Social:Optimality Theory

In linguistics, Optimality Theory (frequently abbreviated OT; the term is normally capitalized by convention) is a linguistic model proposing that the observed forms of language arise from the optimal satisfaction of conflicting constraints. OT differs from other approaches to phonological analysis, such as autosegmental phonology and linear phonology (SPE), which typically use rules rather than constraints. OT models grammars as systems that provide mappings from inputs to outputs; typically, the inputs are conceived of as underlying representations, and the outputs as their surface realizations.

In linguistics, Optimality Theory has its origin in a talk given by Alan Prince and Paul Smolensky in 1991[1] which was later developed in an article by the same authors in 1993.[2]

Theory

There are three basic components of the theory:

- Generator (Template:Sc1) takes an input, and generates the list of possible outputs, or candidates,

- Constraint component (Template:Sc1) provides the criteria, in the form of strictly ranked violable constraints, used to decide between candidates, and

- Evaluator (Template:Sc1) chooses the optimal candidate based on the constraints, and this candidate is the output.

Optimality Theory assumes that these components are universal. Differences in grammars reflect different rankings of the universal constraint set, Template:Sc1. Part of language acquisition can then be described as the process of adjusting the ranking of these constraints.

Optimality Theory as applied to language was originally proposed by the linguists Alan Prince and Paul Smolensky in 1991, and later expanded by Prince and John J. McCarthy. Although much of the interest in Optimality Theory has been associated with its use in phonology, the area to which Optimality Theory was first applied, the theory is also applicable to other subfields of linguistics (e.g. syntax and semantics).

Optimality Theory is like other theories of generative grammar in its focus on the investigation of universal principles, linguistic typology and language acquisition.

Optimality Theory also has roots in neural network research. It arose in part as an alternative to the connectionist theory of Harmonic Grammar, developed in 1990 by Géraldine Legendre, Yoshiro Miyata and Paul Smolensky. Variants of Optimality Theory with connectionist-like weighted constraints continue to be pursued in more recent work (Pater 2009).

Input and Template:Sc1: the candidate set

Optimality Theory supposes that there are no language-specific restrictions on the input. This is called richness of the base. Every grammar can handle every possible input. For example, a language without complex clusters must be able to deal with an input such as /flask/. Languages without complex clusters differ on how they will resolve this problem; some will epenthesize (e.g. [falasak], or [falasaka] if all codas are banned) and some will delete (e.g. [fas], [fak], [las], [lak]).

Template:Sc1 is free to generate any number of output candidates, however much they deviate from the input. This is called freedom of analysis. The grammar (ranking of constraints) of the language determines which of the candidates will be assessed as optimal by Template:Sc1.[3]

Template:Sc1: the constraint set

In Optimality Theory, every constraint is universal. Template:Sc1 is the same in every language. There are two basic types of constraints:

- Faithfulness constraints require that the observed surface form (the output) match the underlying or lexical form (the input) in some particular way; that is, these constraints require identity between input and output forms.

- Markedness constraints impose requirements on the structural well-formedness of the output.

Each plays a crucial role in the theory. Markedness constraints motivate changes from the underlying form, and faithfulness constraints prevent every input from being realized as some completely unmarked form (such as [ba]).

The universal nature of Template:Sc1 makes some immediate predictions about language typology. If grammars differ only by having different rankings of Template:Sc1, then the set of possible human languages is determined by the constraints that exist. Optimality Theory predicts that there cannot be more grammars than there are permutations of the ranking of Template:Sc1. The number of possible rankings is equal to the factorial of the total number of constraints, thus giving rise to the term factorial typology. However, it may not be possible to distinguish all of these potential grammars, since not every constraint is guaranteed to have an observable effect in every language. Two total orders on the constraints of Template:Sc1 could generate the same range of input–output mappings, but differ in the relative ranking of two constraints which do not conflict with each other. Since there is no way to distinguish these two rankings they are said to belong to the same grammar. A grammar in OT is equivalent to an antimatroid (Merchant & Riggle 2016). If rankings with ties are allowed, then the number of possibilities is an ordered Bell number rather than a factorial, allowing a significantly larger number of possibilities.[4]

Faithfulness constraints

McCarthy & Prince (1995) propose three basic families of faithfulness constraints:

- Template:Sc1 prohibits deletion (from "maximal").

- Template:Sc1 prohibits epenthesis (from "dependent").

- Template:Sc1(F) prohibits alteration to the value of feature F (from "identical").

Each of the constraints' names may be suffixed with "-IO" or "-BR", standing for input/output and base/reduplicant, respectively—the latter of which is used in analysis of reduplication—if desired. F in Template:Sc1(F) is substituted by the name of a distinctive feature, as in Template:Sc1(voice).

Template:Sc1 and Template:Sc1 replace Template:Sc1 and Template:Sc1 proposed by Prince & Smolensky (1993), which stated "underlying segments must be parsed into syllable structure" and "syllable positions must be filled with underlying segments", respectively.[5][6] Template:Sc1 and Template:Sc1 serve essentially the same functions as Template:Sc1 and Template:Sc1, but differ in that they evaluate only the output and not the relation between the input and output, which is rather characteristic of markedness constraints.[7] This stems from the model adopted by Prince & Smolensky known as containment theory, which assumes the input segments unrealized by the output are not removed but rather "left unparsed" by a syllable.[8] The model put forth by McCarthy & Prince (1995, 1999), known as correspondence theory, has since replaced it as the standard framework.[6]

McCarthy & Prince (1995) also propose:

- Template:Sc1, violated when a word- or morpheme-internal segment is deleted (from "input-contiguity");

- Template:Sc1, violated when a segment is inserted word- or morpheme-internally (from "output-contiguity");

- Template:Sc1, violated when the order of some segments is changed (i.e. prohibits metathesis);

- Template:Sc1, violated when two or more segments are realized as one (i.e. prohibits fusion); and

- Template:Sc1, violated when a segment is realized as multiple segments (i.e. prohibits unpacking or vowel breaking—opposite of Template:Sc1).

Markedness constraints

Markedness constraints introduced by Prince & Smolensky (1993) include:

| Name | Statement | Other names |

|---|---|---|

| Syllables must have nuclei. | ||

| Syllables must have no codas. | ||

| Syllables must have onsets. | ||

| A nuclear segment must be more sonorous than another (from "harmonic nucleus"). | ||

| A syllable must be V, CV or VC. | ||

| Coda consonants cannot have place features that are not shared by an onset consonant. | ||

| A word-final syllable (or foot) must not bear stress. | ||

| A foot must be two syllables (or moras). | ||

| Light syllables must not be stressed. | ||

| WSP | Heavy syllables must be stressed (from "weight-to-stress principle"). |

Precise definitions in literature vary. Some constraints are sometimes used as a "cover constraint", standing in for a set of constraints that are not fully known or important.[9]

Some markedness constraints are context-free and others are context-sensitive. For example, *Vnasal states that vowels must not be nasal in any position and is thus context-free, whereas *VoralN states that vowels must not be oral when preceding a tautosyllabic nasal and is thus context-sensitive.[10]

Alignment constraints

Local conjunctions

Two constraints may be conjoined as a single constraint, called a local conjunction, which gives only one violation each time both constraints are violated within a given domain, such as a segment, syllable or word. For example, [[[:Template:Sc1]]]segment is violated once per voiced obstruent in a coda ("VOP" stands for "voiced obstruent prohibition"), and may be equivalently written as Template:Sc1.[11][12] Local conjunctions are used as a way of circumventing the problem of phonological opacity that arises when analyzing chain shifts.[11]

Template:Sc1: definition of optimality

Given two candidates, A and B, A is better, or more "harmonic", than B on a constraint if A incurs fewer violations than B. Candidate A is more harmonic than B on an entire constraint hierarchy if A incurs fewer violations of the highest-ranked constraint distinguishing A and B. A is "optimal" in its candidate set if it is better on the constraint hierarchy than all other candidates.

For example, given the constraints C1, C2, and C3, where C1 dominates C2, which dominates C3 (C1 ≫ C2 ≫ C3), A is optimal if it does better than B on the highest ranking constraint which assigns them a different number of violations. If A and B tie on C1, but A does better than B on C2, A is optimal, even if A has however many more violations of C3 than B does. This comparison is often illustrated with a tableau. The pointing finger marks the optimal candidate, and each cell displays an asterisk for each violation for a given candidate and constraint. Once a candidate does worse than another candidate on the highest ranking constraint distinguishing them, it incurs a fatal violation (marked in the tableau by an exclamation mark and by shaded cells for the lower-ranked constraints). Once a candidate incurs a fatal violation, it cannot be optimal, even if it outperforms the other candidates on the rest of Template:Sc1.

| Input | Template:Sc1 1 | Template:Sc1 2 | Template:Sc1 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. ☞ | Candidate A | * | * | *** |

| b. | Candidate B | * | **! | |

Other notational conventions include dotted lines separating columns of unranked or equally ranked constraints, a check mark ✔ in place of a finger in tentatively ranked tableaux (denoting harmonic but not conclusively optimal), and a circled asterisk ⊛ denoting a violation by a winner; in output candidates, the angle brackets ⟨ ⟩ denote segments elided in phonetic realization, and □ and □́ denote an epenthetic consonant and vowel, respectively.[13] The "much greater than" sign ≫ (sometimes the nested ⪢) denotes the domination of a constraint over another ("C1 ≫ C2" = "C1 dominates C2") while the "succeeds" operator ≻ denotes superior harmony in comparison of output candidates ("A ≻ B" = "A is more harmonic than B").[14]

Constraints are ranked in a hierarchy of strict domination. The strictness of strict domination means that a candidate which violates only a high-ranked constraint does worse on the hierarchy than one that does not, even if the second candidate fared worse on every other lower-ranked constraint. This also means that constraints are violable; the winning (i.e. the most harmonic) candidate need not satisfy all constraints, as long as for any rival candidate that does better than the winner on some constraint, there is a higher-ranked constraint on which the winner does better than that rival. Within a language, a constraint may be ranked high enough that it is always obeyed; it may be ranked low enough that it has no observable effects; or, it may have some intermediate ranking. The term the emergence of the unmarked describes situations in which a markedness constraint has an intermediate ranking, so that it is violated in some forms, but nonetheless has observable effects when higher-ranked constraints are irrelevant.

An early example proposed by McCarthy & Prince (1994) is the constraint Template:Sc1, which prohibits syllables from ending in consonants. In Balangao, Template:Sc1 is not ranked high enough to be always obeyed, as witnessed in roots like taynan (faithfulness to the input prevents deletion of the final /n/). But, in the reduplicated form ma-tayna-taynan 'repeatedly be left behind', the final /n/ is not copied. Under McCarthy & Prince's analysis, this is because faithfulness to the input does not apply to reduplicated material, and Template:Sc1 is thus free to prefer ma-tayna-taynan over hypothetical ma-taynan-taynan (which has an additional violation of Template:Sc1).

Some optimality theorists prefer the use of comparative tableaux, as described in Prince (2002b). Comparative tableaux display the same information as the classic or "flyspeck" tableaux, but the information is presented in such a way that it highlights the most crucial information. For instance, the tableau above would be rendered in the following way.

| Template:Sc1 1 | Template:Sc1 2 | Template:Sc1 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A ~ B | e | W | L |

Each row in a comparative tableau represents a winner–loser pair, rather than an individual candidate. In the cells where the constraints assess the winner–loser pairs, "W" is placed if the constraint in that column prefers the winner, "L" if the constraint prefers the loser, and "e" if the constraint does not differentiate between the pair. Presenting the data in this way makes it easier to make generalizations. For instance, in order to have a consistent ranking some W must dominate all L's. Brasoveanu and Prince (2005) describe a process known as fusion and the various ways of presenting data in a comparative tableau in order to achieve the necessary and sufficient conditions for a given argument.

Example

As a simplified example, consider the manifestation of the English plural:

- /dɒɡ/ + /z/ → [dɒɡz] (dogs)

- /kæt/ + /z/ → [kæts] (cats)

- /dɪʃ/ + /z/ → [dɪʃɪz] (dishes)

Also consider the following constraint set, in descending order of domination:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Markedness | *SS | Two successive sibilants are prohibited. One violation for every pair of adjacent sibilants in the output. |

| Template:Sc1(Voice) | Output segments agree in specification of [±voice]. One violation for every pair of adjacent obstruents in the output which disagree in voicing. | |

| Faithfulness | Template:Sc1 | Maximizes all input segments in the output. One violation for each segment in the input that does not appear in the output. This constraint prevents deletion. |

| Template:Sc1 | Output segments are dependent on having an input correspondent. One violation for each segment in the output that does not appear in the input. This constraint prevents insertion. | |

| Template:Sc1(Voice) | Maintains the identity of the [±voice] specification. One violation for each segment that differs in voicing between the input and output. |

| /dɒɡ/ + /z/ | *SS | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. ☞ | dɒɡz | |||||

| b. | dɒɡs | *! | * | |||

| c. | dɒɡɪz | *! | ||||

| d. | dɒɡɪs | *! | * | |||

| e. | dɒɡ | *! | ||||

| /kæt/ + /z/ | *SS | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. | kætz | *! | ||||

| b. ☞ | kæts | * | ||||

| c. | kætɪz | *! | ||||

| d. | kætɪs | *! | * | |||

| e. | kæt | *! | ||||

| /dɪʃ/ + /z/ | *SS | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. | dɪʃz | *! | * | |||

| b. | dɪʃs | *! | * | |||

| c. ☞ | dɪʃɪz | * | ||||

| d. | dɪʃɪs | * | *! | |||

| e. | dɪʃ | *! | ||||

No matter how the constraints are re-ordered, the allomorph [ɪs] will always lose to [ɪz]. This is called harmonic bounding. The violations incurred by the candidate [dɒɡɪz] are a subset of the violations incurred by [dɒɡɪs]; specifically, if you epenthesize a vowel, changing the voicing of the morpheme is a gratuitous violation of constraints. In the /dɒɡ/ + /z/ tableau, there is a candidate [dɒɡz] which incurs no violations whatsoever. Within the constraint set of the problem, [dɒɡz] harmonically bounds all other possible candidates. This shows that a candidate does not need to be a winner in order to harmonically bound another candidate.

The tableaux from above are repeated below using the comparative tableaux format.

| /dɒɡ/ + /z/ | *SS | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dɒɡz ~ dɒɡs | e | W | e | e | W |

| dɒɡz ~ dɒɡɪz | e | e | e | W | e |

| dɒɡz ~ dɒɡɪs | e | e | e | W | W |

| dɒɡz ~ dɒɡ | e | e | W | e | e |

| /kæt/ + /z/ | *SS | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kæts ~ kætz | e | W | e | e | L |

| kæts ~ kætɪz | e | e | e | W | L |

| kæts ~ kætɪs | e | e | e | W | e |

| kæts ~ kæt | e | e | W | e | L |

| /dɪʃ/ + /z/ | *SS | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 | Template:Sc1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dɪʃɪz ~ dɪʃz | W | W | e | L | e |

| dɪʃɪz ~ dɪʃs | W | e | e | L | W |

| dɪʃɪz ~ dɪʃɪs | e | e | e | e | W |

| dɪʃɪz ~ dɪʃ | e | e | W | L | e |

From the comparative tableau for /dɒɡ/ + /z/, it can be observed that any ranking of these constraints will produce the observed output [dɒɡz]. Because there are no loser-preferring comparisons, [dɒɡz] wins under any ranking of these constraints; this means that no ranking can be established on the basis of this input.

The tableau for /kæt/ + /z/ contains rows with a single W and a single L. This shows that Template:Sc1, Template:Sc1, and Template:Sc1 must all dominate Template:Sc1; however, no ranking can be established between those constraints on the basis of this input. Based on this tableau, the following ranking has been established

The tableau for /dɪʃ/ + /z/ shows that several more rankings are necessary in order to predict the desired outcome. The first row says nothing; there is no loser-preferring comparison in the first row. The second row reveals that either *SS or Template:Sc1 must dominate Template:Sc1, based on the comparison between [dɪʃɪz] and [dɪʃz]. The third row shows that Template:Sc1 must dominate Template:Sc1. The final row shows that either *SS or Template:Sc1 must dominate Template:Sc1. From the /kæt/ + /z/ tableau, it was established that Template:Sc1 dominates Template:Sc1; this means that *SS must dominate Template:Sc1.

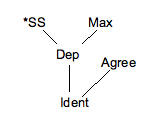

So far, the following rankings have been shown to be necessary:

- *SS, Template:Sc1 ≫ Template:Sc1 ≫ Template:Sc1

While it is possible that Template:Sc1 can dominate Template:Sc1, it is not necessary; the ranking given above is sufficient for the observed for [dɪʃɪz] to emerge.

When the rankings from the tableaux are combined, the following ranking summary can be given:

- *SS, Template:Sc1 ≫ Template:Sc1, Template:Sc1 ≫ Template:Sc1

- or

- *SS, Template:Sc1, Template:Sc1 ≫ Template:Sc1 ≫ Template:Sc1

There are two possible places to put Template:Sc1 when writing out rankings linearly; neither is truly accurate. The first implies that *SS and Template:Sc1 must dominate Template:Sc1, and the second implies that Template:Sc1 must dominate Template:Sc1. Neither of these are truthful, which is a failing of writing out rankings in a linear fashion like this. These sorts of problems are the reason why most linguists utilize a lattice graph to represent necessary and sufficient rankings, as shown below.

A diagram that represents the necessary rankings of constraints in this style is a Hasse diagram.

Criticism

Optimality Theory has attracted substantial amounts of criticism, most of which is directed at its application to phonology (rather than syntax or other fields).[15][16][17][18][19][20]

It is claimed that Optimality Theory cannot account for phonological opacity (see Idsardi 2000, for example). In derivational phonology, effects that are inexplicable at the surface level but are explainable through "opaque" rule ordering may be seen; but in Optimality Theory, which has no intermediate levels for rules to operate on, these effects are difficult to explain.

For example, in Quebec French, high front vowels triggered affrication of /t/, (e.g. /tipik/ → [tˢpɪk]), but the loss of high vowels (visible at the surface level) has left the affrication with no apparent source. Derivational phonology can explain this by stating that vowel syncope (the loss of the vowel) "counterbled" affrication—that is, instead of vowel syncope occurring and "bleeding" (i.e. preventing) affrication, it says that affrication applies before vowel syncope, so that the high vowel is removed and the environment destroyed which had triggered affrication. Such counterbleeding rule orderings are therefore termed opaque (as opposed to transparent), because their effects are not visible at the surface level.

The opacity of such phenomena finds no straightforward explanation in Optimality Theory, since intermediate forms are not accessible (constraints refer only to the surface form and/or the underlying form). There have been a number of proposals designed to account for it, but most of the proposals significantly alter Optimality Theory's basic architecture and therefore tend to be highly controversial. Frequently, such alterations add new types of constraints (which are not universal faithfulness or markedness constraints), or change the properties of Template:Sc1 (such as allowing for serial derivations) or Template:Sc1. Examples of these include John J. McCarthy's sympathy theory and candidate chains theory, among many others.

A relevant issue is the existence of circular chain shifts, i.e. cases where input /X/ maps to output [Y], but input /Y/ maps to output [X]. Many versions of Optimality Theory predict this to be impossible (see Moreton 2004, Prince 2007).

Optimality Theory is also criticized as being an impossible model of speech production/perception: computing and comparing an infinite number of possible candidates would take an infinitely long time to process. Idsardi (2006) argues this position, though other linguists dispute this claim on the grounds that Idsardi makes unreasonable assumptions about the constraint set and candidates, and that more moderate instantiations of Optimality Theory do not present such significant computational problems (see Kornai (2006) and Heinz, Kobele & Riggle (2009)). Another common rebuttal to this criticism of Optimality Theory is that the framework is purely representational. In this view, Optimality Theory is taken to be a model of linguistic competence and is therefore not intended to explain the specifics of linguistic performance.[21][22]

Another objection to Optimality Theory is that it is not technically a theory, in that it does not make falsifiable predictions. The source of this issue may be in terminology: the term theory is used differently here than in physics, chemistry, and other sciences. Specific instantiations of Optimality Theory may make falsifiable predictions, in the same way specific proposals within other linguistic frameworks can. What predictions are made, and whether they are testable, depends on the specifics of individual proposals (most commonly, this is a matter of the definitions of the constraints used in an analysis). Thus, Optimality Theory as a framework is best described[according to whom?] as a scientific paradigm.[23]

Theories within Optimality Theory

In practice, implementations of Optimality Theory often assume other related concepts, such as the syllable, the mora, or feature geometry. Completely distinct from these, there are sub-theories which have been proposed entirely within Optimality Theory, such as positional faithfulness theory, correspondence theory (McCarthy & Prince 1995), sympathy theory, and a number of theories of learnability, most notably by Bruce Tesar. There are also a range of theories specifically about Optimality Theory. These are concerned with issues like the possible formulations of constraints, and constraint interactions other than strict domination.

Use outside of phonology

Optimality Theory is most commonly associated with the field of phonology, but has also been applied to other areas of linguistics. Jane Grimshaw, Geraldine Legendre and Joan Bresnan have developed instantiations of the theory within syntax.[24][25] Optimality theoretic approaches are also relatively prominent in morphology (and the morphology–phonology interface in particular).[26][27]

Notes

- ↑ "Optimality". Proceedings of the talk given at Arizona Phonology Conference, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ.

- ↑ Prince, Alan, and Smolensky, Paul (1993) "Optimality Theory: Constraint interaction in generative grammar." Technical Report CU-CS-696-93, Department of Computer Science, University of Colorado at Boulder.

- ↑ Kager (1999), p. 20.

- ↑ Ellison, T. Mark; Klein, Ewan (2001), "Review: The Best of All Possible Words (review of Optimality Theory: An Overview, Archangeli, Diana & Langendoen, D. Terence, eds., Blackwell, 1997)", Journal of Linguistics 37 (1): 127–143.

- ↑ Prince & Smolensky (1993), p. 94.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 McCarthy (2008), p. 27.

- ↑ McCarthy (2008), p. 209.

- ↑ Kager (1999), pp. 99–100.

- ↑ McCarthy (2008), p. 224.

- ↑ Kager (1999), pp. 29–30.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kager (1999), pp. 392–400.

- ↑ McCarthy (2008), pp. 214–20.

- ↑ Tesar & Smloensky (1998), pp. 230–1, 239.

- ↑ McCarthy (2001), p. 247.

- ↑ Chomsky (1995)

- ↑ Dresher (1996)

- ↑ Hale & Reiss (2008)

- ↑ Halle (1995)

- ↑ Idsardi (2000)

- ↑ Idsardi (2006)

- ↑ Kager, René (1999). Optimality Theory. Section 1.4.4: Fear of infinity, pp. 25–27.

- ↑ Prince, Alan and Paul Smolensky. (2004): Optimality Theory: Constraint Interaction in Generative Grammar. Section 10.1.1: Fear of Optimization, pp. 215–217.

- ↑ de Lacy (editor). (2007). The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology, p. 1.

- ↑ McCarthy, John (2001). A Thematic Guide to Optimality Theory, Chapter 4: Connections of Optimality Theory.

- ↑ Legendre, Grimshaw & Vikner (2001)

- ↑ Trommer (2001)

- ↑ Wolf (2008)

References

- Brasoveanu, Adrian, and Alan Prince (2005). Ranking & Necessity. ROA-794.

- Chomsky (1995). The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Dresher, Bezalel Elan (1996): The Rise of Optimality Theory in First Century Palestine. GLOT International 2, 1/2, January/February 1996, page 8 (a humorous introduction for novices)

- Hale, Mark, and Charles Reiss (2008). The Phonological Enterprise. Oxford University Press.

- Halle, Morris (1995). Feature Geometry and Feature Spreading. Linguistic Inquiry 26, 1-46.

- Heinz, Jeffrey, Greg Kobele, and Jason Riggle (2009). Evaluating the Complexity of Optimality Theory. Linguistic Inquiry 40, 277-288.

- Idsardi, William J. (2006). A Simple Proof that Optimality Theory is Computationally Intractable. Linguistic Inquiry 37:271-275.

- Idsardi, William J. (2000). Clarifying opacity. The Linguistic Review 17:337-50.

- Kager, René (1999). Optimality Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kornai, Andras (2006). Is OT NP-hard?. ROA-838.

- Legendre, Géraldine, Jane Grimshaw and Sten Vikner. (2001). Optimality-theoretic syntax. MIT Press.

- McCarthy, John (2001). A Thematic Guide to Optimality Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McCarthy, John (2007). Hidden Generalizations: Phonological Opacity in Optimality Theory. London: Equinox.

- McCarthy, John (2008). Doing Optimality Theory: Applying Theory to Data. Blackwell.

- McCarthy, John and Alan Prince (1993): Prosodic Morphology: Constraint Interaction and Satisfaction. Rutgers University Center for Cognitive Science Technical Report 3.

- McCarthy, John and Alan Prince (1994): The Emergence of the Unmarked: Optimality in Prosodic Morphology. Proceedings of NELS.

- McCarthy, John J. & Alan Prince. (1995). Faithfulness and reduplicative identity. In J. Beckman, L. W. Dickey, & S. Urbanczyk (Eds.), University of Massachusetts occasional papers in linguistics (Vol. 18, pp. 249–384). Amherst, MA: GLSA Publications.

- Merchant, Nazarre & Jason Riggle. (2016) OT grammars, beyond partial orders: ERC sets and antimatroids. Nat Lang Linguist Theory, 34: 241. doi:10.1007/s11049-015-9297-5

- Moreton, Elliott (2004): Non-computable Functions in Optimality Theory. Ms. from 1999, published 2004 in John J. McCarthy (ed.), Optimality Theory in Phonology.

- Pater, Joe. (2009). Weighted Constraints in Generative Linguistics. "Cognitive Science" 33, 999-1035.

- Prince, Alan (2007). The Pursuit of Theory. In Paul de Lacy, ed., Cambridge Handbook of Phonology.

- Prince, Alan (2002a). Entailed Ranking Arguments. ROA-500.

- Prince, Alan (2002b). Arguing Optimality. In Coetzee, Andries, Angela Carpenter and Paul de Lacy (eds). Papers in Optimality Theory II. GLSA, UMass. Amherst. ROA-536.

- Prince, Alan and Paul Smolensky. (1993/2002/2004): Optimality Theory: Constraint Interaction in Generative Grammar. Blackwell Publishers (2004) [1](2002). Technical Report, Rutgers University Center for Cognitive Science and Computer Science Department, University of Colorado at Boulder (1993).

- Tesar, Bruce and Paul Smolensky (1998). Learnability in Optimality Theory. Linguistic Inquiry 29(2): 229–268.

- Trommer, Jochen. (2001). Distributed Optimality. PhD dissertation, Universität Potsdam.

- Wolf, Matthew. (2008). Optimal Interleaving: Serial Phonology-Morphology Interaction in a Constraint-Based Model. PhD dissertation, University of Massachusetts. ROA-996.

External links

- Rutgers University Optimality Archive

- Optimality Theory and the Three Laws of Robotics

- OT Syntax: an interview with Jane Grimshaw