Harmonic number

In mathematics, the n-th harmonic number is the sum of the reciprocals of the first n natural numbers:[1]

Starting from n = 1, the sequence of harmonic numbers begins:

Harmonic numbers are related to the harmonic mean in that the n-th harmonic number is also n times the reciprocal of the harmonic mean of the first n positive integers.

Harmonic numbers have been studied since antiquity and are important in various branches of number theory. They are sometimes loosely termed harmonic series, are closely related to the Riemann zeta function, and appear in the expressions of various special functions.

The harmonic numbers roughly approximate the natural logarithm function[2]: 143 and thus the associated harmonic series grows without limit, albeit slowly. In 1737, Leonhard Euler used the divergence of the harmonic series to provide a new proof of the infinity of prime numbers. His work was extended into the complex plane by Bernhard Riemann in 1859, leading directly to the celebrated Riemann hypothesis about the distribution of prime numbers.

When the value of a large quantity of items has a Zipf's law distribution, the total value of the n most-valuable items is proportional to the n-th harmonic number. This leads to a variety of surprising conclusions regarding the long tail and the theory of network value.

The Bertrand-Chebyshev theorem implies that, except for the case n = 1, the harmonic numbers are never integers.[3]

| n | Harmonic number, Hn | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| expressed as a fraction | decimal | relative size | ||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 3 | /2 | 1.5 | |

| 3 | 11 | /6 | ~1.83333 | |

| 4 | 25 | /12 | ~2.08333 | |

| 5 | 137 | /60 | ~2.28333 | |

| 6 | 49 | /20 | 2.45 | |

| 7 | 363 | /140 | ~2.59286 | |

| 8 | 761 | /280 | ~2.71786 | |

| 9 | 7 129 | /2 520 | ~2.82897 | |

| 10 | 7 381 | /2 520 | ~2.92897 | |

| 11 | 83 711 | /27 720 | ~3.01988 | |

| 12 | 86 021 | /27 720 | ~3.10321 | |

| 13 | 1 145 993 | /360 360 | ~3.18013 | |

| 14 | 1 171 733 | /360 360 | ~3.25156 | |

| 15 | 1 195 757 | /360 360 | ~3.31823 | |

| 16 | 2 436 559 | /720 720 | ~3.38073 | |

| 17 | 42 142 223 | /12 252 240 | ~3.43955 | |

| 18 | 14 274 301 | /4 084 080 | ~3.49511 | |

| 19 | 275 295 799 | /77 597 520 | ~3.54774 | |

| 20 | 55 835 135 | /15 519 504 | ~3.59774 | |

| 21 | 18 858 053 | /5 173 168 | ~3.64536 | |

| 22 | 19 093 197 | /5 173 168 | ~3.69081 | |

| 23 | 444 316 699 | /118 982 864 | ~3.73429 | |

| 24 | 1 347 822 955 | /356 948 592 | ~3.77596 | |

| 25 | 34 052 522 467 | /8 923 714 800 | ~3.81596 | |

| 26 | 34 395 742 267 | /8 923 714 800 | ~3.85442 | |

| 27 | 312 536 252 003 | /80 313 433 200 | ~3.89146 | |

| 28 | 315 404 588 903 | /80 313 433 200 | ~3.92717 | |

| 29 | 9 227 046 511 387 | /2 329 089 562 800 | ~3.96165 | |

| 30 | 9 304 682 830 147 | /2 329 089 562 800 | ~3.99499 | |

| 31 | 290 774 257 297 357 | /72 201 776 446 800 | ~4.02725 | |

| 32 | 586 061 125 622 639 | /144 403 552 893 600 | ~4.05850 | |

| 33 | 53 676 090 078 349 | /13 127 595 717 600 | ~4.08880 | |

| 34 | 54 062 195 834 749 | /13 127 595 717 600 | ~4.11821 | |

| 35 | 54 437 269 998 109 | /13 127 595 717 600 | ~4.14678 | |

| 36 | 54 801 925 434 709 | /13 127 595 717 600 | ~4.17456 | |

| 37 | 2 040 798 836 801 833 | /485 721 041 551 200 | ~4.20159 | |

| 38 | 2 053 580 969 474 233 | /485 721 041 551 200 | ~4.22790 | |

| 39 | 2 066 035 355 155 033 | /485 721 041 551 200 | ~4.25354 | |

| 40 | 2 078 178 381 193 813 | /485 721 041 551 200 | ~4.27854 | |

Identities involving harmonic numbers

By definition, the harmonic numbers satisfy the recurrence relation

The harmonic numbers are connected to the Stirling numbers of the first kind by the relation

The harmonic numbers satisfy the series identities and These two results are closely analogous to the corresponding integral results and

Identities involving π

There are several infinite summations involving harmonic numbers and powers of π:[4]

Calculation

An integral representation given by Euler[5] is

The equality above is straightforward by the simple algebraic identity

Using the substitution x = 1 − u, another expression for Hn is

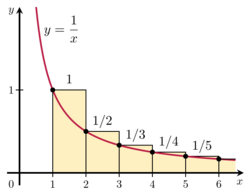

The nth harmonic number is about as large as the natural logarithm of n. The reason is that the sum is approximated by the integral whose value is ln n.

The values of the sequence Hn − ln n decrease monotonically towards the limit where γ ≈ 0.5772156649 is the Euler–Mascheroni constant. The corresponding asymptotic expansion is where Bk are the Bernoulli numbers.

Generating functions

A generating function for the harmonic numbers is where ln(z) is the natural logarithm. An exponential generating function is where Ein(z) is the entire exponential integral. The exponential integral may also be expressed as where Γ(0, z) is the incomplete gamma function.

Arithmetic properties

The harmonic numbers have several interesting arithmetic properties. It is well-known that is an integer if and only if , a result often attributed to Taeisinger.[6] Indeed, using 2-adic valuation, it is not difficult to prove that for the numerator of is an odd number while the denominator of is an even number. More precisely, with some odd integers and .

As a consequence of Wolstenholme's theorem, for any prime number the numerator of is divisible by . Furthermore, Eisenstein[7] proved that for all odd prime number it holds where is a Fermat quotient, with the consequence that divides the numerator of if and only if is a Wieferich prime.

In 1991, Eswarathasan and Levine[8] defined as the set of all positive integers such that the numerator of is divisible by a prime number They proved that for all prime numbers and they defined harmonic primes to be the primes such that has exactly 3 elements.

Eswarathasan and Levine also conjectured that is a finite set for all primes and that there are infinitely many harmonic primes. Boyd[9] verified that is finite for all prime numbers up to except 83, 127, and 397; and he gave a heuristic suggesting that the density of the harmonic primes in the set of all primes should be . Sanna[10] showed that has zero asymptotic density, while Bing-Ling Wu and Yong-Gao Chen[11] proved that the number of elements of not exceeding is at most , for all .

Applications

The harmonic numbers appear in several calculation formulas, such as the digamma function This relation is also frequently used to define the extension of the harmonic numbers to non-integer n. The harmonic numbers are also frequently used to define γ using the limit introduced earlier: although converges more quickly.

In 2002, Jeffrey Lagarias proved[12] that the Riemann hypothesis is equivalent to the statement that is true for every integer n ≥ 1 with strict inequality if n > 1; here σ(n) denotes the sum of the divisors of n.

The eigenvalues of the nonlocal problem on are given by , where by convention , and the corresponding eigenfunctions are given by the Legendre polynomials .[13]

Generalizations

Generalized harmonic numbers

The nth generalized harmonic number of order m is given by

(In some sources, this may also be denoted by or )

The special case m = 0 gives The special case m = 1 reduces to the usual harmonic number:

The limit of as n → ∞ is finite if m > 1, with the generalized harmonic number bounded by and converging to the Riemann zeta function

The smallest natural number k such that kn does not divide the denominator of generalized harmonic number H(k, n) nor the denominator of alternating generalized harmonic number H′(k, n) is, for n=1, 2, ... :

- 77, 20, 94556602, 42, 444, 20, 104, 42, 76, 20, 77, 110, 3504, 20, 903, 42, 1107, 20, 104, 42, 77, 20, 2948, 110, 136, 20, 76, 42, 903, 20, 77, 42, 268, 20, 7004, 110, 1752, 20, 19203, 42, 77, 20, 104, 42, 76, 20, 370, 110, 1107, 20, ... (sequence A128670 in the OEIS)

The related sum occurs in the study of Bernoulli numbers; the harmonic numbers also appear in the study of Stirling numbers.

Some integrals of generalized harmonic numbers are and where A is Apéry's constant ζ(3), and

Every generalized harmonic number of order m can be written as a function of harmonic numbers of order using for example:

A generating function for the generalized harmonic numbers is where is the polylogarithm, and ‹See Tfd›|z| < 1. The generating function given above for m = 1 is a special case of this formula.

A fractional argument for generalized harmonic numbers can be introduced as follows:

For every integer, and integer or not, we have from polygamma functions: where is the Riemann zeta function. The relevant recurrence relation is Some special values arewhere G is Catalan's constant. In the special case that , we get

where is the Hurwitz zeta function. This relationship is used to calculate harmonic numbers numerically.

Multiplication formulas

The multiplication theorem applies to harmonic numbers. Using polygamma functions, we obtain or, more generally,

For generalized harmonic numbers, we have where is the Riemann zeta function.

Hyperharmonic numbers

The next generalization was discussed by J. H. Conway and R. K. Guy in their 1995 book The Book of Numbers.[2]: 258 Let Then the nth hyperharmonic number of order r (r>0) is defined recursively as In particular, is the ordinary harmonic number .

Roman harmonic numbers

The Roman harmonic numbers,[14] named after Steven Roman, were introduced by Daniel Loeb and Gian-Carlo Rota in the context of a generalization of umbral calculus with logarithms.[15] There are many possible definitions, but one of them, for , isandOf course,

If , they satisfyClosed form formulas arewhere is Stirling numbers of the first kind generalized to negative first argument, andwhich was found by Donald Knuth.

In fact, these numbers were defined in a more general manner using Roman numbers and Roman factorials, that include negative values for . This generalization was useful in their study to define Harmonic logarithms.

Harmonic numbers for real and complex values

The formulae given above, are an integral and a series representation for a function that interpolates the harmonic numbers and, via analytic continuation, extends the definition to the complex plane other than the negative integers x. The interpolating function is in fact closely related to the digamma function where ψ(x) is the digamma function, and γ is the Euler–Mascheroni constant. The integration process may be repeated to obtain

The Taylor series for the harmonic numbers is which comes from the Taylor series for the digamma function ( is the Riemann zeta function).

Alternative, asymptotic formulation

There is an asymptotic formulation that gives the same result as the analytic continuation of the integral just described. When seeking to approximate Hx for a complex number x, it is effective to first compute Hm for some large integer m. Use that as an approximation for the value of Hm+x. Then use the recursion relation Hn = Hn−1 + 1/n backwards m times, to unwind it to an approximation for Hx. Furthermore, this approximation is exact in the limit as m goes to infinity.

Specifically, for a fixed integer n, it is the case that

If n is not an integer then it is not possible to say whether this equation is true because we have not yet (in this section) defined harmonic numbers for non-integers. However, we do get a unique extension of the harmonic numbers to the non-integers by insisting that this equation continue to hold when the arbitrary integer n is replaced by an arbitrary complex number x,

Swapping the order of the two sides of this equation and then subtracting them from Hx gives

This infinite series converges for all complex numbers x except the negative integers, which fail because trying to use the recursion relation Hn = Hn−1 + 1/n backwards through the value n = 0 involves a division by zero. By this construction, the function that defines the harmonic number for complex values is the unique function that simultaneously satisfies (1) H0 = 0, (2) Hx = Hx−1 + 1/x for all complex numbers x except the non-positive integers, and (3) limm→+∞ (Hm+x − Hm) = 0 for all complex values x.

This last formula can be used to show that where γ is the Euler–Mascheroni constant or, more generally, for every n we have:

Special values for fractional arguments

There are the following special analytic values for fractional arguments between 0 and 1, given by the integral

More values may be generated from the recurrence relation or from the reflection relation

For example:

Which are computed via Gauss's digamma theorem, which essentially states that for positive integers p and q with p < q

Relation to the Riemann zeta function

Some derivatives of fractional harmonic numbers are given by

And using Maclaurin series, we have for x < 1 that

For fractional arguments between 0 and 1 and for a > 1,

See also

- Watterson estimator

- Tajima's D

- Coupon collector's problem

- Jeep problem

- 100 prisoners problem

- Riemann zeta function

- List of sums of reciprocals

- False discovery rate

- Block-stacking problem

Notes

- ↑ Knuth, Donald (1997) (in en). The Art of Computer Programming (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 75–79. ISBN 0-201-89683-4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 John H., Conway; Richard K., Guy (1995). The book of numbers. Copernicus.

- ↑ Graham, Ronald L.; Knuth, Donald E.; Patashnik, Oren (1994). Concrete Mathematics. Addison-Wesley.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W.. "Harmonic Number" (in en). https://mathworld.wolfram.com/HarmonicNumber.html.

- ↑ Sandifer, C. Edward (2007), How Euler Did It, MAA Spectrum, Mathematical Association of America, p. 206, ISBN 9780883855638, https://books.google.com/books?id=sohHs7ExOsYC&pg=PA206.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. (2003). CRC Concise Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC. pp. 3115. ISBN 978-1-58488-347-0.

- ↑ Eisenstein, Ferdinand Gotthold Max (1850). "Eine neue Gattung zahlentheoretischer Funktionen, welche von zwei Elementen ahhängen und durch gewisse lineare Funktional-Gleichungen definirt werden". Berichte Königl. Preuß. Akad. Wiss. Berlin 15: 36–42.

- ↑ Eswarathasan, Arulappah; Levine, Eugene (1991). "p-integral harmonic sums". Discrete Mathematics 91 (3): 249–257. doi:10.1016/0012-365X(90)90234-9.

- ↑ Boyd, David W. (1994). "A p-adic study of the partial sums of the harmonic series". Experimental Mathematics 3 (4): 287–302. doi:10.1080/10586458.1994.10504298. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.em/1048515811.

- ↑ Sanna, Carlo (2016). "On the p-adic valuation of harmonic numbers". Journal of Number Theory 166: 41–46. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2016.02.020. https://iris.unito.it/bitstream/2318/1622121/1/padicharm.pdf.

- ↑ Chen, Yong-Gao; Wu, Bing-Ling (2017). "On certain properties of harmonic numbers". Journal of Number Theory 175: 66–86. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2016.11.027.

- ↑ Jeffrey Lagarias (2002). "An Elementary Problem Equivalent to the Riemann Hypothesis". Amer. Math. Monthly 109 (6): 534–543. doi:10.2307/2695443.

- ↑ E.O. Tuck (1964). "Some methods for flows past blunt slender bodies". J. Fluid Mech. 18 (4): 619–635. doi:10.1017/S0022112064000453. Bibcode: 1964JFM....18..619T.

- ↑ Sesma, J. (2017). "The Roman harmonic numbers revisited". Journal of Number Theory 180: 544–565. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2017.05.009. ISSN 0022-314X. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jnt.2017.05.009.

- ↑ Loeb, Daniel E; Rota, Gian-Carlo (1989). "Formal power series of logarithmic type". Advances in Mathematics 75 (1): 1–118. doi:10.1016/0001-8708(89)90079-0. ISSN 0001-8708.

References

- Arthur T. Benjamin; Gregory O. Preston; Jennifer J. Quinn (2002). "A Stirling Encounter with Harmonic Numbers". Mathematics Magazine 75 (2): 95–103. doi:10.2307/3219141. http://www.math.hmc.edu/~benjamin/papers/harmonic.pdf. Retrieved 2005-08-08.

- Donald Knuth (1997). "Section 1.2.7: Harmonic Numbers". The Art of Computer Programming. 1: Fundamental Algorithms (Third ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 75–79. ISBN 978-0-201-89683-1.

- Ed Sandifer, How Euler Did It — Estimating the Basel problem (2003)

- "Computer Proofs of a New Family of Harmonic Number Identities". Adv. Appl. Math. 31 (2): 359–378. 2003. doi:10.1016/s0196-8858(03)00016-2. https://www.risc.uni-linz.ac.at/publications/download/risc_200/HarmonicNumberIds.pdf.

- Wenchang Chu (2004). "A Binomial Coefficient Identity Associated with Beukers' Conjecture on Apery Numbers". The Electronic Journal of Combinatorics 11: N15. doi:10.37236/1856. https://www.combinatorics.org/Volume_11/PDF/v11i1n15.pdf.

External links

This article incorporates material from Harmonic number on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

|