Social:Unemployment benefits

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

Unemployment benefits (depending on the jurisdiction also called unemployment insurance or unemployment compensation) are payments made by back authorized bodies to unemployed people. In the United States, benefits are funded by a compulsory governmental insurance system, not taxes on individual citizens. Depending on the jurisdiction and the status of the person, those sums may be small, covering only basic needs, or may compensate the lost time proportionally to the previous earned salary.

Unemployment benefits are generally given only to those registering as unemployed, and often on conditions ensuring that they seek work and do not currently have a job, and are validated as being laid off and not fired for cause in most states.

History

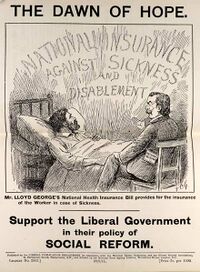

The first unemployment benefit scheme was introduced in the United Kingdom with the National Insurance Act 1911 under the Liberal Party government of H. H. Asquith. The popular measures were to combat the increasing influence of the Labour Party among the country's working-class population. The Act gave the British working classes a contributory system of insurance against illness and unemployment. It only applied to wage earners, however, and their families and the unwaged had to rely on other sources of support, if any.[1] Key figures in the implementation of the Act included Robert Laurie Morant, and William Braithwaite.

By the time of its implementation, the benefit was criticized by communists, who thought such insurance would prevent workers from starting a revolution, while employers and tories saw it as a "necessary evil".[2]

The scheme was based on actuarial principles and it was funded by a fixed amount each from workers, employers, and taxpayers. It was restricted to particular industries, particularly more volatile ones like shipbuilding, and did not make provision for any dependants. After one week of unemployment, the worker was eligible for receiving 7 shillings/week for up to 15 weeks in a year. By 1913, 2.3 million were insured under the scheme for unemployment benefit.

Expansion and spread

The Unemployment Insurance Act 1920 created the dole system of payments for unemployed workers.[3] The dole system provided 39 weeks of unemployment benefits to over 11 million workers—practically the entire civilian working population except domestic service, farm workers, railroad men, and civil servants.

Unemployment benefits were introduced in Germany in 1927, and in most European countries in the period after the Second World War with the expansion of the welfare state. Unemployment insurance in the United States originated in Wisconsin in 1932.[4] Through the Social Security Act of 1935, the federal government of the United States effectively encouraged the individual states to adopt unemployment insurance plans.

Argentina

In Argentina , successive administrations have used a variety of passive and active labour market interventions to protect workers against the consequences of economic shocks. The government's key institutional response to combat the increase in poverty and unemployment created by the crisis[clarification needed] was the launch of an active unemployment assistance programme called Plan Jefas y Jefes de Hogar Desocupados (Program for Unemployed Heads of Households).

Australia

In Australia , social security benefits, including unemployment benefits, are funded through the taxation system. There is no compulsory national unemployment insurance fund. Rather, benefits are funded in the annual Federal Budget by the National Treasury and are administrated and distributed throughout the nation by the government agency, Centrelink. Benefit rates are indexed to the Consumer Price Index and are adjusted twice a year according to inflation or deflation.

There are two types of payment available to those experiencing unemployment. The first, called Youth Allowance, is paid to young people aged 16–20 (or 15, if deemed to meet the criteria for being considered 'independent' by Centrelink). Youth Allowance is also paid to full-time students aged 16–24, and to full-time Australian Apprenticeship workers aged 16–24. People aged below 18 who have not completed their High School education, are usually required to be in full-time education, undertaking an apprenticeship or doing training to be eligible for Youth Allowance. For single people under 18 years of age living with a parent or parents the basic rate is A$91.60 per week. For over-18- to 20-year-olds living at home this increases to A$110.15 per week. For those aged 18–20 not living at home the rate is A$167.35 per week. There are special rates for those with partners and/or children.

The second kind of payment is called Newstart Allowance and is paid to unemployed people over the age of 21 and under the pension eligibility age. To receive a Newstart payment, recipients must be unemployed, be prepared to enter into an Employment Pathway Plan (previously called an Activity Agreement) by which they agree to undertake certain activities to increase their opportunities for employment, be Australian Residents and satisfy the income test (which limits weekly income to A$32 per week before benefits begin to reduce, until one's income reaches A$397.42 per week at which point no unemployment benefits are paid) and the assets test (an eligible recipient can have assets of up to A$161,500 if he or she owns a home before the allowance begins to reduce and $278,500 if he or she does do not own a home). The rate of Newstart allowance as at 12 January 2010 for single people without children is A$228 per week, paid fortnightly. (This does not include supplemental payments such as Rent Assistance.) Different rates apply to people with partners and/or children.

Effectively, people have had to survive on $39 a day from Newstart since 1994, and there have been calls to raise this by politicians and NGO groups.[5]

The system in Australia is designed to support recipients no matter how long they have been unemployed. In recent years the former Coalition government under John Howard has increased the requirements of the Activity Agreement, providing for controversial schemes such as Work for the Dole, which requires that people on benefits for 6 months or longer work voluntarily for a community organisation regardless of whether such work increases their skills or job prospects. Since the Labor government under Kevin Rudd was elected in 2008, the length of unemployment before one is required to fulfill the requirements of the Activity Agreement (which has been renamed the Employment Pathway Plan) has increased from six to twelve months. There are other options available as alternatives to the Work for the Dole scheme, such as undertaking part-time work or study and training, the basic premise of the Employment Pathway Plan being to keep the welfare recipient active and involved in seeking full-time work.

For people renting their accommodation, unemployment benefits are supplemented by Rent Assistance, which, for single people as at 29 June 2012, begins to be paid when weekly rent is more than A$53.40. Rent Assistance is paid as a proportion of total rent paid (75 cents per dollar paid over $53.40 up to the maximum). The maximum amount of rent assistance payable is A$60.10 per week, and is paid when the total weekly rent exceeds A$133.54 per week. Different rates apply to people with partners and/or children, or who are sharing accommodation.

External links

Canada

In Canada , the system now known as Employment Insurance was formerly called Unemployment Insurance. The name was changed in 1996, in order to alleviate perceived negative connotations. In 2015, Canadian workers pay premiums of 1.88%[6] of insured earnings in return for benefits if they lose their jobs.

The Employment and Social Insurance Act was passed in 1935 during the Great Depression by the government of R.B. Bennett as an attempted Canadian unemployment insurance programme. It was, however, ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of Canada as unemployment was judged to be an insurance matter falling under provincial responsibility. After a constitutional amendment was agreed to by all of the provinces, a reference to "Unemployment Insurance" was added to the matters falling under federal authority under the Constitution Act, 1867, and the first Canadian system was adopted in 1940. Because of these problems Canada was the last major Western country to bring in an employment insurance system. It was extended dramatically by Pierre Trudeau in 1971 making it much easier to get. The system was sometimes called the 10/42, because one had to work for 10 weeks to get benefits for the other 42 weeks of the year. It was also in 1971 that the UI program was first opened up to maternity and sickness benefits, for 15 weeks in each case.

The generosity of the Canadian UI programme was progressively reduced after the adoption of the 1971 UI Act. At the same time, the federal government gradually reduced its financial contribution, eliminating it entirely by 1990. The EI system was again cut by the Progressive Conservatives in 1990 and 1993, then by the Liberals in 1994 and 1996. Amendments made it harder to qualify by increasing the time needed to be worked, although seasonal claimants (who work long hours over short periods) turned out to gain from the replacement, in 1996, of weeks by hours to qualify. The ratio of beneficiaries to unemployed, after having stood at around 40 percent for many years, rose somewhat during the 2009 recession but then fell back again to the low 40s.[7] Some unemployed persons are not covered for benefits (e.g. self-employed workers), while others may have exhausted their benefits, did not work long enough to qualify, or quit or were dismissed from their job. The length of time one could take EI has also been cut repeatedly. The 1994 and 1996 changes contributed to a sharp fall in Liberal support in the Atlantic provinces in the 1997 election.

In 2001, the federal government increased parental leave from 10 to 35 weeks, which was added to preexisting maternity benefits of 15 weeks. In 2004, it allowed workers to take EI for compassionate care leave while caring for a dying relative, although the strict conditions imposed make this a little used benefit. In 2006, the Province of Quebec opted out of the federal EI scheme in respect of maternity, parental and adoption benefits, in order to provide more generous benefits for all workers in that province, including self-employed workers. Total EI spending was $19.677 billion for 2011-2012 (figures in Canadian dollars).[8]

Employers contribute 1.4 times the amount of employee premiums. Since 1990, there is no government contribution to this fund. The amount a person receives and how long they can stay on EI varies with their previous salary, how long they were working, and the unemployment rate in their area. The EI system is managed by Service Canada, a service delivery network reporting to the Minister of Employment and Social Development Canada.

A bit over half of EI benefits are paid in Ontario and the Western provinces but EI is especially important in the Atlantic provinces, which have higher rates of unemployment. Many Atlantic workers are also employed in seasonal work such as fishing, forestry or tourism and go on EI over the winter when there is no work. There are special rules for fishermen making it easier for them to collect EI. EI also pays for maternity and parental leave, compassionate care leave, and illness coverage. The programme also pays for retraining programmes (EI Part II) through labour market agreements with the Canadian provinces.

A significant part of the federal fiscal surplus of the Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin years came from the EI system. Premiums were reduced much less than falling expenditures - producing, from 1994 onwards, EI surpluses of several billion dollars per year, which were added to general government revenue.[9] The cumulative EI surplus stood at $57 billion at 31 March 2008,[10] nearly four times the amount needed to cover the extra costs paid during a recession.[11] This drew criticism from Opposition parties and from business and labour groups, and has remained a recurring issue of the public debate. The Conservative Party,[12] chose not to recognize those EI surpluses after being elected in 2006. Instead, the Conservative government cancelled the EI surpluses entirely in 2010, and required EI contributors to make up the 2009, 2010 and 2011 annual deficits by increasing EI premiums. On 11 December 2008, the Supreme Court of Canada rejected a court challenge launched against the federal government by two Quebec unions, who argued that EI funds had been misappropriated by the government.[13]

External links

- [2] History of UI in Canada, since the 1930s

- [3] Canadian Government Site for EI

- [4] Canadian Government Site for Maternity and Parental Benefits

- [5] Library of Parliament publication on EI premiums

- CBC Digital Archives - On The Dole: Employment Insurance in Canada

China

The level of benefit is set between the minimum wage and the minimum living allowance by individual provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities.[citation needed]

Denmark

European Union

Each Member State of the European Union has its own system and in general a worker should claim unemployment benefits in the country where they last worked. For a person working in a country other than their country of residency (a cross-border worker), they will have to claim benefits in their country of residence.[14]

Finland

Two systems run in parallel, combining a Ghent system and a minimum level of support provided by Kela, an agency of the national government. Unionization rates are high (70%), and union membership comes with membership in an unemployment fund. Additionally, there are non-union unemployment funds. Usually benefits require 26 weeks of 18 hours per week on average, and the unemployment benefit is 60% of the salary and lasts for 500 days.[15] When this is not available, Kela can pay either regular unemployment benefit or labor market subsidy benefits. The former requires a degree and two years of full-time work. The latter requires participation in training, education, or other employment support, which may be mandated on pain of losing the benefit, but may be paid after the regular benefits have been either maxed out or not available.[16] Although the unemployment funds handle the payments, most of the funding is from taxes and compulsory tax-like unemployment insurance charges.

Regardless of whether benefits are paid by Kela or from an unemployment fund, the unemployed person receives assistance from the Työ- ja elinkeinokeskus (TE-keskus, or the "Work and Livelihood Centre"), a government agency which helps people to find jobs and employers to find workers. In order to be considered unemployed, the seeker must register at the TE-keskus as unemployed. If the jobseeker does not have degree, the agency can require the jobseeker to apply to a school.

If the individual does not qualify for any unemployment benefit he may still be eligible for the housing benefit (asumistuki) from Kela and municipal social welfare provisions (toimeentulotuki). They are not unemployment benefits and depend on household income, but they have in practice become the basic income of many long-term unemployed.

France

France uses a quasi Ghent system, under which unemployment benefits are distributed by an independent agency (UNEDIC) in which unions and Employer organisations are equally represented. UNEDIC is responsible for 3 benefits: ARE, ACA and ASR The main ARE scheme requires a minimum of 122 days membership in the preceding 24 months and certain other requirements before any claims can be made. Employers pay a contribution on top of the pre-tax income of their employees, which together with the employee contribution, fund the scheme.

The maximum unemployment benefit is (as of March 2009) 57.4% of EUR 162 per day (Social security contributions ceiling in 2011), or 6900 euros per month.[17] Claimants receive 57,4% of their average daily salary of the last 12 months preceding unemployment with the average amount being 1,111 euros per month.[18] In France tax and other payroll taxes are paid on unemployment benefits. In 2011 claimants received the allowance for an average 291 days.

Germany

Germany has two different types of unemployment benefits.

Unemployment benefit I

The unemployment benefit I in Germany is also known as the unemployment insurance. The insurance is administered by the federal employment agency and funded by employee and employer contributions. This in stark contrast to FUTA in the US and other systems; where only employers make contributions. Participation (and thus contributions) are generally mandatory for both employee and employer.

All workers with a regular employment contract (abhängig Beschäftigte), except freelancers and certain civil servants (Beamte), contribute to the system. Since 2006, certain previously excluded workers have been able to opt into the system on a voluntary basis.

The system is financed by contributions from employees and employers. Employees pay 1.5% of their gross salary below the social security threshold and employers pay 1.5% contribution on top of the salary paid to the employee. The contribution level was reduced from 3.25% for employees and employers as part of labour market reforms known as Hartz. Contributions are paid only on earnings up to the social security ceiling (2012: 5,600 EUR).

The system is largely self-financed but also receives a subsidy from the state to run the Jobcenters.

Unemployed workers are entitled to:

- Living allowance known as unemployment benefit

- Help in finding work

- Training

Unemployed benefit is paid to workers who have contributed at least during 12 months preceding their loss of a job. The allowance is paid for half of the period that the worker has contributed. Claimants get 60% of their previous net salary (capped at the social security ceiling), or 67% for claimants with children. The maximum benefit is therefore 2964 Euros (in 2012). In 2011 the federal Work Agency had revenues and expenses of 37.5 bn EUR[19]

After a change in German law effective since 2008, provided their job history qualifies them, benefit recipients aged 50 to 54 now receive an unemployment benefit for 15 months, those 55 to 57 for 18 months and those 58 or older receive benefits for 24 months. For those under the age of 50 who have not been employed for more than 30 months in a job which paid into the social security scheme, full unemployment benefit can be received for a maximum period of 12 months. Note how the duration of eligibility is variegated in Germany to account for the difficulty older people have re-entering the job market.

Unemployment benefit II

If a worker is not eligible for the full unemployment benefits or after receiving the full unemployment benefit for the maximum of 12 months, he is able to apply for benefits from the so-called Arbeitslosengeld II (Hartz IV) programme, an open-ended welfare programme which ensures people do not fall into penury. A person receiving Hartz IV benefits is paid 404 EUR (2016) a month for living expenses plus the cost of adequate housing (including heating) and health care. Couples can receive benefits for each partner including their children. Additionally, children can get "benefits for education and participation". Germany does not have an EBT (electronic benefits transfer) card system in place and, instead, disburses welfare in cash or via direct deposit onto the recipient's bank account. People who receive Hartz 4 are obligated to seek for jobs and can be forced to take part in social programs or Mini jobs in order to receive this Hartz 4 money. Most of these programs and Mini jobs oblige the employee to work the same hours as a normal full time job each day, 5 days a week.

Greece

Unemployment benefits in Greece are administered through ΟΑΕΔ (Greek: Οργανισμός Απασχόλησης Εργατικού Δυναμικού, Manpower Employment Organization) and are available only to laid-off salaried workers with full employment and social security payments during the previous two years. The self-employed do not qualify, and neither do those with other sources of income. The monthly benefit is fixed at the "55% of 25 minimum daily wages", and is currently 360 euros per month,[20][21] with a 10% increase for each under-age child. Recipients are eligible for at most twelve months; the exact duration depends on the collected number of ensema ένσημα, that is social security payment coupons-stamps collected (i.e. days of work) during the 14 months before being laid off; the minimum number of such coupons, under which there is no eligibility, is 125, collected in the first 12 of the 14 aforementioned months. Eligibility since 1 January 2013, has been further constrained in that one applying for unemployment benefits for a second or more time, must not have received more than the equivalent of 450 days of such benefits during the last four years since the last time one had started receiving such benefits; if one has received unemployment benefits in this period for more than 450 days then there is no eligibility while if one has received less, then one is only eligible for at most the remaining days up until the maximum of 450 days is reached.[21]

In terms of an unemployment allowance, Greece allows for those found in unemployment, who are employed through an independent profession, to receive benefits if their latest paycheck had not exceed a certain amount, the current rate should not exceed € 1,467.35. When receiving benefits an individual cannot be earning money from a self-employed profession. If the income increases the fixed amount, a tax authority must issue a certificate that explains that the individual has "interrupted the exercise of the profession", which must be done within 15 days.[22] Unemployment benefits are also granted to those who have generated an income that does not exceed €1,467.35 from the final paycheck received from a liberal profession. In order to receive a grant the individual must not be receiving an income from the previous liberal profession. Under the European Commission, liberal professions are professions that require specialized training and that are regulated by "national governments or professional bodies".[23] Seasonal aid is also provided to workers whose jobs cannot be performed through the entire year are also provided benefits by the OAED. [24]

Under the OAED, individuals who are benefiting from long-term unemployment must be within the ages of 20 to 66 years of age and have a family income that does not exceed € 10,000 annually.[22] An individual becomes eligible for long-term benefits if the regular unemployment subsidy is exhausted after 12 months. After the expiration of the 12 month period an application towards long-term unemployment benefits must be submitted in the first 2 months. If an unemployed person seeks long term unemployment and has a child, the allowance is allowed to increase by € 586.08 (per child). Long-term unemployment can only be granted if the individual can be found registered under the OAED unemployment registrar.[22]

Iceland

To receive unemployment benefits in Iceland, one must submit an application to the Directorate of Labour (Vinnumálastofnun) and meet a specific criteria set forth by the department.[25] Icelandic employment rates have traditionally been higher than every other OECD country. In the most recent financial quarter, 85.8 percent of the Icelandic working-age population were employed, with only 2.8 percent of the population unemployed.[26] When broken down by age group, Iceland's labor force is highly active, with 74.9 percent of the population between the ages of 15 to 24 years old and 89.4 percent of people between the ages of 25 to 55 years old active in the labor market.[26] This low rate of unemployment is attributed to the adoption of the Ghent system, which has been adopted by the countries of Denmark , Finland and Sweden, and highly emphasizes trade and labor unions to provide unemployment benefits and protections to workers, which ultimately has led to higher union membership than other capitalist economies.[27] The safety net that these unions provide also leads to more stable job retention and less reliance on part-time employment. Only 11.9 percent of the working population is dependent on temporary employment.[26]

Unlike purely social-democratic states in Europe, the Nordic model that Iceland adopted borrows aspects of both a social-democratic and liberal-welfare state.[28] Iceland not only sees high government involvement in providing social welfare and ammenities as with the social-democratic model, but like the liberal-welfare model, it is also heavily reliant on free trade and markets.[28] The country relies on an open capitalistic market for economic growth, yet also embraces a corporatist system that allows for wage bargaining to occur between the labor force and employers in order to protect workers and ensure provisions like unemployment benefits are ensured.[29] Currently, the legislation that ensures these benefits is The Act on Trade Unions and Industrial Disputes, which was adopted in 1938 and has been amended five times since its inception to adjust to the rise of globalization. In Section 1, Articles 1-13 grant trade unions the right to organize and negotiate with employers over fair wages for its members as well as representation for their members in the event of workplace conflicts.[30] These rights for organized unions set forth by the Ministry of Welfare not only provide the country's labor force fair and equal representation within their respective industries, but also allow for these organizations to maintain an active relationship with the Icelandic government to discuss economic issues, promote labor and social equality, and ensure benefits for unemployed laborers, as these unions are highly centralized and not politically affiliated.[30]

Unemployment benefits in Iceland (atvinnuleysisbætur) can involve up to 100 percent reimbursement per month for wage earners for a maximum of 30 months.[31] However, these rates of reimbursement are determined by previous status of employment, such as whether an individual is a wage-earner or is self-employed, as well as meeting certain mandates such as being a current resident of Iceland, be actively searching for employment, and retaining a 25 percent position for three months within the past 12 months before filing for unemployment. [31] Unemployed workers can be compensated through either basic or income-linked benefits. Basic unemployment benefits can cover both wage-earning and self-employing individuals for the first half-month (10 days) after they lose their job, whereas income-linked benefits can cover wage-earning and self-employing individuals for up to three months based on a set salary index and length of employment.[25] However, those who are unemployed must report to the Directorate of Labour once a month to reaffirm their status of unemployment and that they are actively searching for employment or unemployment benefits could be revoked.[32] Under the Icelandic Labour Law, employees must be given a notice period of termination that can range from 12 days to six months and is determined by the length of previous employment under the same employer.[33]

Ireland

People aged 18 and over and who are unemployed in Ireland can apply for either the Jobseeker's Allowance (Liúntas do Lucht Cuardaigh Fostaíochta) or the Jobseeker's Benefit (Sochar do Lucht Cuardaigh Fostaíochta). Both are paid by the Department of Social Protection and are nicknamed "the dole".

Unemployment benefit in Ireland can be claimed indefinitely for as long as the individual remains unemployed. The standard payment is €193 per week for those aged 26 and over. For those aged 18 to 24 the rate is €100 per week. For those aged 25 the weekly rate is €144. Payments can be increased if the unemployed has dependents. For each adult dependent, another €124.80 is added, €100 if the recipient (as opposed to the dependent) is aged 18 to 24, and for each child dependent €29.80 is added.

There are more benefits available to unemployed people, usually on a special or specific basis. Benefits include the Rent Supplement, the Mortgage Interest Supplement and the Fuel Allowance, among others. People on a low income (which includes those on JA/JB) are entitled to a Medical Card (although this must be applied for separately from the Health Service Executive) which provides free health care, optical care, limited dental care, aural care and subsidised prescription drugs carrying a €2.50 per item charge to a maximum monthly contribution of €25 per household (as opposed to subsidised services like non medical-card holders).

To qualify for Jobseekers Allowance, claimants must satisfy the "Habitual Residence Condition": they must have been legally in the state (or the Common Travel Area) for two years or have another good reason (such as lived abroad and are returning to Ireland after become unemployed or deported). This condition does not apply to Jobseekers Benefit (which is based on Social Insurance payments).

More information on each benefit can be found here:

Israel

In Israel, unemployment benefits are paid by Bituah Leumi (the National Insurance Institute), to which workers must pay contributions. Eligible workers must immediately register with the Employment Service Bureau upon losing their jobs or jeopordize their eligibility, and the unemployment period is considered to start upon registration with the Employment Service Bureau. To be eligible for unemployment benefits, an employee must have completed a "qualifying period" of work for which unemployment insurance contributions were paid, which varies between 300 and 360 days. Employees who were involuntarily terminated from their jobs or who terminated their own employment and can provide evidence of having done so for a justified reason are eligible for immediately receiving unemployment benefits, while those who are deemed to have terminated their employment of their own volition with no justified reason will only begin receiving unemployment benefits 90 days from the start of their unemployment period.[34][35][36]

Unemployment benefits are paid daily, with the amount calculated based on the employee's previous income over the past six months, but not exceeding the daily average wage for the first 125 days of payment and two-thirds of the daily average wage from the 126th day onwards. During the unemployment period, the Employment Service Bureau assists in helping locate suitable work and job training, and regularly reporting to the Employment Service Bureau is a condition for continuing to receive unemployment benefits. A person who was offered suitable work or training by the Employment Service Bureau but refused will only receive unemployment benefits 90 days after the date of the refusal, and 30 days' worth of unemployment benefits will be deducted for each subsequent refusal.[34][35][36]

Members of kibbutzim and moshavim are typically not covered by the national unemployment system and are covered by the community's own social welfare system, unless they are employed outside of their community or directly by the community.

Italy

Unemployment benefits in Italy consists mainly in cash transfers based on contributions (Assicurazione Sociale per l'Impiego, ASPI), up to the 75 percent of the previous wages for up to sixteen months. Other measures are:

- Redundancy Fund (Cassa integrazione guadagni, or CIG): cash benefits provided as shock absorbers to those workers who are suspended or who work only for reduced time due to temporary difficulties of their factories, aiming to help the factories in financial difficulties, by relieving them from the costs of unused workforce

- Solidarity Contracts (Contratti di solidarietà): in the same cases granting CIG benefits, companies can sign contracts with reduced work time, to avoid dismissing redundancy workers. The state will grant to those workers the 60 percent of the lost part of the wage.

- Mobility allowances (Indennità di mobilità),: if the Redundancy Fund does not allow the company to re-establish a good financial situation, the workers can be entitled to mobility allowances. Other companies are provided incentives for employing them. This measure has been abolished in 2012 and will stop working in 2017.

In the Italian unemployment insurance system all the measures are income-related, and they have an average decommodification level. The basis for entitlement is always employment, with more specific conditions for each case, and the provider is quite always the state. An interesting feature worthy to be discussed is that the Italian system takes in consideration also the economic situation of the employers, and aims as well at relieving them from the costs of crisis.

Japan

Unemployment benefits in Japan are called "unemployment insurance" and are closer to the US or Canadian "user pays" system than the taxpayer funded systems in place in countries such as Britain, New Zealand, or Australia. It is paid for by contributions by both the employer and employee.[37]

On leaving a job, employees are supposed to be given a "Rishoku-hyo" document showing their ID number (the same number is supposed to be used by later employers), employment periods, and pay (which contributions are linked to). The reason for leaving is also documented separately. These items affect eligibility, timing, and amount of benefits.[38] The length of time that unemployed workers can receive benefits depends on the age of the employee, and how long they have been employed and paying in.[39]

It is supposed to be compulsory for most full-time employees.[40] If they have been enrolled for at least 6 months and are fired or made redundant, leave the company at the end of their contract, or their contract is non-renewed, the now-unemployed worker will receive unemployment insurance. If a worker quit of their own accord they may have to wait between 1 and 3 months before receiving any payment.

Mexico

Mexico lacks a national unemployment insurance system, but it does have five programs to assist the unemployed:

- Mexico City Unemployment Benefit Scheme - The only unemployment insurance system based on worker contributions exists in Mexico City. Unemployed residents of Mexico City who are at least 18 years of age, have worked for at least six months, have no income, and are actively seeking work are eligible for unemployment benefits for up to six months, which are composed of payments of 30 days' worth of minimum wage per month.[41]

- Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) - This institution insures workers in the formal sector, providing pensions and health insurance. Workers insured by the IMSS who are unemployed may withdraw a maximum of 30 days' worth of pension savings every five years.[41] However, this does not cover the majority of workers, as 58% of the labor force is in the informal sector.

- National Employment Service - This agency, which has 165 offices nationwide, offers financial support in learning new skills to those aged 16 and above who are unemployed or underemployed, and assistance in finding new jobs in the form of information on vacancies and job fairs.[41]

- Temporary Employment Program - This scheme is designed to aid unemployed people who live in rural areas with high unemployment rates, any area undergoing a financial crisis, or an area that has been hit by a natural disaster or some other kind of emergency. The program funds projects to boost employment by hiring local workers aged 16 and above in jobs such as building infrastructure and promoting development, and conserving the environment and cultural heritage sites. They are paid a salary at 99% of the local minimum wage for a maximum of 132 days a year.[41]

- Income Generating Options Program - People living in poverty in an area of up to a maximum of 15,000 inhabitants are eligible for funding for projects to generate income for themselves.[41]

Netherlands

Unemployment benefits in the Netherlands were introduced in 1949. Separate schemes exist for mainland Netherlands and for the Caribbean Netherlands.

The scheme in mainland Netherlands entails that, according to the Werkloosheidswet (Unemployment Law, WW), employers are responsible for paying the contributions to the scheme, which are deducted from the salary received by the employees. In 2012 the contribution was 4.55% of gross salary up to a ceiling of 4,172 euros per month. The first 1,435.75 euros of an employees gross salaries are not subject to the 4.55% contribution.

Benefits are paid for a maximum period of 38 months and claimants get 75% of last salary for 2 months and 70% thereafter with a maximum benefit of 3128 euros, depending on how long the claimant has been employed previously. Workers older than 50 years who are unemployed for over 2 months are entitled to a special benefit called the IOAW, if they do not receive the regular unemployment benefit (WW).

New Zealand

In New Zealand, Jobseeker Support, previously known as the Unemployment Benefit and also known as "the dole" provides income support for people who are looking for work or training for work. It is one of a number of benefits administered by Work and Income, a service of the Ministry of Social Development.

To get this benefit, a person must meet the conditions and obligations specified in section 88A to 123D Social Security Act 1964. These conditions and obligations cover things such as age, residency status, and availability to work.[42]

The amount that is paid depends on things such as the person's age, income, marital status and whether they have children. It is adjusted annually on 1 April and in response to changes in legislature. Some examples of the maximum after tax weekly rate at 1 April 2011 are:

- $175.10 for a single person aged 20–24 years without children

- $210.13 for a single person 25 years or over

- $325.98 for a sole parent

- $350.20 for a married, de facto or civil union couple with or without children ($167.83 each).[43]

More information about this benefit and the amounts paid are on the Work and Income website.[44]

External links

Spain

The Spanish unemployment benefits system is part of the Social security system of Spain. Benefits are managed by the State Public Employment Agency (SEPE).The basis for entitlement is having contributed for a minimum period during the time preceding unemployment, with further conditions that may be applicable. The system comprises contributory benefits and non-contributory benefits.

Contributory benefits are payable to those unemployed persons with a minimum of 12 months contributions over a period of 6 years preceding unemployment. The benefit is payable for 1/3 of the contribution period. The benefit amount is 70% of the legal reference salary plus additional amounts for persons with dependants. The benefit reduces to 60% of the reference salary after 6 months. The minimum benefit is 497 euros per month and the maximum is 1087,20 euros per month for a single person.[45] The non-contributory allowance is available to those persons who are no longer entitled to the contributory pension and who do not have income above 75% of the national minimum wage.

Sweden

Sweden uses the Ghent system, under which a significant proportion of unemployment benefits are distributed by union unemployment funds. Unemployment benefits are divided into a voluntary scheme with income related compensation up to a certain level and a comprehensive scheme that provides a lower level of basic support. The voluntary scheme requires a minimum of 12 months membership and 6 months employment during that time before any claims can be made. Employers pay a fee on top of the pre-tax income of their employees, which together with membership fees, fund the scheme (see Unemployment funds in Sweden).

The maximum unemployment benefit is (as of July 2016) SEK 980 per day. During the first 200 days the unemployed will receive 80 percent of his or her normal income during the last 12 months. From day 201-300 this goes down to 70 percent and from day 301-450 the insurance covers 65 percent of the normal income (only available for parents to children under the age of 18). In Sweden tax is paid on unemployment benefits, so the unemployed will get a maximum of about SEK 10,000 per month during the first 100 days (depending on the municipality tax rate). In other currencies, as of June 2017, this means a maximum of approximately £900, $1,150, or €1,000, each month after tax. Private insurance is also available, mainly through professional organisations, to provide income related compensation that otherwise exceeds the ceiling of the scheme. The comprehensive scheme is funded by tax.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is an economic welfare state with free medical care[46] and unemployment benefits.[47] However, the country relies not on taxation but mainly oil revenues to maintain the social and economic services to its populace.

Payment: 2000 SAR (USD $534) for only 12 months for unemployed person from ages 18–35

External links

United Kingdom

Jobseeker's Allowance rates

JSA for a single person is changed annually, and at 3 August 2012 the maximum payable was £71.00 per week for a person aged over 25 and £56.25 per week for a person aged 18–24.[48] The rules for couples where both are unemployed are more complex, but a maximum of £112.55 per week is payable, dependent on age and other factors. Income-based JSA is reduced for people with savings of over £6,000, by a reduction of £1 per week per £250 of savings, up to £16,000. People with savings of over £16,000 are not able to get IB-JSA at all.[49] The British system provides rent payments as part of a separate scheme called Housing Benefit.

Unemployment benefit is commonly referred to as "the dole"; to receive the benefit is to be "on the dole". "Dole" here is an archaic expression meaning "one's allotted portion", from the synonymous Old English word dāl. [50]

United States

In the United States, there are 50 state unemployment insurance programs plus one each in the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and United States Virgin Islands. Though policies vary by state, unemployment benefits generally pay eligible workers as high as $783.00 per week in the Massachusetts to a low as $235 per week maximum in Mississippi.[51] Benefits are generally paid by state governments, funded in large part by state and federal payroll taxes levied against employers, to workers who have become unemployed through no fault of their own. Eligibility requirements for unemployment insurance vary by state, but generally speaking, employees not fired for misconduct ("terminated for cause") are eligible for unemployment benefits, while those fired for misconduct (this sometimes can include misconduct committed outside the workplace, such as a problematic social media post or committing a crime) are not.[52]

In every state, employees who quit their job without "good cause" are not eligible for unemployment benefits, but the definition of good cause varies by state. In some states, being fired for misconduct permanently bars the employee from receiving unemployment benefits, while in others it only disqualifies the employee for a short period. This compensation is classified as a type of social welfare benefit. According to the Internal Revenue Code, these types of benefits are to be included in a taxpayer's gross income.[53]

The standard time-length of unemployment compensation is six months, although extensions are possible during economic downturns. During the Great Recession, unemployment benefits were extended to 73 weeks.[54]

The Supreme Court held that federal unemployment law is constitutional and does not violate the Tenth Amendment in Steward Machine Company v. Davis, 301 U.S. 548 (1937).

Federal-state joint programs

Unemployment insurance is a federal-state program financed through federal and state payroll taxes (federal and state UI taxes).[55] In most states employers pay state and federal unemployment taxes if:

- (1) they pay wages to employees totaling $1,500 or more in any quarter of a calendar year; or,[55]

- (2) they had at least one employee during any day of a week during 20 weeks in a calendar year, regardless of whether the weeks were consecutive. Some state laws differ from the federal law.[55]

To facilitate this program, the U.S. Congress passed the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA), which authorizes the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to collect an annual federal employer tax used to fund state workforce agencies. FUTA covers the costs of administering the Unemployment Insurance and Job Service programs in all states. In addition, FUTA pays one-half of the cost of extended unemployment benefits which are triggered in periods of high state unemployment. FUTA also provides a fund from which states UI funds may borrow to pay benefits. As originally established, the states paid the federal government.[55]

The FUTA tax rate was originally three percent of taxable wages collected from employers who employed at least four employees,[56] and employers could deduct up to 90 percent of the amount due if they paid taxes to a state to support a system of unemployment insurance which met Federal standards,[4] but the rules have recently changed. The FUTA tax rate is now, as of 30 June 2011, 6.0 percent of taxable wages of employees who meet both the above and following criteria,[55] and the taxable wage base is the first $7,000 paid in wages to each employee during a calendar year.[55] Employers who pay the state unemployment tax on time receive an offset credit of up to 5.4 percent regardless of the rate of tax they pay their state. Therefore, the net FUTA tax rate is generally 0.6 percent (6.0 percent - 5.4 percent), for a maximum FUTA tax of $42.00 per employee, per year (.006 X $7,000 = $42.00). State law determines individual state unemployment insurance tax rates.[55] In the United States, unemployment insurance tax rates use experience rating.[57]

Although the taxable wage base for each state/territory is at least $7,000 as mandated by FUTA, only four states or territories still remain at this minimum.[58] These states/territories include Arizona, California, Florida, and Puerto Rico. Florida and Puerto Rico maintain tax rates similar to those of other states, but Arizona and California both have a higher maximum tax rate. Florida's minimum tax rate is 0.1% and the state maximum is 5.4%[59] and in Puerto Rico, employers are taxed between 2.4% and 5.4% depending on their experience rating.[60] As of 2015, Arizona's minimum was 0.03%, but its maximum was 7.79%.[61] California's tax rate on the taxable wage base is currently higher than the federal minimum of 6.0%. Employers are currently on a tax schedule that requires them to pay a minimum of 1.5% and a maximum 6.2% of the taxable wage base.[62] Even with the federal tax credit of 5.4%, Arizona employers could end up paying $175 per employee ((.0779-.054) x $7,000) and California employers could pay $56 per employee ((.062-.054) x $7,000) versus the FUTA maximum of $42.

Within the above constraints, the individual states and territories raise their own contributions and run their own programs. The federal government sets broad guidelines for coverage and eligibility, but states vary in how they determine benefits and eligibility.

Federal rules are drawn by the United States Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration. For most states, the maximum period for receiving benefits is 26 weeks. There is an extended benefit program (authorized through the Social Security Acts) that may be triggered by the state unemployment rate. Congress has often passed temporary programs to extend benefits during recessions. This was done with the Temporary Extended Unemployment Compensation (TEUC) program in 2002-2003, which has since expired,[63] and remained in force through 2 June 2010, with the Extended Unemployment Compensation 2008 legislation.[64] In July 2010, legislation that provides an extension of federal extended unemployment benefits through November 2010 was signed by the president. The legislation extended benefits for 2.3 million unemployed workers who had exhausted their unemployment benefits.

The federal government lends money to the states for unemployment insurance when states run short of funds which happens when the state's UI fund cannot cover the cost of current benefits. A high unemployment rate shrinks UI tax revenues and increases expenditures on benefits. State UI finances and the need for loans are exacerbated when a state cuts taxes and increases benefits. FUTA loans to state funds are repaid with interest.

Congressional actions to increase penalties for states incurring large debts for unemployment benefits led to state fiscal crises in the 1980s.[citation needed]

One interesting feature of the UI tax is that it targets firms that have recently had layoffs, potentially hitting distressed firms. Recent work shows that UI tax increases significantly reduce hiring and employment in affected firms, potentially eroding the macroeconomics stabilizing influence of the UI program. [65]

Macroeconomic function

To Keynesians, unemployment insurance acts as an automatic stabilizer.[66] Benefits automatically increase when unemployment is high and fall when unemployment is low, smoothing the business cycle; however, others claim that the taxation necessary to support this system serves to decrease employment.[citation needed]

Eligibility and amount

In order to receive benefits, a person must have worked for at least one quarter in the previous year and have been laid-off by an employer. Workers who were temporary or were paid under the table are not eligible for unemployment insurance. If a worker quits without good cause or is fired for misconduct, then they are normally not eligible for UI benefits. There are five common reasons a claim for unemployment benefits are denied: the worker is unavailable for work, the worker quit his or her job without good cause, the worker was fired for misconduct, refusing suitable work, and unemployment resulting from a labor dispute.[67][68] In practice, it is only practical to verify whether the worker quit or was fired. If the worker's claim is denied, then they have the right to appeal. If the worker was fired for misconduct, then the employer has the burden to prove that the termination of employment is a misconduct defined by individual states laws.[69] However, if the employee quit their job, then they must prove that their voluntary separation must be good cause.

Generally, the worker must be unemployed through no fault of his/her own although workers often file for benefits they are not entitled to; when the employer demonstrates that the unemployed person quit or was fired for cause the worker is required to pay back the benefits they received. The unemployed person must also meet state requirements for wages earned or time worked during an established period of time (referred to as a “base period”) to be eligible for benefits. In most states, the base period is usually the first four out of the last five completed calendar quarters prior to the time that the claim is filed.[70] Unemployment benefits are based on reported covered quarterly earnings. The amount of earnings and the number of quarters worked are used to determine the length and value of the unemployment benefit. The average weekly in 2010 payment was $293.[71]

As a result of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act passed in February 2009, many unemployed people receive up to 99 weeks of unemployment benefits; this may depend on State legislation. Before the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the maximum number of weeks allowed was 26.

Application process

It generally takes two weeks for benefit payments to begin, the first being a "waiting week", which is not reimbursed, and the second being the time lag between eligibility for the program and the first benefit actually being paid.

To begin a claim, the unemployed worker must apply for benefits through a state unemployment agency.[70] In certain instances, the employer initiates the process. Generally, the certification includes the affected person affirming that they are "able and available for work", the amount of any part-time earnings they may have had, and whether they are actively seeking work. These certifications are usually accomplished either over the Internet or via an interactive voice response telephone call, but in a few states may be by mail. After receiving an application, the state will notify the individual if they qualify and the rate they will receive every week. The state will also review the reason for separation from employment. Many states require the individual to periodically certify that the conditions of the benefits are still met.

Disqualification/Appeals

If a worker's reason for separation from their last job is due to some reason other than a "lack of work," a determination will be made about whether they are eligible for benefits. Generally, all determinations of eligibility for benefits are made by the appropriate State under its law or applicable federal laws. If a worker is disqualified or denied benefits, they have the right to file an appeal within an established time-frame. The State will advise a worker of his or her appeal rights. An employer may also appeal a determination if they do not agree with the State's determination regarding the employee's eligibility.[70] If the worker's claim is denied, then they have the right to appeal. If the worker was fired for misconduct, then the employer has the burden to prove substantially that the termination of employment is a misconduct defined by individual states laws.[69] However, if the employee quit their job, then they must prove that their voluntary separation must be good cause. Success rate of unemployment appeals is two-thirds, or 67% of the time for the most claimants.[72][73] In the State of Oklahoma, claimants generally win 51.5% of the time in misconduct cases.[74]

Measurement

Current data

Each Thursday, the Department of Labor issues the Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims Report.[75] Its headline number is the seasonally adjusted estimate for the initial claims for unemployment for the previous week in the United States. This statistic, because it is published weekly, is depended on as a current indicator of the labor market and the economy generally.

In 2016, the number of people on unemployment benefits fell to around 1.74 the lowest in the last 4 decades. [76]

Unemployment insurance outlook

Twice a year, the Office of Management and Budget delivers an economic assessment of the unemployment insurance program as it relates to budgetary issues.[77] As it relates to the FY 2012 budget, the OMB reports that the insured unemployment rate (IUR) is projected to average 3.6% in both FY 2011 and in FY 2012. State unemployment regular benefit outlays are estimated at $61 billion in FY 2011 and $64.3 billion in FY 2012, down somewhat from Midsession estimates.[77] Outlays from state trust fund accounts are projected to exceed revenues and interest income by $16.0 billion in FY 2011 and $15.1 billion in FY 2012.[77] State trust fund account balances, net of loans, are projected to continue to fall, from -$27.4 billion at the end of FY 2010 to -$62.7 billion at the end of FY 2013, before starting to grow again.[77]

Net balances are not projected to become positive again until well beyond FY 2016. Up to 40 states are projected to continue borrowing heavily from the Federal Unemployment Account (FUA) over the next few years.[77] The aggregate loan balance is projected to increase from $40.2 billion at the end of FY 2010 to a peak end-of-year balance of $68.3 billion in FY 2013. Due to the high volume of state loans and increased EB payments, FUA and EUCA are projected to borrow $26.7 billion from the general fund in FY 2011 and an additional $19.4 billion in FY 2012, with neither account projected to return to a net positive balance before 2016.[77] The general fund advances must be repaid with interest.[77]

Economic rationale and issues

The economic argument for unemployment insurance comes from the principle of adverse selection. One common criticism of unemployment insurance is that it induces moral hazard, the fact that unemployment insurance lowers on-the-job effort and reduces job-search effort.

Adverse selection

Adverse selection refers to the fact that “workers who have the highest probability of becoming unemployed have the highest demand for unemployment insurance.”[78] Adverse selection causes profit maximizing private insurance agencies to set high premiums for the insurance because there is a high likelihood they will have to make payments to the policyholder. High premiums work to exclude many individuals who otherwise might purchase the insurance. “A compulsory government program avoids the adverse selection problem. Hence, government provision of UI has the potential to increase efficiency. However, government provision does not eliminate moral hazard.”[78]

Moral hazard

“At the same time, those workers who managed to obtain insurance might experience more unemployment otherwise would have been the case.”[78] The private insurance company would have to determine whether the employee is unemployed through no fault of their own, which is difficult to determine. Incorrect determinations could result in the payout of significant amounts for fraudulent claims or alternately failure to pay legitimate claims. This leads to the rationale that if government could solve either problem that government intervention would increase efficiency.

Unemployment insurance effect on unemployment

In the Great Recession, the “moral hazard” issue of whether unemployment insurance—and specifically extending benefits past the maximum 99 weeks—significantly encourages unemployment by discouraging workers from finding and taking jobs was expressed by Republican legislators. Conservative economist Robert Barro found that benefits raised the unemployment rate 2%.[79][80] Disagreeing with Barro's study were Berkeley economist Jesse Rothstein, who found the “vast majority” of unemployment was due to “demand shocks” not “[unemployment insurance]-induced supply reductions.”[80][81] A study by Rothstein of extensions of unemployment insurance to 99 weeks during the Great Recession to test the hypothesis that unemployment insurance discourages people from seeking jobs found the overall effect of UI on unemployment was to raise it by no more than one-tenth of one percent.[82][83]

A November 2011 report by the Congressional Budget Office found that even if unemployment benefits convince some unemployed to ignore job openings, these openings were quickly filled by new entrants into the labor market.[80][84] A survey of studies on unemployment insurance's effect on employment by the Political Economy Research Institute found that unemployed who collected benefits did not find themselves out of work longer than those who didn’t have unemployment benefits; and that unemployed workers did not search for work more or reduce their wage expectations once their benefits ran out.[80][85]

One concern over unemployment insurance increasing unemployment is based on experience rating benefit uses which can sometimes be imperfect. That is, the cost to the employer in increased taxes is less than the benefits that would be paid to the employee upon layoff. The firm in this instance believes that it is more cost effective to lay off the employee, causing more unemployment than under perfect experience rating.[78]

Unemployment insurance effect on employment

An alternative rationale for unemployment insurance is that it may allow for improving the quality of matches between workers and firms. Marimon and Zilibotti argued that although a more generous unemployment benefit system may indeed increase the unemployment rate, it may also help improve the average match quality.[86] A similar point is made by Mazur who analyzed the welfare and inequality effects of a policy reform giving entitlement for unemployment insurance to quitters.[87] Arash Nekoei and Andrea Weber present empirical evidence from Austria that extending unemployment benefit duration raises wages by improving reemployment firm quality.[88] Similarly, Tatsiramos studied data from European countries and found that although unemployment insurance does increase unemployment duration, the duration of subsequent employment tends to be longer (suggesting better match quality).[89]

Alternative policy

An alternative to unemployment insurance intended to reduce the moral hazard costs would introduce mandated individual saving accounts for workers to draw on after being laid off. The plan, by Martin Feldstein would pay any positive account balance at retirement to the employee.[90]

Effect on state budgets

Another issue with unemployment insurance relates to its effects on state budgets. During recessionary time periods, the number of unemployed rises and they begin to draw benefits from the program. The longer the recession lasts, depending on the state’s starting UI program balance, the quicker the state begins to run out of funds. The recession that began in December 2007 and ended in June 2009 has significantly impacted state budgets. According to The Council of State Governments, by 18 March 2011, 32 states plus the Virgin Islands had borrowed nearly $45.7 billion. The Labor Department estimates by the fourth quarter of 2013, as many as 40 states may need to borrow more than $90 billion to fund their unemployment programs and it will take a decade or more to pay off the debt.[91]

Insurance funds

Possible policy options for states to shore up the unemployment insurance funds include lowering benefits for recipients and/or raising taxes on businesses. Kentucky took the approach of raising taxes and lowering benefits to attempt to balance its unemployment insurance program. Starting in 2010, a claimant’s weekly benefits will decrease from 68% to 62% and the taxable wage base will increase from $8,000 to $12,000, over a ten-year period. These moves are estimated to save the state over $450 million.[92]

Taxing or exempting benefits

The argument for taxation of social welfare benefits is that they result in a realized gain for a taxpayer. The argument against taxation is that the benefits are generally less than the federal poverty level.

Unemployment compensation has been taxable by the federal government since 1987.[93] Code Section 85 deemed unemployment compensation included in gross income.[94] Federal taxes are not withheld from unemployment compensation at the time of payment unless requested by the recipient using Form W-4V.[93][95] In 2003, Rep. Philip English introduced legislation to repeal the taxation of unemployment compensation, but the legislation did not advance past committee.[93][96] Most states with income tax consider unemployment compensation to be taxable.[93] Prior to 1987, unemployment compensation amounts were excluded from federal gross income.[97] For the US Federal tax year of 2009, as a result of the signing of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 signed by Barack Obama on 17 February 2009 the first $2,400 worth of unemployment income received during the 'tax year' of 2009 will be exempted from being considered as taxable income on the Federal level, when American taxpayers file their 2009 IRS tax return paperwork in early 2010.

Job sharing / short-time working

Job sharing or work sharing and short time or short-time working refer to situations or systems in which employees agree to or are forced to accept a reduction in working time and pay. These can be based on individual agreements or on government programs in many countries that try to prevent unemployment. In these, employers have the option of reducing work hours to part-time for many employees instead of laying off some of them and retaining only full-time workers. For example, employees in 18 states of the United States can then receive unemployment payments for the hours they are no longer working.[98]

Payment through prepaid debit cards

In 2013, it was reported that most U.S. states deliver unemployment benefits to recipients who do not have a bank account through a prepaid debit card.[99] The federal government uses the Direct Express Debit Mastercard prepaid debit card offered by Mastercard and Comerica Bank to give some federal assistance payments to people who do not have bank accounts. Many states have similar programs for unemployment payments and other assistance.

International Labour Convention

International Labour Organization has adopted the Employment Promotion and Protection against Unemployment Convention, 1988 for promotion of employment against unemployment and social security including unemployment benefit.

See also

- Unemployment extension

- Social rights

- HIRE Act

- Reserve army of labour

- Involuntary unemployment

- Labour power

- Compensation of employees

- Lorenz curve

- Social insurance

References

- ↑ The Cabinet Papers 1915-1982: National Health Insurance Act 1911. The National Archives, 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ Bogardus, Emory S. (1950). "Group Disorganization". Sociology (3rd ed.). New York City: The Macmillan Company. p. 424.

- ↑ W. R. Garside (2002). British Unemployment 1919-1939: A Study in Public Policy. Cambridge U.P.. p. 37. ISBN 9780521892544. https://books.google.com/books?id=7TIp3oq398IC&pg=PA37.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Zimmerman, Joseph F. (1970). State and Local Government. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble. pp. 213.

- ↑ https://www.9news.com.au/national/2018/05/09/14/31/john-howard-joins-calls-for-newstart-boost

- ↑ "EI premium rates and maximums". Canada Revenue Agency. http://www.cra-arc.gc.ca/tx/bsnss/tpcs/pyrll/clcltng/ei/cnt-chrt-pf-eng.html.

- ↑ "2012 EI Monitoring and Assessment Report (Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, March 2013)". http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/eng/jobs/ei/reports/mar2012/index.shtml.

- ↑ "Public Accounts of Canada for 2012". http://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/recgen/cpc-pac/2012/index-eng.html.

- ↑ "A Look Back and A Way Forward: Actuarial Views on the Future of the Employment Insurance System, page 14(Canadian Institute of Actuaries, Nov. 2007)". http://www.actuaries.ca/members/publications/2007/207111e.pdf.

- ↑ "Public Accounts of Canada, 2008, page 4.16". http://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/recgen/pdf/49-eng.pdf.

- ↑ "A Look Back and A Way Forward: Actuarial Views on the Future of the Employment Insurance System, page 8 (Canadian Institute of Actuaries, Nov. 2007)". http://www.actuaries.ca/members/publications/2007/207111e.pdf.

- ↑ "Restoring Financial Governance and Accessibility n the Employment Insurance Program - Report of the Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills Development, Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities, page 59: Dissenting Opinion, Conservative Party of Canada - Peter Van Loan, M.P., York-Simcoe - CPC HRSDC Critic - February 09, 2005". http://cmte.parl.gc.ca/Content/HOC/committee/381/huma/reports/rp1624652/humarp03/humarp03-e.pdf.

- ↑ "Text of judgment rendered by the Supreme Court of Canada on Employment Insurance surpluses - Confédération des syndicats nationaux v. Canada (Attorney General)". http://scc.lexum.umontreal.ca/en/2008/2008scc68/2008scc68.html.

- ↑ "Social security systems in the EU". 21 Mar 2018. https://europa.eu/youreurope/citizens/work/unemployment-and-benefits/social-security/index_en.htm. Retrieved 5 Aug 2018.

- ↑ "Preconditions of earnings-related daily allowancet". YTK. http://en.ytk.fi/benefits-abc/preconditions-of-earnings-related-daily-allowance/other-preconditions. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ "Unemployment". KELA. http://www.kela.fi/in/internet/english.nsf/NET/081101150015EH?OpenDocument. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ (in French) http://www.pole-emploi.fr/candidat/le-montant-de-votre-allocation-@/suarticle.jspz?id=4125

- ↑ (in French) http://entreprise.lefigaro.fr/chomeurs-unedic.html

- ↑ (in German) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120531155700/http://www.arbeitsagentur.de/zentraler-Content/Veroeffentlichungen/Intern/Geschaeftsbericht-2011.pdf. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ "Greeks go back to basics as recession bites". BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-radio-and-tv-19289566.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "OAED Unemployment Benefits (in Greek)". ΟΑΕΔ. http://www.oaed.gr/en/2012-02-07-18-31-19/2012-02-07-18-31-52/2012-07-03-09-22-05.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "Συχνές Ερωτήσεις Επιδόματα Παροχές" (in el-GR). http://www.oaed.gr/sychnes-eroteseis-epidomata-paroches.

- ↑ "Liberal professions - Growth - European Commission" (in en). https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/promoting-entrepreneurship/we-work-for/liberal-professions_en.

- ↑ "Greece - Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion - European Commission" (in en). http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1112&langId=en&intPageId=4571.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Unemployment Benefits | Fjölmenningarsetur" (in en). http://www.mcc.is/english/work/unemployment-benefits/.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "Employment - Employment rate - OECD Data" (in en). https://data.oecd.org/emp/employment-rate.htm.

- ↑ Scruggs, Lyle (1 June 2002). "The Ghent System and Union Membership in Europe, 1970-1996". Political Research Quarterly, University of Connecticut: 275-297. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/106591290205500201.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Bowman, John R. (1952). Capitalisms Compared. CQPress. pp. 12-17.

- ↑ Andersen, Holmström, Honkapohja, Korkman, Söderström, Vartiainen (2007). "The Nordic Model". https://economics.mit.edu/files/5726.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Act of Trade Unions and Industrial Disputes". 2011. http://www.asi.is/media/249303/l-80_1938.pdf.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Unemployment benefits in Iceland" (in en). https://www.a-kasser.dk/unemployment-insurance-in-europe/iceland/.

- ↑ "Rights and obligations" (in en). https://www.vinnumalastofnun.is/en/unemployment-benefits/rights-and-obligations.

- ↑ Norðdahl, Magnús M. (1 May 2013). "Icelandic Labour Law". http://www.asi.is/media/7250/Icelandic_labour_law_-6_utg_.pdf.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 https://www.btl.gov.il/English%20Homepage/Benefits/Unemployment%20Insurance/periodofentitlement/Pages/numberofdays.aspx

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 https://www.btl.gov.il/English%20Homepage/Benefits/Unemployment%20Insurance/Pages/Conditionsofeligibility.aspx

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 https://www.btl.gov.il/English%20Homepage/Benefits/Unemployment%20Insurance/Amount/Pages/Benefitrates.aspx

- ↑ Tokyo Employment Service Centre for Foreigners website For foreign nationals working in Japan Retrieved on 23 November 2010

- ↑ "Employment insurance". http://www.justlanded.com/english/Japan/Japan-Guide/Jobs/Employment-insurance.

- ↑ Nagoya International Center Insurance Retrieved on 23 November 2010

- ↑ "Employment Insurance Law (Japan)". http://www.jil.go.jp/english/laborinfo/library/documents/llj_law11.pdf.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 Theodore, Amy. "How to Claim Unemployment Benefits in Mexico". http://www.careeraddict.com/claim-unemployment-benefits-in-mexico.

- ↑ Unemployment Benefit Manuals and Procedures - Work and Income website

- ↑ "Work and Income Unemployment Benefit Rates". http://www.workandincome.govt.nz/individuals/forms-and-brochures/benefit-rates-april-2011.html.

- ↑ Unemployment Benefit Work and Income website

- ↑ "importe maximo desempleo 2018 - Ayudas a Parados". http://www.ayudasparados.com/importe-maximo-desempleo-2012/105.

- ↑ "Request Rejected". http://www.mofa.gov.sa/Detail.asp?InSectionID=1516&InNewsItemID=1746.

- ↑ "Social Services (2) - SAMIRAD (Saudi Arabia Market Information Resource)". http://saudinf.com/main/h814.htm.

- ↑ "Jobseeker's Allowance". Directgov. http://www.direct.gov.uk/prod_consum_dg/groups/dg_digitalassets/@dg/@en/documents/digitalasset/dg_200090.html.

- ↑ Source: Benefit & Tax Credit Rates 2006 — © Citizens Advice Bureau (United Kingdom) and the Child Poverty Action Group

- ↑ "Definition of DOLE". http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/dole.

- ↑ "Best and Worst States for Unemployment Benefits - 2017 | AboutUnemployment.org" (in en-US). http://aboutunemployment.org/faqs/best-and-worst-states-for-unemployment-benefits/.

- ↑ "How to Handle a Wrongful Termination". https://www.thebalance.com/what-is-wrongful-termination-2061658.

- ↑ "Tax Topics - Topic 418 Unemployment Compensation". Internal Revenue Service. https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc418.html.

- ↑ "Here's How Long Unemployment Benefits Now Last In Each State". http://www.businessinsider.com/heres-how-long-unemployment-benefits-now-last-in-each-state-2014-1.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 55.4 55.5 55.6 "Unemployment Insurance Tax Topic, Employment & Training Administration (ETA) - U.S. Department of Labor". http://workforcesecurity.doleta.gov/unemploy/uitaxtopic.asp.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Joseph F. (1970). State and Local Government. New York, New York: Barnes & Noble. pp. 182.

- ↑ Cremieux, P. Y.; Van Audenrode, M. (6 May 1996). "Unemployment Insurance Experience Rating of Firms and Layoffs". https://ideas.repec.org/p/fth/lavape/9615.html.

- ↑ "State Unemployment Wage Bases". http://www.americanpayroll.org/members/stateui/state-ui-2/.

- ↑ "FL Dept Rev - Reemployment Tax". http://floridarevenue.com/dor/taxes/reemployment.html#who.

- ↑ igor@platon.sk, Igor Mino,. "Puerto Rico State Tax Information | Payroll Taxes". http://www.payroll-taxes.com/state-tax/puerto-rico.

- ↑ "Unemployment Insurance Tax Rates". Arizona Department of Economic Security. https://des.az.gov/sites/default/files/ui_tax_rate_chart.pdf.

- ↑ Department, Employment Development. "Rates and Withholding". http://www.edd.ca.gov/Payroll_Taxes/Rates_and_Withholding.htm.

- ↑ "Temporary Extended Unemployment Compensation". Employment & Training Administration (U.S. Department of Labor). http://workforcesecurity.doleta.gov/unemploy/factsheetteuc.asp.

- ↑ "Emergency Unemployment Compensation 2008 (EUC) Program". Employment & Training Administration (U.S. Department of Labor). http://workforcesecurity.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/euc08.pdf.

- ↑ "Unemployment Insurance Taxes and Labor Demand: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Administrative Data". SSRN Repository (Working Paper). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3062412.

- ↑ Cohen, Darrel; Follette, Glenn (1999), The Automatic Fiscal Stabilizers: Quietly Doing Their Thing, Washington, DC: Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board, http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/1999/199964/199964pap.pdf

- ↑ Lohr, Kathy (14 January 2009). "Unemployed Without Benefits: A Couple's Struggle". National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=99170822.

- ↑ http://utahstaffingcompanies.com/helpful-tips-for-employers/unemployment-benefits-eligibility/

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Labor, State of Connecticut Department of. "Unemployment Insurance Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)". https://www.ctdol.state.ct.us/progsupt/unemplt/new-faqui.htm.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 State Unemployment Benefits US Department of Labor

- ↑ Fletcher, Michael A.; Hedgpeth, Dana (9 March 2010). "Are unemployment benefits no longer temporary?". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/03/08/AR2010030804927.html.

- ↑ http://www.workforce.com/articles/penny-wise-pound-foolish-on-unemployment-challenges

- ↑ Account, Admin (15 September 2010). "To contest or not to contest: Unemployment compensation claims". http://www.accountingweb.com/aa/law-and-enforcement/to-contest-or-not-to-contest-unemployment-compensation-claims.

- ↑ "Oklahoma Employment Security Commission - Claim Statistics" (in en). https://www.ok.gov/oesc_web/Services/Unemployment_Insurance/Claim_Statistics.html.

- ↑ "ETA Press Release: Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims Report". http://www.dol.gov/opa/media/press/eta/ui/current.htm.

- ↑ Josh Boak (21 April 2016). "US applications for jobless aid fall to four-decade low". Denver Post. http://www.denverpost.com/business/ci_29795570/us-applications-jobless-aid-fall-four-decade-low?source=JPopUp. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 77.3 77.4 77.5 77.6 UI Outlook: Overview US Department of Labor

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 78.3 Rosen, Harvey S. (2008). Public Finance. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 292. ISBN 978-0-07-351128-3.

- ↑ Robert Barro, "The Folly of Subsidizing Unemployment", The Wall Street Journal, 30 August 2010.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 80.3 Would Extending Unemployment Benefits Increase Unemployment?. Simon van Zuylen-Wood. 30 November 2011

- ↑ Unemployment Insurance and Job Search in the Great Recession. Jesse Rothstein 9 September 2011

- ↑ The Blind Spot in Romney's Economic Plan Jonathan Cohn| tnr.com| 29 April 2012

- ↑ Rothstein, Jesse (2011). "Unemployment Insrance and Job Search in the Great Recession". Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 43 (2): 143–213.

- ↑ Policies for Increasing Economic Growth and Employment cbo.gov 15 November 2011

- ↑ http://www.peri.umass.edu/236/hash/10dbb94dafa96d904bcaf546ee3b02a2/publication/456/ Unemployment Benefits and Work Incentives: The U.S. Labor Market in the Great Recession (revised), Howell, David R.; Azizoglu, Bert M.; Political Economy Research Institute, 21 Mar 2011

- ↑ Marimon, Ramon (1999). "Unemployment vs. Mismatch of Talents: Reconsidering Unemployment Benefits". The Economic Journal 109 (455): 266–291. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00432.

- ↑ Mazur, Karol (2016). "Can welfare abuse be welfare improving?". Journal of Public Economics 141: 11. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2016.07.001.

- ↑ Nekoei, Arash (2017). "Does Extending Unemployment Benefits Improve Job Quality?". American Economic Review 107 (2): 527–561. doi:10.1257/aer.20150528.