Social:Trait activation theory

Trait activation theory is based on a specific model of job performance, and can be considered an elaborated or extended view of personality-job fit. Specifically, it is how an individual expresses their traits when exposed to situational cues related to those traits.[1]: 502 These situational cues may stem from organization, social, and/or task cues.[1] These cues can activate personality traits that are related to job tasks and organizational expectations that the organization values (i.e., job performance). These cues may also elicit trait-related behaviors that are not directly related to job performance.

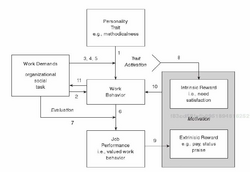

According to the trait-based model of job performance introduced in Tett and Burnett (2003; see Figure 1),[1] trait activation theory suggests three overarching principles (p. 503):

- Traits are expressed in work behavior as responses to trait-relevant situational cues;

- Sources of trait-relevant cues can be grouped into three broad categories or levels: task, social, and organizational; and

- Trait expressive work behavior is distinct from job performance, the latter being defined in the simplest terms as valued work behavior.

Trait activation theory suggests that employees will look for and derive intrinsic satisfaction from a work environment that allows for the easy expression of their unique personality traits. However, the theory stipulates that only in situations where these personality traits are valued on the job (i.e., expression of traits is beneficial to quality job tasks), does "activating" the trait lead to better job performance and the potential for subsequent increased extrinsic rewards (e.g., pay and other benefits). In a nutshell, a workplace environment or job demands that are conducive to the natural and frequent expression of their traits is attractive to people.[2] Trait expression in the workplace is affected by the day-to-day tasks an employee completes, and the specific demands of the job. This idea stems from the concept of operational levels within the workplace. Various responsibilities of an employee determine how they express themselves in the workplace. If a job requires strict adherence to rules and timeliness, that job will lend itself better to an individual to whom these traits come naturally, and may not be ideal for an individual whose personality does not align with the necessities of the job.[3]

For example, the trait, extraversion, is associated with sociability and seeking out others' companionship. If this trait is activated by interaction with customers while a salesperson is performing work tasks related to sales, one might expect such trait activation to result in good job performance and potential subsequent financial bonuses. This is an example of a demand, which is a situational cue that creates a positive outcome when a relevant trait is activated. However, if extraversion is activated on the job by the presence of coworkers and one becomes overly sociable with coworkers, job performance may suffer if this sociability distracts from job tasks. This is an example of a distractor, which is a situational cue that created a negative outcome when a relevant trait is activated.[4] In this example, the organizational cues of whether a high sociability environment is expected between coworkers would influence the strength of the cue and the level of activation. Discretionary cues may activate traits that have a neutral outcome, although discretionary cues do not have a direct impact on work performance, employees are more engaged in fulfilling their workplace duties when given opportunities to activate their discretionary traits. A constraint is a factor that makes a trait less relevant, for example transitioning to a work from home environment from an office may make extraversion less relevant. A releaser is a factor that makes a trait more relevant. A facilitator is a factor that increases the strength of the situational cues that are already present.[4] Note that it is not an assumption of trait activation theory that trait-irrelevant situations result in poor performance. Rather, the theory suggests that a lack of trait activation weakens the trait-performance relationship.[5]

History and development

The principles of trait activation can be traced back as early as 1938, when Henry Murray described that situations elicit trait expression from individuals.[1] Tett, Simonet, Walser, and Brown (2013)[2] summarized the key contributions of others' ideas that preceded and influenced trait activation theory. These are twofold.

First, it is not a question of trait or situation, but that trait and situation work harmoniously together.[6]: 39 Trait activation theory relies heavily on both situational and trait based perspectives on personality. It holds that existing, latent traits are activated by pertinent situations. So, it accepts that both stable traits and situational variance can affect predictable patterns of behavior.[2] This is an extension of Eysenck's work done 20 years before that sought to reconcile the two warring perspectives of trait theory and situationism. This can be summed up as the interactionist perspective, which seeks to solve the person-situation debate by explaining behavior with consideration to both situation and stable traits. Traits remain relatively stable over time creating consistent behavioral inclinations, however they become activated when exposed to a trait relevant situational cue. The behavior associated with the trait will vary depending on the individuals trait level, and the situational strength.[7] Both traits and situations are inseparable factors in human behavior.[8]

Second, situations act as triggers to certain traits that an individual possesses. A certain trait may not choose to manifest itself until a situation arises that necessitates it.[9]: 29 This idea accepts the interactionist perspective, as discussed in the first point, and takes a step further in explaining a way in which traits and situation interact. It is as if traits act passively. They exist as stable qualities, but require the active stimulation of a relevant situation to spurn them into action and influence an individual's behavior.

However, three primary researchers, Robert P. Tett, Hal A. Guterman, and Dawn D. Burnett, are associated with introducing the theory through two focal papers.[10][1] These papers synthesized and expanded the two ideas presented above creating what is known as trait activation theory.

The first of these influential papers is Situation Trait Relevance, Trait Expression, and Cross-Situational Consistency: Testing a Principle of Trait Activation by Robert P. Tett and Hal A. Guterman, published in 2000.[10] This paper explored how trait expression and intention correlated in trait-relevant scenarios versus non-trait-relevant scenarios. Risk taking, complexity, empathy, sociability, and organization were the specific traits this paper focused on. Each trait was measured in both trait-relevant and non-trait relevant scenarios. Scenarios were designed to emulate academic, commercial, domestic, leisure, and work environments. Additionally, scenarios ideally presented mild to moderate activation of traits. Tett and Guterman’s research found that trait-intent correlations were overall highest when the trait being expressed matched the trait scenario, confirming the ideas of trait-activation theory.

The second paper is A Personality Trait-Based Interactionist Model of Job Performance by Robert P. Tett and Dawn D. Burnett.[1] This paper was published in 2003 and expanded upon the findings presented by Tett and Guterman’s paper. This paper introduced 5 more trait relevant scenarios: job demands, distracters, constraits, releasers, and facilitators. These scenarios were developed with the intention of creating scenarios that could act as moderators to personality traits that may interfere with job performance. For example, a “releaser” could be a designated social event to allow an employee high in extraversion fulfill their social needs without interfering with job duties.

Trait activation theory makes an argument for situational specificity; that is, whether a trait leads to better performance depends on the context; or, alternatively, whether the context is relevant for performance depends on the trait.[5]: 1152 Thus, proponents of the theory argue that trait-relevant situations result in better performance than situations that are trait-irrelevant. For example, in a workplace setting, an employee may be assigned to a role that largely contains situations not calculated to stimulate this employee's particular traits. They may, therefore, be seen as unsuccessful, when there is the possibility that they would do far better in another role that offers trait-relevant situations with greater regularity.

Testing the theory

Since its introduction, several researchers have sought to test this idea. Tett and Guterman (2000) conducted one of the first large-scale tests via an investigation of the impact of situation trait relevance on the relationship between traits and behaviors. Specifically, they analyzed the relationships between participants' responses to a personality test assessing five personality traits (risk taking, complexity, empathy, sociability, and organization) and responses to a measure about behavioral intentions in multiple scenarios designed to target these same traits. Results of these tests support the notion that traits are expressed to the degree that the situation offers opportunities for their expression. In addition, the study found support for the idea that situations can be assessed for the degree to which they are relevant to certain traits (even those targeting the same trait).

Kamdar and Van Dyne (2007)[11] also found support for the theory via a field research study in which they examined 230 employees, their coworkers, and their supervisors and found that high quality social exchange relationships at work weakened the positive relationship between personality (specifically, agreeableness and conscientiousness) and job performance. These results were interpreted to be consistent with trait activation theory because they suggested that high quality social exchange relationships signaled the existence of a norm of reciprocity that subsequently constrained the expression of personality. With respect to agreeableness, for example, the authors hypothesized that, relative to those high in agreeableness, less agreeable employees do not have natural inclinations for tolerance and empathy, and therefore "need other incentives to motivate helping such as the sense that relationship partners are trustworthy"(p. 1290). Similar conclusions were drawn with respect to employees who scored relatively low on conscientiousness.

Most recently, Judge and Zapata (2015)[5] developed and tested an interactionist framework of the personality to job performance relationship, focusing on both general (situation strength;[12]) and specific (trait activation; Tett & Burnett, 2003) situational influences. In doing so, they integrated both perspectives and compared the predictive validity of both perspectives, concluding that trait activation theory may be relatively more important than situation strength theory in explaining when and how personality is more predictive of job performance (p. 1167). However, the authors are careful to note that the variance attributable to situational strength is not inconsequential. These authors also note that the study was limited due to its focus on job and task-based cues (to the explicit neglect of social cues) which could also impact the personality-job performance relationship.

Practical implications

When organizations understand how different organizational cues lead to expression of traits, this knowledge allows organizations the opportunity to create situations that "activate" the traits they most value, and to select employees based on those traits. However, to understand fully the traits needed for different occupational roles, including team contexts, management scholars recommend organizations conduct Personality-Oriented Work Analyses to improve selection and promotion processes.[13] Placing employees in positions that demand their personality traits can benefit the employee as well as the organization. When considering motivation, Trait activation theory often describes trait expression as a form of need satisfaction.[4] In addition to the extrinsic rewards employees receive from positive trait expression, employees gain intrinsic satisfaction from work environments that provide opportunities for trait expression. Essentially according to Trait activation theory, individuals are happier and can perform better in employment environments where they feel rewarded for being themself.[4] Trait activation theory also suggests that workplaces should limit the situational cues and stressors that lead individuals with certain personality traits to counterproductive work behavior[14]

Organizations can use trait activation theory to help them ensure a positive applicant experience. A 2015 study found that for applicants who were significantly strong in the desirable traits for the position they were being considered for, perceived personality fit with current employees played a large role in their perception of the organization.[15] Using trait activation theory and the related similarity-attraction theory, organizations can design their recruitment processes in such a way that applicants connect to current employees with whom they are likely to identify. The study suggests that the more applicants can come in contact with successful and happy employees that they personally relate to, the more confident they are likely to be in their happiness in a similar environment.

Trait activation theory can also help an organization understand how to optimally motivate workers by offering them rewards suited to their individual traits (e.g., introverts will likely not be motivated by rewards involving public recognition such as "employee of the month" but extraverts will be[2]). In the workplace discussion, trait activation theory is often discussed only in relation to task motivation and execution. However, this is an example of its uses beyond that focus. One 2017 study discussed how trait activation theory can help guide an organization's assessment of leadership potential among its employees.[16] It suggests situations more likely to activate certain key traits associated with leadership ability.

Trait activation theory is used in many areas of psychological study and practice, especially in industrial/organizational psychology. One area that it has strongly affected is assessment centers.[17] With conclusions drawn from trait activation theory, assessment centers can write more reliable assessments and interpret results with greater accuracy to suggest whether a tester is more or less likely to thrive in a certain area.

Role in explaining situational specificity

Although not an explicit test of the theory's principles per se, scholars have frequently drawn from trait activation theory to account for inconsistencies in the relationship between personality and work behavior such as performance.[18][19] Trait activation theory considers the interaction between traits and situations, where the same situation can have different effects on individuals with different trait levels, situational specificity considers the differences in the behavior of the same person in different situations. Situation trait relevance is often considered which means that a situation is effected by a personality trait at different levels depending on the frequency of opportunities for that trait to be expressed.[4] For example, personality traits like agreeableness may be key for performance in jobs that require helping others, but less predictive of performance in jobs that do not require the provision of help to others. Likewise, the theory has been used to explain why relatively extraverted individuals seem to perform better in occupations (i.e., those of managers and sales) that involve high levels of social interaction.[20]: 1–26

Criticism

The theory does not appear to address how trait-relevant behavioral tendencies are converted into work behaviors. Some scholars have attempted to address this gap by suggesting higher-order goals, such as the motivation to experience meaningfulness at work, play a role in how trait relevant tendencies are translated into relevant work outcomes (see[20]: 132–153 ).

Other relevant concepts

Bidirectionality – a personality trait can positively predict job performance in one situation and negatively predict job performance in another situation. For example, conscientious individuals tend to be detail-oriented and cautious in their decision making; generally speaking, conscientiousness is associated with positive job performance behaviors. In contrast, research has shown that organizations selecting for job positions that requires an employee be adaptable to change might not benefit from selecting an individual high in conscientiousness.[21]

Situational strength is also relevant from the trait activation perspective and refers to cues provided regarding desirability of behavior.[12] So-called "strong" situations involve unambiguous demands (the classic example is a red traffic light), whereas "weak" situations are characterized by more ambiguous expectations for behavior.[22] Situation strength is related to trait relevance insofar as trait relevance is essentially a characteristic of a situation that can lead to the expression of one trait rather than another. To expound upon this relationships, Tett and Burnett (2003)[1] use the metaphor of a radio station and its corresponding volume in order to distinguish between trait relevance and situation strength, respectively. Specifically, they suggest that trait relevance is analogous to the radio station (i.e., channel) and situation strength to the volume at which the station is played. In other words, trait relevance determines if a situation offers the opportunity (based on task, social, and/or organizational cues) to express a certain trait, and the strength of the situation determines the likelihood that individuals will express the relevant trait or not.

For example, a strong situation might include an interdisciplinary work team where there is a common organizational expectation that all team members will help each other, as each member depends on other team member's expertise and experience. In this situation, the agreeableness trait might be activated by the tasks and the organization cues, but even individuals lower on agreeableness will likely help others. In contrast, a weak situation could involve a new employee joining a workgroup where no expectations regarding how people work together have been set. This employee may realize that he has a unique experience that if shared would help another team member finish his task more quickly. In this situation, the agreeableness trait might be activated by knowledge he can help a coworker with a task, but generally without other cues present, it is more likely that those high in agreeableness will offer to help.

Trait theory is a psychological approach that includes studying personality traits as relatively stable individual differences which describe general predispositions or predictable common patterns of thinking and experiencing emotions that influence behavior.[23] In fact, personality traits have been associated with important life outcomes (see Personality and life outcomes). The most well-known description or categorization of personality traits is called the "Big Five personality traits" which includes five broad personality dimensions: conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, openness, and neuroticism (or, in its inverse form, emotional stability[24]).

In personality psychology there has been a long-standing person-situation debate wherein trait theorists suggested behavior could be predicted by analyzing consistent personalities across situations, but "situationists" disagreed that personalities were as consistent as trait theorists suggested. Situationists argued that the external situation – not general traits – was what influenced behavior. Today, most personality psychologists adhere to an interactionist perspective, where both person and situation contribute to human behavior; as a result, the primary debate no longer exists.[25]

Personality-job fit theory (based on the broader concept of person-environment fit) suggests that certain job environments are more suited to individuals with certain personality characteristics, and that hiring individuals who are the best "fit" will result in higher employee satisfaction, well-being and better job performance. In other words, personality-job fit theory is based on an interactional model which suggests that both person and situation interact to influence behavior.[26]

See also

- Social:Job performance – Assesses whether a person performs a job well

- Social:Personality–job fit theory – Psychology that postulates person's personality traits will reveal insight to adaptability

- Social:Situationism (psychology) – Theory

- Social:Trait theory – Approach to the study of human personality

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Tett, R. P.; Burnett, D. D. (2003). "A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance". Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (3): 500–517. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500. PMID 12814298.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Simonet, Daviel V.; Tett, R.P. (2013). "5 perspectives on the leadership-management relationship: a competency-based evaluation and integration". Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 20 (2): 199–213. doi:10.1177/1548051812467205.

- ↑ Tett, Robert P.; Toich, Margaret J.; Ozkum, S. Burak (2021-01-21). "Trait Activation Theory: A Review of the Literature and Applications to Five Lines of Personality Dynamics Research" (in en). Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 8 (1): 199–233. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-062228. ISSN 2327-0608. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-062228.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Tett, Robert P.; Toich, Margaret J.; Ozkum, S. Burak (2021-01-21). "Trait Activation Theory: A Review of the Literature and Applications to Five Lines of Personality Dynamics Research" (in en). Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 8 (1): 199–233. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-062228. ISSN 2327-0608. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-062228.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Judge, T.; Zapata, C. (2015). "The person-situation debate revisited: Effect of situation strength and trait activation on the validity of the big five personality traits in predicting job performance". Academy of Management Journal 58 (4): 1149–1179. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0837.

- ↑ Eysenck, H. J.; Eysenck, M. W. (1985). Personality and individual differences: a natural science approach. New. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- ↑ Tett, Robert P.; Guterman, Hal A. (2000-12-01). "Situation Trait Relevance, Trait Expression, and Cross-Situational Consistency: Testing a Principle of Trait Activation" (in en). Journal of Research in Personality 34 (4): 397–423. doi:10.1006/jrpe.2000.2292. ISSN 0092-6566. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S009265660092292X.

- ↑ Hatipoglu, Sercan; Koc, Erdogan (January 1, 2023). "The Influence of Introversion–Extroversion on Service Quality Dimensions: A Trait Activation Theory Study" (in en). Sustainability 15 (1): 798. doi:10.3390/su15010798. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ↑ Kenrick, D. T.; Funder, D. C. (1988). "Profiting from controversy: Lessons from the person-situation debate". American Psychologist 43 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.43.1.23. PMID 3279875.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Tett, R. P.; Guterman, H. A. (2000). "Situation trait relevance, trait expression, and cross-situational consistency: Testing a principle of trait activation". Journal of Research in Personality 34 (4): 397–423. doi:10.1006/jrpe.2000.2292.

- ↑ Kamdar, D.; Van Dyne, L. (2007). "The joint effects of personality and workplace social exchange relationships in predicting task performance and citizenship performance.". Journal of Applied Psychology 92 (5): 1286–1298. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1286. PMID 17845086.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Meyer, R. D.; Dalal, R. S.; Hermida, R. (2010). "A review and synthesis of situational strength in the organizational sciences". Journal of Management 36: 121–140. doi:10.1177/0149206309349309.

- ↑ Kell, H. J.; Rittmayer, A. D.; Crook, A. E.; Motowidlo, S. J. (2010). "Situational content moderates the association between the Big Five personality traits and behavioral effectiveness". Human Performance 23 (3): 213–228. doi:10.1080/08959285.2010.488458.

- ↑ O'Brien, Kimberly E.; Henson, Jeremy A.; Voss, Bernard E. (2021). "A trait-interactionist approach to understanding the role of stressors in the personality–CWB relationship." (in en). Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 26 (4): 350–360. doi:10.1037/ocp0000274. ISSN 1939-1307. PMID 33734739. http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/ocp0000274.

- ↑ Van Hoye, Greet; Turban, Daniel B. (2015). "Applicant-employee fit in personality: Testing predictions from similarity-attraction theory and trait activation theory". International Journal of Selection and Assessment 23 (3): 210–223. doi:10.1111/ijsa.12109.

- ↑ Luria, Gil; Kahana, Allon; Goldenberg, Judith; Noam, Yair (2017). "Contextual moderators for leadership potential based on trait activation theory". Journal of Organizational Behavior 40 (8): 899–911. doi:10.1002/job.2373.

- ↑ Haaland, Stephanie; Christiansen, Neil D. (2006). "Implications of Trait-Activation Theory for Evaluating the Construct Validity of Assessment Center Ratings". Personnel Psychology 55 (1): 137–163. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2002.tb00106.x.

- ↑ Chen, G.; Kirkman, B. L.; Kim, K.; Farh, C.I.; Tangirala, S. (2010). "When does cross-cultural motivation enhance expatriate effectiveness? A multilevel investigation of the moderating roles of subsidiary support and cultural distance.". Academy of Management Journal 53 (5): 1110–1130. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.54533217.

- ↑ Jiang, C.; Wang, D.; Zhou, F. (2009). "Personality traits and job performance in local government organizations in China.". Social Behavior and Personality 37 (4): 451–457. doi:10.2224/sbp.2009.37.4.451.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Barrick, M. R.; Mount, M. K. (1991). "The theory of purposeful work behavior: The role of personality, higher-order goals, and job characteristics". Personnel Psychology 44: 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x.

- ↑ LePine, J. A.; Funder, D. C. (1988). "Adaptability to changing task contexts: Effects of general cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and openness to experience". Personnel Psychology 53 (3): 563–593. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2000.tb00214.x.

- ↑ Mischel, W. (1973). "Toward a cognitive-affective system theory of personality". Psychological Review 80 (4): 252–253. doi:10.1037/h0035002. PMID 4721473. https://polipapers.upv.es/index.php/reinad/article/view/4214.

- ↑ Allport, G. W. (1927). "Concepts of trait and personality". Psychological Bulletin 24 (5): 284–293. doi:10.1037/h0073629.

- ↑ McCrae, R. R.; Costa, P. T. (1997). "Personality trait structure as a human universal". American Psychologist 52 (5): 509–516. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.52.5.509. PMID 9145021. https://zenodo.org/record/1231466.

- ↑ Fleeson, W.; Noftle, E. E. (2009). "In favor of the synthetic resolution to the person–situation debate". Journal of Research in Personality 43 (2): 150–154. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.02.008.

- ↑ Chatman, J. A. (1989). "Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit.". Academy of Management Review 14 (3): 333–349. doi:10.5465/amr.1989.4279063.

|