Social:Proportional approval voting

Proportional approval voting (PAV) is a proportional electoral system for multiwinner elections. It is an extension of the D'Hondt method of apportionment[1][2] that additionally allows for personal votes (voters vote for candidates, not for a party list). The voters vote via approval ballots where each voter marks those candidates that the voter finds acceptable.

History

PAV is a special case of Thiele's voting rules, proposed by Thorvald N. Thiele.[3][4][5] It was used in combination with ranked voting in the early 20th century in Sweden, for example between 1909 and 1921 for distributing seats within parties, and in local elections.[4] After 1921 it was replaced by Phragmén's rules. PAV was rediscovered by Forest Simmons in 2001[6] who gave it the name "proportional approval voting".

Definition

PAV selects a committee of a fixed desired size with the highest score, where scores are calculated according to the following formula. Given a committee [math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math], for each voter we check how many candidates in the committee the voter approves. Assuming that the voter voted for [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] candidates in [math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math], the voter contributes to the score of [math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math] the value of the [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math]-th harmonic number, that is:[6][7]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{H}(r) = 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \cdots + \frac{1}{r} \text{.} }[/math]

The score of [math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math] is calculated as the sum of the scores garnered from all the voters.

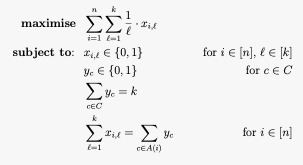

Formally, assume we have a set of candidates [math]\displaystyle{ C = \{c_1, c_2, \ldots, c_m\} }[/math], a set of voters [math]\displaystyle{ N = \{1, 2, \ldots, n\} }[/math], and a committee size [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ A_i }[/math] denote the set of candidates approved by voter [math]\displaystyle{ i \in N }[/math]. The PAV score of a committee [math]\displaystyle{ W \subseteq C }[/math] with size [math]\displaystyle{ |W| = k }[/math] is defined as [math]\displaystyle{ \textstyle \mathrm{sc}_{\mathrm{PAV}}(W) = \sum_{i=1}^{n}\mathrm{H}(|A_i \cap W|) }[/math]. PAV select the committee [math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math] with the maximal score.

Example 1

Assume 2 seats to be filled, and there are four candidates: Andrea (A), Brad (B), Carter (C), and Delilah (D), and 30 voters. The ballots are:

- 5 voters voted for A and B

- 17 voters voted for A and C

- 8 voters voted for D

There are 6 possible results: AB, AC, AD, BC, BD, and CD.

| AB | AC | AD | BC | BD | CD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| score from the 5 voters voting for AB | [math]\displaystyle{ 5\cdot \left(1 + \tfrac{1}{2}\right) = 7.5 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 5\cdot 1 = 5 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 5\cdot 1 = 5 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 5\cdot 1 = 5 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 5\cdot 1 = 5 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 5\cdot 0 = 0 }[/math] |

| score from the 17 voters voting for AC | [math]\displaystyle{ 17\cdot 1 = 17 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 17\cdot \left(1 + \tfrac{1}{2}\right) = 25.5 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 17\cdot 1 = 17 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 17\cdot 1 = 17 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 17\cdot 0 = 0 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 17\cdot 1 = 17 }[/math] |

| score from the 8 voters voting for D | [math]\displaystyle{ 8\cdot 0 = 0 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 8\cdot 0 = 0 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 8\cdot 1 = 8 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 8\cdot 0 = 0 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 8\cdot 1 = 8 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 8\cdot 1 = 8 }[/math] |

| Total score | 24.5 | 30.5 | 30 | 22 | 13 | 25 |

Andrea and Carter are elected.

Note that Simple Approval shows that Andrea has 22 votes, Carter has 17 votes, Delilah has 8 votes and Brad has 5 votes. In this case, the PAV selection of Andrea and Carter is coincident with the Simple Approval sequence. However, if the above votes are changed slightly so that A and C receive 16 votes and D receives 9 votes, then Andrea and Delilah are elected since the A and C score is now 29 while the A and D score remains at 30. Also, the sequence created by using Simple Approval remains unchanged. This shows that PAV can give results that are incompatible with the method which simply follows the sequence implied by Simple Approval.

Example 2

Assume there are 10 seats to be selected, and there are three groups of candidates: red, blue, and green candidates. There are 100 voters:

- 60 voters voted for all blue candidates,

- 30 voters voted for all red candidates,

- 10 voters voted for all green candidates.

In this case PAV would select 6 blue, 3 red, and 1 green candidate. The score of such a committee would be[math]\displaystyle{ 60 \cdot \mathrm{H}(6) + 30 \cdot \mathrm{H}(3) + 10 \cdot \mathrm{H}(1) = 60 \cdot \left(1 + \tfrac{1}{2} + \ldots + \tfrac{1}{6} \right) + 30 \cdot \left(1 + \tfrac{1}{2} + \tfrac{1}{3} \right) + 10 \cdot 1 = 147 + 55 + 10 = 212 \text{.} }[/math]All other committees receive a lower score. For example, the score of a committee that consists of only blue candidates would be

- [math]\displaystyle{ 60 \cdot \mathrm{H}(10) + 30 \cdot \mathrm{H}(0) + 10 \cdot \mathrm{H}(0) = 60 \cdot \left(1 + \tfrac{1}{2} + \ldots + \tfrac{1}{10} \right) \approx 175.73 \text{.} }[/math]

In this example, the outcome of PAV is proportional: the number of candidates selected from each group is proportional to the number of voters voting for the group. This is not coincidence: If the candidates form disjoint groups, as in the above example (the groups can be viewed as political parties), and each voter votes exclusively for all of the candidates within a single group, then PAV will act in the same way as the D'Hondt method of party-list proportional representation.[1]

Properties

This section describes axiomatic properties of Proportional Approval Voting.

Committees of size one

In an election with only one winner, PAV operates in exactly the same way as approval voting. That is, it selects the committee consisting of the candidate who is approved by the most voters.

Proportionality

Most systems of proportional representation use party lists. PAV was designed to have both proportional representation and personal votes (voters vote for candidates, not for a party list). It deserves to be called a "proportional" system because if votes turn out to follow a partisan scheme (each voter votes for all candidates from a party and no other) then the system elects a number of candidates in each party that is proportional to the number of voters who chose this party (see Example 2).[1] Further, under mild assumptions (symmetry, continuity and Pareto efficiency), PAV is the only extension of the D'Hondt method that allows personal votes and that satisfies the consistency criterion.[2]

Even if the voters do not follow the partisan scheme, the rule provides proportionality guarantees. For example, PAV satisfies the strong fairness property called extended justified representation,[7] as well as the related property proportional justified representation.[8] It also has optimal proportionality degree.[9][10] All these properties guarantee that any group of voters with cohesive (similar) preferences will be represented by a number of candidates that is at least proportional to the size of the group. PAV is the only method satisfying such properties among all PAV-like optimization methods (that may use numbers other than harmonic numbers in their definition).[7]

The committees returned by PAV might not be in the core.[7][11] However, it guarantees 2-approximation of the core, which is the optimal approximation ratio that can be achieved by a rule satisfying the Pigou–Dalton principle of transfers.[11] Furthermore, PAV satisfies the property of the core if there are sufficiently many similar candidates running in an election.[12]

PAV fails priceability (that is, the choice of PAV cannot be always explained via a process where the voters are endowed with a fixed amount of virtual money, and spend this spend money on buying candidates they like) and fails laminar proportionality.[11] Two alternative rules that satisfy priceability and laminar proportionality, and that have comparably good proportionality-related properties to PAV are the Method of Equal Shares and Phragmén's Sequential Rules.[13] These two alternative methods are also computable in polynomial time, yet they fail Pareto efficiency.

Other properties

Apart from properties pertaining to proportionality, PAV satisfies the following axioms:

- Pareto efficiency,

- Consistency,

- Support monotonicity (if the support of a winning candidate increases, i.e., more voters vote for this candidate, then this candidate remains winning),[14]

- Pigou–Dalton principle.[11]

PAV fails the following properties:

- House monotonicity.[13] Two alternative methods that satisfy house monotonicity and that have comparably good proportionality-related properties to PAV are Sequential Proportional Approval Voting and Phragmén's Sequential Rules.[13] These two alternative methods are also computable in polynomial time, but they fail Pareto efficiency, Consistency, and the Pigou–Dalton principle.[13]

Computation

Computing the winning committee under PAV is NP-hard,[16][17] making it a computationally demanding voting method as the number of candidates and seats increase. Under a brute force approach, if there were m candidates and k seats, then there would be

- [math]\displaystyle{ \binom{m}{k} = \frac{m!}{k! (m-k)!} }[/math]

combinations of candidates to compare with each election.[18] For example, if there were 24 candidates for 4 seats, there would be 10,626 combinations for which we would need to calculate PAV scores. An election requiring this many calculations would necessitate vote counting by computer. For medium-size elections, the outcome of PAV can be computed by using integer programming solvers. The ILP implementation of PAV is part of the Python package abcvoting.[19] When k is fixed (a constant), the brute-force computation of PAV takes polynomial time, i.e. [math]\displaystyle{ O(n m^k) }[/math], where n is the number of voters.

Sequential proportional approval voting is a method that can be considered an approximation of PAV with approximation ratio equal to [math]\displaystyle{ 1 - 1/e \approx 0.63 }[/math], so the PAV score of the resulting committee is at most 37% worse than optimal.[17] This method can be computed in polynomial time, and the election outcome could potentially be determined by hand. Sequential proportional approval voting on its own exhibits good properties and can be used as a full-fledged election system, though formally it fails all the proportionality properties that distinguish PAV. A more complex approach based on randomized rounding gives an approximation ratio of 0.7965.[20] Under standard assumptions in complexity theory, this is the best approximation ratio that can be achieved for PAV in polynomial time.[20] The problem of approximating PAV can be also formulated as the a minimization problem (instead of maximizing [math]\displaystyle{ \textstyle \mathrm{sc}_{\mathrm{PAV}}(W) }[/math] we want to minimize [math]\displaystyle{ \textstyle \sum_{i \in N }\mathrm{H}(k) - \mathrm{sc}_{\mathrm{PAV}}(W) }[/math]), in which case the best known approximation ratio is 2.36.[21]

From the perspective of parameterized complexity, the problem of computing PAV is typically hard, with a few exceptional easy cases.[16][22] The problem is NP-hard even in the two-dimensional spatial model of voting.[23] It is solvable in polynomial time in the case of a single dimension.[15]

Beyond approval committee elections

PAV can be used for voting on an agenda consisting of a number of independent issues, on which yes/no decisions need to be made.[24][25]

Further reading

- Lackner, Martin; Skowron, Piotr (2023). Multi-Winner Voting with Approval Preferences. SpringerBriefs in Intelligent Systems. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-09016-5. ISBN 978-3-031-09015-8.

- Piotr Faliszewski, Piotr Skowron, Arkadii Slinko, Nimrod Talmon (2017-10-26). "Multiwinner Voting: A New Challenge for Social Choice Theory". in Endriss, Ulle (in en). Trends in Computational Social Choice. AI Access. ISBN 978-1-326-91209-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=0qY8DwAAQBAJ&dq=multiwinner++voting+a+new+challenge&pg=PA27.

See also

- Method of Equal Shares

- D'Hondt method

- Sequential proportional approval voting

- Phragmen's voting rules

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 Brill, Markus; Laslier, Jean-François; Skowron, Piotr (2018). "Multiwinner Approval Rules as Apportionment Methods". Journal of Theoretical Politics 30 (3): 358–382. doi:10.1177/0951629818775518.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Lackner, Martin; Skowron, Piotr (2021). "Consistent approval-based multi-winner rules". Journal of Economic Theory 192: 105173. doi:10.1016/j.jet.2020.105173. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022053120301666.

- ↑ Thiele, Thorvald N. (1895). "Om Flerfoldsvalg". Oversigt over Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Forhandlinger: 415–441.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Janson, Svante (2016). "Phragmén's and Thiele's election methods". arXiv:1611.08826 [math.HO].

- ↑ "RangeVoting.org - Optimal proportional representation". https://rangevoting.org/QualityMulti.html.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Kilgour, D. Marc (2010). "Approval Balloting for Multi-winner Elections". Handbook on Approval Voting. Springer. pp. 105–124. ISBN 978-3-642-02839-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=mQBEAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA114.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Aziz, Haris; Brill, Markus; Conitzer, Vincent; Elkind, Edith; Freeman, Rupert; Walsh, Toby (2017). "Justified representation in approval-based committee voting" (in en). Social Choice and Welfare 48 (2): 461–485. doi:10.1007/s00355-016-1019-3. https://ideas.repec.org/a/spr/sochwe/v48y2017i2d10.1007_s00355-016-1019-3.html.

- ↑ Sánchez-Fernández, Luis; Elkind, Edith; Lackner, Martin; Fernández, Norberto; Fisteus, Jesús; Val, Pablo Basanta; Skowron, Piotr (2017-02-10). "Proportional Justified Representation" (in en). Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 31 (1). doi:10.1609/aaai.v31i1.10611. ISSN 2374-3468. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/10611.

- ↑ Aziz, Haris; Elkind, Edith; Huang, Shenwei; Lackner, Martin; Sánchez Fernández, Luis; Skowron, Piotr (2018). "On the Complexity of Extended and Proportional Justified Representation" (in en). Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 32 (1): 902–909. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11478. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/11478.

- ↑ Skowron, Piotr (2021). "Proportionality Degree of Multiwinner Rules" (in en). Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Conference on Economics and Computation. EC-21. pp. 820–840. doi:10.1145/3465456.3467641. ISBN 9781450385541.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Peters, Dominik; Skowron, Piotr (2020). "Proportionality and the Limits of Welfarism". Proceedings of the 21st ACM Conference on Economics and Computation. EC'20. pp. 793–794. doi:10.1145/3391403.3399465. ISBN 9781450379755.

- ↑ Brill, Markus; Gölz, Paul; Peters, Dominik; Schmidt-Kraepelin, Ulrike; Wilker, Kai (2020). "Approval-Based Apportionment". Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 34 (2): 1854–1861. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i02.5553.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Lackner, Martin; Skowron, Piotr (2023). Multi-Winner Voting with Approval Preferences. SpringerBriefs in Intelligent Systems. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-09016-5. ISBN 978-3-031-09015-8.

- ↑ Sánchez Fernández, Luis; Fisteus, Jesús (2019) (in en). Monotonicity axioms in approval-based multi-winner voting rules. pp. 485–493. https://www.ifaamas.org/Proceedings/aamas2019/pdfs/p485.pdf.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Peters, Dominik (2018). Single-Peakedness and Total Unimodularity: New Polynomial-Time Algorithms for Multi-Winner Elections. pp. 1169–1176.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Aziz, Haris; Gaspers, Serge; Gudmundsson, Joachim; Mackenzie, Simon; Mattei, Nicholas; Walsh, Toby (2015). Computational Aspects of Multi-Winner Approval Voting. pp. 107–115. ISBN 978-1-4503-3413-6.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Skowron, Piotr; Faliszewski, Piotr; Lang, Jérôme (2016). "Finding a collective set of items: From proportional multirepresentation to group recommendation". Artificial Intelligence 241: 191–216. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2016.09.003.

- ↑ Plaza, E. (2004). "Technologies for political representation and accountability" (in en).

- ↑ The Python library abcvoting contains several algorithms for computing PAV, including very fast ones based on integer linear programming.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Dudycz, Szymon; Manurangsi, Pasin; Marcinkowski, Jan; Sornat, Krzysztof (2020). "Tight Approximation for Proportional Approval Voting". Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. IJCAI-20. pp. 276–282. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2020/39. ISBN 978-0-9992411-6-5.

- ↑ Byrka, Jaroslaw; Skowron, Piotr; Sornat, Krzysztof (2017). Proportional Approval Voting, Harmonic k-median, and Negative Association. 107. pp. 26:1–26:14. doi:10.4230/LIPIcs.ICALP.2018.26. ISBN 9783959770767.

- ↑ Bredereck, Robert; Faliszewski, Piotr; Kaczmarczyk, Andrzej; Knop, Dusan; Niedermeier, Rolf (2020). "Parameterized Algorithms for Finding a Collective Set of Items". Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 34 (2): 1838–1845. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i02.5551.

- ↑ Godziszewski, Michal; Batko, Pawel; Skowron, Piotr; Faliszewski, Piotr (2021). "An Analysis of Approval-Based Committee Rules for 2D-Euclidean Elections". Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 35 (6): 5448–5455. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i6.16686. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/16686.

- ↑ Conitzer, Vincent; Freeman, Rupert; Shah, Nisarg (2017). "Fair Public Decision Making". Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Economics and Computation. EC'17. pp. 629–646. doi:10.1145/3033274.3085125. ISBN 9781450345279.

- ↑ Freeman, Rupert; Kahng, David; Pennock, Anson (2020). "Proportionality in Approval-Based Elections with a Variable Number of Winners". Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 1. pp. 132–138. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2020/19. ISBN 978-0-9992411-6-5. https://www.ijcai.org/proceedings/2020/19.

External links

- Online tool for computing PAV and other approval-based multi-winner methods

- Python package abcvoting containing an implementation of PAV (pypi)

|