Biology:Heloderma charlesbogerti

| Guatemalan beaded lizard[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Helodermatidae |

| Genus: | Heloderma |

| Species: | H. charlesbogerti

|

| Binomial name | |

| Heloderma charlesbogerti Campbell & Vannini, 1988

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

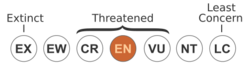

The Guatemalan beaded lizard (Heloderma charlesbogerti), also called commonly the Motagua Valley beaded lizard, is a highly endangered species of beaded lizard, a venomous lizard in the family Helodermatidae. The species is endemic to the dry forests of the Motagua Valley in southeastern Guatemala,[4] an ecoregion known as the Motagua Valley thornscrub.[5] It is the only allopatric beaded lizard species, separated from the nearest population (H. alvarezi) by 250 km (160 mi) of unsuitable habitat.[6] The Guatemalan beaded lizard is the rarest and most endangered species of beaded lizard, and it is believed that fewer than 200 individuals of this animal exist in the wild, making it one of the most endangered lizards in the world.[7] In 2007, it was transferred from Appendix II to Appendix I of CITES due to its critical conservation status.[8]

Taxonomy

The Guatemalan beaded lizard belongs to the family Helodermatidae which forms part of a clade of reptiles with toxin secreting glands.[9] This species differs from other Heloderma species in coloration and size, being the smallest one. Home ranges and behavior of these lizards were investigated using radio-telemetry at the dry forests of Zacapa, Guatemala.[10] The average home range for individuals was found to be 130 ha.[10]

This species was first discovered in 1984 by an agricultural laborer named D. Vasquez in Guatemala's Motagua Valley.[6][7]

Etymology

The generic name, Heloderma, means "studded skin", from the Ancient Greek words hêlos (ηλος), meaning "the head of a nail or stud", and derma (δερμα), meaning "skin".

The specific name, charlesbogerti, honors US herpetologist Charles Mitchill Bogert.[6][7][11]

Diet

H. charlesbogerti dwells in arroyos characterized by high densities of bird nests of doves and parakeets, whose eggs form the primary component of its diet.[12] These birds nest closer to the ground in these arroyos in trees with branches thick enough to support the weight of this heavy-bodied lizard.[12] It is known to prey upon insects, such as beetles and crickets.[10] The eggs of the Guatemalan Spiny-tailed Iguana (Ctenosaura palearis), an endangered species endemic to the same region, are an important food source for the Guatemalan beaded lizard, thereby possibly linking the status of the two.[13]

References

- ↑ "Heloderma charlesbogerti ". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=716554.

- ↑ Ariano-Sánchez, D.; Gil-Escobedo, J. (2021). "Heloderma charlesbogerti". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T181151381A181151790. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/181151381/181151790. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ↑ Species Heloderma charlesbogerti at The Reptile Database www.reptile-database.org.

- ↑ Ariano-Sánchez, Daniel; Salazar, Gilberto (2007). "Notes on the distribution of the endangered lizard, Heloderma horridum charlesbogerti, in the dry forests of eastern Guatemala: an application of multi-criteria evaluation to conservation". Iguana 14: 152-158.

- ↑ "Motagua Valley thornscrub". World Wildlife Fund. http://worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt1312.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Campbell, Jonathan A.; Vannini, Jay P. (1988). "A new subspecies of beaded lizard, Heloderma horridum, from the Motagua Valley of Guatemala". Journal of Herpetology 22 (4): 457–468. doi:10.2307/1564340.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Beck, Daniel D. (2005). Biology of Gila Monsters and Beaded Lizards (Organisms and Environments). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 247. ISBN 0-520-24357-9.

- ↑ Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. 2007. Resume of the 14th Convention of the Parts. The Hague. The Netherlands.

- ↑ Ariano-Sánchez D (2008). "Envenomation by a wild Guatemalan beaded lizard Heloderma horridum charlesbogerti ". Clinical toxicology 46 (9): 897-899.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Ariano-Sánchez D (2006). "The Guatemalan beaded lizard: endangered inhabitant of a unique ecosystem". Iguana 13: 178-183.

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN:978-1-4214-0135-5. (Heloderma horridum charlesbogerti, p. 30).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ariano-Sánchez, Daniel (2003). "Distribución e historia natural del escorpión, Heloderma horridum charlesbogerti Campbell y Vannini, (Sauria: Helodermatidae) en Zacapa, Guatemala y caracterización de su veneno ". Guatemala: U.V.G., p. 68. (in Spanish).

- ↑ Coti, Paola; Ariano-Sánchez, Daniel (2008). "Ecology and traditional use of the Guatemalan black iguana (Ctenosaura palearis) in the dry forests of the Motagua Valley, Guatemala". Iguana 15 (3): 142–149.

Further reading

- Reiserer, Randall S.; Schuett, Gordon W.; Beck, Daniel D. (2013). "Taxonomic reassessment and conservation status of the beaded lizard, Heloderma horridum (Squamata: Helodermatidae)". Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7 (1): 74–96. (Heloderma charlesbogerti, elevated to species).

- Owens, T.C. (2006). "Ex-situ: Notes on reproduction and captive husbandry of the Guatemalan beaded lizard (Heloderma horridum charlesbogerti)". Iguana 13 (3): 212-215. https://journals.ku.edu/iguana/article/view/17628.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q1049318 entry

|