Unsolved:Xingqi (circulating breath)

| Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. Circulating Breath |

|---|

Chinese Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行氣, "circulating Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. / breath") is a group of breath-control techniques that have been developed and practiced from the Warring States period (c. 475-221 BCE) to the present. Examples include Traditional Chinese medicine, Daoist meditation, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. breathing calisthenics, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. embryonic breathing, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. internal alchemy, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. internal exercises, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. deep-breathing exercises, and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. slow-motion martial art. Since the polysemous keyword Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. can mean natural "breath; air" and/or alleged supernatural "vital breath; life force", Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. signifies "circulating breath" in meditational contexts or "activating vital breath" in medical contexts.

Terminology

Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行氣) is a linguistic compound of two Chinese words:

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行) has English translation equivalents of:

- to march in order, as soldiers; walk forward ...

- to move, proceed, act; perform(ance); actor, agent; follower ...

- to engage in; to conduct; to effect, put into practice, implement ...

- pre-verbal indicator of future action, "is going to [verb]."

- temporary, transient ...

- to leave, depart from. ... (Kroll 2017: 509–510; condensed)

In Standard Chinese phonology, this character 行 is usually pronounced as rising second tone Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. above, but also can be pronounced as falling fourth tone Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行) meaning "actions, conduct, behavior, custom(ary); [Buddhism] conditioned states, conditioned things [translation of Sanskrit Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.]" or second tone Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行) "walkway, road; column, line, row, e.g., of soldiers, serried mountains, written text".

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (氣) has equivalents of:

- effluvium, vapor(ous); fumes; exhalation, breath(e).

- vital breath, pneuma, energizing breath, lifeforce, material force. ... vitality, energy; zest, spirit; zeal, gusto; inspiration; aspiration. power, strength; impelling force.

- air, aura, atmosphere; climate, weather. ... flavor; smell, scent.

- disposition, mood, spirit; temper(ament); mettle, fortitude. ... (Kroll 2017: 358; condensed)

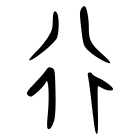

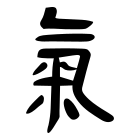

In terms of Chinese character classification, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行) was originally a pictograph of "crossroads", and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (氣) is a compound ideograph with Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (气, "air; gas; vapor") and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (米, "rice"), "气 steam rising from 米 rice as it cooks" (Bishop 2016). Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. has an uncommon variant character (炁) that is especially used in "magical" Daoist talismans, charms, and petitions.

The unabridged Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. ("Comprehensive Chinese Word Dictionary"), which is lexicographically comparable to the Oxford English Dictionary, defines Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. in three meanings:

- 道教语. 指呼吸吐纳等养生方法的内修功夫. [Daoist term. Refers to internal practices of breathing, exhaling, inhaling, and other methods of nourishing life.]

- 中医指输送精气. [Traditional Chinese medicine. Refers to conveying essence and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist..]

- 指使气血畅通. [Refers to making Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. and blood flow unobstructed.] (Luo 1994 3: 905)

There is no standard English translation of Chinese Script error: The function "transl" does not exist., as evident in:

- "leading the breath", "guiding the breath" (Maspero 1981: 283, 542)

- "circulation of the [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.]" (Needham 1983: 142)

- "circulate vapor" (Harper 1998: 125)

- "circulation of pneumas" (Campany 2002: 20)

- "circulating breath" (Despeux 2008: 1108)

- "Moving the Vapors" (Shaughnessy 2014: 190)

- "circulating the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist." (Eskildsen 2015: 254)

- "pneuma circulation" (Kroll 2017: 484)

Within this sample, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. is most often translated as "circulate/circulating/circulation", but owing to the polysemous meanings of Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. it is rendered as "breath", "vapor(s)", "pneuma(s)", or transliterated as Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.. Nathan Sivin rejected translating with the ancient Greek word Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. ("breath; spirit, soul" or "breath of life" in Stoicism) as too narrow for the semantic range of qi:

By 350 [BCE], when philosophy began to be systematic, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. meant air, breath, vapor, and other pneumatic stuff. It might be congealed or compacted in liquids or solids. Qi also referred to the balanced and ordered vitalities or energies, partly derived from the air we breathe, that cause physical changes and maintain life. These are not distinct meanings. (Sivin 1987: 47)

The term Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (氣) is "so basic to Chinese worldviews, yet so multivalent in its meanings, spanning senses normally distinguished in the West, that a single satisfying Western language translation has so far proved elusive" (Campany 2002: 18).

In Chinese medical terminology, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行氣, means "promote the circulation of qì; activate vital energy") parallels Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. or colloquial Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行血, "promote circulation of blood; activate the blood"), and is expanded in the phrasemes Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行氣散結, "set the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. in motion and disperse congelation") and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行氣, "activate vital energy and release stagnation of emotions") (tr. Bishop 2016).

Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (運氣, "control the breath; move Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. through the body"; Bishop 2016) is a near-synonym of Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行氣, "circulate the breath").

- Yùn (運) has translation equivalents of:

- turn round, revolve, circumvolve; rotate, gyre; … cyclic movement of the universe; turn of fortune or destiny; phase …

- transport, displace; move, convey; advance …

- make use of, ply, wield; handle, manage. … (Kroll 2017: 581; condensed)

When Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. is pronounced with a neutral tone, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (運氣) means "turn of events; luck, fortune, happiness".

Textual examples

Methods for circulating breath are attested during the Warring States period (c. 475-221 BCE), continued during the Han dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE), became well known during the Six Dynasties (222-589), and developed during the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) periods (Despeux 2008: 1108).

Warring States period

In the history of Daoist meditation, several Warring States texts allude to or describe breath-control meditations, but none directly mention Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行氣). Good examples are found in the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. and the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. ("Inner Training") chapter.

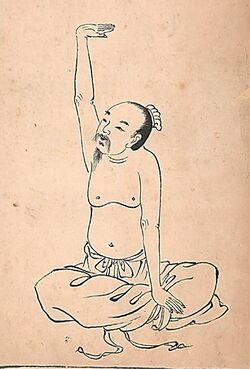

One Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. context criticizes breath exercises and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. "guiding and pulling" calisthenics: "Blowing and breathing, exhaling and inhaling, expelling the old and taking in the new, bear strides and bird stretches [熊經鳥申]—all this is merely indicative of the desire for longevity." (15, tr. Mair 1994: 145). Another context praises "breathing from the heels: "The true man of old did not dream when he slept and did not worry when he was awake. His food was not savory, his breathing was deep. The breathing of the true man is from his heels [踵], the breathing of the common man is from his throat [喉]." (6, tr. Mair 1994: 52). The Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. translator Victor Mair notes the "close affinities between the Daoist sages and the ancient Indian holy men. Yogic breath control and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (postures) were common to both traditions," and suggests that "breathing from the heels" could be "a modern explanation of the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 'supported headstand'". (1994: 371).

Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. Verse 24 summarizes Inner Training breath control, which "appears to be a meditative technique in which the adept concentrates on nothing but the Way, or some representation of it. It is to be undertaken when you are sitting in a calm and unmoving position, and it enables you to set aside the disturbances of perceptions, thoughts, emotions, and desires that normally fill your conscious mind." (Roth 1999: 116).

Expand your heart-mind and release it [大心而敢].

Relax your Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. and allow it to extend [寬氣而廣].

When your body is calm and unmoving,

Guard the One [守一] and discard myriad disturbances.

You will see profit and not be enticed by it.

You will see harm and not be frightened by it.

Relaxed and unwound, and yet free from selfishness,

In solitude you will find joy in your own being.

This is what we call "circulating the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist." [是謂雲氣].

Your awareness and practice appear celestial [意行似天]. (24, tr. Komjathy 2003: n.p.).

Translating "circulating the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist." follows Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. commentaries that interpret this original Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (雲, "cloud") as a variant Chinese character for Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (運, "transport; move"), thus reading Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (運氣, "control the breath; move Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. through the body").

Besides the Warring States-era received texts that mention breath circulation techniques, the earliest direct evidence is a Chinese jade artifact known as the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行气玉佩铭, Breath Circulation Jade Pendant Inscription) or Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行气铭, Breath Circulation Inscription). This 45-character rhymed explanation entitled Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 行氣 "circulating the (vital) breath" was inscribed on a dodecagonal block of jade, tentatively identified as either a knob for a staff or a pendant for hanging from a belt. While the dating is uncertain, estimates range from approximately middle 6th century BCE (Needham 1956: 143) to early 3rd century BCE (Harper 1998: 125). This lapidary text combines nine trisyllabic phrases describing the stages of breath circulation with four explanatory phrases. The Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. jade inscription says:

To circulate the Vital Breath [行氣]:

Breathe deeply, then it will collect [深則蓄].

When it is collected, it will expand [蓄則伸].

When it expands, it will descend [伸則下].

When it descends, it will become stable [則定].

When it is stable, it will be regular [定則固].

When it is regular, it will sprout [固則萌].

When it sprouts, it will grow [萌則長].

When it grows, it will recede [長則退].

When it recedes, it will become heavenly [退則天].

The dynamism of Heaven is revealed in the ascending [天幾舂在上];

The dynamism of Earth is revealed in the descending [地幾舂在下].

Follow this and you will live; oppose it and you will die [順則生 逆則死] (tr. Roth 1997: 298)

Han dynasty

Han dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE) historical, medical, and philosophical texts mention circulating breath.

The Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (Records of the Grand Historian), compiled by Sima Tan and his son Sima Qian from the late 2nd century BCE to early 1st century CE, says turtles and tortoises are able to practice Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.. Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. Chapter 128 Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (龜策列傳, Arrayed Traditions of Tortoise and Yarrow-stalk [Diviners]), which Chu Shaosun (褚少孫, c. 104-30 BCE) appended with a text on sacred tortoises used in plastromancy, claims that the longevity of tortoises results from Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. breath circulation and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. calisthenics: "An old man in south used a tortoise as a leg for his bed, and died after more than ten years. When his bed was removed, the tortoise was still alive. Tortoises are able to practice breath circulation and calisthenics [南方老人用龜支床足 行十餘歲 老人死 移床 龜尚生不死 龜能行氣導引].

Ge Hong's 4th-century Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (below) quotes Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 128 with a different version of this tortoise-bed legend [江淮閒居人為兒時 以龜枝床 至後老死 家人移床 而龜故生], with young rather than old men.

When the men living between the Yangtze and the Huai are young, they place their beds on tortoises, and their families do not remove the beds until those boys have died of old age." Thus, these animals have lived at least fifty or sixty years, and, given that they can dispense this long with food or drink and still not die, it shows that they are far different from common creatures. Why should we doubt that they can last a thousand years? Isn't there good reason for the Genii Classics to suggest we imitate the breathing of the tortoise? (3, tr. Ware 1966: 56-57)

Another interpretation is putting a tortoise into, rather than on a bed. "It is allegedly common in the area of the Yangtse and the Huai to put a tortoise into the bed in childhood; when people die of old age, the tortoise is still alive. (tr. Eberhard 1968: 321). This Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. context repeatedly mentions cranes and tortoises (Chinese exemplars of longevity) using Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. calisthenics without Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.. For instance, "Knowing the great age attained by tortoises and cranes, he imitates their calisthenics so as to augment his own life span" (Ware 1966: 53); "Therefore, God's Men merely ask us to study the method by which these animals extend their years through calisthenics and to model ourselves on their eschewing of starches through the consumption of breath" (1966: 58); "the tortoise and the crane have a special understanding of calisthenics and diet" (1966: 59).

The c. 2nd-century to 1st-century BCE Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor) uses Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行氣) five times in the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (素問, Basic Questions) and three in the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (靈樞, Spiritual Pivot) sections. For instances, the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (經脈別論, Treatise on How to Distinguish the Vascular System) section says,

The force of the pulse flows into the arteries (經) and the force of the arteries ascends into the lungs; the lungs send it into all the pulses (百脈), which then transport its essence to the skin and the body hair. The entire vascular system unites with the secretions [毛脈合精] and passes the force of life on to a storehouse [行氣於腑], which stores the energy and vitality and intelligence. These are then transmitted to the four (parts of the body), and the vital forces of the viscera are restored to their order. (21, tr. Veith 1949: 196)

And Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (太陰陽明論, Treatise on the Region of the Great Tin and on the Region of the 'Sunlight') says,

The Great Yin of the foot means (relates to) the three Yin. Its communication by way of the stomach is subject to the spleen and is connected with the throat; thus it is the great Yin which causes the communication to the three parts of Yin [故太陰為之行氣於三陰]. … The five viscera and the six hollow organs are like an ocean (a reservoir 海). They also serve to transport vigor to the three regions of Yang [亦為之行氣於三陽]. The viscera and the hollow organs, in reliance upon their direct communication, receive vigor from the region of the 'sunlight'. Thus they cause the stomach to transport its fluid secretions. (29, tr. Veith 1949: 235-236)

The c. 139 BCE Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. is a Chinese collection of essays that blends Daoist, Confucianist, and Legalist concepts, especially including yin and yang and Wuxing (Five Phases/Agents) theories. In particular, the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (五臟, Five Orbs/Viscera; heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys)are important to the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. because they provide a conceptual bridge among the cosmic, physiological, and cognitive realms. In medical theory, each of the Five Orbs was correlated with one of the Five Phases of Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. and was understood to be responsible for the generation and circulation of its particular form of Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. throughout the mind-body system." (Major 2010: 900). Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. does not occur in this eclectic text but the "Originating in the Way" chapter describes circulating blood and qi: "The mind is the master of the Five Orbs. It regulates and directs the Four Limbs and circulates the blood and vital energy [流行血氣], gallops through the realms of accepting and rejecting, and enters and exits through the gateways and doorways of the hundreds of endeavors. (1.17, tr. Major 2010: 71; cf. 7.3, 2010: 243).

The c. 1st-century CE Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. text, which is traditionally attributed to Ban Gu (32–92 CE), frequently mentions the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (Five Elements or Five Phases). Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (天行氣, Heavenly Circulation of Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.) occurs in The Five Elements section explaining the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行) in wuxing: "What is meant by the 'Five Elements' Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. [五行]? Metal, wood, water, fire, and earth. The word Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. is used to bring out the meaning that [in accordance] with Heaven the fluids have been 'put into motion' Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. [天行氣]." (tr. Tjan 1952: 429). Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (五行氣, Five-Phases Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.) occurs in the "Instinct and Emotion" section: "Why are there five Instincts [五性] and six Emotions [六情]? Man by nature lives by containing the fluids of the Six Pitch-pipes [六律] and the Five Elements [五行氣]. Therefore, he has in [his body] the Five Reservoirs [五藏] and the Six Storehouses [六府], through which the Instincts and Emotions go in and out." (tr. Tjan 1952: 566).

Six dynasties

The historical term "Six Dynasties" collectively refers to the Three Kingdoms (220–280 CE), Jin Dynasty (265–420), and Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589).

The c. 3rd-4th century Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (黃庭經, "Scripture of the Yellow Court") contrasts the respiration of ordinary people and Daoists inhaling through the nose and exhaling through the mouth. Ordinary people's breath supposedly descends from the nose to the kidneys, traverses the Five Viscera (kidneys, heart, liver, spleen, and lungs), then the Six Receptacles (gall bladder, stomach, large intestine, small intestine, triple burner, and bladder), where it is blocked by the "Origin of the Barrier, [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 關元, the Bl-26 acupuncture point], the double door of which is closed with a key and guarded by the gods of the spleen, both clad in red," whereupon the breath rises to the mouth and is exhaled (Maspero 1981: 341). Daoist adepts knew how to control their breath to open these doors and lead it to the Lower Cinnabar Field or Ocean of Breath [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 氣海], three inches below the navel.

Then is the moment of "leading the breath", [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.], in such a way that "the breaths of the Nine Heavens (= the inhaled air), which have entered the man's nose, make the tour of the body and are poured into the Palace of the Brain". The "breath is led" by Interior Vision, [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.], thanks to which the Adept sees the inside of his own body and, concentrating his thought, steers the breath and guides it, following it by sight through all the veins and passages of the body. Thus it is led where one wishes. If one is sick (that is, if some passage inside the body is obstructed and hampers the regular passage of air), that is where one leads it to reestablish circulation, which produces healing.

The adept then circulates the Ocean of Breath to ascend the spinal column into the Upper Cinnabar Field (brain), go back down to the Middle Cinnabar Field (heart), when it is expelled by the lungs and goes out through the mouth. (Maspero 1981: 342).

The Jin dynasty Daoist scholar Ge Hong's 318 Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. ("Master Who Embraces Simplicity") frequently mentions xingqi; written (行氣, with the standard Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. character) 13 times and (行炁, with the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. variant character typically used in magical Daoist talismans) 11 times. In this text, the term Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. "loosely designates various practices in which breath is swallowed and then systematically circulated (often guided by visualization) throughout the body. Such practices were often understood as substituting pure cosmic pneumas for ordinary foods (especially grains and meats) as the staples of one's diet." (Campany 2002: 133). In several of Ge Hong's discussions of the sexual arts of self-cultivation, his consistent position is that they, "along with the circulation of pneumas, are necessary supplements [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 補] to the ingestion of elixirs for the attainment of transcendence." (Campany 2002: 31).

Chapter 8 (釋滯 "Resolving Hesitations") provides more detailed information about Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. than any other Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. chapter. First, breath circulation should be practiced along with controlling ejaculation and taking Daoist drugs.

If you wish to seek divinity or geniehood [i.e., xian transcendence], you need only acquire the quintessence, which consists in treasuring your sperm [寶精], circulating your breaths [行炁], and taking one crucial medicine [服一大藥]. That is all! There are not a multitude of things to do. In these three pursuits, however, one must distinguish between the profound and the shallow. You cannot learn all about them promptly unless you meet with a learned teacher and work very, very hard. Many things may be dubbed circulation of the breaths, but there are only a few methods for doing it correctly. Other things may be dubbed good sexual practice, but its true recipe involves almost a hundred or more different activities. Something may be dubbed a medicine to be taken, but there are roughly a thousand such prescriptions. (8, tr. Ware 1966: 138).

Second, Ge Hong lists the supernatural powers of Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. and connects it with Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. embryonic breathing.

Through circulation of the breaths [行炁] illnesses can be cured, plague need not be fled, snakes and tigers can be charmed, bleeding from wounds can be halted, one may stay under water or walk on it, be free from hunger and thirst, and protract one's years. The most important part of it is simply to breathe like a fetus [胎息]. He who succeeds in doing this will do his breathing as though in the womb, without using nose or mouth, and for him the divine Process has been achieved. (8, tr. Ware 1966: 138-139),

Third, he describes how a beginning Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. breath circulation practitioner should count their heartbeats to measure time during Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (閉氣, "breath holding").

When first learning to circulate the breaths, one inhales through the nose and closes up that breath. After holding it quietly for 120 heartbeats [approximately 90 seconds], it is expelled in tiny quantities through the mouth. During the exhalations and inhalations one should not hear the sound of one's own breathing, and one should always exhale less than one inhales. A goose feather held before the nose and mouth during the exhalations should not move. After some practice the number of heartbeats may be increased very gradually to one thousand [approx. 12 minutes 30 seconds], before the breath is released. Once this is achieved, the aged will become one day younger each day. (8, tr. Ware 1966: 138-139; times estimated by Needham 1983: 143-144)

The current world record for static apnea (without prior breathing of 100% oxygen) is 11 minutes and 35 seconds (Stéphane Mifsud, 8 June 2009).

Fourth, using the ancient Chinese daily division between Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (生炁, "living breath", from midnight to noon) and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (死炁, "dead breath", from noon to midnight), it warns, "The circulating of the breaths must be done at an hour when breath is alive, not when it is dead. … No benefit is derived from practicing the circulating when breath is dead." (8, tr. Ware 1966: 139). Fifth, Ge advises maintaining moderation and tells an anecdote about his great-uncle Ge Xuan (164-244), a legendary Daoist who first received the Lingbao School scriptures.

It must be admitted, however, that it is man's nature to engage in multiple pursuits and he is little inclined to the peace and quiet requisite to the pursuit of this process. For the circulation of the breaths it is essential that the processor refrain from overeating. When fresh vegetables, and fatty and fresh meats are consumed, the breaths, becoming strengthened, are hard to preserve. Hate and anger are also forbidden. Overindulgence in them throws the breaths into confusion, and when they are not calmed they turn into shouting. For these reasons few persons can practice this art. My ancestral uncle, Ko Hsüan, merely because he was able to hoard his breaths and breathe like a fetus, would stay on the bottom of a deep pool for almost a whole day whenever he was thoroughly intoxicated and it was a hot summer's day. (8, tr. Ware 1966: 140).

Compare the above claim that with breath circulation, "one may stay under water or walk on it."

The Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. repeatedly describes practicing Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. breath circulation along with other longevity techniques, such as drug consumption and Daoist sexual practices above, which warns "one must distinguish between the profound and the shallow". Another context compares these same three methods.

The taking of medicines [服藥] may be the first requirement for enjoying Fullness of Life [長生], but the concomitant practice of breath circulation [行氣] greatly enhances speedy attainment of the goal. Even if medicines [神藥] are not attainable and only breath circulation is practiced, a few hundred years will be attained provided the scheme is carried out fuIly, but one must also know the art of sexual intercourse [房中之術] to achieve such extra years. If ignorance of the sexual art causes frequent losses of sperm to occur, it will be difficult to have sufficient energy to circulate the breaths. (5, tr. Ware 1966, 105).

Chapter 8 mentions the inherent dangers for Daoist adepts who overspecialize in studying a particular technique.

In everything pertaining to the nurturing of life [養生] one must learn much and make the essentials one's own; look widely and know how to select. There can be no reliance upon one particular specialty, for there is always the danger that breadwinners will emphasize their personal specialties. That is why those who know recipes for sexual intercourse [房中之術] say that only these recipes can lead to geniehood. Those who know breathing procedures [吐納] claim that only circulation of the breaths [行氣] can prolong our years. Those knowing methods for bending and stretching [屈伸] say that only calisthenics can exorcize old age. Those knowing herbal prescriptions [草木之方] say that only through the nibbling of medicines can one be free from exhaustion. Failures in the study of the divine process are due to such specializations. (8, tr. Ware 1966: 113).

In a final example, Ge Hong gives practical advice for avoiding illness.

If you are going to do everything possible to nurture your life [養生], you will take the divine medicines [神藥]. In addition, you will never weary of circulating your breaths [行氣]; morning and night you will do calisthenics [導引] to circulate your blood and breaths and see that they do not stagnate. In addition to these things, you will practice sexual intercourse in the right fashion [房中之術]; you will eat and drink moderately; you will avoid drafts and dampness; you will not trouble about things that are not within your competence. Do all these things, and you will not fall sick. (15, tr. Ware 1966: 252)

Taking a fundamentally pragmatic position on yangsheng Nourishing Life practices, Ge Hong believes that "the perfection of any one method can only be attained in conjunction with several others." (Engelhardt 2000: 77).

While several Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. contexts mention healing oneself with breath circulation, one records using it to heal another person. During the Eastern Wu dynasty (222-280), there was a Daoist master named Shi Chun (石春) "who would not eat in order to hasten the cure when he was treating a sick person by circulating his own breath. It would sometimes be a hundred days or only a month before he ate again." When Emperor Jing of Wu (r. 258–364) heard about this he said, "In a short time this man is going to starve to death", and ordered that Shi be locked up and guarded constantly without food or water, excepting a few quarts he requested for making holy water. After more than a year of imprisonment, his "complexion became ever fresher and his strength remained normal." The emperor then asked him how much longer he could continue like this, and Shi Chun replied that "there was no limit; possibly several dozen years, his only fear being that he might die of old age, but it would not be of hunger." The emperor discontinued the fasting experiment and released him (15, tr. Ware 1966: 248–249). The Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. bibliography of Daoist texts lists the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行氣治病經, Scripture on Treating Illness with Breath Circulation), which was subsequently lost.

Besides the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist., Ge Hong also compiled the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (Biographies of Divine Transcendents), in which ten hagiographies mention adepts practicing Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. along with other methods and techniques.

- Peng Zu "lived past eight hundred; ate cassia and mushrooms; and excelled at 'guiding and pulling' (Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.) and at circulating pneumas." (Campany 2002: 182). In another textual version, "If there was any illness, fatigue, or discomfort in his body, he would 'guide and pull' (導引) and shut off his breath so as to attack what was troubling him. He would fix his heart by turns on each part of his body: his head and face, his nine orifices and five viscera, his four limbs, even his hair. In each case he would cause his heart to abide there, and he would feel his breath circulate throughout his body, starting at his nose and mouth and reaching down into his ten fingers." (Campany 2002: 417).

- Laozi "made available many methods for transcending the world, including, [first of all,] [formulas for] nine elixirs and eight minerals, Liquor of Jade and Gold Liquor; next, methods for mentally fixing on the mystic and unsullied, meditating on spirits and on the Monad [守一], successively storing and circulating pneumas, refining one's body and dispelling disasters, averting evil and controlling ghosts, nourishing one's nature and avoiding grains, transforming oneself [so as to] overcome trouble, keeping to the teachings and precepts, and dispatching demons" (Campany 2002: 199).

- Liu Gen (劉根) "eventually taught Wang Zhen [王真] how to meditate on the Monad, circulate pneumas, and visualize [his corporeal] spirits, and also methods for sitting astride the Mainstays and Strands [of the heavens] and for confessing one's transgressions and submitting one's name on high." (Campany 2002: 246–248).

- Gan Shi (甘始) "excelled at circulating pneumas. He did not eat [a normal diet] but ingested [only] asparagus root [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 天門冬]." (Campany 2002: 150)

- Kong Anguo "habitually circulated pneumas and ingested lead and cinnabar (or "an elixir made from lead"). He reached three hundred years of age and had the appearance of a boy" (Campany 2002: 311).

- Bo He (帛和) received from the physician Dong Feng his "methods of circulating pneumas, ingesting atractylis, and avoiding grains" (tr. Campany 2002: 133).

- She Zheng (涉正) transmitted to all his disciples "[methods of] circulating pneumas, bedchamber [arts], and the ingestion of a lesser elixir made from 'stony brains' [geodes]." (Campany 2002: 332).

- Zhang Ling (c. 34–156) " As for his circulation of pneumas and dietetic regimen, he relied on [standard] methods of transcendence; here, [as with methods of curing illness], he made no significant changes." (Campany 2002: 352).

- Dong Zhong (董仲) "From his youth he practiced pneuma circulation and refined his body. When he had reached an age of over a hundred, he still had not aged [in appearance]." (Campany 2002: 363).

- Huang Jing (黄敬) "is said to have circulated pneumas, abstained from grains, subsisted on his saliva, practiced embryonic breathing and interior vision, summoned the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. and jade maidens, and swallowed talismans of yin and yang." (Campany 2002: 541).

Tang dynasty

During the Tang dynasty (618-907), Daoists integrated new meditation theories and techniques from Chinese Buddhism and many seminal texts were written, especially during the 8th century.

The Daoist Shangqing School patriarch Sima Chengzhen 司馬承禎, 647–735) composed the 730 Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (服氣精義論, Essay on the Essential Meaning of Breath Ingestion), which presented integrated outlines of health practices, with both traditional Chinese physical techniques and the Buddhist-inspired practice of guan (觀, "insight meditation"), as preliminaries for attaining and realizing the Dao (Engelhardt 2000: 80). The text is divided into nine sections (Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 論, "essays; discourses") describing the consecutive steps toward attaining purification and longevity.

The second section "On the Ingestion of Breath" (Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 服氣論) gives several methods for adepts to become independent of ordinary breathing, first absorb Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. as breath, then guide it internally, and store it in their inner organs. Adepts begin by absorbing the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 太清行氣符, Great Clarity Talisman for [Facilitating] Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. Circulation), which enables one to gradually abstain from eating grains. They then ingest Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. by visualizing the first rays of the rising sun, guide it through the body and viscera, until they can permanently "retain the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.". Sima Chengzhen points out that when one begins abstaining from foods and survives only by ingesting Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. breath (and repeats this warning for taking drugs), the immediate effect will be undergoing a phase of weakening and decay, but eventually strength returns all illnesses vanish. Only after nine years of further practice will an adept rightfully be called a zhenren ("Realized One; Perfected Person"). (Englehardt 1989: 273).

The Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (太清王老服氣口訣, The Venerable Wang's Instructions for Absorbing Qi, a Taiqing Scripture) differentiates two methods of breath circulation.

There were two ways of making it circulate [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 運氣]. Concentrating the will to direct it to a particular place, such as the brain, or the site of some local malady, was termed [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 行氣]. Visualising its flow in thought was "inner vision" [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 內視, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 內觀], differentiated (not very convincingly to us) from ordinary imagination. "Closing one's eyes, one has an inner vision of the five viscera, one can clearly distinguish them, one knows the place of each…" (Needham 1983: 148).

The c. 745 Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (延陵先生集新舊服氣經, Scripture on New and Old Methods for the Ingestion of Breath Collected by the Elder of Yanling) defines the technique: "One must carefully pull the breath while inspiring and expiring so that the Original Breath (Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 元氣) does not exit the body. Thus, the outer and inner breaths do not mix and one achieves embryonic breathing" (tr. Despeux 2008: 953). This source also recommends the "method of the drum and of effort" (Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 鼓努之法) Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. breath circulation for creating a Sacred Embryo.

At the times when you are guiding the Breath, beat the drum [a technical term meaning "grit the teeth"] and perform ten swallowings, twenty swallowings, so that your intestines are filled. After that concentrate upon guiding (the Breath) and making it penetrate into the four limbs. When you are practicing this method, guide the Breath once for each time you swallow. The hands and feet should be supported on things; wait until the Breath has penetrated, and then the heart must be emptied and the body forgotten; and thereupon the hot breath [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 煩蒸之氣] will be dispersed throughout the four limbs; the breath of the Essential Flower [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 精華之氣], being coagulated, will return to the Ocean of Breath [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 氣海]. After some time, the Embryo will be completed spontaneously. By holding the joints of the members firm, you can succeed in having (the Breaths) answer one another with the sound of thunder; the drum resounds in the belly so that the Breaths are harmonized. "(tr. Maspero 1981: 481)

Li Fengshi's (李奉時) c. 780 Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (嵩山太無先生氣經, Mr. Grand-Nothingness of Song Mountain's Scripture on Breath) discusses how one's Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (意, "intention; will") plays a major role in circulating breath (Despeux 2008: 1108). For instance, using Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. breath-holding to heal oneself.

If suddenly there is discomfort in cultivating and nourishing (the breath) or occasionally there is some kind of illness, go into a secluded room and follow this method: spread out your hands and feet, then harmonize the breath and swallow it down (guiding it in your thoughts) to where the trouble is. Shut off the breath. Use the will and the mind to regulate the breath in order to attack the ailment. When the breath has been retained to the extreme, exhale it. Then swallow it again. If the breathing is rapid, stop. If the breath is harmonious, work on the ailment again. … Even if the ailment is in your head, face, hands or feet, wherever it is, work on it. There is nothing that will not be cured. Note that when the mind wills the breath into the limbs, it works like magic, its effects are indescribable. (tr. Huang 1988: 22)

The Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (行氣訣, Secret of Guiding the Breath) chapter describes circulating breaths between the upper and lower Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (丹田, "elixir fields"): Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (泥丸丹田, "muddy pellet elixir-field", or Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 腦宮 "brain palace") and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (下丹田, "lower elixir-field", above the perineum).

There are two points on the spine behind the lower [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.]. They correspond through the ridge vein with the [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.] which is the brain palace (a point between the eyes above the root of the nose). The Original Breath [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.] is obtained by storing (the breath of) every three consecutive swallowings in the lower [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.]. Use the mind to take (the Original Breath) in and to make it enter the two points. (You should) imagine two columns of white breath going straight up on both sides of your spine and entering the [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.] to becloud thickly the palace. Then the breath continues to your hair, your face, your neck, both arms and hands up and to your fingers. After a little time, it enters the chest and the middle [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.] which is (by) the heart. It pours on into the five viscera, it passes the lower [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.], and reaches [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 三里] (the Three Miles, i.e., the genitals) It goes through your hips, your knees, ankles and all the way to the [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 涌泉] (acupuncture points) which are in the center of your feet soles. That is the so-called [謂分一氣而理] "to share one breath and manage it individually". (tr. Huang 1988: 18-19)

The late 8th-century Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (太無先生氣服氣) explains how to circulate the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. Original Breath. Tang Daoist practitioners fundamentally changed the nature and understanding of Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. Embryonic Breathing from the ancient theory of Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 外氣), "external Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. of the air; external breathing") to the new theory of Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (內氣, "internal Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.") of one's organs; internal breathing"). Instead of inhaling and holding Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. breath, adepts would circulate and remold visceral Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. energy, which was believed to recreate the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (元氣 "prenatal qi; primary vitality") received at birth and gradually depleted during human life.

According to the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist., since it is the Original Breath and not external breath which must be kept circulating through the body, and since its natural place is within the body, there is no need to make it enter or hold it in by effort as the ancients did: no retention of the breath, which is exhausting and, in some cases, harmful. But it does not follow that to make the breath circulate is an easy thing; on the contrary, it requires a lengthy apprenticeship. "The internal breath... is naturally in the body, it is not a breath which you go outside to seek; (but) if you do not get the explanations of an enlightened master, (all efforts) will be nothing but useless toil, and you will never succeed." Common ordinary respiration plays only a secondary role in the mechanism of Breath circulation, which goes on outside it. The two breaths, internal and external, carry on their movements in perfect correspondence. When the external breath ascends during inhalation, the internal breath contained in the lower Cinnabar Field also rises; when the external breath descends, the internal breath descends too and returns again to the lower Cinnabar Field. Such is the simple mechanism which governs the circulation of Original Breath. (Maspero 1981: 468)

This is done in two phases: "swallowing the breath" [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 咽氣] and making it circulate. And if there is only a single way of absorbing the Breath, there are two distinct ways of making it circulate. One consists of leading it so as to guide it where one wishes it to go, to an afflicted area if it is to cure a malady, to the [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.] if Embryonic Respiration is the purpose, and so on. This is what is called "guiding the breath" [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.]. The other consists of letting the breath go where it will through the body without interfering by guiding it. This is what is called "refining the breath" [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.]. I shall point out in succession the methods for absorbing the breath, for guiding it, and for refining it. It is the first of these two pulses. Absorbing the Breath, which is properly to be called Embryonic Respiration [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.]: but the expression is applied also to the exercises in toto. (Maspero 1981: 469–470).

Song dynasty

Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. breath circulation continued developing during the Song (960-1279).

Among the many progressive series of Daoist breath-circulating exercises ascribed to famous masters such as Chisongzi and Pengzu, one more complex set is attributed to the lesser-known Master Ning, the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (寧先生導引法, Master Ning's Gymnastic Method). According to traditions, Master Ning was the Yellow Emperor's Director of Potters (Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 陶正). "He could gather up fire and not burn himself, and he went up and down with the smoke; his clothes never burned." (Maspero 1981: 543). His method "was a series of magical procedures endowed with a specific efficacy, allowing one to go into fire without being burned and into water without drowning, in imitation of Master Ning himself. It included a method of guiding the breath, [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.], and contained four series of exercises in which rhythmic breathing, retention of breath, and movements of arms, legs, head, and torso were done successively." Each of these series was named after a particular animal: the breath-guiding procedures of the Toad, Tortoise, Wild Goose, and Dragon, with exercises representing the movements and breathing of these animals. For instance, the "Dragon Procedure of Circulating the Breath":

- Bow the head and look down; remain without breathing (the equivalent of) twelve (respirations).

- With both hands massage from the belly down to the feet; take the feet and pull them up to under the arms; remain without breathing (the equivalent of) twelve (respirations).

- Place the hands on the nape of the neck and clasp them there" (Maspero 1981: 549–550).

Ceng Cao's (曾造) 12th-century Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. quotes Master Ning: "Guiding the Breath, [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.], controls the inside, and Gymnastics, [Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.], controls the outside." (tr. Maspero 1981: 542).

See also

- Anapanasati, Buddhist mindfulness of breathing

- Pranayama, Yogic technique for controlling breath

References

- Bishop, Tom (2016), Wenlin Software for learning Chinese, version 4.3.2.

- Campany, Robert Ford (2002), To Live as Long as Heaven and Earth: A Translation and Study of Ge Hong's Traditions of Divine Transcendents, University of California Press.

- Despeux, Catherine (2008), "Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. 行氣 Circulating Breath," in Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Taoism, Routledge, 1108.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (1968), The Local Cultures of South and East China, Alide Eberhard, tr. Lokalkulturen im alten China, 1943, E.J. Brill.

- Engelhardt, Ute (2000), "Longevity Techniques and Chinese Medicine," in Kohn Daoism Handbook, E. J. Brill, 74-108.

- Eskildsen, Stephen (2015), Daoism, Meditation, And the Wonders of Serenity – From the Latter Han Dynasty (25-220) to the Tang Dynasty (618-907), SUNY Press.

- Harper, Donald (1998), Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts, Kegan Paul.

- Huang, Jane (1998), The Primordial Breath: An Ancient Chinese Way of Prolonging Life through Breath Control, revised ed., 2 vols., Original Books.

- Komjathy, Louis (2003), Handbooks for Daoist Practice (Complete Series: 10 Volumes), Yuen Yuen Institute.

- Kroll, Paul W. (2017), A Student's Dictionary of Classical and Medieval Chinese (rev. ed.), E.J. Brill.

- Luo Zhufeng 羅竹風, chief ed., (1994), Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. ("Comprehensive Dictionary of Chinese"), 13 vols. Shanghai cishu chubanshe.

- Mair, Victor H., tr. (1994), Wandering on the Way, Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu, Bantam.

- Major, John S., Sarah Queen, Andrew Meyer, and Harold D. Roth (2010), The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China, Columbia University Press.

- Maspero, Henri (1981), Taoism and Chinese Religion, tr. by Frank A. Kierman, University of Massachusetts Press.

- Needham, Joseph and Wang Ling (1956), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 2, History of Scientific Thought, Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph and Lu Gwei-djen (1983), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Part 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Physiological Alchemy, Cambridge University Press.

- Roth, Harold D. (1997), "Evidence for Stages of Meditation in Early Taoism", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 60.2: 295–314.

- Roth, Harold D. (1999), Original Tao: Inward Training (Nei-yeh) and the Foundations of Taoist Mysticism, Columbia University Press.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (2014), "Unearthing the Changes: Recently Discovered Manuscripts of the Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.) and Related Texts", Columbia University Press.

- Sivin, Nathan (1987), Traditional, Chinese Medicine in Contemporary China. Science, Medicine, and Technology in East Asia, vol. 2., University of Michigan.

- Tjan Tjoe Som (1952), Po Hu T'ung - The Comprehensive Discussions in the White Tiger Hall, E. J. Brill.

- Veith, Ilza. Tr. (1949), The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine, University of California Press.

- Ware, James R., tr. (1966), Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The Nei Pien of Ko Hung, Dover.

External links

- 嵩山太無先生氣經, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. ("Mr. Grand-Nothingness of Song Mountain's Scripture on Breath [Circulation])), Wikisource edition.

- Body Scan Meditation, Jon Kabat-Zinn, modern example of breath circulation

|