Biology:Blotchy swellshark

| Blotchy swellshark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Subdivision: | Selachimorpha |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Scyliorhinidae |

| Genus: | Cephaloscyllium |

| Species: | C. umbratile

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cephaloscyllium umbratile D. S. Jordan & Fowler, 1903

| |

| |

| Range of the blotchy swell shark[2] | |

The blotchy swellshark, or Japanese swellshark, (Cephaloscyllium umbratile) is a common species of catshark, belonging to the family Scyliorhinidae. The Blotchy swellshark is found at depths of 90–200 m (300–660 ft) in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, from Japan to Taiwan. It is benthic in nature and favors rocky reefs. Reaching 1.4 m (4.6 ft) in length, this thick-bodied shark has a broad head, large mouth, and two unequally-sized dorsal fins positioned far back past the pelvic fins. It can be identified by its dorsal coloration, consisting of seven brown "saddles" and extensive darker mottling on a light tan background. This species has often been confounded with the draughtsboard shark (C. isabellum) and the Sarawak pygmy swellshark (C. sarawakensis) in scientific literature.

Voracious and opportunistic in feeding habits, the blotchy swellshark is known to consume numerous types of fishes and invertebrates, including an unusually high diversity of cartilaginous fishes. Like other Cephaloscyllium species, it is capable of rapidly inflating its body as a defense against predators. This species is oviparous, with females laying encapsulated eggs two at a time. There is no well-defined breeding season and reproduction occurs year-round. The eggs hatch after approximately one year. The blotchy swellshark is harmless and fares well in captivity. It is caught as bycatch in commercial bottom trawls, though its population does not seem to have suffered from fishing activity.

Taxonomy

American ichthyologists David Starr Jordan and Henry Weed Fowler described the blotchy swellshark in a 1903 volume of Proceedings of the United States National Museum, based on a 98 cm (39 in) long stuffed dry skin originally obtained from Nagasaki, Japan. They gave it the specific epithet umbratile (from the Latin umbratilis, meaning "shaded") and assigned it to the genus Cephaloscyllium.[3]

The taxonomy of the blotchy swellshark has a history of confusion.[4] The holotype dried skin could not be located when shark expert Stewart Springer prepared his 1979 review of the catsharks, and in its absence he synonymized C. umbratile with C. isabellum on the basis of "inconclusive morphometric differences".[5] Some authors followed Springer's judgment while others, particularly in Japan, preferred to keep referring to C. umbratile.[6] The taxonomy of this species was further muddled by the application of the name C. umbratile to a similar but smaller species sharing part of its range. This second species, once referred to as "pseudo-umbratile" by Leonard Compagno, has since been identified as C. sarawakensis. Recently, the holotype was found again, and in 2008 Cephaloscyllium umbratile was re-described as distinct from C. isabellum by Jayna Schaaf-Da Silva and David Ebert.[4]

Distribution and habitat

The blotchy swellshark is known to inhabit the northwestern Pacific Ocean from Hokkaido, Japan southward to Taiwan, including the Yellow Sea.[7] Its range may extend as far as New Guinea.[1] This abundant species is a bottom-dweller that inhabits rocky reefs on the continental shelf, at depths of 90–200 m (300–660 ft).[6][8]

Description

The maximum reported length of the blotchy swellshark is 1.4 m (4.6 ft).[8] It has a firm, stout body with a soft, distensible abdomen, and a short, broad, flattened head. The snout is proportionately long and rounded, with large nostrils divided by short, triangular flaps of skin in front. The small, horizontally oval eyes are placed high on the head and equipped with rudimentary nictitating membranes (protective third eyelids). A tiny spiracle lies closely behind each eye. Behind the spiracle are five pairs of gill slits, which are short and become progressively smaller posteriorly. The capacious mouth forms a broad arch, and lacks furrows at the corners. The small teeth have a central cusp flanked by a smaller cusplet on both sides. There are around 59 tooth rows in the upper jaw and 62 tooth rows in the lower jaw.[4][7]

The pectoral fins are moderately large and wide, with rounded tips. The dorsal fins have rounded apexes and are placed well back on the body, the first originating behind the midpoints of the small pelvic fins. The first dorsal fin is about twice as high as the second. The anal fin is nearly as large as the first dorsal fin and placed slightly ahead of the second dorsal fin. The caudal fin is large and broad, with the upper lobe longer than the lower and bearing a prominent ventral notch near the tip. The skin is thick and sparsely covered by large, well-calcified dermal denticles; each denticle has a diamond-shaped crown with three horizontal ridges. This shark is cream-colored with dark brownish to grayish mottling on the back and sides, and seven dark brown dorsal "saddles" on the body and tail. The mottling intensifies with age, while the saddles fade and may become obscured. Older sharks may also have a dark blotch on either side between the pectoral and pelvic fins. The underside is pale, with scant darker marks.[4][7]

Biology and ecology

Like other members of its genus, when threatened the blotchy swellshark is capable of rapidly inflating its stomach with water or air. This allows the shark to wedge itself inside a rocky crevice, becoming extremely difficult to remove.[9] This species is an opportunistic, highly voracious predator; one recorded female 1 m (3.3 ft) long had 10 fish about 20 cm (7.9 in) long and 15 squid about 15 cm (5.9 in) long in her stomach. Predominantly piscivorous, this species is known to prey upon hagfish and at least 50 species of bony fishes, including fast-swimming types that inhabit open water; significant prey species include the mackerel Scomber japonicus, the sardine Sardinops melanostictus, the filefish Thamnaconus modestus, and the hakeling Physiculus japonicus. Unusually for such a small shark, it also feeds on at least 10 species of cartilaginous fishes, including lantern sharks, catsharks (particularly the cloudy catshark, Scyliorhinus torazame, and its eggs), the electric ray Narke japonica, and skates (including their eggs). It also cannibalizes smaller members of its own species. Cephalopods, mostly the squid Doryteuthis bleekeri and the cuttlefish Sepia spp., are also frequently taken, while crabs, shrimp, and isopods are occasionally consumed.[6] The dietary composition of juveniles varies notably from place to place.[10]

The blotchy swellshark is oviparous, and reproduction proceeds throughout the year with no obvious seasonal cycling. Adult females have a single functional ovary, on the right, and two functional oviducts. The species is thought to be relatively prolific, as the ovary contains numerous ova at various stages of development. Pairs of eggs are laid at a time, one per oviduct.[6] Females have been documented producing eggs even after years without male contact, suggesting that they may be able to store sperm.[11] The purse-shaped egg capsules are relatively large and thick, measuring around 12 cm (4.7 in) long and 7 cm (2.8 in) across. The capsule surface is smooth with lengthwise striations, and opaque cream in color with yellow margins. Long, coiled tendrils extend from the four corners of the capsule. When the embryo is 11 cm (4.3 in) long, the external gills have been lost, the dermal denticles have begun to develop, and light brown saddles are present.[7] The eggs take roughly one year to hatch; newly emerged sharks measure 16–22 cm (6.3–8.7 in) long.[8] From a series of captive rearing experiments, Sho Tanaka reported that hatchling sharks grew in length by up to 0.77 mm (0.03 in) per day.[12] Males and females attain sexual maturity at the size of 86–96 cm (34–38 in) and 92–104 cm (36–41 in) respectively; the growth rate after maturity is very low.[6] Known parasites of this species include the nematode Porrocaecum cephaloscyllii,[13] and the leech Stibarobdella macrothela.[14]

Human interactions

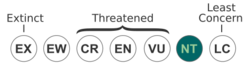

Harmless to humans, the blotchy swellshark adapts readily to captivity and has reproduced in public aquariums.[8] This species is caught incidentally by Japanese and Taiwanese bottom trawlers and brought to market. Intensive commercial fishing within its range do not yet appear to have impacted its numbers. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed it as Near Threatened.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Rigby, C.L.; Walls, R.H.L.; Derrick, D.; Dyldin, Y.V.; Herman, K.; Ishihara, H.; Jeong, C.-H.; Semba, Y. et al. (2021). "Cephaloscyllium umbratile". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T169232956A124533854. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T169232956A124533854.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/169232956/124533854. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ Compagno, L.J.V.; M. Dando; S. Fowler (2005). Sharks of the World. Princeton University Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-0-691-12072-0.

- ↑ Jordan, D.S.; H.W. Fowler (March 30, 1903). "A review of the elasmobranchiate fishes of Japan". Proceedings of the United States National Museum 26 (1324): 593–674. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.26-1324.593. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/9440.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Schaaf-Da Silva J.A.; D.A. Ebert (September 8, 2008). "A revision of the western North Pacific swellsharks, genus Cephaloscyllium Gill 1862 (Chondrichthys: Carcharhiniformes: Scyliorhinidae), including descriptions of two new species". Zootaxa 1872 (1872): 1–8. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1872.1.1.

- ↑ Springer, S. (1979). "A revision of the catsharks, Family Scyliorhinidae." NOAA Technical Report NMFS-Circ. 422: 1–152.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Taniuchi, T. (1988). "Aspects of reproduction and food habits of the Japanese swellshark Cephaloscyllium umbratile from Choshi, Japan". Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Scientific Fisheries 54 (4): 627–633. doi:10.2331/suisan.54.627.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Nakaya, K. (1975). "Taxonomy, comparative anatomy and phylogeny of Japanese catsharks, Scyliorhinidae". Memoirs of the Faculty of Fisheries, Hokkaido University 23: 1–94. http://eprints.lib.hokudai.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2115/21861/1/23(1)_P1-94.pdf.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Michael, S.W. (1993). Reef Sharks & Rays of the World. Sea Challengers. p. 53. ISBN 0-930118-18-9.

- ↑ Hennemann, R.F. (2001). Sharks & Rays: Elasmobranch Guide of the World. IKAN-Unterwasserarchiv. p. 103.

- ↑ Horie, T.; S. Tanaka (2002). "Reproduction and food habits of the Japanese swellshark, Cephaloscyllium umbratile (family Scyliorhinidae) in Suruga Bay, Japan". Journal of the School of Marine Science and Technology, Tokai University 53: 89–109.

- ↑ Masuda, M.; S. Kametsuta; M. Teshima (1992). "Female swell sharks (Cephaloscyllium umbratile) producing fertile eggs after a long separation from male sharks". Journal of Japanese Association of Zoological Gardens and Aquariums 34 (1): 1–3.

- ↑ Tanaka, S. (1990). "Age and growth studies on the calcified structures of newborn sharks in laboratory aquaria using tetracycline." NOAA Technical Report NMFS 90: 189–202.

- ↑ Yamaguti, S. (1941). "Studies on the helminth fauna of Japan. 33. Nematodes of fishes, II". Japanese Journal of Zoology 9 (3): 343–396. doi:10.1017/s0022149x00017788. PMID 13787117.

- ↑ Yamauchi, T.; Y. Ota; K. Nagasawa (August 20, 2008). "Stibarobdella macrothela (Annelida, Hirudinida, Piscicolidae) from elasmobranchs in Japanese waters, with new host records". Biogeography 10: 53–57.

Wikidata ☰ Q1949737 entry

|