Biology:Therosaurus

| Therosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

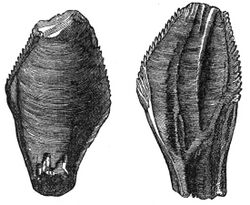

| Replica of one of the original teeth | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Clade: | †Iguanodontia |

| Genus: | †Therosaurus Fitzinger, 1840 |

| Type species | |

| †Iguanodon anglicus Holl, 1829

| |

| Species | |

|

†Therosaurus anglicus (Holl, 1829) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Iguanodon anglicus Holl, 1829 | |

Therosaurus is a genus of ornithopod dinosaurs containing the single species Therosaurus anglicus, previously known as Iguanodon anglicus. Though important in the history of paleontology as being among the first dinosaur fossils ever named and described, because the species name Iguanodon anglicus was based on very fragmentary fossil remains (a collection of teeth), the name Iguanodon was later officially transferred to a different animal. This left Therosaurus (Ancient Greek: θήρα 'thera', hunting of wild beasts;[1] Latin: anglicus, English) as the oldest available genus name for the genus containing historic but dubious teeth first discovered by Gideon Mantell in England .

History

The discovery of these teeth has long been accompanied by a popular legend. The story goes that Gideon Mantell's wife, Mary Ann, discovered the teeth[2] of an "Iguanodon" in the strata of Tilgate Forest in Whitemans Green, Cuckfield, Sussex, England , in 1822 while her husband was visiting a patient. However, there is no evidence that Mantell took his wife with him while seeing patients. Furthermore, he admitted in 1851 that he himself had found the teeth.[3] Not everyone agrees that the story is false, though.[4] It is known from his notebooks that Mantell first acquired large fossil bones from the quarry at Whitemans Green in 1820. Because also theropod teeth were found, thus belonging to carnivores, he at first interpreted these bones, which he tried to combine into a partial skeleton, as those of a giant crocodile. In 1821 Mantell mentioned the find of herbivorous teeth and began to consider the possibility that a large herbivorous reptile was present in the strata. However, in his 1822 publication Fossils of the South Downs he as yet did not dare to suggest a connection between the teeth and his very incomplete skeleton, presuming that his finds presented two large forms, one carnivorous ("an animal of the Lizard Tribe of enormous magnitude"), the other herbivorous. In May 1822 he first presented the herbivorous teeth to the Geological Society of London but the members, among them William Buckland, dismissed them as fish teeth or the incisors of a rhinoceros from a Tertiary stratum. On 23 June 1823 Charles Lyell showed some to Georges Cuvier, during a soiree in Paris, but the famous French naturalist at once dismissed them as those of a rhinoceros. Though the very next day Cuvier retracted, Lyell reported only the dismissal to Mantell, who became rather diffident about the issue. In 1824 Buckland described Megalosaurus and was on that occasion invited to visit Mantell's collection. Seeing the bones on 6 March he agreed that these were of some giant saurian — though still denying it was a herbivore. Emboldened nevertheless, Mantell again sent some teeth to Cuvier, who answered on 22 June 1824 that he had determined that they were reptilian and quite possibly belonged to a giant herbivore. In a new edition that year of his Recherches sur les Ossemens Fossiles Cuvier admitted his earlier mistake, leading to an immediate acceptance of Mantell, and his new saurian, in scientific circles. Mantell tried to corroborate his theory further by finding a modern-day parallel among extant reptiles.[5] In September 1824 he visited the Royal College of Surgeons but at first failed to find comparable teeth. However, assistant-curator Samuel Stutchbury recognised that they resembled those of an iguana he had recently prepared, albeit twenty times longer. Mantell did not describe his findings until 10 February 1825, when he presented a paper on the remains to the Royal Society of London.[3][6]

In recognition of the resemblance of the teeth to those of the iguana, Mantell named his new genus Iguanodon or "iguana-tooth", from iguana and the Greek word ὀδών (odon, odontos or "tooth").[7] Based on isometric scaling, he estimated that the creature might have been up to 18 metres (60 ft) long, more than the 12 metres (40 ft) length of Megalosaurus.[6] His initial idea for a name was Iguana-saurus ("Iguana lizard"), but his friend William Daniel Conybeare suggested that that name was more applicable to the iguana itself, so a better name would be Iguanoides ("Iguana-like") or Iguanodon.[5][8] He neglected to add a specific name to form a proper binomial, so one was supplied in 1829 by Friedrich Holl: I. anglicum, which was later amended to I. anglicus.[9]

A more complete specimen of a similar animal was discovered in a quarry in Maidstone, Kent, in 1834 (lower Lower Greensand Formation), which Mantell soon acquired. He identified it as another Iguanodon due to the resemblance in the teeth. This specimen was made the holotype of a separate species, Mantellodon carpenteri, by Paul (2012).[10]

Because Iguanodon was one of the first dinosaur genera to have been named, numerous species and specimens were assigned to it over the years, and most were later recognized as distinct genera. While never becoming the wastebasket taxon several other early genera of dinosaurs became (such as Megalosaurus and Pelorosaurus), Iguanodon has had a complicated history, and its taxonomy continues to undergo revisions.[11][12][13][14] Remains of the only well-supported species are known definitively only from Belgium, though additional remains sometimes still attributed to I bernissartensis have been found in England . However, some researchers have recommended limiting use of I. bernissartensis to the Bernissart finds, and using I. sp. (meaning undetermined species) for robust iguanodontian remains from Barremian-age rocks of Europe.[12] Thus, after thorough restudy and the transferring of the name from Mantell's teeth to the Belgian skeletons, what had once been seen as a quintessentially British dinosaur is in fact not known from England.

I. anglicus was the original type species of Iguanodon, but the holotype was based on a single tooth and only partial remains of the species have been recovered since. In March 2000, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature changed the type species to the much better known I. bernissartensis, with the new holotype being IRSNB 1534. The original Iguanodon tooth is held at Te Papa Tongarewa, the national museum of New Zealand in Wellington, although it is not on display. The fossil arrived in New Zealand following the move of Gideon Mantell's son Walter there; after the elder Mantell's death, his fossils went to Walter.[15]

References

- ↑ Liddell & Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, 1940.

- ↑ Fossil Iguanodon Tooth – Collections Online – Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Sues, Hans-Dieter (1997). "European Dinosaur Hunters". in James Orville Farlow. The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-253-33349-0.

- ↑ Lucas, Spencer G.; Dean, Dennis R. (December 1999). "Book review: Gideon Mantell and the discovery of dinosaurs". PALAIOS 14 (6): 601–602. doi:10.2307/3515316. ISSN 0883-1351.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cadbury, D. (2000). The Dinosaur Hunters. Fourth Estate:London, 384 p. ISBN:1-85702-959-3.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mantell, Gideon A. (1825). "Notice on the Iguanodon, a newly discovered fossil reptile, from the sandstone of Tilgate forest, in Sussex". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 115: 179–186. doi:10.1098/rstl.1825.0010. ISSN 0261-0523.

- ↑ Naish, Darren; David M. Martill (2001). "Ornithopod dinosaurs". Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. London: The Palaeontological Association. pp. 60–132. ISBN 0-901702-72-2.

- ↑ Olshevsky, G. "Re: Hello and a question about Iguanodon mantelli (long)". http://dml.cmnh.org/1997Aug/msg00339.html. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ↑ Holl, Friedrich (1829). Handbuch der Petrifaktenkunde, Vol. I. Ouedlinberg. Dresden: P.G. Hilscher. OCLC 7188887.

- ↑ Paul, G.S. (2012). "Notes on the rising diversity of Iguanodont taxa, and Iguanodonts named after Darwin, Huxley, and evolutionary science." Actas de V Jornadas Internacionales sobre Paleontología de Dinosaurios y su Entorno, Salas de los Infantes, Burgos. p123-133.

- ↑ Paul, Gregory S. (2007). "Turning the old into the new: a separate genus for the gracile iguanodont from the Wealden of England". in Kenneth Carpenter. Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 69–77. ISBN 0-253-34817-X.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Paul, Gregory S. (2008). "A revised taxonomy of the iguanodont dinosaur genera and species". Cretaceous Research 29 (2): 192–216. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2007.04.009.

- ↑ Norman, David B. (January 1998). "On Asian ornithopods (Dinosauria, Ornithischia). 3. A new species of iguanodontid dinosaur". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 122 (1–2): 291–348. doi:10.1006/zjls.1997.0122.

- ↑ Norman, David B.; Barrett, Paul M. (2002). "Ornithischian dinosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous (Berriasian) of England". in Milner, Andrew. Life and Environments in Purbeck Times. Special Papers in Palaeontology 68. London: Palaeontological Association. pp. 161–189. ISBN 0-901702-73-0.

- ↑ Royal Society of New Zealand. "Celebrating the great fossil hunters". Archived from the original on 2005-08-26. https://web.archive.org/web/20050826130408/http://www.rsnz.org/topics/biol/dna50/breakfast.php. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Therosaurus. |

Wikidata ☰ Q14920057 entry