Stochastic portfolio theory

Stochastic portfolio theory (SPT) is a mathematical theory for analyzing stock market structure and portfolio behavior introduced by E. Robert Fernholz in 2002. It is descriptive as opposed to normative, and is consistent with the observed behavior of actual markets. Normative assumptions, which serve as a basis for earlier theories like modern portfolio theory (MPT) and the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), are absent from SPT.

SPT uses continuous-time random processes (in particular, continuous semi-martingales) to represent the prices of individual securities. Processes with discontinuities, such as jumps, have also been incorporated* into the theory (*unverifiable claim due to missing citation!).

Stocks, portfolios and markets

SPT considers stocks and stock markets, but its methods can be applied to other classes of assets as well. A stock is represented by its price process, usually in the logarithmic representation. In the case the market is a collection of stock-price processes [math]\displaystyle{ X_i, }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ i=1, \dots, n, }[/math] each defined by a continuous semimartingale

- [math]\displaystyle{ d \log X_i(t) = \gamma_i(t) \, dt + \sum_{\nu=1}^d \xi_{i \nu}(t) \, dW_{\nu}(t) }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ W := (W_1, \dots, W_d) }[/math] is an [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-dimensional Brownian motion (Wiener) process with [math]\displaystyle{ d \geq n }[/math], and the processes [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \xi_{i \nu} }[/math] are progressively measurable with respect to the Brownian filtration [math]\displaystyle{ \{\mathcal{F}_t\} = \{\mathcal{F}^W_t\} }[/math]. In this representation [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma_i(t) }[/math] is called the (compound) growth rate of [math]\displaystyle{ X_i, }[/math] and the covariance between [math]\displaystyle{ \log X_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \log X_j }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_{ij}(t)=\sum_{\nu=1}^d \xi_{i \nu}(t) \xi_{j \nu}(t). }[/math] It is frequently assumed that, for all [math]\displaystyle{ i, }[/math] the process [math]\displaystyle{ \xi_{i,1}^2(t) + \cdots + \xi_{i d}^2(t) }[/math] is positive, locally square-integrable, and does not grow too rapidly as [math]\displaystyle{ t \rightarrow\infty. }[/math]

The logarithmic representation is equivalent to the classical arithmetic representation which uses the rate of return [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_i(t), }[/math] however the growth rate can be a meaningful indicator of long-term performance of a financial asset, whereas the rate of return has an upward bias. The relation between the rate of return and the growth rate is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_{i}(t) = \gamma_i(t) + \frac{\sigma_{ii}(t)}{2} }[/math]

The usual convention in SPT is to assume that each stock has a single share outstanding, so [math]\displaystyle{ X_i(t) }[/math] represents the total capitalization of the [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]-th stock at time [math]\displaystyle{ t, }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ X(t) = X_1(t) + \cdots + X_n(t) }[/math] is the total capitalization of the market. Dividends can be included in this representation, but are omitted here for simplicity.

An investment strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \pi = (\pi_1 , \cdots, \pi_n) }[/math] is a vector of bounded, progressively measurable processes; the quantity [math]\displaystyle{ \pi_i(t) }[/math] represents the proportion of total wealth invested in the [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]-th stock at time [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ \pi_0(t) := 1 - \sum_{i=1}^n \pi_i(t) }[/math] is the proportion hoarded (invested in a money market with zero interest rate). Negative weights correspond to short positions. The cash strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \kappa \equiv 0 (\kappa_0 \equiv 1) }[/math] keeps all wealth in the money market. A strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] is called portfolio, if it is fully invested in the stock market, that is [math]\displaystyle{ \pi_1(t) + \cdots + \pi_n (t) = 1 }[/math] holds, at all times.

The value process [math]\displaystyle{ Z_{\pi} }[/math] of a strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] is always positive and satisfies

- [math]\displaystyle{ d \log Z_{\pi}(t) = \sum_{i=1}^n \pi_i(t) \, d\log X_i(t) + \gamma_\pi^*(t) \, dt }[/math]

where the process [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma_{\pi}^* }[/math] is called the excess growth rate process and is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma_{\pi}^*(t) := \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^n \pi_i(t) \sigma_{ii}(t) -\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i,j=1}^n \pi_i(t) \pi_j(t) \sigma_{ij}(t) }[/math]

This expression is non-negative for a portfolio with non-negative weights [math]\displaystyle{ \pi_i(t) }[/math] and has been used in quadratic optimization of stock portfolios, a special case of which is optimization with respect to the logarithmic utility function.

The market weight processes,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_i(t) := \frac{X_i(t)}{X_1(t) + \cdots + X_n(t)} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ i=1, \dots, n }[/math] define the market portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math]. With the initial condition [math]\displaystyle{ Z_\mu(0) = X(0), }[/math] the associated value process will satisfy [math]\displaystyle{ Z_{\mu}(t) = X(t) }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ t. }[/math]

A number of conditions can be imposed on a market, sometimes to model actual markets and sometimes to emphasize certain types of hypothetical market behavior. Some commonly invoked conditions are:

- A market is nondegenerate if the eigenvalues of the covariance matrix [math]\displaystyle{ (\sigma_{ij} (t))_{1 \leq i,j \leq n} }[/math] are bounded away from zero. It has bounded variance if the eigenvalues are bounded.

- A market is coherent if [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{lim}_{t\rightarrow\infty} t^{-1} \log(\mu_i(t)) = 0 }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ i = 1, \dots, n. }[/math]

- A market is diverse on [math]\displaystyle{ [0, T] }[/math] if there exists [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon \gt 0 }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_{\max}(t) \leq 1 -\varepsilon }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ t \in [0, T]. }[/math]

- A market is weakly diverse on [math]\displaystyle{ [0, T] }[/math] if there exists [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon \gt 0 }[/math] such that

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{T}\int_0^T \mu_{\max}(t)\, dt \leq 1 - \varepsilon }[/math]

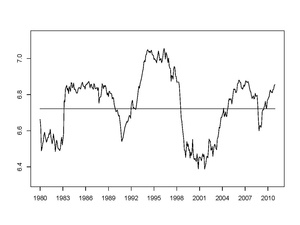

Diversity and weak diversity are rather weak conditions, and markets are generally far more diverse than would be tested by these extremes. A measure of market diversity is market entropy, defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ S(\mu(t)) = -\sum_{i=1}^{n} \mu_i(t) \log(\mu_i(t)). }[/math]

Stochastic stability

We consider the vector process [math]\displaystyle{ (\mu_{(1)}(t), \dots, \mu_{(n)}(t)), }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \leq t \lt \infty }[/math] of ranked market weights

- [math]\displaystyle{ \max_{1\leq i \leq n} \mu_i(t) =: \mu_{(1)}(t) \geq \mu_{(2)}(t) \geq \cdots \mu_{(n)}(t) := \min_{1\leq i \leq n} \mu_i(t) }[/math]

where ties are resolved “lexicographically”, always in favor of the lowest index. The log-gaps

- [math]\displaystyle{ G^{(k,k+1)}(t) := \log(\mu_{(k)}(t)/\mu_{(k+1)}(t)), }[/math]

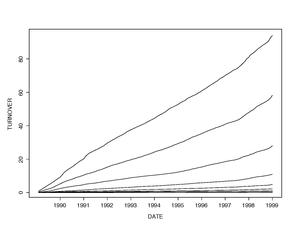

where [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \leq t \lt \infty }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ k=1, \dots, n-1 }[/math] are continuous, non-negative semimartingales; we denote by [math]\displaystyle{ \Lambda^{(k,k+1)}(t) = L^{G^{(k, k+1)}}(t ; 0) }[/math] their local times at the origin. These quantities measure the amount of turnover between ranks [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ k+1 }[/math] during the time-interval [math]\displaystyle{ [0, t] }[/math].

A market is called stochastically stable, if [math]\displaystyle{ (\mu_{(1)}(t), \cdots, \mu_{(n)}(t)) }[/math] converges in distribution as [math]\displaystyle{ t \rightarrow\infty }[/math] to a random vector [math]\displaystyle{ (M_{(1)} , \cdots, M_{(n)}) }[/math] with values in the Weyl chamber [math]\displaystyle{ \{(x_1, \dots, x_n ) \mid x_1 \gt x_2 \gt \dots \gt x_n \text{ and }\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i = 1\} }[/math] of the unit simplex, and if the strong law of large numbers

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty}\frac{\Lambda^{(k,k+1)}(t)}{t} = \lambda^{(k,k+1)} \gt 0 }[/math]

holds for suitable real constants [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda^{(1,2)}, \dots, \lambda^{(n-1, n)}. }[/math]

Arbitrage and the numeraire property

Given any two investment strategies [math]\displaystyle{ \pi,\rho }[/math] and a real number [math]\displaystyle{ T \gt 0 }[/math], we say that [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] is arbitrage relative to [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] over the time-horizon [math]\displaystyle{ [0,T] }[/math], if [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{P}(Z_\pi(T) \geq Z_\rho (T)) \geq 1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{P}(Z_\pi(T) \gt Z_\rho (T)) \gt 0 }[/math] both hold; this relative arbitrage is called “strong” if [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{P}(Z_\pi (T) \gt Z_\rho (T)) = 1. }[/math] When [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \kappa \equiv 0, }[/math] we recover the usual definition of arbitrage relative to cash. We say that a given strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \nu }[/math] has the numeraire property, if for any strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] the ratio [math]\displaystyle{ Z_\pi/Z_\nu }[/math] is a [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{P} }[/math]−supermartingale. In such a case, the process [math]\displaystyle{ 1/Z_\nu }[/math] is called a “deflator” for the market.

No arbitrage is possible, over any given time horizon, relative to a strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \nu }[/math] that has the numeraire property (either with respect to the underlying probability measure [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{P} }[/math], or with respect to any other probability measure which is equivalent to [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{P} }[/math]). A strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \nu }[/math] with the numeraire property maximizes the asymptotic growth rate from investment, in the sense that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \limsup_{T\rightarrow\infty} \frac{1}{T}\log\left(\frac{Z_\pi(T)}{Z_\nu(T)}\right) \leq 0 }[/math]

holds for any strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math]; it also maximizes the expected log-utility from investment, in the sense that for any strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] and real number [math]\displaystyle{ T \gt 0 }[/math] we have

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{E}[\log(Z_\pi(T)] \leq \mathbb{E}[\log(Z_\nu(T))]. }[/math]

If the vector [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha(t) = (\alpha_1(t), \cdots, \alpha_n(t))' }[/math] of instantaneous rates of return, and the matrix [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(t) = (\sigma(t))_{1\leq i,j \leq n} }[/math] of instantaneous covariances, are known, then the strategy

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nu(t) = \arg\max_{p \in \mathbb{R}^n} (p' \alpha(t) - \tfrac{1}{2}p' \alpha(t) p) \qquad \text{ for all } 0 \leq t \lt \infty }[/math]

has the numeraire property whenever the indicated maximum is attained.

The study of the numeraire portfolio links SPT to the so-called Benchmark approach to Mathematical Finance, which takes such a numeraire portfolio as given and provides a way to price contingent claims, without any further assumptions.

A probability measure [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Q} }[/math] is called equivalent martingale measure (EMM) on a given time-horizon [math]\displaystyle{ [0,T] }[/math], if it has the same null sets as [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{P} }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F}_T }[/math], and if the processes [math]\displaystyle{ X_1(t), \dots, X_n(t) }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \leq t \leq T }[/math] are all [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Q} }[/math]−martingales. Assuming that such an EMM exists, arbitrage is not possible on [math]\displaystyle{ [0,T] }[/math] relative to either cash [math]\displaystyle{ \kappa }[/math] or to the market portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] (or more generally, relative to any strategy [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] whose wealth process [math]\displaystyle{ Z_\rho }[/math] is a martingale under some EMM). Conversely, if [math]\displaystyle{ \pi, \rho }[/math] are portfolios and one of them is arbitrage relative to the other on [math]\displaystyle{ [0,T] }[/math] then no EMM can exist on this horizon.

Functionally-generated portfolios

Suppose we are given a smooth function [math]\displaystyle{ G : U \rightarrow (0, \infty) }[/math] on some neighborhood [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] of the unit simplex in [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^n }[/math] . We call

- [math]\displaystyle{ \pi_i^{\mathbb{G}}(t) := \mu_i(t) \left( D_i \log(\mathbb{G}(\mu(t))) + 1 - \sum_{j=1}^n \mu_j(t) D_j \log(\mathbb{G}(\mu(t))) \right) \qquad \text{ for } 1 \leq i \leq n }[/math]

the portfolio generated by the function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{G} }[/math]. It can be shown that all the weights of this portfolio are non-negative, if its generating function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{G} }[/math] is concave. Under mild conditions, the relative performance of this functionally-generated portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \pi_\mathbb{G} }[/math] with respect to the market portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math], is given by the F-G decomposition

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log\left( \frac{Z_{\pi^\mathbb{G}}(T)}{Z_{\mu}(T)} \right) = \log\left( \frac{\mathbb{G}(\mu(T))}{\mathbb{G}(\mu(0))} \right) + \int_0^T g(t) \, dt }[/math]

which involves no stochastic integrals. Here the expression

- [math]\displaystyle{ g(t) := \frac{-1}{2\mathbb{G}(\mu(t))} \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n D_{ij}^2 \mathbb{G}(\mu(t)) \mu_i(t) \mu_j(t) \tau_{ij}^\mu(t) }[/math]

is called the drift process of the portfolio (and it is a non-negative quantity if the generating function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{G} }[/math] is concave); and the quantities

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tau_{ij}^\mu(t) := \sum_{\nu=1}^n (\xi_{i\nu}(t) - \xi_\nu^\mu(t))(\xi_{j\nu}(t) - \xi_\nu^\mu(t)),\qquad \xi_{i\nu}(t) := \sum_{i=1}^n \mu_i(t) \xi_{i\nu}(t) }[/math]

with [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \leq i, j \leq n }[/math] are called the relative covariances between [math]\displaystyle{ \log (X_i) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \log (X_j) }[/math] with respect to the market.

Examples

- The constant function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{G} := w \gt 0 }[/math] generates the market portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math],

- The geometric mean function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{H}(x) := (x_1 \cdots x_n)^\frac{1}{n} }[/math] generates the equal-weighted portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_i(n) = \frac{1}{n} }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \leq i \leq n }[/math],

- The modified entropy function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{S}^c(x) = c - \sum_{i=1}^n x_i \cdot \log(x_i) }[/math] for any [math]\displaystyle{ c \gt 0 }[/math] generates the modified entropy-weighted portfolio,

- The function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{D}^{(p)}(x) := (\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^p)^\frac{1}{p} }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \lt p \lt 1 }[/math] generates the diversity-weighted portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \delta_i^{(p)}(t) = \frac{(\mu_i(t))^p}{\sum_{i=1}^n(\mu_i(t))^p} }[/math] with drift process [math]\displaystyle{ (1-p)\gamma_{\delta^{(p)}}^*(t) }[/math].

Arbitrage relative to the market

The excess growth rate of the market portfolio admits the representation [math]\displaystyle{ 2\gamma_\mu^*(t) = \sum_{i=1}^n \mu_i(t) \tau_{ii}^\mu(t) }[/math] as a capitalization-weighted average relative stock variance. This quantity is nonnegative; if it happens to be bounded away from zero, namely

- [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma_\mu^*(t) = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^n \mu_i(t) \tau_{ii}^\mu(t) \geq h \gt 0, }[/math]

for all [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \leq t \lt \infty }[/math] for some real constant [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math], then it can be shown using the F-G decomposition that, for every [math]\displaystyle{ T \gt \mathbb{S}(\mu(0))/h, }[/math] there exists a constant [math]\displaystyle{ c \gt 0 }[/math] for which the modified entropic portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \Theta^{(c)} }[/math] is strict arbitrage relative to the market [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] over [math]\displaystyle{ [0, T] }[/math]; see Fernholz and Karatzas (2005) for details. It is an open question, whether such arbitrage exists over arbitrary time horizons (for two special cases, in which the answer to this question turns out to be affirmative, please see the paragraph below and the next section).

If the eigenvalues of the covariance matrix [math]\displaystyle{ (\sigma_{ij}(t))_{1\leq i,j \leq n} }[/math] are bounded away from both zero and infinity, the condition [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma_\mu^*\geq h \gt 0 }[/math] can be shown to be equivalent to diversity, namely [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_{\max} \leq 1 - \varepsilon }[/math] for a suitable [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon \in (0, 1). }[/math] Then the diversity-weighted portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \delta^{(p)} }[/math] leads to strict arbitrage relative to the market portfolio over sufficiently long time horizons; whereas, suitable modifications of this diversity-weighted portfolio realize such strict arbitrage over arbitrary time horizons.

An example: volatility-stabilized markets

We consider the example of a system of stochastic differential equations

- [math]\displaystyle{ d\log(X_i(t)) = \frac{\alpha}{2\mu_i(t)}\, dt + \frac{\sigma}{\mu_i(t)}\, dW_i(t) }[/math]

with [math]\displaystyle{ 1\leq i \leq n }[/math] given real constants [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha \geq 0 }[/math] and an [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-dimensional Brownian motion [math]\displaystyle{ (W_1 , \dots, W_n). }[/math] It follows from the work of Bass and Perkins (2002) that this system has a weak solution, which is unique in distribution. Fernholz and Karatzas (2005) show how to construct this solution in terms of scaled and time-changed squared Bessel processes, and prove that the resulting system is coherent.

The total market capitalization [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] behaves here as geometric Brownian motion with drift, and has the same constant growth rate as the largest stock; whereas the excess growth rate of the market portfolio is a positive constant. On the other hand, the relative market weights [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_i }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \leq i \leq n }[/math] have the dynamics of multi-allele Wright-Fisher processes. This model is an example of a non-diverse market with unbounded variances, in which strong arbitrage opportunities with respect to the market portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] exist over arbitrary time horizons, as was shown by Banner and Fernholz (2008). Moreover, Pal (2012) derived the joint density of market weights at fixed times and at certain stopping times.

Rank-based portfolios

We fix an integer [math]\displaystyle{ m \in \{2, \dots, n - 1\} }[/math] and construct two capitalization-weighted portfolios: one consisting of the top [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] stocks, denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \zeta }[/math], and one consisting of the bottom [math]\displaystyle{ n - m }[/math] stocks, denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \eta }[/math]. More specifically,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \zeta_i(t) = \frac{\sum_{k=1}^m \mu_{(k)}(t) \mathbf{1}_{\{\mu_i(t) = \mu_{(k)}(t)\}}} {\sum_{l=1}^m \mu_{(l)}(t)} \qquad \text{ and } \eta_i(t) = \frac{\sum_{k=m+1}^n \mu_{(k)}(t) \mathbf{1}_{\{\mu_i(t) = \mu_{(k)}(t)\}}} {\sum_{l=m+1}^n \mu_{(l)}(t)} }[/math]

for [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \leq i \leq n. }[/math] Fernholz (1999), (2002) showed that the relative performance of the large-stock portfolio with respect to the market is given as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log\left(\frac{Z_\zeta(t)}{Z_\mu(t)}\right) = \log\left(\frac{\mu_{(1)}(T) + \cdots + \mu_{(m)}(T)} {\mu_{(1)}(0) + \cdots + \mu_{(m)}(0)} \right) - \frac{1}{2}\int_0^T \frac{\mu_{(m)}(t)}{\mu_{(1)}(t) + \cdots + \mu_{(m)}(t)} \,d\Lambda^{(m, m+1)}(t). }[/math]

Indeed, if there is no turnover at the mth rank during the interval [math]\displaystyle{ [0, T] }[/math], the fortunes of [math]\displaystyle{ \zeta }[/math] relative to the market are determined solely on the basis of how the total capitalization of this sub-universe of the [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] largest stocks fares, at time [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math] versus time 0; whenever there is turnover at the [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math]-th rank, though, [math]\displaystyle{ \zeta }[/math] has to sell at a loss a stock that gets “relegated” to the lower league, and buy a stock that has risen in value and been promoted. This accounts for the “leakage” that is evident in the last term, an integral with respect to the cumulative turnover process [math]\displaystyle{ \Lambda^{(m,m+1)} }[/math] of the relative weight in the large-cap portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \zeta }[/math] of the stock that occupies the mth rank.

The reverse situation prevails with the portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \eta }[/math] of small stocks, which gets to sell at a profit stocks that are being promoted to the “upper capitalization” league, and buy relatively cheaply stocks that are being relegated:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \log\left(\frac{Z_\eta(t)}{Z_\mu(t)}\right) = \log\left(\frac{\mu_{(m+1)}(T) + \cdots + \mu_{(n)}(T)} {\mu_{(m+1)}(0) + \cdots + \mu_{(n)}(0)} \right) + \frac{1}{2}\int_0^T \frac{\mu_{(m+1)}(t)}{\mu_{(m+1)}(t) + \cdots + \mu_{(n)}(t)}. }[/math]

It is clear from these two expressions that, in a coherent and stochastically stable market, the small- stock cap-weighted portfolio [math]\displaystyle{ \zeta }[/math] will tend to outperform its large-stock counterpart [math]\displaystyle{ \eta }[/math], at least over large time horizons and; in particular, we have under those conditions

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lim_{T\rightarrow\infty} \frac{1}{T} \log\left(\frac{Z_\eta(t)}{Z_\mu(t)}\right) = \lambda^{(m, m+1)} \mathbb{E} \left( \frac{M_{(1)}}{M_{(1)} + \cdots + M_{(m)}} + \frac{M_{(m+1)}}{M_{(m+1)} + \cdots + M_{(n)}} \right) \gt 0. }[/math]

This quantifies the so-called size effect. In Fernholz (1999, 2002), constructions such as these are generalized to include functionally generated portfolios based on ranked market weights.

First- and second-order models

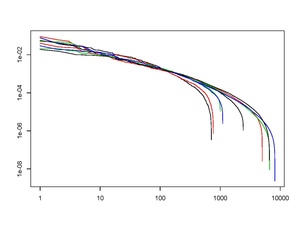

First- and second-order models are hybrid Atlas models that reproduce some of the structure of real stock markets. First-order models have only rank-based parameters, and second-order models have both rank-based and name-based parameters.

Suppose that [math]\displaystyle{ X_1,\ldots,X_n }[/math] is a coherent market, and that the limits

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\sigma}_k^2 = \lim_{t\to\infty} t^{-1}\langle\log\mu_{(k)}\rangle (t) }[/math]

and

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{g}_k = \lim_{T\to\infty}\frac{1}{T}\int_0^T\sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{1}_{\{r_t(i)=k\}}\,d\log\mu_i(t) }[/math]

exist for [math]\displaystyle{ k=1,\ldots,n }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ r_t(i) }[/math] is the rank of [math]\displaystyle{ X_i(t) }[/math]. Then the Atlas model [math]\displaystyle{ {\widehat X}_1,\ldots,{\widehat X}_n }[/math] defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ d\log {\widehat X}_i(t) = \sum_{k=1}^n \mathbf{g}_k\,\mathbf{1}_{\{{\hat r}_t(i)=k\}}\,dt + \sum_{k=1}^n\mathbf{\sigma}_k \mathbf{1}_{\{{\hat r}_t(i)=k\}}\,dW_i(t), }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ {\hat r}_t(i) }[/math] is the rank of [math]\displaystyle{ \widehat X_i(t) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ (W_1,\ldots,W_n) }[/math] is an [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-dimensional Brownian motion process, is the first-order model for the original market, [math]\displaystyle{ X_1,\ldots,X_n }[/math].

Under reasonable conditions, the capital distribution curve for a first-order model will be close to that of the original market. However, a first-order model is ergodic in the sense that each stock asymptotically spends [math]\displaystyle{ (1/n) }[/math]-th of its time at each rank, a property that is not present in actual markets. In order to vary the proportion of time that a stock spends at each rank, it is necessary to use some form of hybrid Atlas model with parameters that depend on both rank and name. An effort in this direction was made by Fernholz, Ichiba, and Karatzas (2013), who introduced a second-order model for the market with rank- and name-based growth parameters, and variance parameters that depended on rank alone.

References

- Fernholz, E.R. (2002). Stochastic Portfolio Theory. New York: Springer-Verlag.

|