Religion:Jain Scriptures

| Jain Scriptures | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Sects | Jain Agamas |

| Digambara | Jain Agamas (Digambara) | |

| Śvētāmbara | Jain Agamas (Śvētāmbara) | |

Agama is a Sanskrit word which signifies the 'coming' of a body of doctrine by means of transmission through a lineage of authoritative teachers. They are believed to have been verbally transmitted by the oral tradition from one generation to the next, much like the ancient Buddhist and Hindu texts.[2] The Jain tradition believes that their religion is eternal, and the teachings of their first Tirthankara Rishabhanatha were their scriptures millions of years ago.[3] The religion states that the tirthankara taught in a divine preaching hall called samavasarana, which were heard by the gods, the ascetics and laypersons.

According to the Jain tradition, an araha (worthy one) speaks meaning that is then converted into sūtra (sutta) by his disciples, and from such sūtras emerge the doctrine.[4] The creation and transmission of the Agama is the work of disciples in Jainism. These texts, historically for Jains, have represented the truths uttered by their tirthankaras, particularly the Mahāvīra.[4] In every cycle of Jain cosmology, twenty-four tirthankaras appear and so do the Jain scriptures for that ara.[3] The spoken scriptural language is believed to be Ardhamagadhi by the Śvētāmbara Jains, and a form of sonic resonance by the Digambara Jains. These then become coded into duvala samgagani pidaga (twelve limbed baskets by disciples), but transmitted orally.[2] In the 980th year after Mahāvīra's death (~5th century CE), the texts were written down for the first time by the Council of Valabhi.[5]

The Śvētāmbaras believe that they have the original Jain scriptures. The Śvētāmbara belief is denied by the Digambaras, who instead believe the scriptures were lost.[4][6] The Śvētāmbaras state that their collection of 45 works represent a continuous tradition, though they accept that their collection is also incomplete because of a lost Anga text and four lost Purva texts.[7] The Digambara sect of Jainism believes that Āchārya Bhutabali was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original canon. According to them, Digambara Āchāryas recreated the oldest-known Digambara Jain texts, including the four anuyoga.[8][9][10] According to von Glasenapp, the Digambara texts partially agree with the enumerations and works of older Śvētāmbara texts, but in many cases there are also gross differences between the texts of the two major Jain traditions.[6]

The Śvētāmbara consider their 45 text collection as canonical.[7] The Digambaras created a secondary canon between 600 and 900 CE, compiling it into four groups: history, cosmography, philosophy and ethics.[11] This four-set collection is called the "four Vedas" by the Digambaras.[11][note 1]

The most popular and influential texts of Jainism have been its non-canonical literature. Of these, the Kalpa Sūtras are particularly popular among Śvētāmbaras, which they attribute to Bhadrabahu (c. 300 BCE). This ancient scholar is revered in the Digambara tradition, and they believe he led their migration into the ancient south Karnataka region, and created their tradition.[13] Śvētāmbaras disagree, and they believe that Bhadrabahu moved to Nepal, not into peninsular India.[13] Both traditions, however, consider his Niryuktis and Samhitas as important texts. The earliest surviving Sanskrit text by Umaswati called the Tattvarthasūtra is considered authoritative Jain philosophy text by all traditions of Jainism. [14][15][16] His text has the same importance in Jainism as Vedanta Sūtras and Yogasūtras have in Hinduism.[17][14][18]

In the Digambara tradition, the texts written by Kundakunda are highly revered and have been historically influential.[19][20][21] Other important Jain texts include: Samayasara, Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra, and Niyamasara.[22]

Influence on Indian literature

Parts of the Sangam literature in Tamil are attributed to Jaina authors. The authenticity and interpolations are controversial, because the Sangam literature presents Hindu ideas.[23] Some scholars state that the Jain portions of the Sangam literature were added about or after the 8th-century CE, and they are not the ancient layer.[24]

Tamil Jain texts such as the Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi and Nālaṭiyār are credited to Digambara Jain authors.[25][26] These texts have seen interpolations and revisions. For example, it is generally accepted now that the Jain nun Kanti inserted a 445-verse poem into Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi in the 12th century.[27][28] The Tamil Jain literature, according to Dundas, has been "lovingly studied and commented upon for centuries by Hindus as well as Jains".[26] The themes of two of the Tamil epics, including the Silapadikkaram, have an embedded influence of Jainism.[26]

Jain scholars also contributed to Kannada literature.[29] The Digambara Jain texts in Karnataka are unusual, in that they were written under the patronage of kings and regional aristocrats. These Jain texts describe warrior violence and martial valor as equivalent to a "fully committed Jain ascetic". They thus set aside the religious premise of absolute non-violence, possibly reflecting an effort to syncretise various doctrines and beliefs found in Hinduism and Jainism.[30]

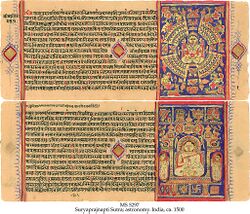

Jain manuscript libraries, called bhandaras inside Jain temples, are the oldest surviving in India.[31] Jain libraries, including the Śvētāmbara collections at Patan, Gujarat and Jaiselmer, Rajasthan, as well as the Digambara collections in Karnataka temples, have a large number of well-preserved manuscripts.[31][32] The manuscripts in the Jain libraries include Jaina literature, as well as Hindu and Buddhist texts. Almost all their texts have been dated to about, or after, the 11th century CE.[33] The largest and most valuable libraries are found in the Thar Desert, hidden in the underground vaults of Jain temples. These collections have witnessed insect damage, and only a small portion of these manuscripts have been published and studied by scholars.[33]

Notes

References

- ↑ SuryaprajnaptiSūtra , The Schoyen Collection, London/Oslo

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dundas 2002, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Dundas 2002, p. 61.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Vijay K. Jain 2016, p. xii.

- ↑ Jaini 1998, p. 78–81.

- ↑ von Glasenapp 1925, p. 124.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Dalal 2010a, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Jones & Ryan 2007, pp. 439–440.

- ↑ Dundas 2006, pp. 395–396.

- ↑ Umāsvāti 1994, p. xiii.

- ↑ Johnson 1995, pp. 46–51, 91–96.

- ↑ Finegan 1989, p. 221.

- ↑ Balcerowicz 2003, pp. 25–34.

- ↑ Chatterjee 2000, p. 282–283.

- ↑ Jaini 1991, p. 32–33.

- ↑ Cush, Robinson & York 2012, pp. 515, 839.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1992, pp. 13–16.

- ↑ Cort 1998, p. 163.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Dundas 2002, p. 116–117.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1992, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Spuler 1952, pp. 24–25, context: 22–27.

- ↑ Cort 1998, p. 164.

- ↑ Dundas 2002, pp. 118–120.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Dundas 2002, p. 83.

- ↑ Guy, John (January 2012), "Jain Manuscript Painting", The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Heilburnn Timeline of Art History), http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/jaim/hd_jaim.htm, retrieved 25 April 2013

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Dundas 2002, pp. 83–84.

Sources

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1925), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Shridhar B. Shrotri (trans.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (Reprint: 1999), ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=WzEzXDk0v6sC

- Dundas, Paul (2002), The Jains (Second ed.), London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-26605-5, https://books.google.com/books?id=X8iAAgAAQBAJ

- Jain, Vijay K. (2016), Ācārya Samantabhadra's Ratnakarandaka-śrāvakācāra: The Jewel-casket of Householder's Conduct, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-9-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=87AnDAAAQBAJ, "

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain."

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain." - Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979], The Jaina Path of Purification, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1578-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=wE6v6ahxHi8C

- Dalal, Roshen (2010) [2006], The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin books, ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=pNmfdAKFpkQC

- Chatterjee, Asim Kumar (2000), A Comprehensive History of Jainism: From the Earliest Beginnings to AD 1000, Munshiram Manoharlal, ISBN 978-81-215-0931-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=IH7XAAAAMAAJ

- Spuler, Bertold (1952), Handbook of Oriental Studies, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-04190-5, https://books.google.com/books?id=Kx4uqyts2t4C

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1992), Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-90-04-09365-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=qAPtq49DZfoC

- Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine; York, Michael (2012), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-18978-5, https://books.google.com/books?id=3N4mGlbutbgC

- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2003), Essays in Jaina Philosophy and Religion, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1977-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=NcRpfZcIhLoC

- Johnson, W.J. (1995), Harmless Souls: Karmic Bondage and Religious Change in Early Jainism with Special Reference to Umāsvāti and Kundakunda, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1309-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=vw8OUSfQbV4C

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9, https://books.google.com/books?id=OgMmceadQ3gC

- Umāsvāti, Umaswami (1994), That which is (Translator: Nathmal Tatia), Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-06-068985-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=0Rw4RwN9Q1kC

- Cort, John E., ed. (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-3785-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=yoHfm7BgqTgC

- Finegan, Jack (1989), An Archaeological History of Religions of Indian Asia, Paragon House, ISBN 978-0-913729-43-4, https://books.google.com/books?id=BrDXAAAAMAAJ

- Dundas, Paul (2006), Olivelle, Patrick, ed., Between the Empires : Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=efaOR_-YsIcC

See also

- Agama (Hinduism)

- Āgama (Buddhism)