives from the Greek word for "Gauls" or "Celts", Galatai. Loanwords from Gaulish are recorded in Latin as early as the time of Ennius (ca. 239–169 BC), due to the presence of Celtic settlements on the Italian peninsula.[80] By late antiquity, some Gaulish words had become so Latinized that their origin was no longer recognized as such.[81]

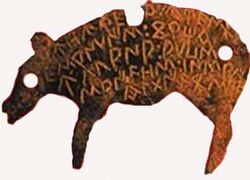

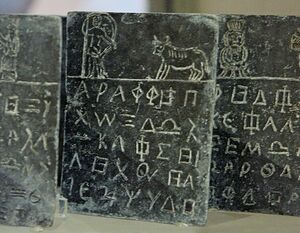

Celtiberian is documented as a written language only after contact with the Romans in the 2nd century BC.[82] Of 103 Celtiberian inscriptions, thirty in Iberian script are hospitality tokens (tesserae hospitales), twenty of which are in the shape of animals.[83] The social custom of pledging mutual support among families or communities was compatible with hospitium in Roman culture, and the Celtiberians continued to produce the tokens, though switching to Latin, into the 2nd century of the Imperial era.[84] Under Augustus, the territory of the Celtiberians became part of the Tarraconensis province.[85] Written Celtiberian ceases early in the reign of Augustus, if not before.[86]

Several references to Gaulish in late antiquity may indicate that it continued to be spoken. Irenaeus, bishop of Lugdunum (present-day Lyon) from 177 AD, complains that he has to communicate with his parishioners in their "barbarous tongue", probably Gaulish.[87] The jurist Ulpian (170–228) mentions the need to recognize Gaulish verbal contracts.[88] Lampridius says that a druidess made a prophecy in Gaulish to Alexander Severus (208–235).[89] Jerome (331–420), who had first-hand knowledge, observes that the Gallic Treveri speak a language "more or less the same" as that of the Galatians.[90] The collection of pharmacological recipes by Marcellus of Bordeaux (late 4th- or early 5th-century) contains several Gaulish words, mainly plant names, and seems to indicate that the language remained in use for at least some purposes such as traditional medicine and magic.[91] Sulpicius Severus (363–425), also from Gallia Aquitania, takes note of Gaulish-Latin bilingualism, with Gaulish as the first language. Other mentions of people who speak "in the Gallic manner" (gallice) or similar may refer to speaking Latin with a regional Gaulish accent.[92] Much of historical linguistics scholarship postulates that Gaulish was indeed still spoken as late as the mid to late 6th century in France.[93] Despite considerable Romanization of the local material culture, the Gaulish language is held to have survived and had coexisted with spoken Latin during the centuries of Roman rule of Gaul.[93]

Germanic

Next to nothing is recorded of the Germanic languages spoken in the Empire, with the exception of Gothic. A phrase of Gothic is quoted in an elegiac couplet from the Latin Anthology,[94] and more substantially parts of the Gospels were translated into Gothic and preserved by the 6th-century Codex Argenteus.[95] While Latin gained some Germanic loanwords, most linguistic influence ran the other way.[96]

Bilingualism in a Germanic language and Latin was especially important in the military for officers in command of units recruited from Germanic-speaking areas. Tacitus observes that Arminius, the Cheruscan officer who later led a disastrously successful rebellion against the Romans, was bilingual.[97] The emperor Julian employed a bilingual Germanic military tribune as a spy.[98] The officers and secretaries who kept the records preserved in the Vindolanda tablets were Batavian, but their Latin contains no hint; the common soldiers of their units, however, may have retained their Germanic speech.[99] Less commonly, Latin-speaking officers learned a Germanic language through their service and acted as interpreters.[100] Acquiring Germanic might be regarded as a dubious achievement inducing anxieties of "barbarism": in 5th-century Gaul, Sidonius Apollinaris thinks it funny that his learned friend Syagrius has become fluent in Germanic.[101]

Multilingualism

Trilingualism was perhaps not uncommon among educated people who came from regions where a language other than Latin or Greek was spoken. The Latin novelist Apuleius also wrote in Greek, and had learned Punic from his mother.[102] The Babatha Archive is a suggestive example of practical multilingualism. These papyri, named for a Jewish woman in the province of Arabia and dating from 93 to 132 AD, mostly employ Aramaic, the local language, written in Greek characters with Semitic and Latin influences; a petition to the Roman governor, however, was written in Greek.[103]

One striking example of multilingualism as well as multiculturalism in the Empire is a 2nd-century epitaph for a woman named Regina, discovered in 1878 near the Roman fort at South Shields, northeast England. The inscription is written in Latin and Palmyrene Aramaic, the language of Regina's husband, Barates, who has been identified with a standardbearer (vexillarius) of that name from Palmyra, Syria.[104] He was most likely in the military stationed along Hadrian's Wall. The Latin, however, is constructed grammatically in the manner of Greek honorific inscriptions typical of Palmyra, suggesting that Barates was bilingual in Aramaic and Greek, and added Latin as a third language. The Latin portion is larger and longer, and provides most of the information. The Palmyrene is carved in a fluid cursive script, and conveys only the name of Regina and an expression of grief. Since few people in Britain could have read Palmyrene, its use may be Barates' personal statement of his identity and emotions. A fourth linguistic element is the name Regina, which can be either Latin or Celtic. Such names seem often to have been chosen for their deliberate duality. Regina herself is identified as from the British Catuvellauni, a people whose civitas capital was Verulamium, but the Gallo-Brittonic spelling Catuallauna (feminine) is used in the Latin inscription.[105]

Geographical distribution

Italian peninsula and Sicily

In Italy, the written use of Latin had replaced Oscan—like Latin, an Italic language—and Etruscan by the end of the 1st century AD.[106] Oscan graffiti are preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79 at Pompeii and Herculaneum, which was in the Oscan region, and a couple may date before or after an earlier regional earthquake in AD 62.[107] In the mid-1st century, the emperor Claudius, who had keen antiquarian interests, knew Etruscan and wrote a multi-volume history of the Etruscans, but the work has not survived.[108]

Multilingualism had been characteristic of Sicily for centuries, resulting from occupations by the Carthaginians, Greeks, and Romans. While the slave trade during the Republican period brought speakers of Greek and other languages from the East to the island, Greek was the language of higher-status persons such as government officials and businessmen during the Imperial era.[109] Immigration to Sicily in the early Empire originated more often in places where Latin was spoken than in Greek-speaking areas. African speakers of Latin were a significant presence in Sicily.[110] Christian inscriptions are far more likely to be in Greek.[111] In late antiquity, Greek-Latin bilingualism was common enough that it would have been acquired through everyday personal interaction.[112] The Jewish communities of Syracuse seem to have been bilingual in Greek and Hebrew.[113] There is some Sicilian evidence of Syriac.[114]

Western provinces

In the Western Empire, Latin gradually replaced the Celtic languages, which were related to it by a shared Indo-European origin. Commonalities in syntax and vocabulary facilitated the adoption of Latin.[115] Mediterranean Gaul (southern France) had become trilingual (Greek, Latin, Gaulish) by the mid-1st century BC.[116] The importance of Latin in gaining access to the ruling power structure caused the rapid extinction of inscriptions in scripts that had been used to represent local languages on the Iberian peninsula (Hispania) and in Gaul. Among other aspects of a distinctive Gallo-Roman culture was the creation of Gallo-Latin text.[117] In Latin commemorative inscriptions, individuals with Celtic names rarely identify themselves as "Celtic" or "Gallic"; they are much more likely to name the people of their civitas (such as Aedui, Remi, Pictones)[118] or their voting tribe (tribus) as Roman citizens. Several major writers of Latin came from the Iberian peninsula in the Imperial period, including Seneca, Lucan, Quintilian,[119] Martial, and Prudentius. However despite acquisition of Latin, Gaulish is held by some to have held on quite a long time, lasting at least until the middle of the 6th century CE, despite considerable Romanization in the local material culture.[93]

Most of the 136 Greek inscriptions from Mediterranean Gaul (the Narbonensis), including those from originally Greek colonies, are post-Augustan.[120] Their content indicates that Greek was used increasingly for specialized purposes: "education, medicine, acting, agonistic activities, art, magic, religion, including Christianity".[121] Inscriptions from Marseilles (ancient Massilia), founded as a Greek Phocaean colony around 600 BC, show the continued use of Greek, especially in education and medicine, into the 2nd and 3rd centuries of the Imperial era.[122] In the 4th century, the Latin poet and scholar Ausonius, from Gallia Aquitania (present-day Bordeaux), characterizes his physician father as speaking Attic Greek with more eloquence than Latin.[123]

Basque, not an Indo-European language, survived in the region of the Pyrenees.[124] The people of southwestern Gaul and northeastern Hispania (roughly present-day Aquitaine and Navarre) were regarded by Julius Caesar as ethnically distinct from the Celts, and the Aquitanian language they spoke was Vasconic like Basque, judging from place names. The Aquitani adopted Latin under Roman rule.[125]

Gaulish survived in Gaul into the late 6th century, and played a decisive role in the formation of Gallo-Romance languages.[93] Latin did not become as deeply entrenched in the province of Britannia, and may have dwindled rapidly after the Roman withdrawal around 410 AD, although pockets of Latin-speaking Britons survived in western Britain until about 700 AD.[126][127] The evidence of Latin loanwords into Brittonic suggests that the Latin of Roman Britain was academic, in contrast to the everyday conversational Latin ("Vulgar" Latin) on the continent.[128]

African provinces

In the provinces of Africa westwards of Cyrenaica (a region colonised by Greeks since the 7th century BC), the people of Carthage and other Phoenician colonies spoke and wrote Punic, with Latin common in urban centers. Other Roman Africans spoke Afroasiatic languages (Libyan, Numidian), debatably early versions of Berber.[129]

Punic was used for legends on coins during the time of Tiberius (1st century AD), and Punic inscriptions appear on public buildings into the 2nd century, some bilingual with Latin.[130] Inscriptions might also be trilingual: one pertaining to Imperial cult presents "the official Latin, the local Punic, and the Greek of passing traders and an educated or cosmopolitan elite".[131]

Inscriptions in Libyan use a script similar to tifinagh, usually written vertically from the bottom up. The 23 characters are "of a rather rigid geometric form".[132] Bilingual examples are found with either Punic or Latin, and indicate that some people who could write these languages could also at least transliterate their names into the Libyan script. Although Libyan inscriptions are concentrated southeast of Hippo, near the present-day Algerian-Tunisia border, their distribution overall suggests that knowledge of the language was not confined to isolated communities.[133]

Notable writers of Latin from Africa during the Imperial period include the novelist Apuleius, and the Church Fathers Tertullian and Augustine. Latin-speaking communities remained in North Africa, particularly around Carthage, during the period of the Vandal Kingdom (435–534), but died out by the late 7th century, with the Arab conquest.[134]

Roger Blench (2018)[135] suggests that although Berber had split off from Afroasiatic several thousand years ago, Proto-Berber itself can only be reconstructed to a period as late as 200 CE, with modern-day Berber languages displaying low internal diversity. The presence of Punic borrowings in Proto-Berber points to the diversification of modern Berber language varieties subsequent to the fall of Carthage in 146 B.C.; only Guanche and Zenaga lack Punic loanwords.[135] Additionally, Latin loanwords in Proto-Berber point to the breakup of Proto-Berber between 0-200 A.D. During the time of the Roman Empire, Roman innovations such as the ox-plough, camel, and orchard management were adopted by Berber communities along the limes, or borders of the Roman Empire, resulting in a new trading culture involving the use of a lingua franca which became Proto-Berber.[135]

Egypt

In Egypt, Coptic predominated,[136] but Greek had been in use since the conquest of Alexander, and Latin and Greek were the administrative languages during the Roman Imperial period.[137] Alexandria, founded in 331 BC under Greek rule and one of the three largest cities of the Roman Empire, was a leading city in Greek intellectual life during the Hellenistic and Imperial periods. Famed for the Library of Alexandria, it was also a center for the dissemination of Christianity, which spread first among Greek speakers in Egypt.[138]

Around 700 AD, Greek was replaced for administrative use by Arabic after the Arab conquest of Egypt. Coptic began to decline, and from this point, was preserved mainly for liturgical purposes.[139]

Eastern empire

Although Greek was in common use around the Mediterranean and into Asia Minor even beyond Imperial borders, linguistic distribution in the eastern part of the Empire was complex. Now-extinct languages in Anatolia included Galatian (the form of Celtic introduced by invading Gauls in the 3rd century BC), Phrygian, Pisidian, and Cappadocian, attested by Imperial-era inscriptions.[140] Christian sources also mention the survival of Galatian, Cappadocian, Mysian, and Isaurian in Asia Minor.[141] Like Greek and Latin, these are sometimes categorized as Indo-European. Phrygian is not named as a language in a literary text until the 6th century, but is preserved in about a hundred funerary inscriptions in Greek script, most accompanied by Greek text as well and dating from the 3rd century.[142] A Cappadocian accent in speaking Greek seems to be mentioned in a few sources.[143]

Outside the military, Latin never became the language of everyday life in the East. An exception was the Roman colony of Berytus (present-day Beirut), where a Latin education could be obtained, and which became famous for its school of Roman law.[144]

Danubian provinces and Balkans

The Danubian provinces lay within a geographical area encompassing the middle and lower Danube basins, the Eastern Alps, the Dinarides, and the Balkans. Provinces in this general region include Noricum, Dacia, Dalmatia, Moesia, Thrace, Scythia, and Pannonia.[145] The relative influence of Latin versus Greek and vice versa in this area and in the Balkans in general, is sometimes demarcated by the Jireček Line.

Greek had been in use in the southern part of the Balkans since the late 4th century BC, as a result of the Macedonian conquests of Philip and Alexander. The ancient Macedonian language, perhaps a Greek dialect,[146] may have been spoken in some parts of what is now Macedonia and northern Greece; to the north of this area, Paeonian would have been used, and to the south Epirot, both scantily attested.[147]

Illyrian was spoken in the northwest, and to the northeast Thracian and Dacian.[148] These three languages, all Indo-European, are thought to be candidates for the ancestor of Albanian.[149] From his exile in Tomis on the Black Sea (present-day Constanța, Romania), the Augustan poet Ovid learned Getic (Dacian) and Sarmatian, and noted that Greek was spoken with a markedly Getic accent.[150] Inscriptions from Tomis in the Imperial period are generally Greek, with Thracian personal names and religious references.[151]

Jewish diaspora

Inscriptions in Greek and Latin set up by Jews attest to Jewish bi- or multilingualism, and their distribution in the Empire reflects the Jewish diaspora.[152] These may have the Hebrew tag shalom at the end.[153] Evidence for Jews in Egypt is preserved by papyri until the Jewish revolt of 116–117.[154] In the first half of the 5th century, Greek coexisted with Hebrew and Jewish Aramaic in the Jewish communities of Palaestina Prima and Secunda, and is found in mosaic inscriptions even in synagogues.[155]

Like the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible that predated the Imperial era, Jewish literature in Greek under the Empire was written mainly for Jews who spoke Greek.[156] Some Jews writing in Greek during the late Hellenistic and early Imperial period—notably the philosopher Philo and the historian Josephus—included gentiles among their intended audience.[157] The Sibylline Oracles and the Wisdom of Solomon are other examples of Jewish literature in Greek from this general period.[158]

No surviving Greek texts written after the year 100 CE can be securely identified as having a Jewish author. After this time, Jewish writings in Greek became irrelevant to Christians, who were thus unlikely to preserve them. The manuscription tradition of medieval Jewish culture has preserved only writings in Hebrew and Aramaic.[159]

Christian communities

The Epistle to Diognetus states that language was not a determining factor in Christian identity; Christians might speak any language.[160] By late antiquity, at least some Christian literature had been created for virtually every language in regular use throughout the Empire.[161]

The international use of Greek was one factor enabling the spread of Christianity, as indicated for example by the use of Greek for the Epistles of Paul.[163] Constantine, the first emperor to actively support Christianity, presumably knew some Greek, but Latin was spoken in his court, and he used an interpreter to address Greek-speaking bishops at the Council of Nicaea.[164] In the Christian Latin West, Greek became associated with "paganism" and regarded as a foreign language (lingua peregrina).[165] Saint Augustine confessed that he loathed Greek and found it hard to learn.[166] By late antiquity, however, it was possible to speak Greek as a primary language while not conceiving of oneself as a "Hellene" in matters of religion and culture.[167] In the first half of the 5th century, Greek was the standard language in which bishops communicated,[168] and the Acta Conciliorum ("Acts of the Church Councils") were recorded originally in Greek and then translated into Latin, Syriac, or Coptic.[169] During this period, Latin played only a subordinate role in the ecumenical councils, as did representatives from the Western empire.[170] Although traditionally Armenian is regarded as having been established as a Christian language by this time, it does not appear in the Acta.[171] There are hints that Coptic might be spoken at the councils, but no secure record.[172] On-the-spot translation into Greek was available for the participant who used his own language, including some who are referred to as "Arabs", "Saracens" or "Ishmaelites".[173] Christian content has been found in a few Arabic inscriptions from the 6th century.[174]

Ritual language

The form of private or personalized ritual characterized as "magic"[175] might be conducted in a hodgepodge of languages. Magic, and even some therapies for illnesses, almost always involved incantation or the reciting of spells (carmina), often accompanied by the ritualized creation of inscribed tablets (lamellae) or amulets. These are known from both archaeological artifacts and written texts such as the Greek Magical Papyri, a collection of spells dating variously from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD. Although Augustus attempted to suppress magic by burning some 2,000 esoteric books early in his reign,[176] magical practices were disseminated widely throughout the Greco-Roman world, and attest to an awareness of multilingualism among the peoples of the Empire.[177] Spells were not translated, because their efficacy was thought to reside in their precise wording;[178] a language such as Gaulish thus may have persisted for private ritual purposes when it no longer had everyday currency.[179]

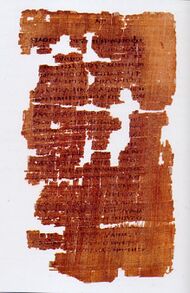

The Greek Magical Papyri (PGM) reflect Greco-Egyptian syncretism, incorporating not only Egyptian and Hellenistic religion, but Near Eastern elements, including Jewish magic and dashes of Christian magic. Egyptian and Greek deities, the God of the Jews and Judaic angels, and Jesus are named. The PGM are written primarily in Greek with substantial passages in Demotic Egyptian[180] and inserted strings of syllables that are "pronounceable, though unintelligible".[181] These voces magicae ("magic words") occur throughout magic texts and inscriptions,[182] and often suggest corrupt Coptic or Egyptian,[183] Hebrew,[184] Aramaic or other Semitic languages,[185] and Celtic.[186] Hebrew and Greek appear in Demotic magical texts; Coptic magic incorporates Hebrew; Egyptian pops up in Latin spells.[187] While many voces magicae may be deliberate neologisms or obscurantism,[188] scholars have theorized that the more recognizable passages may be the products of garbled or misunderstood transmission, either in copying a source text or transcribing oral material.[189]

Inscriptions for the practice of magic in Gaul show the characteristic use of Greek for spells in the Imperial period. A 2nd-century curse tablet from Autun (Augustodunum) lists the names of those to be cursed in Latin, two magic words in Greek, and a series of voces magicae.[190] A defixio (binding spell) from Amélie-les-Bains seems composed in Celtic with bits of Latin.[191] A lamella from Roman Britain has been interpreted as Hebrew written in Greek characters.[192]

Christians in late antiquity might insert Hebrew into Greek exorcisms.[193] Saint Jerome reports an odd story about a Frankish-Latin bilingual man of the Candidati Imperial bodyguard who, in a state of demonic possession, began speaking perfect Aramaic, a language he did not know.[194]

Legal language

Roman law was written in Latin, and the "letter of the law" was tied strictly to the words in which it was expressed.[195] Any language, however, could be binding in more general verbal contracts and procedures grounded in the ius gentium or international law.[196] The ius gentium was not a written legal code, but was thought to exist among all peoples as a matter of natural law. Roman jurists show a concern for local languages such as Punic, Gaulish, and Aramaic in assuring the correct understanding and application of laws and oaths.[197]

While the birth certificates and wills of Roman citizens had to be written in Latin until the 220s,[198] in the legal opinion of Ulpian (ca. 215), fideicommissa (bequests in trust[199]) were not limited to Latin or even Greek, but could also be created in "Punic, Gaulish or any other" language.[200] Originally, a testator's fideicommissum placed the heir under a moral rather than legal obligation,[201] and Ulpian asserted that "any kind of speech contains the obligation of its words, provided that each party understands the other's language himself or through accurate interpreters".[202] The jurist Gaius distinguished between verbal contracts that derived their validity from formulaic utterance in Latin, and obligations expressing a mutual understanding of the ius gentium regardless of whether the parties were Roman or not.[203]

Linguistic legacy

After the decentralization of political power in late antiquity, Latin developed locally into branches that became the Romance languages, including Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Romanian, Catalan, Sardinian, Aromanian, African Romance, Mozarabic, Dalmatian, and Venetian, among others. As an international language of learning and literature, Latin itself continued as an active medium of expression for diplomacy and for intellectual developments identified with Renaissance humanism up to the 17th century, and for law and the Roman Catholic Church to the present.[204]

Greek continued as the language of the Byzantine Empire, but never replaced certain languages with which it had long coexisted, such as Coptic in Egypt, and Aramaic in Syria and Mesopotamia.[205]

References

- ↑ Richard Brilliant, "Scenic Representations," in Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979), pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Bruno Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," translated by James Clackson, in A Companion to the Latin Language (Blackwell, 2011), p. 560.

- ↑ Alex Mullen, "Introduction: Multiple Languages, Multiple Identities," in Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds (Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 28.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 554, 556.

- ↑ J.N. Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," Classical Quarterly 53.1 (2003), pp. 185–186, 205.

- ↑ Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State, p. 5.

- ↑ The Oxford Handbook of the Literatures of the Roman Empire, edited by Daniel L. Selden and Phiroze Vasunia (Oxford University Press). Richard Valantasis, introduction to Religions of Late Antiquity in Practice (Princeton University Press, 2000), p. 11.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages in the Roman Empire," pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Joseph Eska, "Inscriptions in the Celtic World," in Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-Clio, 2006), pp. 965–970.

- ↑ Tore Janson, A Natural History of Latin (Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 87.

- ↑ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, pp. 264–265.

- ↑ James Clackson, introduction to A Companion to the Latin Language, p. 1.

- ↑ Virgil, Aeneid 12.834 and 837; Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 549, 563; Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," p. 184.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 552.

- ↑ József Herman, Vulgar Latin, translated by Roger Wright (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000, originally published 1975 in French), p. 10.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 549; Charles Freeman, The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World (New York: Penguin, 1999), pp. 389–433.

- ↑ Augustine of Hippo, De Civitate Dei 19.7.18, as cited by Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 549.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 549, citing Plutarch, Life of Alexander 47.6.

- ↑ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, p. 265.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 92.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 92.

- ↑ Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (University of California Press, 2000), pp. 86–87.

- ↑ William V. Harris, Ancient Literacy (Harvard University Press, 1989), p. 5; William A. Johnson, Ancient Literacies: The Culture of Reading in Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2009), pp. 3–4, especially note 5; T.J. Kraus, "(Il)literacy in Non-Literary Papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt: Further Aspects of the Educational Ideal in Ancient Literary Sources and Modern Times," Mnemosyme 53.3 (2000), p. 325; Marietta Horster, "Primary Education," in The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World, pp. 89, 97–98.

- ↑ Christian Laes, Children in the Roman Empire: Outsiders Within (Cambridge University Press, 2011, originally published in Dutch 2006), p. 108; Horster, "Primary Education," in The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World, p. 89.

- ↑ IG 14.1125

- ↑ Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire, p. 101; Kraus, "(Il)literacy in Non-Literary Papyri from Graeco-Roman Egypt," pp. 325–327.

- ↑ Susan P. Mattern, Rome and the Enemy: Imperial Strategy in the Principate (University of California Press, 1999), p. 197; Teresa Morgan, Literate Education in the Hellenistic and Roman Worlds (Cambridge University Press, 1998, 2000), pp. 1–2 et passim; Greg Woolf, "Literacy or Literacies in Rome?" in Ancient Literacies, p. 46ff.; Horster, "Primary Education," in The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World, p. 97. Ando poses the question as "what good would 'posted edicts' do in a world of low literacy?' in Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire, p. 101.

- ↑ Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire, pp. 152, 210.

- ↑ Edith Hall, introduction to New Directions in Ancient Pantomime (Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Rance, "The De Militari Scientia or Müller Fragment," pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 100.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 279; Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, p. 5.

- ↑ Lucian, Dialogue of the Dead 25; Anderson, The Second Sophistic, p. 194.

- ↑ Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, p. 5.

- ↑ Stefan Zimmer, "Indo-European," in Celtic Culture: An Historical Encyclopedia, p. 961.

- ↑ Cicero, In Catilinam 2.15, P.Ryl. I 61 "recto".

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 552.

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Claudius 42.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 553; Lee I. Levine, Jerusalem: Portrait of the City in the Second Temple Period (538 B.C.E. – 70 C.E.) (Jewish Publication Society, 2002), p. 154.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 556; Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," p. 200.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 553–554.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, pp. 93¬94.

- ↑ Moatii, "Translation, Migration, and Communication," p. 112.

- ↑ Rance, "The De Militari Scientia or Müller Fragment," p. 63.

- ↑ Anderson, The Second Sophistic, pp. 87–91.

- ↑ Anderson, The Second Sophistic, p. 101.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 560.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 560; A.H.M. Jones, The Decline of the Ancient World (Longmanns, 1966), p. 346.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 562–563.

- ↑ Richard Miles, "Communicating Culture, Identity, and Power," in Experiencing Rome: Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire (Routledge, 2000), pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 95.

- ↑ Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, p. 5.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 4.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 5.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 6.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 5.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," pp. 4–5.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 5.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," pp. 5–6.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 7.

- ↑ Edwards et al., introduction to Apologetics in the Roman Empire, p. 7; Matthew W. Dickie, "Lucian's Gods: Lucian's Understanding of the Divine," in The Gods of Ancient Greece: Identifies and Transformations (Edinburgh University Press, 2010), p. 350.

- ↑ Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," p. 199.

- ↑ Mark Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone and Beyond: Studies in Early Monastic Literature and Scriptural Interpretation (Studia Anselmiana, 2012), p. 225.

- ↑ Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone, p. 226.

- ↑ Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone, p. 226.

- ↑ Maged S.A. Mikhail, "An Historical Definition for the 'Coptic Period'," in Coptic Studies on the Threshold of a New Millennium. Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Coptic Studies Leiden 2000 (Peeters, 2004), vol. 2, p. 972.

- ↑ Mikhail, "An Historical Definition for the 'Coptic Period'," p. 973; Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone, p. 226.

- ↑ Mikhail, "An Historical Definition for the 'Coptic Period'," p. 973.

- ↑ Mikhail, "An Historical Definition for the 'Coptic Period'," p. 974.

- ↑ Mikhail, "An Historical Definition for the 'Coptic Period'," p. 974.

- ↑ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, pp. 201, 213.

- ↑ Andrew Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa: Function and Display," in Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds, pp. 266–268.

- ↑ Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," p. 282.

- ↑ Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," p. 295.

- ↑ Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," p. 269.

- ↑ Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," p. 307ff.

- ↑ Karel Jongeling and Robert M. Kerr, Late Punic Epigraphy (Mohr Siebeck, 2005), p. 4; Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," p. 305.

- ↑ Jongeling and Kerr, Late Punic Epigraphy, p. 4.

- ↑ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 185 et passim.

- ↑ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 195.

- ↑ Fiona A. Rose, "Text and Image in Celtiberia: The Adoption and Adaptation of Written Language into Indigenous Visual Vocabulary," Oxford Journal of Archaeology 22.2 (2003), p. 155.

- ↑ Rose, "Text and Image in Celtiberia," pp. 157, 159.

- ↑ Rose, "Text and Image in Celtiberia," p. 159; Leonard A. Curchin, The Romanization of Central Spain: Complexity, Diversity and Change in a Provincial Hinterland (Routledge, 2004), p. 120.

- ↑ Rose, "Text and Image in Celtiberia," p. 156.

- ↑ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 280.

- ↑ Irenaeus, Against Heresies I, preface; Pierre-Yves Lambert, La langue gauloise: description linguistique, commentaire d'inscriptions choisies (Editions Errance, 2003), p. 10.

- ↑ Digest 31.1.11; Lambert, La langue gauloise, p. 10.

- ↑ Lambert, La langue gauloise, p. 10.

- ↑ Jerome, commentary on the Letter to the Galatians; Lambert, La langue gauloise, p. 10.

- ↑ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 192.

- ↑ Lambert, La langue gauloise, p. 10.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 93.2 93.3 Laurence Hélix (2011). Histoire de la langue française. Ellipses Edition Marketing S.A.. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-7298-6470-5. "Le déclin du Gaulois et sa disparition ne s'expliquent pas seulement par des pratiques culturelles spécifiques: Lorsque les Romains conduits par César envahirent la Gaule, au 1er siecle avant J.-C., celle-ci romanisa de manière progressive et profonde. Pendant près de 500 ans, la fameuse période gallo-romaine, le gaulois et le latin parlé coexistèrent; au VIe siècle encore; le temoignage de Grégoire de Tours atteste la survivance de la langue gauloise."

- ↑ Latin Anthology 285 (= 279 in the edition of Shackleton Bailey): Inter 'eils' Goticum 'scapia matzia ia drincan' / non audet quisquam dignos edicere versus ;Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 275.

- ↑ Tore Janson, A Natural History of Latin (Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 87.

- ↑ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 274.

- ↑ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, pp. 274–275, citing Tacitus, Annales 2.10.3.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus 18.2.2; Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 275.

- ↑ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 276.

- ↑ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, pp. 276–277.

- ↑ Sidonius, Epistle 5.5; Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 277.

- ↑ Moatti, "Translation, Migration, and Communication," p. 111, note 9.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 553–555.

- ↑ The second inscription comes from Corstopitum (Corbridge), about 50 kilometers away.

- ↑ Mullen, introduction to Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Miles, "Communicating Culture, Identity, and Power," p. 58.

- ↑ James Clackson and Geoffrey Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), p. 83; Herman, Vulgar Latin, p. 11.

- ↑ Giuliano Bonfante and Larissa Bonfante, The Etruscan Language (Manchester University Press, rev. ed. 2002), p. 33.

- ↑ Kalle Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," in Language and Linguistic Contact in Ancient Sicily (Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 332.

- ↑ Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," pp. 336–338.

- ↑ Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," 339–340.

- ↑ Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," p. 363.

- ↑ Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," p. 366.

- ↑ Korhonen, "Sicily in the Roman Imperial Period," p. 366.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," p. 550; Stefan Zimmer, "Indo-European," in Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-Clio, 2006), p. 961; Leonard A. Curchin, "Literacy in the Roman Provinces: Qualitative and Quantitative Data from Central Spain," American Journal of Philology 116.3 (1995), p. 464.

- ↑ Varro as quoted by Isidore of Seville, Origines 15.1.63, trilingues quod et graece loquantur et latine et gallice; Edgar C. Polomé, "The Linguistic Situation in the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II (De Gruyter, 1983), p. 527; Philip Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001), p. 15.

- ↑ Miles, "Communicating Culture, Identity, and Power," pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, p. 8, especially note 10.

- ↑ Herman, Vulgar Latin, p. 12.

- ↑ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, pp. 266, 273.

- ↑ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, p. 266.

- ↑ Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, p. 267.

- ↑ Ausonius, Epicedion in patrem 9–10 (a first-person poem written in the voice of his father); J.N. Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language (Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 356–357, especially note 109, citing R.P.H. Green, The Works of Ausonius (Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 1991), p. 276 on the view that Gaulish was the native language of Iulius Ausonius. Adams is inclined to believe that he simply spoke Latin with a Gaulish accent. See also Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, p. 269 (note 19).

- ↑ Karmele Rotaetxe, "Basque as a Literary Language," in A Comparative History of Literatures in the Iberian Peninsula (John Benjamins, 2010), p. 446.

- ↑ Clackson and Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2012). Wales and the Britons, 350-1064. p. 75. ISBN 978-0198217312.

- ↑ Herman, Vulgar Latin, p. 12.

- ↑ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 127.

- ↑ Clackson and Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language, pp. 86–87; Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," pp. 128–129, expressing skepticism about identifying the non-Punic languages of North Africa as "Berber".

- ↑ Miles, "Communicating Culture, Identity, and Power," pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Wilson, "Neo-Punic and Latin Inscriptions in Roman North Africa," pp. 284, 286.

- ↑ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 129.

- ↑ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," pp. 128–130.

- ↑ Herman, Vulgar Latin, p. 12.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 135.2 Blench, Roger. 2018. Reconciling archaeological and linguistic evidence for Berber prehistory.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 558–559.

- ↑ Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone, p. 226.

- ↑ Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone, p. 225.

- ↑ Sheridan, From the Nile to the Rhone, p. 226.

- ↑ Miles, "Communicating Culture, Identity, and Power," p. 58; Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, pp. 5–7.

- ↑ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 126.

- ↑ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 126.

- ↑ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 127, citing Philostratus and Gregory of Nyssa.

- ↑ Teresa Morgan, "Education," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 18.

- ↑ J.J. Wilkes, "The Roman Danube: An Archaeological Survey," Journal of Roman Studies 95 (2005), p. 124

- ↑ Not to be confused with the modern Macedonian language, which is Slavonic.

- ↑ Clackson and Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language, p. 86.

- ↑ Clackson and Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language, p. 86.

- ↑ Clackson and Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language, p. 86.

- ↑ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 126, citing also L.P. Wilkinson, Ovid Recalled (1955), ch. 10.

- ↑ Millar, "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire," p. 126.

- ↑ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, pp. 48, 130.

- ↑ Mullen, introduction to Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds, p. 18.

- ↑ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, p. 48.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 95.

- ↑ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, p. 79.

- ↑ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, pp. 53, 78.

- ↑ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Goodman, Mission and Conversion, p. 48.

- ↑ Simon Price, "Latin Christian Apologetics: Minucius Felix, Tertullian, and Cyprian," in Apologetics in the Roman Empire: Pagans, Jews, and Christians (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 103.

- ↑ Valantasis, introduction to Religions of Late Antiquity, p. 11.

- ↑ Robin Margaret Jensen, Understanding Christian Art (Routledge, 2000), p. 51; Alison E. Cooley, The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy (Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 233.

- ↑ Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State, p. 5.

- ↑ Mark Edwards, "The Constantinian Circle and the Oration to the Saints," in Apologetics, p. 255.

- ↑ Augustine, Confessions 1.14.23; Moatii, "Translation, Migration, and Communication," p. 112.

- ↑ Augustine, Confessions 1.13.20 and 2.38.91; Moatti, "Translation, Migration, and Communication," p. 112, note 16.

- ↑ Simon Swain, "Defending Hellenism: Philostratus, in Honour of Apollonius," in Apologetics, p. 173.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 98.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 104.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 105.

- ↑ Millar, A Greek Roman Empire, p. 105.

- ↑ Alderik Bloom, "Linguae sacrae in Ancient and Medieval Sources: An Anthropological Approach to Ritual Language," in Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds, p. 124, prefers "ritual" to the problematic distinction between "religion" and "magic" in antiquity.

- ↑ Hans Dieter Betz, "Introduction to the Greek Magical Papyri," The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells (University of Chicago Press, 1986, 1996), p. xli.

- ↑ William M. Breshear, "The Greek Magical Papyri: An Introduction and Survey," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II 18.5 (1994), passim.

- ↑ Blom, "Linguae sacrae," p. 130.

- ↑ James Clackson, "Language Maintenance and Shift," in Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds, p. 55.

- ↑ Betz, introduction to "The Greek Magical Papyri," pp. xlv–xlvi; Janet H. Johnson, "Introduction to the Demotic Magical Papyri," p. lv in the same volume (page numbering of the two introductions is independent, not sequential).

- ↑ Campbell Bonner, “Harpokrates (Zeus Kasios) of Pelusium,” Hesperia 15 (1946), p. 54.

- ↑ In addition to the PGM, charms are common in texts from late antiquity, including the collected pharmacological recipes of Marcellus of Bordeaux; Pseudo-Apuleius, Herbarius; Sextus Placitus, Liber medicinae ex animalibus; Hippiatrica; Physica Plinii; Pseudo-Dioscurides, De herbis feminis; and the Anglo-Saxon Lacnunga. See Blom, "Linguae sacrae," p. 127, note 22. Inscriptions are found on amulets, intaglio gems, incantation bowls, curse tablets, and lamellae (metal-leaf tablets).

- ↑ Fritz Graf, “Prayer in Magic and Religious Ritual,” in Magika Hiera: Ancient Greek Magic and Religion, (Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 191, and Roy Kotansky, “Incantations and Prayers for Salvation on Inscribed Greek Amulets,” also in Magika Hiera, p. 132, note 60, both on Egyptian; John G. Gager, “A New Translation of Ancient Greek and Demotic Papyri, Sometimes Called Magical,” Journal of Religion 67 (1987), p. 83 on Coptic.

- ↑ Gager, “A New Translation of Ancient Greek and Demotic Papyri,", p. 83; Paul Mirecki, “The Coptic Wizard's Hoard,” Harvard Theological Review 87 (1994), pp. 457–458.

- ↑ Kotansky, “Incantations and Prayers for Salvation," p. 117.

- ↑ Lambert, La langue gauloise, pp. 176–178, particularly on a 3rd–4th century tablet from the Gallo-Roman town Rom that may be Celtic in a Latin context.

- ↑ Breshear, "The Greek Magical Papyri," p. 3435.

- ↑ Matthias Klinghardt, “Prayer Formularies for Public Recitation: Their Use and Function in Ancient Religion,” Numen 46 (1999), p. 50; Hans Dieter Betz, "Secrecy in the Greek Magical Papyri," in Secrecy and Concealment: Studies in the History of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Religions (Leiden 1995), 153–175, especially 158–164; Brashear, “The Greek Magical Papyri," p. 3434.

- ↑ Richard Janko, “Forgetfulness in the Golden Tablets of Memory,” Classical Quarterly 34 (1984), pp. 89–100 on problems of oral transcription; Graf, “Prayer in Magic and Religious Ritual,” p. 191; Betz, "The Greek Magical Papyri," p. xlvi; Breshear, "The Greek Magical Papyri," pp. 3434–3438.

- ↑ IGF 159; Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean, pp. 266–267.

- ↑ Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 194.

- ↑ L.C. Youtie, "A Medical Prescription for Eye-salve," ZPE 23 (1976), pp. 121–29; Collingwood and Wright, “Roman Inscriptions of Britain I” (Oxford 1965), p. 144, no. 436.

- ↑ According to Origen, Commentary on Matthew (PG 13.1757): Hebraeo acceptis adiurant daemonia; Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 194.

- ↑ Jerome, Vita Hilarionis 13.7: videres de ore barbaro, et qui Francam tantum et Latinam linguam noverat, Syra ad purum verba resonare: Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, p. 275.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 3.

- ↑ MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," pp. 558–559.

- ↑ Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," pp. 186–187.

- ↑ W.W. Buckland A Textbook of Roman Law from Augustus to Justinian, 3rd ed. edited by Peter Stein (Cambridge University Press, 1921, 2007), p. 9.

- ↑ Digest 32.11 pr.; Ramsey MacMullen, "Provincial Languages in the Roman Empire," American Journal of Philology 87.1 (1966), p. 2.

- ↑ Adolf Berg, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (American Philosophical Society, 1980, 1991), pp. 470–471. In late antiquity, fideicommissa could be legally binding as well.

- ↑ Digest 45.1.1.6; MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," p. 2.

- ↑ Gaius, Institutiones 3.93; MacMullen, "Provincial Languages," pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Françoise Waquet, Latin, Or, The Empire of the Sign: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century (Verso, 2001; originally published 1998 in French), pp. 1–2; Kristian Jensen, "The Humanist Reform of Latin and Latin Teaching," in The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism (Cambridge University Press, 1996, 2003), pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Adams, "Romanitas and the Latin Language," p. 199; Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, pp. 5, 7.

Bibliography

Books

Monographs

- Adams, J.N. Bilingualism and the Latin Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Anderson, Graham The Second Sophistic: A Cultural Phenomenon in the Roman Empire. Routledge, 1993.

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. University of California Press, 2000.

- Clackson, James; Horrocks, Geoffrey. The Blackwell History of the Latin Language. Blackwell, 2007, 2011.

- Goodman, Martin Welsh. Mission and Conversion: Proselytizing in the Religious History of the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Herman, József. Vulgar Latin. Translated by Roger Wright, based on the original 1975 publication in French. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000.

- Millar, Fergus. A Greek Roman Empire: Power and Belief under Theodosius II (408–450). University of California Press, 2006.

- Mullen, Alex. Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean: Multilingualism and Multiple Identities in the Iron Age and Roman Periods. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Treadgold, Warren. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press, 1997.

By multiple contributors

- Apologetics in the Roman Empire: Pagans, Jews, and Christians. Edited by Mark Edwards, Martin Goodman, and Simon Price, with Christopher Rowland. Oxford University Press, 1999.

- A Companion to the Latin Language. Edited by James Clackson. Blackwell, 2011.

- Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds. Edited by Alex Mullen. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- The Oxford Handbook of the Literatures of the Roman Empire. Edited by Daniel L. Selden and Phiroze Vasunia. Oxford University Press (most of the chapters are available online here).

Articles

- Adams, J.N. "Romanitas and the Latin Language." Classical Quarterly 53.1 (2003) 184–205. JSTOR 3556490

- MacMullen, Ramsey. "Provincial Languages in the Roman Empire." American Journal of Philology 87.1 (1966) 1–17. JSTOR 292973

- Millar, Fergus. "Local Cultures in the Roman Empire: Libyan, Punic and Latin in Roman Africa." Journal of Roman Studies 58 (1968) 126–134. JSTOR 299702

- Moatti, Claudia. "Translation, Migration, and Communication in the Roman Empire: Three Aspects of Movement in History." Classical Antiquity 25.1 (2006) 109–140. JSTOR 10.1525/ca.2006.25.1.109

- Rance, Philip. "The De Militari Scientia or Müller Fragment as a Philological Resource. Latin in the East Roman Army and Two New Loanwords in Greek: palmarium and *recala." Glotta 86 (2010) 63–92. JSTOR 41219881

|